The Cider Duck (1969) is an Australian picture book written by Joan Woodberry and illustrated by Molly Stephens.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR AND ILLUSTRATOR

Joan Woodberry (1921-2010) was an influential, widely-travelled Tasmanian feminist whose efforts made women’s lives palpably better in Tasmania.

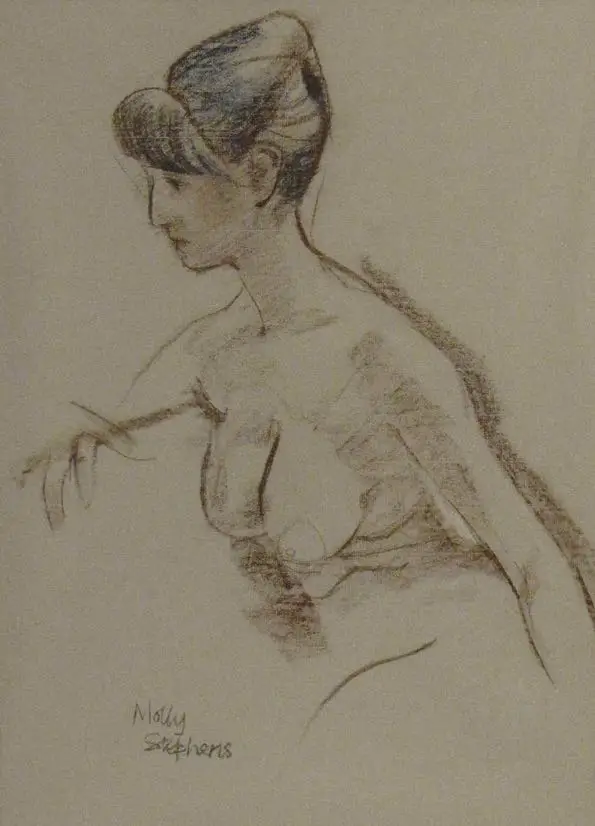

Finding information on Molly Stephens is a little more difficult partly because she was also known as Molly Pascall, her birth name. The Cider Duck is perhaps the only published book she illustrated. It seems she was a fine artist and teacher the rest of the time. She may have liked cats? If it’s the same Molly Stephens, she left some of her estate to The Melbourne Symphony Orchestra. Like Joan, Molly was a teacher. She was born in 1920 and educated in England, as an artist, then after the war spent a while in Egypt. She then emigrated to Australia. She lived in Tasmania until her death in 1970, first in Smithton, then in Hobart. She specialised in portraits.

In short, both writer and illustrator were well-travelled women who lived through the 20th century wars. They both worked with children and settled in Tasmania. I’m guessing — though it’s just a guess — they knew each other and collaborated, unlike most writer/illustrator combos today, who are set up by the publisher and rarely meet until the job is done, if at all.

STORYWORLD OF THE CIDER DUCK

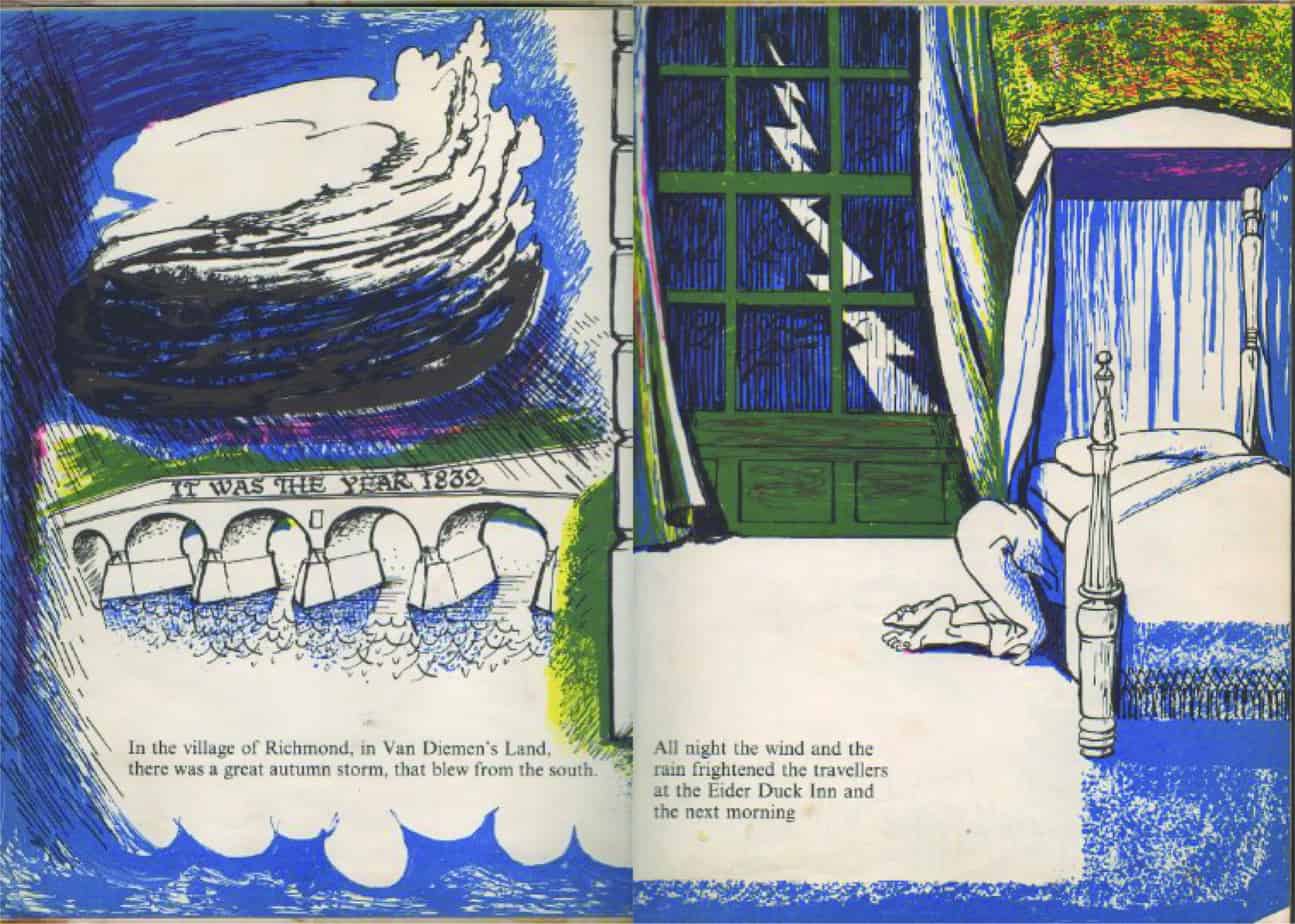

The reader is left in no doubt about the setting:

- When? 1832, conveyed as intratext across the bridge. Night time.

- Where? The Eider Duck Inn, Richmond, Van Diemen’s Land (now called Tasmania), Australia. Richmond is not far from Hobart, to the NNE. I’m not sure if The Eider Duck Inn was a real place — let me know if you have the answer.

- Weather: windy, rainy, with lightning.

Pictured above is The Richmond Bridge.

The Richmond Bridge is a heritage listed arch bridge located on the B31 (“Convict Trail”) in Richmond, 25 kilometres (15.5 mi) north of Hobart in Tasmania, Australia. It is the oldest stone span bridge in Australia.

Wikipedia

STORY STRUCTURE OF THE CIDER DUCK

SHORTCOMING

Well, the duck gets drunk. Drunk on fermented apples, to be specific. This isn’t on the page, but deduced after she wanders into the kitchen and ‘falls asleep’ so soundly that she doesn’t notice all of her feathers being plucked out. Because she is drunk she is powerless to stop it.

I figure this duck had a brush with death by alcohol poisoning. The child audience believes the little duck is gloriously happy frolicking about in the utopian world of wind-fallen fruit, finally getting so tired she simply nods off.

DESIRE

All the duck wants is to walk about eating delicious things.

We assume she does not want to be eaten herself. But she’s out to it. Instead, this desire is transferred to the child audience, now reading a harrowing story about a duck who’s about to get cooked.

OPPONENT

The duck is more duck-like than human-like, though we are to believe the duck has human emotions (such as pride, in the end). Therefore, the plot revelation is had by the human main character — the ‘kind hostess’ realises the duck wasn’t dead at all. It was simply asleep.

So the duck’s opponent also functions as the human proxy after this harrowing near-death experience.

PLAN

To make amends, the hostess knits jumpers for the duck — one for every day of the week. Here I am reminded that the creators of this book had pedagogical interests — this sequence feels like an overt exercise in teaching young children the days of the week.

We see the teaching of the days of the week in a Little Golden Book from around the same era — The Tawny Scrawny Lion. This was also the era of ‘animals who aren’t quite animals but aren’t quite human, either’.

By the time The Cider Duck was published, half a century had passed since Beatrix Potter, but Potter’s influence remained strong. Reading these stories today, they seem horrific. Sure, the animals seem to live in utopias with beautiful forests full of food, but death lurks behind every corner. There may be food on the ground just waiting for you to enjoy it, but you yourself are food for someone else.

BIG STRUGGLE

The modern reader may find the plucking scene disturbing in itself.

Live plucking causes birds considerable pain and distress. Once their feathers are ripped out, many of the birds, paralyzed with fear, are left with gaping wounds—some even die as a result of the procedure.

Down Production: Birds Abused for Their Feathers, PETA

But in this book from 1969 we are to imagine being plucked as akin to taking one’s clothes off. This is therefore not the Battle scene of the plot.

For that we get a trope borrowed from cosmic horror. I’ve recently seen this trope given a name: ‘Spatial Horror’.

When the Cider Duck wakes up and doesn’t know where she is, she is completely disoriented and falls into a dark hole. (Actually off the table.)

I’d offer this is a picture book example of spatial horror. It also marks the end of the Big Struggle sequence.

ANAGNORISIS

The Anagnorisis phase gives way to the utopian world of the apple orchard. The duck is basically famous now, for her ability to escape death. She becomes a local celebrity.

The anagnorisis in this story is implicit — after admiring herself in jumpers, the duck seems to realise her value. The humans will not eat her, because they have welcomed her into the human world, removing her from the menu. She must realise at some point that she is safe.

NEW SITUATION

The Cider Duck becomes the mascot for the inn. This is her job now.

This is a different take on the rags-to-riches tale — it’s the menu-to-mascot tale.