Read enough children’s literature and you’ll be left in no doubt: The city is bad for children. Take them out to the country, which is utopian, pristine and a veritable fantasy landscape.

There was once an old woman who left the city to get away from all the noise and confusion. Out in the country she found a small house by a creek with a big shade tree in the back yard.

Duck Cakes For Sale, 1989

This ideology is a specifically white ideology (the ideology of publishing and children’s books):

White people love to be outside. But not everyone knows that another thing they like to do is make people feel bad for wanting to watch sports on TV or play video games. While it would be easy to get angry at white people for this, remember it is hard wired in their head that the greatest thing a person can do in their free time is to hike/walk/bike outdoors.

Stuff White People Like: Making you feel bad about not going outside

WHAT DOES THE CITY REPRESENT?

Naomi Hamer sums it up like this:

New York City. Los Angeles. London. Paris. Toronto. Distinct experiences of urban life in major European and North American cities have inspired countless works of literature, film, and art, as well as, musical compositions and television programs for both children and adults. Diverse images of “the city” in art and literature offer a range of literal and metaphoric implications: the city as metaphor for modernization;

- the Old World European city as romantic or nostalgic setting

- the futuristic city as cautionary comment on technology

- the city as centre of consumer and corporate culture

- the city as a symbol of anonymous and empty (post)modern life

- the city as emblem of the disrupted relationship between humans and nature

- the city as a site for criminalization, drug use, prostitution, gang violence and poverty.

In the context of this artistic and literary commentary over the last century, the image of the city has also become an integral and dynamic element in children’s literature.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF CITIES

Do you live in a small town? I do. Ours numbers about 17,000 people. We think of it as a small country area, but that was more than enough to comprise a ‘provincial centre’ in the 1700s.

By 1700, urban areas with five thousand or more persons comprised some 15 percent of England’s population of five million inhabitants, a proportion slightly above the norm for Western Europe as a whole. The country’s metropolis, London, boasted a citizenry of 575,000 dwarfing provincial centres with between twelve and thirty thousand inhabitants apiece. By then, large-scale urbanization had already transformed much of continental Europe, from the Italian peninsula to southern Scandinavia. Most cities and towns resembled a rabbit warren of narrow streets and alleys — cramped, crooked, and dark. Upper facades, by projecting over streets below, obstructed light from both sun and moon. Already by the 1600s, buildings in Amsterdam towered four stories high. Not until the eighteenth century would linear thoroughfares of ample breadth set the standard in urban design.

A. Roger Ekirch, At Day’s Close

TOWN/COUNTRY SYMBOLISM IN LITERATURE

COUNTRY = NATURAL, CITY = NOISE

[The] symbolic significance of the city is better understood in contrast with the “non-city” which surrounds it. The city versus nature contrast is one of the major symbolic contrasts in story forms for the city is the greatest overall symbol of mankind. Raymond Williams in The Country And The City notes that the country offers “the idea of a natural way of life: of peace, innocence, and simple virtue.” On the other hand, the city:

“…has gathered the idea of an achieved centre: of learning, communication, light. Powerful hostile associations have also developed: on the city as a place of noise, worldliness and ambition: on the country as a place of backwardness, ignorance and limitation. A contrast between country and city, as fundamental ways of life, reaches back into classical times.”

Symbolism of Place

Many 20th century children’s books are written with the ideology that children should be outside, self-governed, exploring, free and unencumbered by the rules of the city. Sometimes when I’m reading classic children’s books I hear the voice of my seventy-something-year-old friend, and I wonder what Edith Nesbit and Enid Blyton would say if they saw the way children are playing together today?

Eva Ibbotson was aware of this well-understood dichotomy evident throughout British children’s literature in particular. In her middle grade novel The Beasts of Clawstone Castle, the adventures begin when two children are sent from a nice part of London to stay for the summer in a castle in the country. The parents decide to go to America, but there’s that pesky matter of the children:

“We can’t possibly leave them,” said Mr Hamilton.

“And we can’t possibly take them along,” said Mrs Hamilton.

“So we’ll have to refuse.”

“Yes.”

But the Americans had offered a lot of money and the car was making terrible noises and bills were dropping through the letter box in droves.

“Unless we send them to the country. They ought to be in the country,” said Mrs Hamilton. “It’s where children ought to be.“

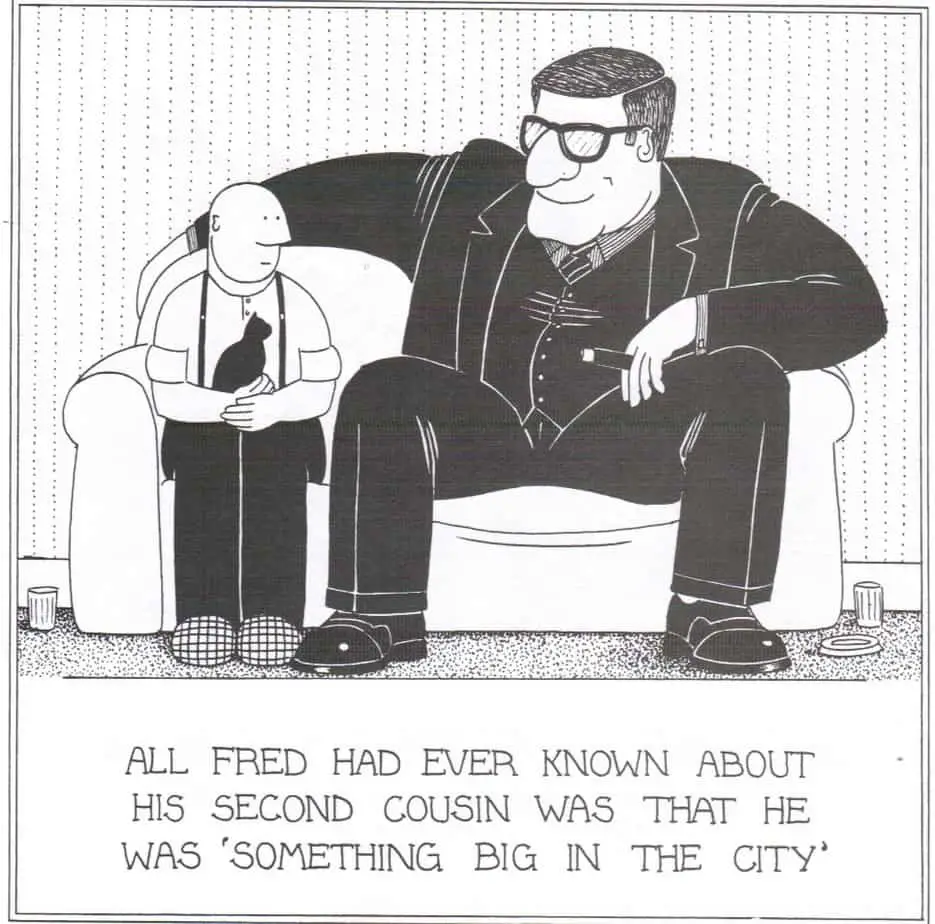

Cities themselves have a public relations problem in children’s literature. In adolescent fantasy the city often symbolises a threat. The city is the dangerous world of adults, who often succumb to temptation in cities. Often, the city is symbolically equivalent to an ocean, where inhabitants are under constant threat from bigger creatures.

IDEOLOGY OF COUNTRY GOODNESS IN THE FIRST AND SECOND GOLDEN AGES OF CHILDREN’S LITERATURE

“There’s naught as nice as th’ smell o’ good clean earth, except th’ smell o’ fresh growin’ things when th’ rain falls on ’em.”

The Secret Garden, Frances Hodgson Burnett

Let’s take a look at what the septuagenarians in our lives were reading as children, and again, no doubt, to their own children. Is this ‘country kids are superior to urban kids’ ideology seen in children’s books published today?

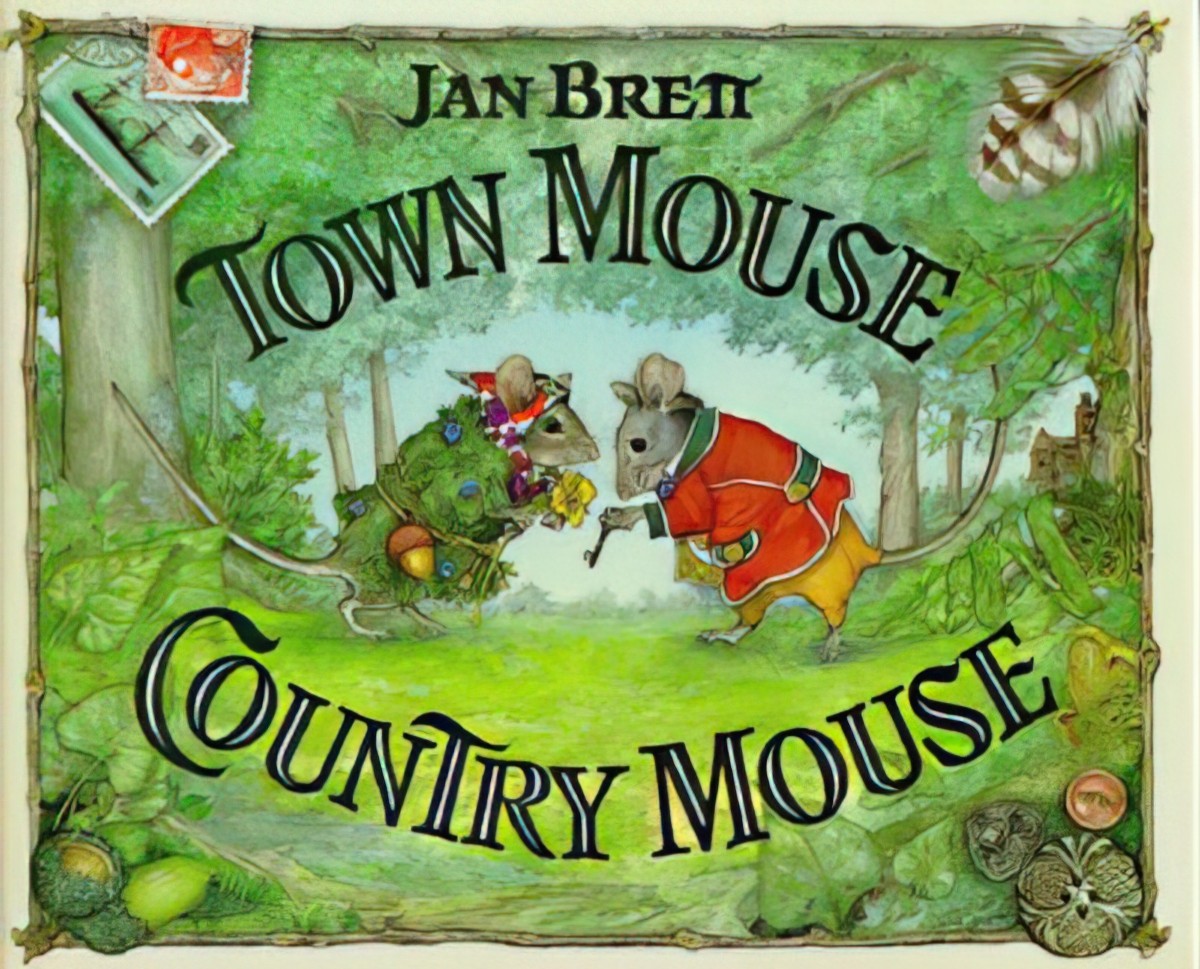

What did Aesop think of the town versus country? Here’s the thing about Aesop’s fables, which applies equally to religious texts: The reader brings their own values to the text rather than the other way around. Each age of readers has interpreted these fables according to their own existing worldview.

Was Aesop criticising sophisticated city folk, or did he just happen to situate the proud mouse in the town, and the humble mouse in the country?

Aesop’s Fables are still published today as picture books for children — often cheaply produced.

BEATRIX POTTER

Johnny Town-Mouse is Beatrix Potter’s retelling of the Aesop Fable. Potter wrote this story in a scramble as she was busy dealing with jobs on her new farm. Her publisher was telling her to provide them with a new story.

Despite the utter busyness involved in farm life, it’s clear from a cursory glance at Potter’s illustrations which of the two environments she preferred. Her censure of town mice (children) is clear from the dialogue below:

Timmy Willie longed to be at home in his peaceful nest in a sunny bank. The food disagreed with him; the noise prevented him from sleeping. In a few days he grew so thin that Johnny Town-mouse noticed it, and questioned him. He listened to Timmy Willie’s story and inquired about the garden. “It sounds rather a dull place? What do you do when it rains?”

EDITH NESBIT

E. Nesbit was particularly clear on her views of child-rearing in London:

London is like prison for children, especially if their relations are not rich.

Of course there are the shops and the theatres, and Maskelyne and Cook’s, and things, but if your people are rather poor you don’t get taken to the theatres, and you can’t buy things out of the shops; and London has none of those nice things that children may play with without hurting the things or themselves – such as trees and sand and woods and waters. And nearly everything in London is the wrong sort of shape – all straight lines and flat streets, instead of being all sorts of odd shapes, like things are in the country. Trees are all different, as you know, and I am sure some tiresome person must have told you that there are no two blades of grass exactly alike. But in streets, where the blades of grass don’t grow, everything is like everything else. This is why so many children who live in towns are so extremely naughty. They do not know what is the matter with them, and no more do their fathers and mothers, aunts, uncles, cousins, tutors, governesses, and nurses; but I know. And so do you now. Children in the country are naughty sometimes, too, but that is for quite different reasons.

Five Children and It

In the Edwardian era it was thought not only that the countryside itself was better, but also that people who came from the country were better… at least, if you needed their services as staff:

Children, particularly girls, also made up a significant proportion of the lower posts in a large household and the higher up the social scale the employer, the more cachet was awarded to the positions in the house. Young girls would be looking for a post in a good home from the age of twelve or thirteen, and in some cases they started as young as ten. And while many of these came from the city slums, employers often preferred to take the children of rural families, who were considered to be more conscientious and hard-working than those from the cities.

Life Below Stairs: True Lives of Edwardian Servants by Alison Maloney

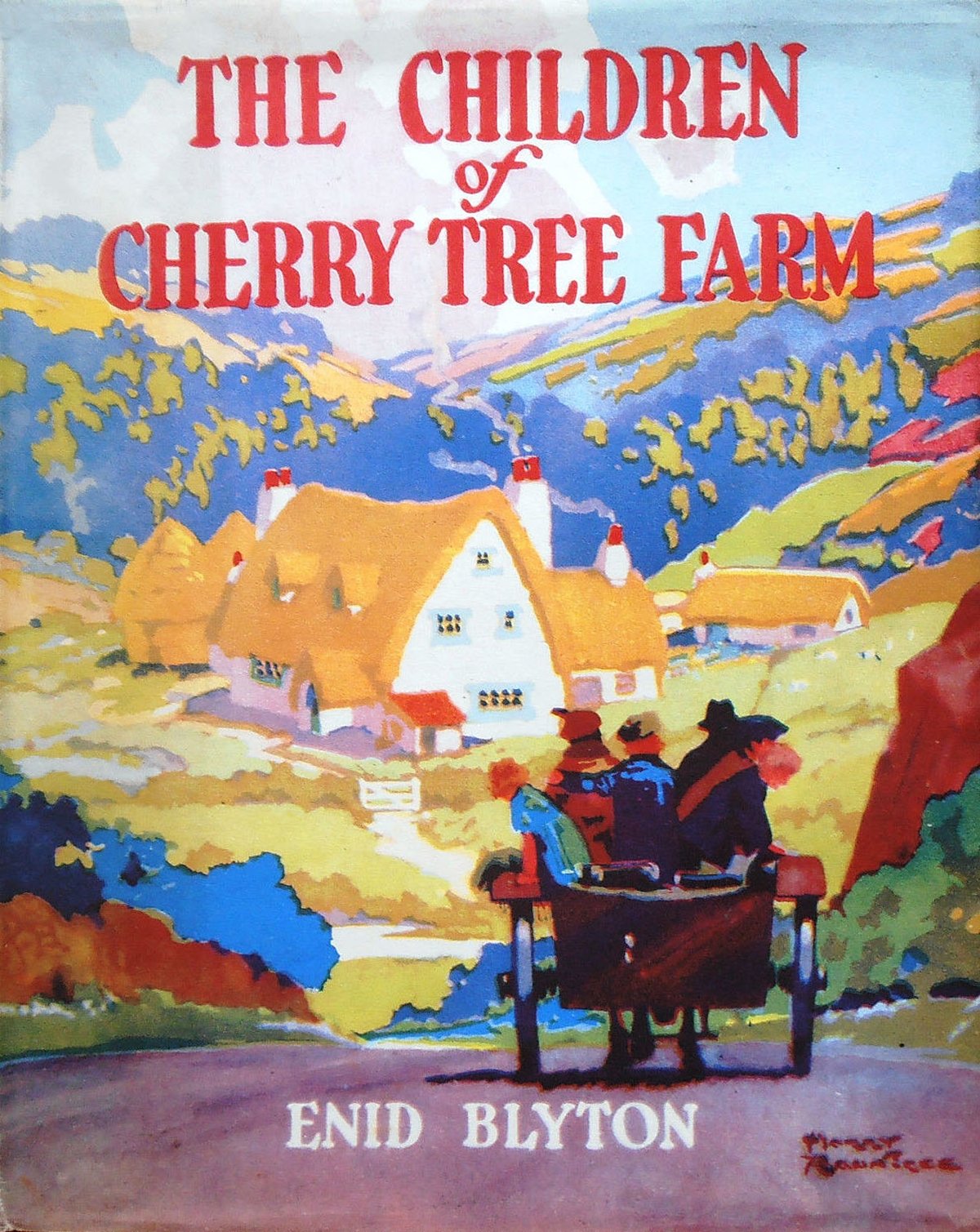

ENID BLYTON

Enid Blyton was another author of the view that country kids are wholesome whereas city kids are corrupt. At the beginning of The Enchanted Wood, Jo, Bessie and Fanny move from the city to the country, where they are immediately absorbed and influenced by the natural landscape. In the later books they are visited first by Dick and next by Connie. Both of these children, being from the city, are therefore separate from the landscape and problematic. Blyton is particularly harsh on Connie, and punishes the character for her interest in pretty clothes by covering her in water out of Dame Wash-a-lot’s soapy old washing water. Country kids — pure and unadulterated — do not care about their clothes, wearing them only for practical reasons.

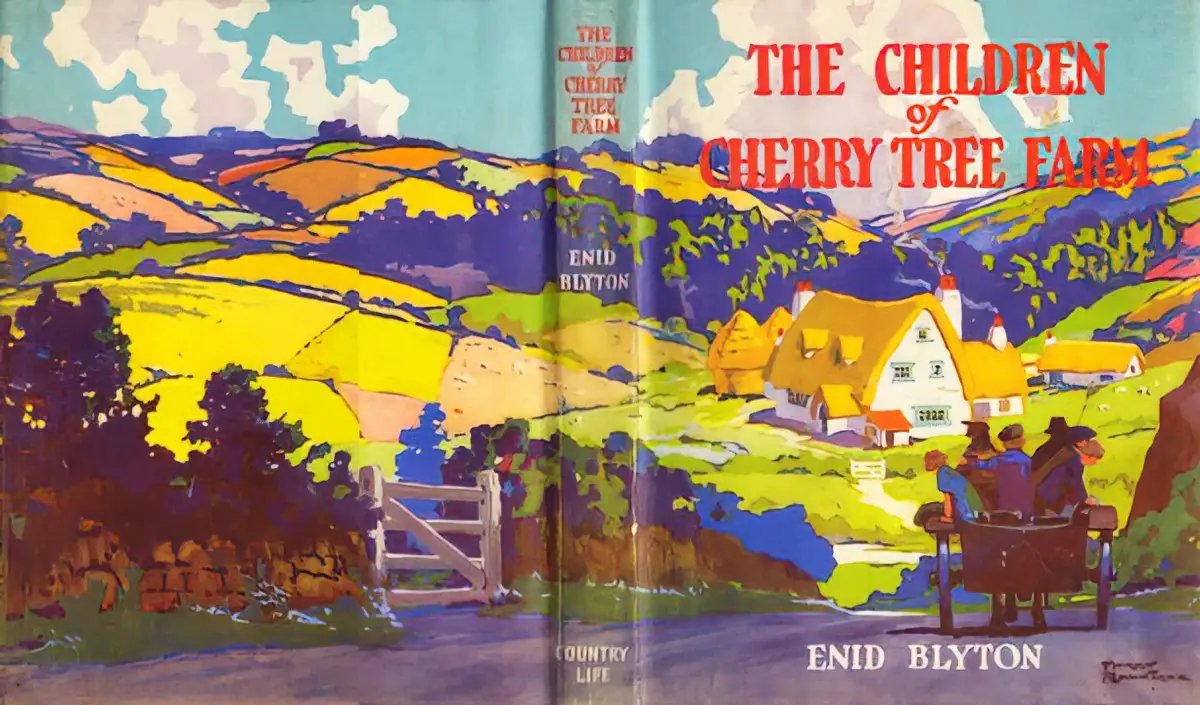

Blyton’s love of the country comes through most clearly in her Cherry Tree Farm books, in which children from the city have their lives dramatically improved after moving to an idyllic farm of the kind you’re likely to see on margarine lids. I absolutely loved this idyll as a child reader.

COUNTRY VS TOWN IN MODERN CHILDREN’S LITERATURE

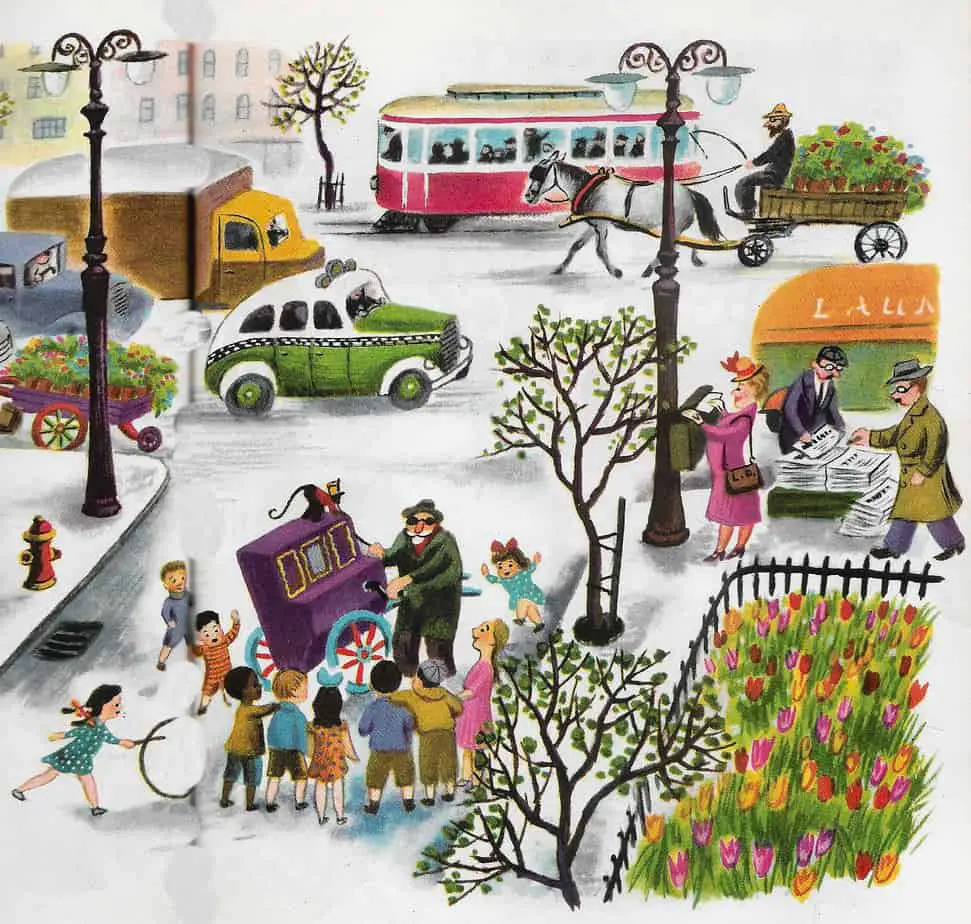

Many historical and contemporary classics of children’s literature rely on an escape from the city in order for protagonists to experience an alternate fantasy or natural world; however, increasingly in modern children’s novels and picture books, the city itself has innately magical and fantastical qualities or becomes the site for a (quasi)-fantastical realm. Mary Beaty remarks in her reflection on the child protagonists of Manhattan: “urban children somehow form private lives in the midst of the moil of policemen, tradesmen, traffic and trams” … Rather than running away to a natural realm, child protagonists in these texts exist within their own imaginative spheres in the core of the city where they live and play. In their depiction of these imaginative spheres, many of these novels and picture books exemplify an enchanted or magic realism in their child’s-eye-view perspectives of the city.

Naomi Hamer

As noted above, in modern children’s literature you won’t easily find the clearcut disparaging of the city.

A problem faced by children’s authors writing in a modern setting is that there is little legitimate room for adventure. One solution is to take the children into ‘the wild’, where they can undergo the requisite maturity without the interference of adults.

On the other hand, the city itself can be turned into a symbolic wilderness, and there’s nothing stopping modern authors from doing just that. Cities, after all, can be just as terrifying as jungles and forests.

- Spider-man (New York) and other superhero stories such as Jessica Jones and Batman

- Fish Tank (Essex)

- Blade Runner (L.A.)

Or cities can be symbolic forests:

- Ghostbusters

- Harriet The Spy

Wolf Hollow by Lauren Wolk recaptures something of the country/city divide. Set in West Pennsylvania in 1043, a city girl arrives from the country. This girl is more sophisticated and meaner than the country kids, who have only just got electricity, for instance. Living in a small town, Annabelle — the main character — must learn some city-like sophistication. She must learn to lie.

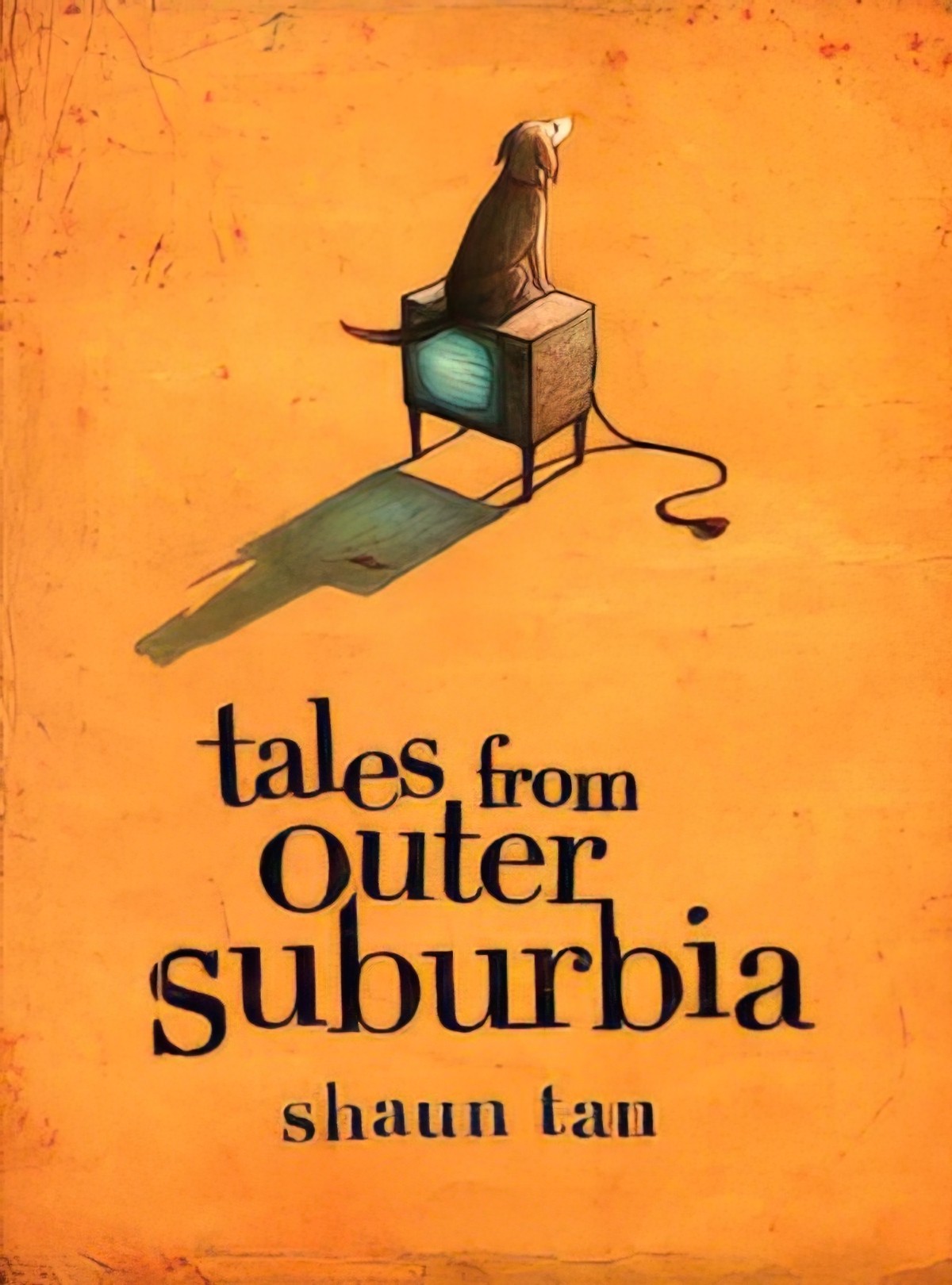

Don’t forget, too, that the suburbs can just as terrifying, especially as they are ‘snail under the leaf settings‘, rotten just beneath the surface.

In picture books for younger readers we have examples such as Olivia by Ian Falconer. Olivia lives in New York, which you might expect to be a stifling place for children, and I’m sure it can be if money is tight. But Olivia is taken out to museums and ballet performances as well as to parks and to the seaside. It’s hard to argue that city kid Olivia is at all psychologically bereft for having been brought up in the city.

You’ll still find plenty of ‘storybook farms‘, but these exist alongside more realistic depictions of rural life, such as the Australian picture book Two Summers, which is about drought.

THE COUNTRY CITY DIVIDE IN STORIES FOR ADULTS

The spatial visualization of disaster, as it is found in representations of the apocalypse, seems to offer a kind of overbearing presence — or what Vivian Sobchack called the ‘concrete “loftiness”‘. The cinematic framing of destruction not only turns it into a strange spectacle, but also provides the onlooker with a rearrangement of a spatial and temporal order, as it engages with and comments on the apocalypse’s effects on social formations such as the family or the community. Working as vehicles of violating or subverting a specific social order, representations of the post-apocalypse usually rely on settings that are increasingly depicted as abandoned, fragmented or disintegrated, at the same time highlighting the idea that they are products of their respective historical context. This is also reflected in the popularity of survivalist themes or lifestyles which have seen a revival in the form of US shows such as Doomsday Preppers (2011-4) or the British documentary Preppers UK 2 (2013), which introduced the audience to images of burning buildings and police vans from the London riots of 2011. Both series conceived an image of the city as a problem-ridden space that needed to be avoided, which is why escaping from the cities to the empty countryside was repeatedly presented as a major objective.

“Empty spaces: perspectives on emptiness in modern history”, Martin Walter, University of London Press, 2019

In post-apocalyptic settings, the city may be terrible but the rural areas are often no better.

while empty cities are usually perceived as dangerous, the symbolism of an empty countryside is juxtaposed onto the anxieties and fears of urban settlements. … the emptiness of the surrounding countryside and the journeying motif function at least as elements of short-term relief and tranquillity, while the empty road is not exclusively symbolic of post-apocalyptic displacement but may also signify a path to a new and safe future.

“Empty spaces: perspectives on emptiness in modern history”, Martin Walter, University of London Press, 2019

Interestingly, the message about the country is often the direct opposite in stories for adults. Take the 2016 indie American film Little Boxes starring Melanie Lynskey and Nelsan Ellis. This is an academic, woke, left-leaning couple who move from New York to a small, predominantly white town in Washington State when Lynskey’s character achieves tenure as a professor at the local university. They make quite a few social mistakes, highlighting the small-town insecurities of the people who live there. Overall, the message is that small town folk are equally small-minded.

Amanda Craig makes a comment on the English country/city divide when speaking of her novel The Lie Of The Land:

The divorcing couple in your new novel move to Devon together because they can’t afford to buy separate homes in London. Where did that idea come from?

My husband and I bought this bolthole in Devon and it was a revelation. As a result, this book is absolutely not about people moving to the country and having a lovely time. It’s about the difficult aspects of living in the countryside as well as its beauty, and how it’s really not helped by the metropolitan elite.In the novel’s tension between city and country, your heart seems to be with the countryside…

My heart is perpetually divided between the two. I still live in London and I completely rejoice in its energy and multiculturalism and optimism, but I think there’s this community – many of them the people who stunned half the electorate by voting for Brexit – who are very angry. They’re people who are not racist, they’re not stupid. They’re good people and they have justifiable complaints that have not been listened to.Do you think Londoners are out of touch with the rest of the country?

The Guardian

I think some Londoners view the countryside as a kind of toytown. There’s this fantasy that everything’s incredibly pretty and it’s not a place where people do serious work, and this could not be further from the truth. They’re real people with real problems and real talents and they’re utterly neglected by the powerbrokers in the capital.

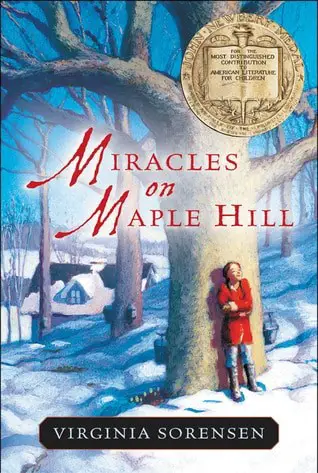

Miracles On Maple Hill (1956)

Marly and her family share many adventures when they move from the city to a farmhouse on Maple Hill. Her father is recovering from being a prisoner-of-war. The small town and the varied happenings and activities of country life help them to recover from past unhappiness, and bond more closely as a family.

RELATED

- Why The Places We Live Make Us Happy from The Atlantic

- Watch The World’s Urban Population As It Balloons from co.Exist

- And this is why I’m glad I don’t live in a city anymore: Stay Off The Pole and other annoyances, from Feministe

- Why The Places We Live Make Us Happy from The Atlantic Cities

- Study Links Quality Urbanism To Happiness from Streets Blog Network

- Leo Hollis’s top 10 books about cities from The Guardian

- Future Starts Slow: a photographic project documenting cities as places of alienation and isolation, distancing humans from their true nature and origins.

- Is Urban Living Actually Better than Suburban Living? from GOOD

- How City Living Is Reshaping the Brains and Behavior of Urban Animals from Wired

RELATED TERMS

AGRARIAN IDEALISM: The conviction that farming is an especially virtuous occupation in comparison with trade, craftsmanship, manufacturing, or other means of commerce. Romans like Hesiod and Virgil, for instance, praised the simple, hard-working ethics of the Roman farmer. (See the Eclogues for an example.) Jefferson dreamed of a future America composed primarily of gentlemen-farmers who lived off the fruits of their plantations without the need for outside trade in his Queries. The agrarian ideal manifested equally strong in Romantic writings as one form of the American Dream motif.

Literary Terms and Definitions

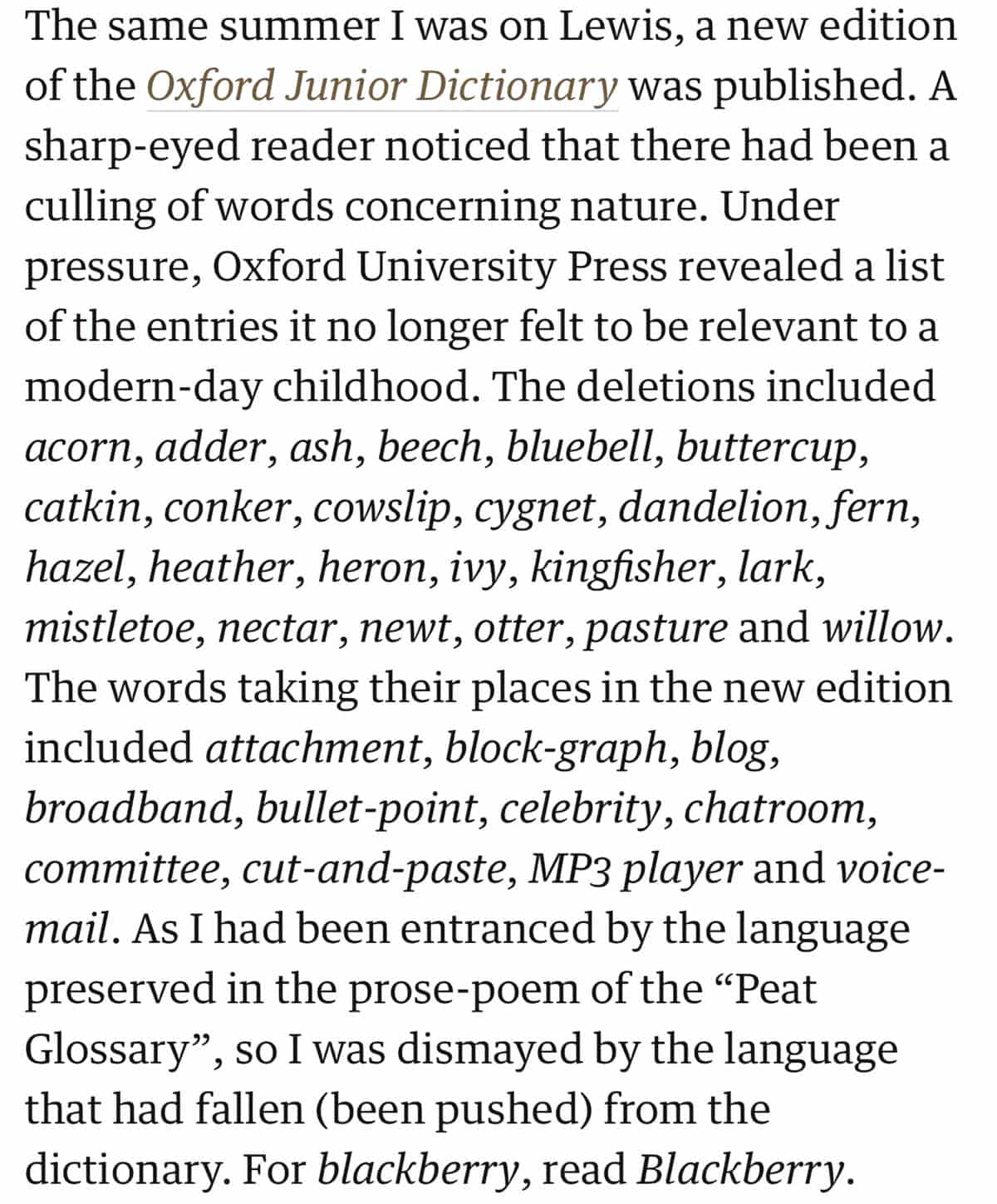

Nature is disappearing from kids’ books

Header photo by Ludomił