The chimney is a multivalent symbol in storytelling. Chimneys can be cosy and welcoming.

A column of smoke rose thin and straight from the cabin chimney. The smoke was blue where it left the red of the clay. It trailed into the blue of the April sky and was no longer blue but gray. The boy Jody watched it, speculating. The fire on the kitchen hearth was dying down. His mother was hanging up pots and pans after the noon dinner. The day was Friday. She would sweep the floor with a broom of ti-ti and after that, if he were lucky, she would scrub it with the corn shucks scrub. If she scrubbed the floor she would not miss him until he had reached the Glen. He stood a minute, balancing the hoe on his shoulder.

Opening paragraph to The Yearling (1938)

Chimneys can also be scary. A few years ago I turned up at our local country bookclub and assumed the host had been slow cooking meat for dinner. Others entered one by one and assumed the same. The grim truth was revealed; a possum had fallen down the chimney. I won’t go into further details because they are gruesome and tortuous. But I’ve heard the story more than once. Owning a chimney, at least in Australia and New Zealand, puts wildlife at risk.

Certain wildlife is attracted to chimneys, sometimes because they’re trying to find a hidey-hole to escape a predator, and sometimes, I wonder, if they are attracted to the heat in wintertime.

Then there’s the risk of chimney fires. When I was six years old our family was eating dinner at the table when the next door neighbours’ chimney went up in flames. The firefighters seemed to arrive almost instantaneously. The following morning I reported this event for news, and embellished the story by saying the firefighter’s hat had fallen down the chimney. Everyone seemed to believe me. I hadn’t expccted that part. Even the teacher laughed. My morning talks grew more and more outlandish after that.

It’s difficult to imagine what it was like to live in earlier eras. I recently re-read Little House On The Prairie, in which the chimney goes up in flames. This was pretty much definitely going to happen to you if you lived 100 years earlier than now. In another chapter, Pa definitely thinks that they caught malaria because of night vapors. What’s not on the page: He thought that the air coming into the house at night was making them all sick. The log cabin was made from self-hewn logs and they went to much effort to plug them up. But you can never plug up a chimney. The chimney remains dangerous, symbolically as well as actually. Believe it or not, chimneys themselves were once made of wood.

For a brief history of the hearth, and its importance across the history of art, see a previous post.

Whereas the hearth often functions metonymically for ‘home’, chimneys are a different matter in storytelling. Chimneys are dangerous.

Doors and windows are also dangerous, for the exact same reason: they let evil in.

But chimneys are worse than doors and windows, because with an old-fashioned open fireplace, you can never shut them off. Lying awake at night, scared of the noisome vapours outside, you can’t help but feel some kind of supernatural creature will come down that chimney, especially after the fire dies out.

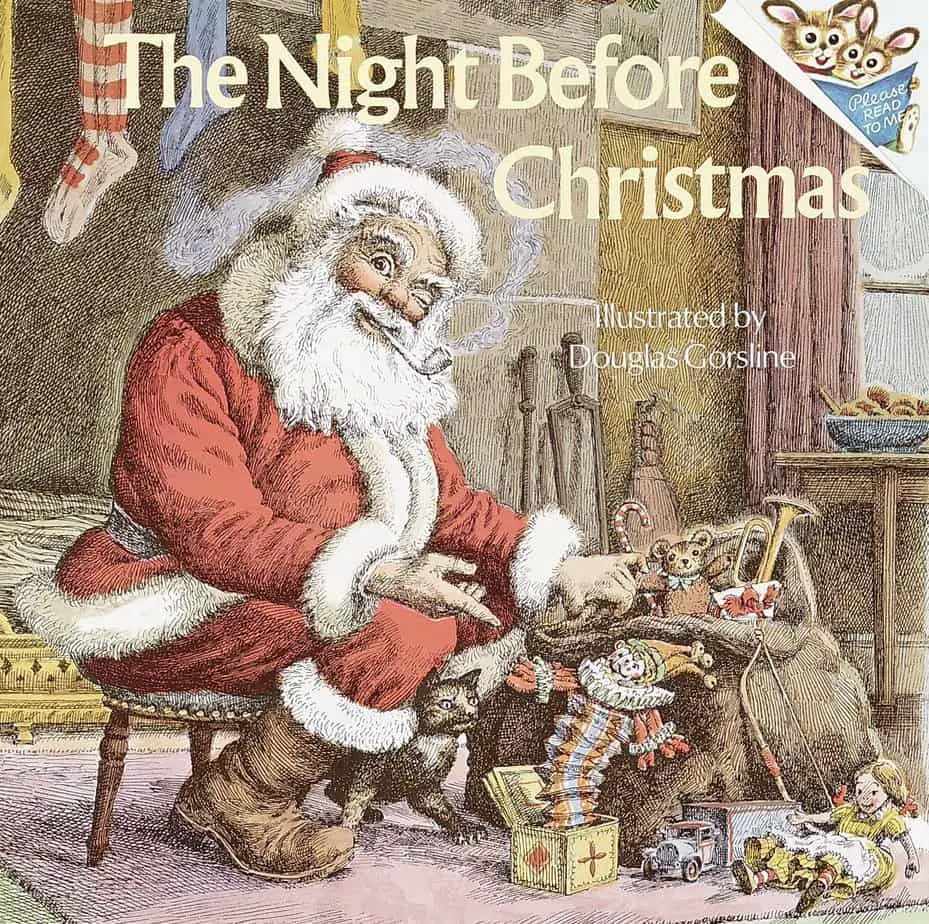

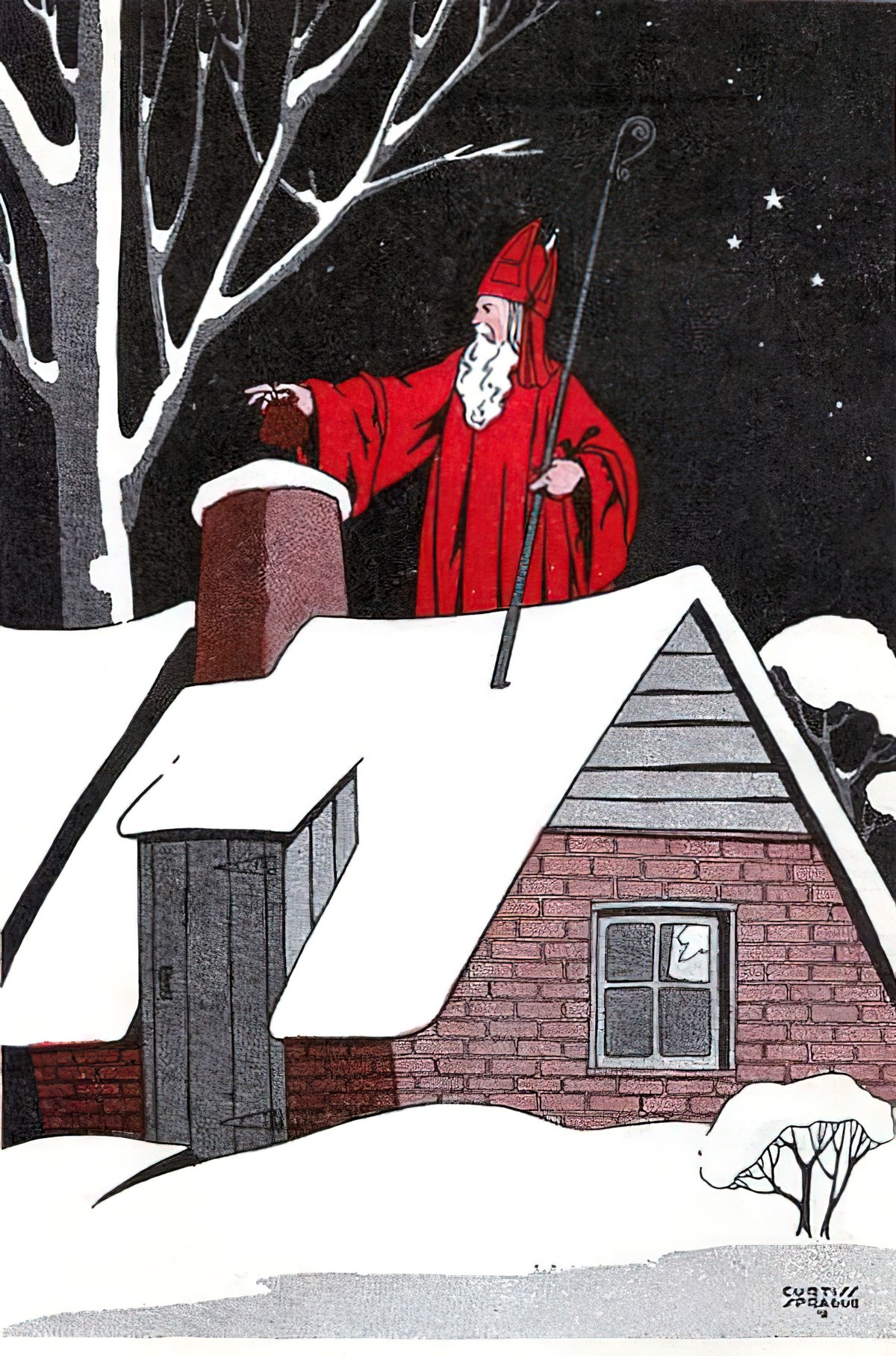

Perhaps this accounts for the proliferation of stories which aim to reassure children that only good things come down the chimney. The standout example is Santa mythology.

As witch expert Diane Purkiss explains on Episode 83 of the English Heritage podcast:

Santa Claus is a sanctified chimney demon.

In the Early Modern period it was very common to believe there are scary chimney demons, especially in the outer isles of Scotland. People would leave food out for chimney demons to pacify them, like children leave snacks for Santa.

In other countries such as the Netherlands Santa is accompanied by a demon figure, such as Black Peter, who will give you a lump of coal instead of a present if you’ve been naughty rather than nice. This plays into identity politics today. Historically, at least part of the reason he is black is because he is sooty. That’s also why Satan is black all over — not racially but because he has come from the chimney.

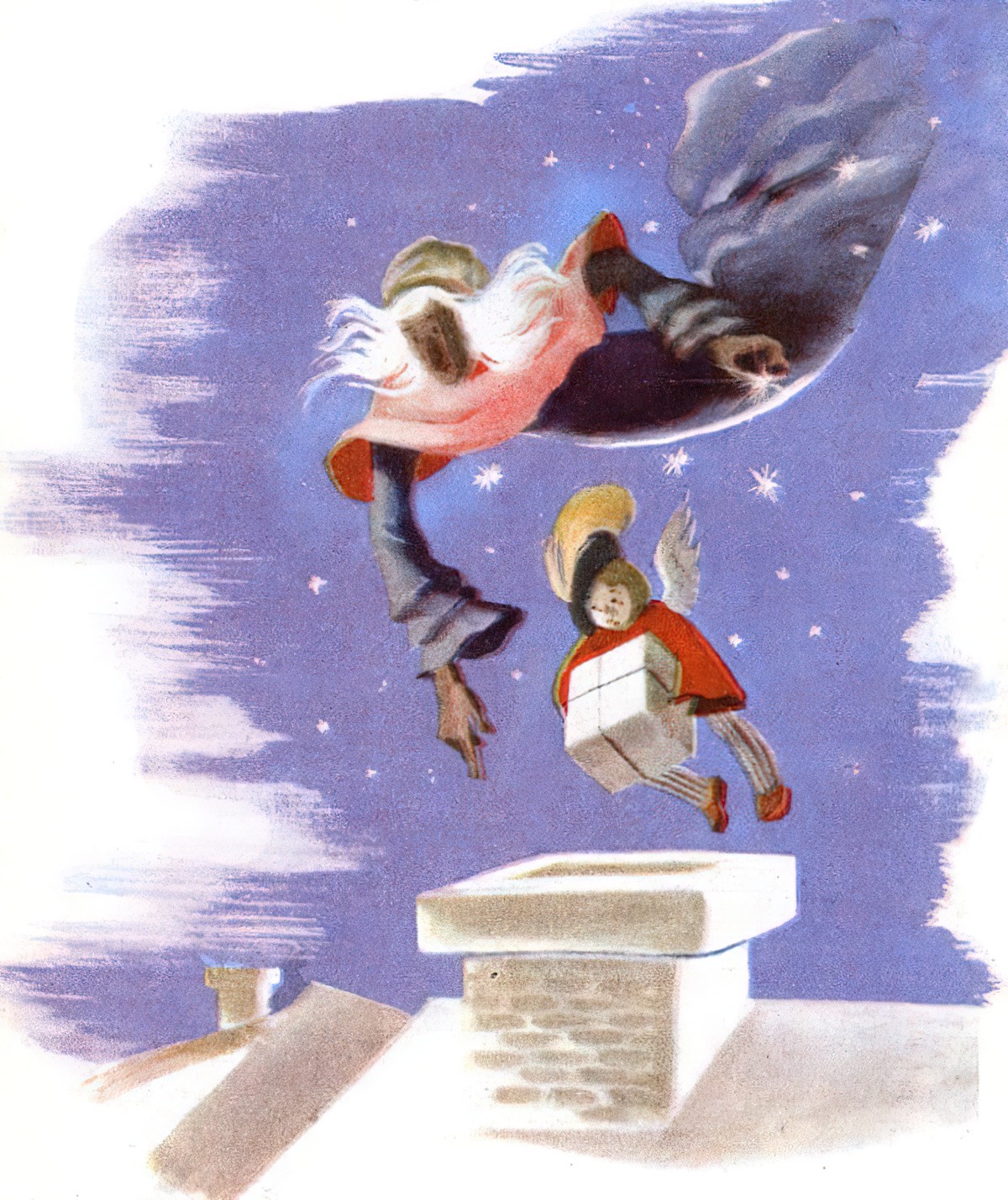

For those who like the Santa tradition but want more of a religious symbolism attached to their religious holiday, here’s an angel depositing toys down the chimney.

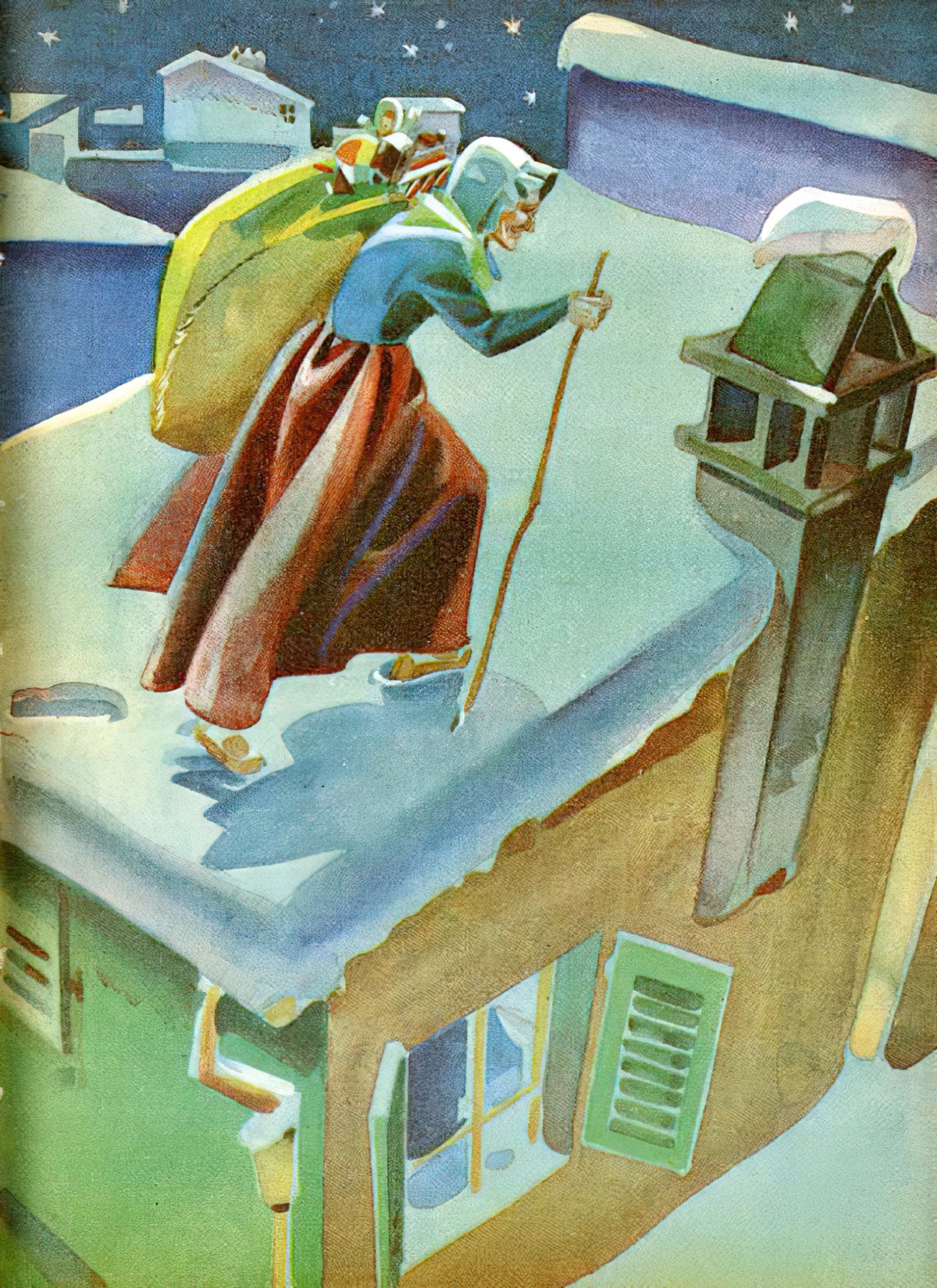

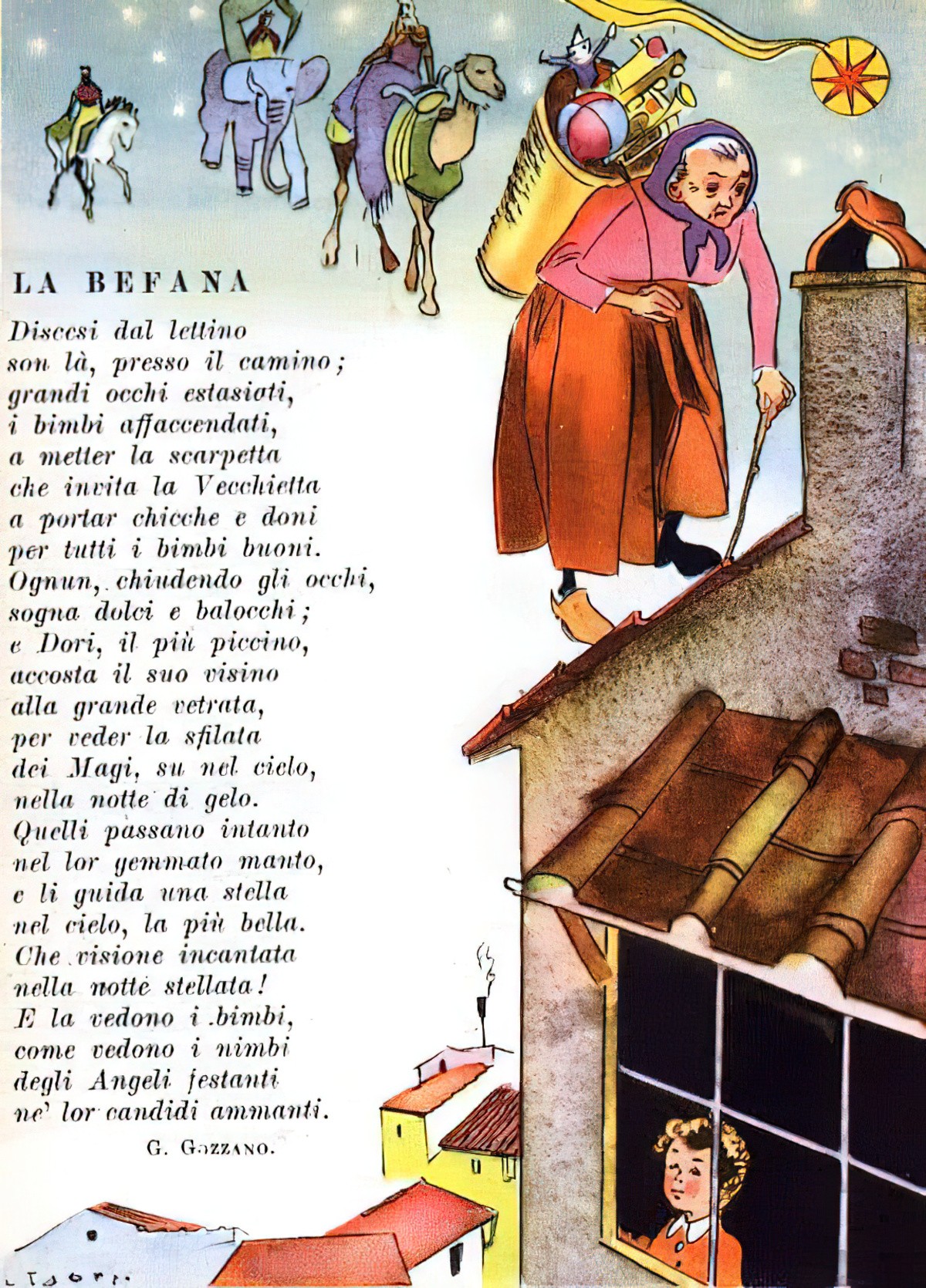

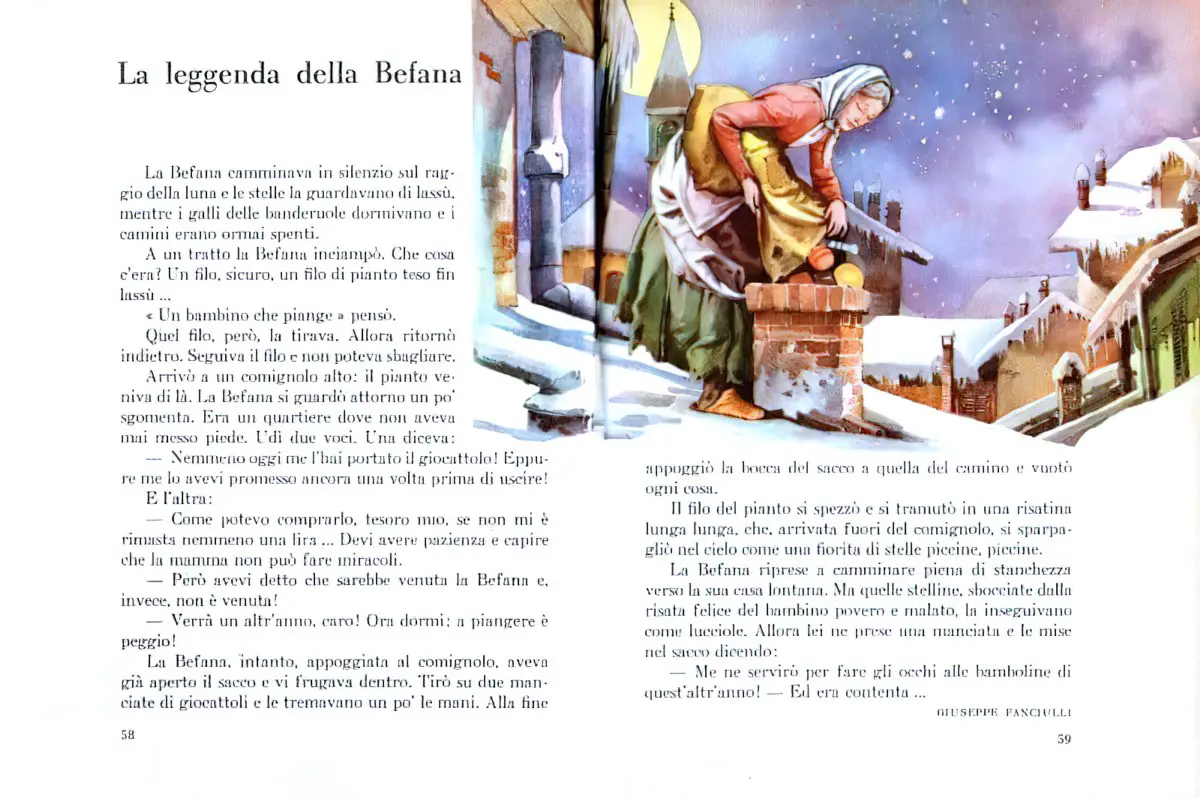

BEFANA

In Italy, it is a witchy old woman called Befana who delivers gifts to children on Epiphany Eve (the night of January 5).

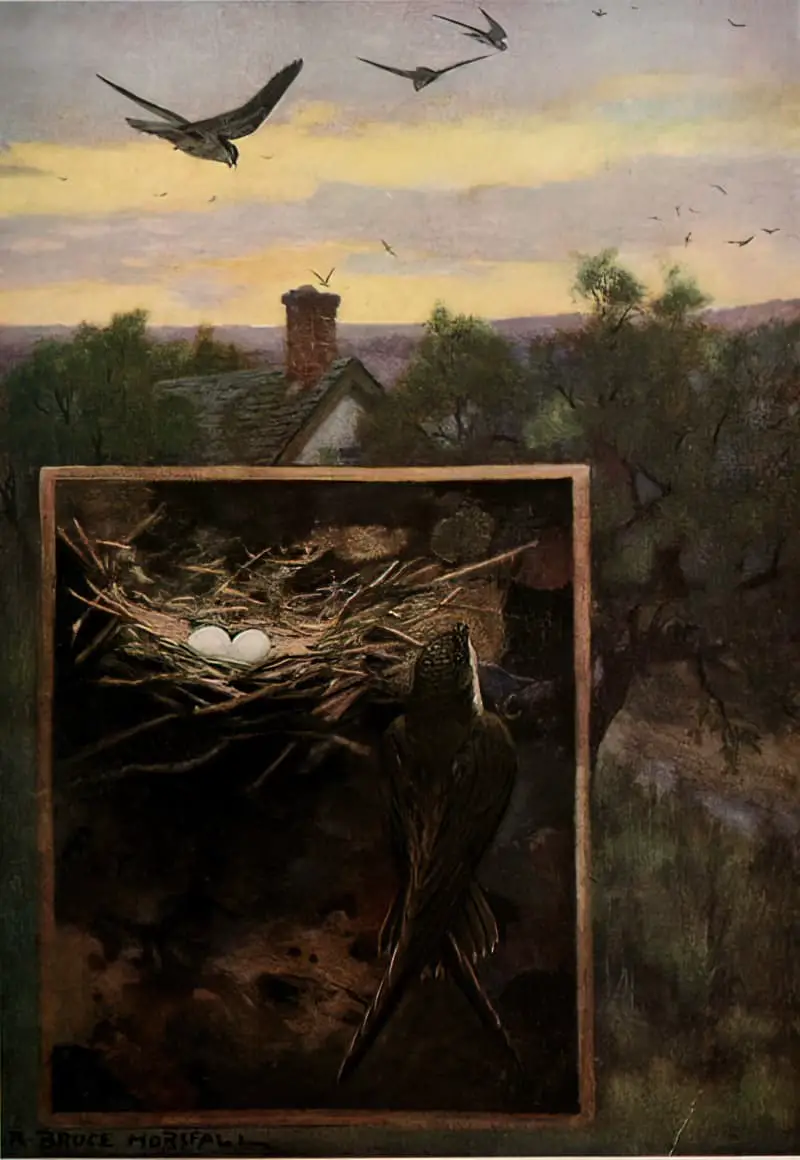

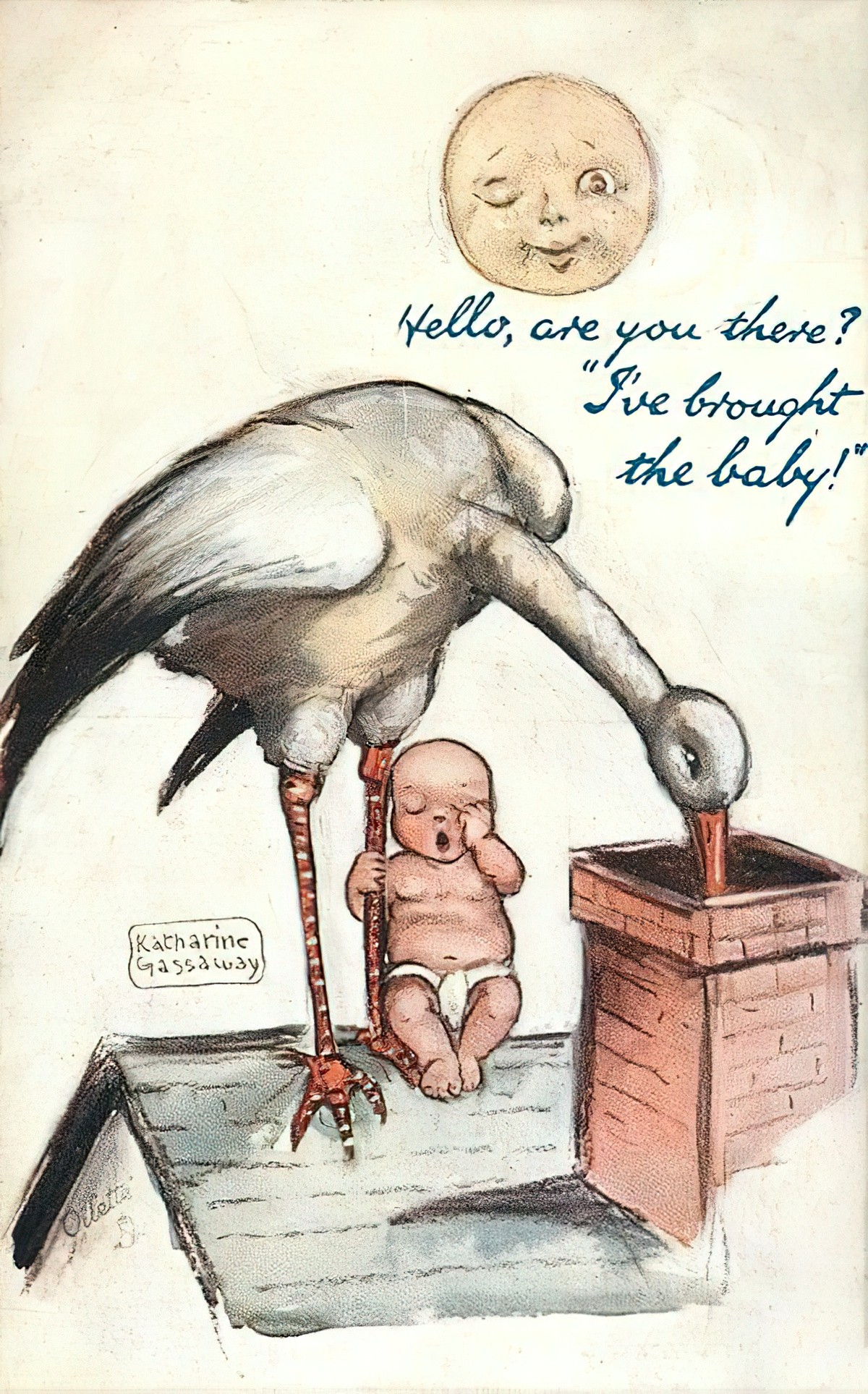

CHIMNEYS AND STORKS

When it was taboo to tell children about childbirth and biology, the stork story did the rounds. Like Santa, the stork might drop a baby into the chimney as a present.

THE CHIMNEY CORNER

Z18.Z* Old woman keeps asking, “Who’s going to spend this long lonesome night with me?” Bear replies after question, in order: “Me by corral;” “Me by brushpile;” “Me by chimney corner.” He eats her up. CALIFORNIA:(from Arkansas): Lowrimore CFQ 8:157, 1945

in Baughman’s Type and Motif Index of the Folktales of England and North America by Ernest Warren Baughman 1966

Note that the ‘chimney corner’ is completely different from the ‘chimney’. The corner between the wall and the hearth is cosy.

Children’s literature makes much use of the hearth and chimney as a cosy symbol of home. In the picture blow, Garth Williams despicts mice using a found pipe as their chimney. (Today we’d call it upcycling.)

Sometimes I find the chimney can be both ominous and cosy in the very same image. A standout example of that is in the hygge/scary painting below, by Charlotte Sternberg. The thin wisp of smoke coming out of the chimney suggests a pleasantly warm fire and hearth, as does the light coming from the windows, casting those squares onto the blanket of snow outside. But why has the man been called to the barn? Why is the dog excited?

The painting below gives some indication of the smoke people used to put up with in their buildings. The painting is both cosy and dangerous:

This watercolour painting shows a scene from the poem ‘Tam O’Shanter’ by the Scottish writer Robert Burns (1759-1796). The narrative poem explores myths and fears surrounding the night and warns against the dangers of drink. This image shows Tam merry-making in front of a cosy hearth before he ventures out into the darkness and is chased home by witches.

V&A

The painting below by Briton Riviere hints at death thoughts of an earlier time. In the Medieval and Early modern era, people might open a window for a dying relative so that their soul would easily ascend to Heaven. I can’t help but wonder if this served double duty, hastening their demise as they shivered in a freezing cold room, but now we all know a lot more about how viruses work, by increasing the ventilation in a house, even over winter, other family members may have been spared from certain viruses, perhaps.

The man below doesn’t sit by a window; he sits by a fire. But the flue provides an escape for his soul. The deadness of the fire of course mirrors the deadness of the man. The picture may be grim as all get out, but very similar imagery can be seen in an Australian picture book from 1979: John Brown, Rose and the Midnight Cat. Windows, doors, the hearth (and chimney) and linear divisions must be read symbolically before readers get another level of meaning out of that story. This is so that the youngest readers don’t have to deal with the death plotline unless they’re developmentally ready to see it. The painting below works the same way. A child looking at it may simply assume the old man is sleeping, and the dogs have come to wake him up. Cute! It takes some years to read the other symbolism and infer death.

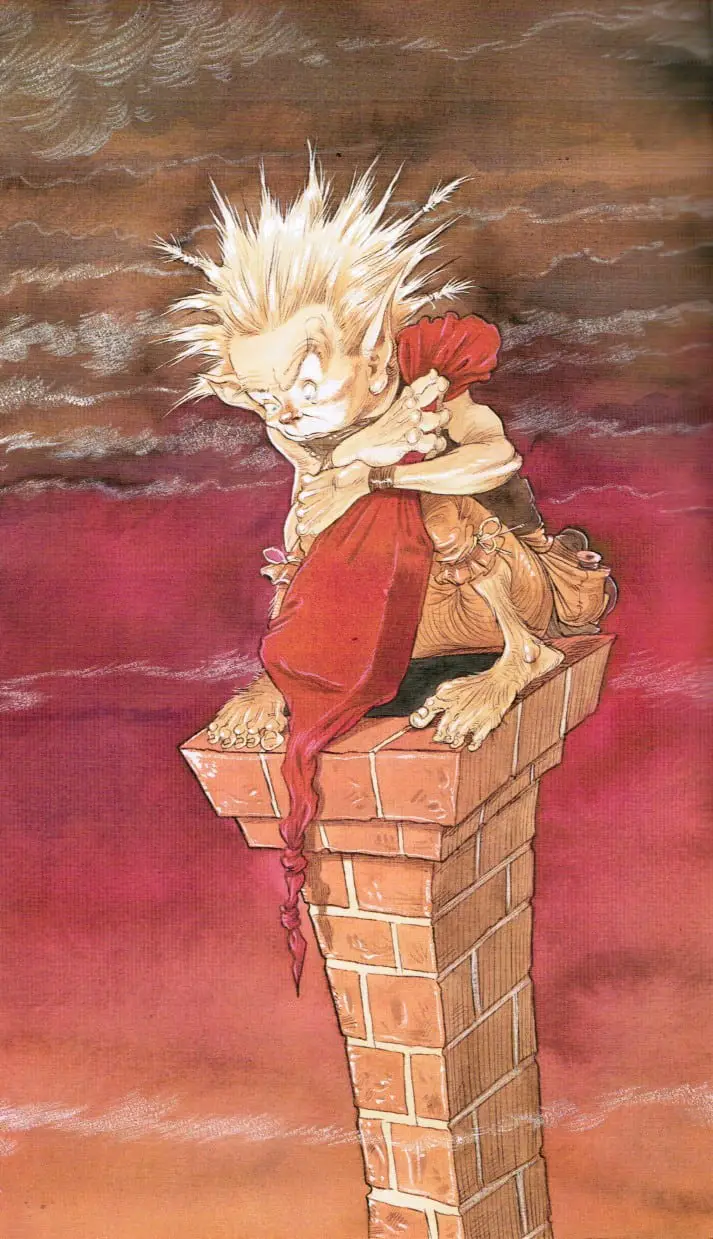

SOOT AS SPIRITED CREATURE

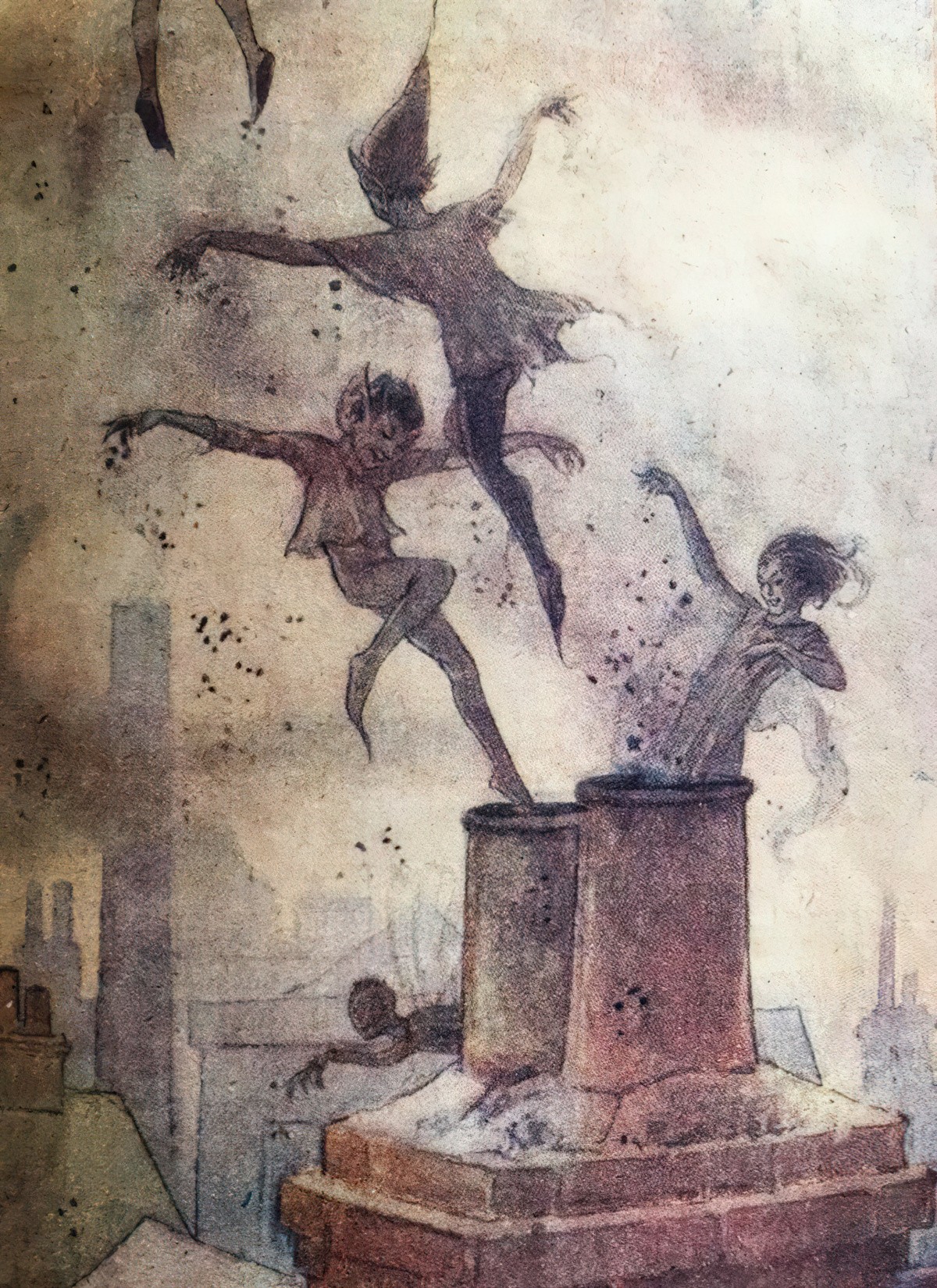

For as long as humans have had thoughts, they’ve had thoughts of some kind of fairy inhabiting every possible nook and cranny, in nature and in the house. There are many examples of artwork in which fairies dance across rooftops, but when I say ‘fairy’, I don’t necessarily mean the small, cute, winged creatures of the image below. I mean any kind of supernatural creature, who exist on the moral spectrum from evil to good.

How have cultures across the globe imagined the supernatural creatures of chimneys?

And how far back can we find terrible tales about chimney creatures in folklore and storytelling? They go back to antiquity, and before there were chimneys, there were open fires. Diane Purkiss writes about a demon called Mormo:

Games were played between mother and child in the ancient world … as the story of the demon Mormo illustrates. Mormo is somehow vague; she seems to have begun as a mask of the god Hermes, daubed with ashes to frighten children. This is a ‘chimney-demon’, one of the demons of darkness … One anonymous writer speaks of Mormo as a name whose utterance frightens children, but also tells a story about her; ‘they say that she was a Corinthian woman who, one evening, purposefully ate her own children and then flew away. Forever thereafter, whenever mothers want to scare their children, they invoke Mormo.

Diane Purkiss, Troublesome things: A history of fairies and fairy stories

If you want to really scare children, make the demon female (like Mum, who tucks you in), and make her a cannibal.

The Blue-Legs Garrules is a Spanish femme coded child-eater who enters houses through chimneys. She is most probably a descendent of the Mormo. Another is the Caranjaina. The Pardalot is a bird that feeds its chicks with human children and enjoys the warmth of fire and smoke, entering houses through the chimney.

The trasgu or trasgo is another creature from Spanish folklore. He’s similar to a brownie. He lives in the house and to keep him happy, you have to let him have a comfy spot near the fire. From what Ican gather, he was sometimes thought to arrive down the chimney. Clearly, supernatural creatures coming down chimneys are significant in Spanish folklore.

(For a comprehensive list of creatures from Spanish folk creatures, see this thread.)

GRIMM CHIMNEYS

For one fairy tale example, check out “The Devil’s Sooty Brother“. Japanese folklore is also full of spirited soot, and Hayao Miyazaki keeps that folklore alive in Spirited Away and in My Neighbour Totoro. In Japanese they are called susuwatari, loosely translated as Wandering Soot. Miyazaki has actually changed the name of these spirits by giving them a particular name: Makkuro kurosuke. I’m not surprised that caught on in Japan because it’s a wonderful phrase to say. The closest we have in English is dust bunny, but the Japanese version is sootier.

These Japanese soot spirits don’t necessarily come from a chimney, but if you happen to live with a fireplace, you’ll appreciate that fires are your main source of dirt in the house during winter.

WITCHES AND CHIMNEYS

Now to witches. Of course witches and chimneys go hand in hand. Witches are basically old women, and people are historically scared of old women because old women remind people of death. Compounding the association, women are associated with the home, and the hearth is metonym for home. Who cleans up after a fire? Housewives and female maids. What do you use to clean up around a hearth? A broom…. Of course your mind is going to conjure up images of deathly old women coming down your chimney in the dead of night. How did they get up on your roof? They flew there, on their broomsticks.

It’s not much of a leap at all to suggest strange old women be burned.

Fairytale is full of stories in which old women meet a fiery demise. This, too, is meant as a comfort against the idea that a witch can come down your chimney. Ah, but in this particular story, the situation is reversed. She gets pushed into the fire.

BEATRIX POTTER

Don’t make the mistake of thinking Beatrix Potter wrote cosy stories for children about cute animals dressed in clothes. Potter wrote horror that’s way more scary than anything R.L. Stine has churned out. The Roly Poly Pudding has traumatised many of your parents and grandparents. Naturally, household fire is involved, and a chimney that makes full use of the tropes of spatial horror.

THE AWFUL BUGABOO

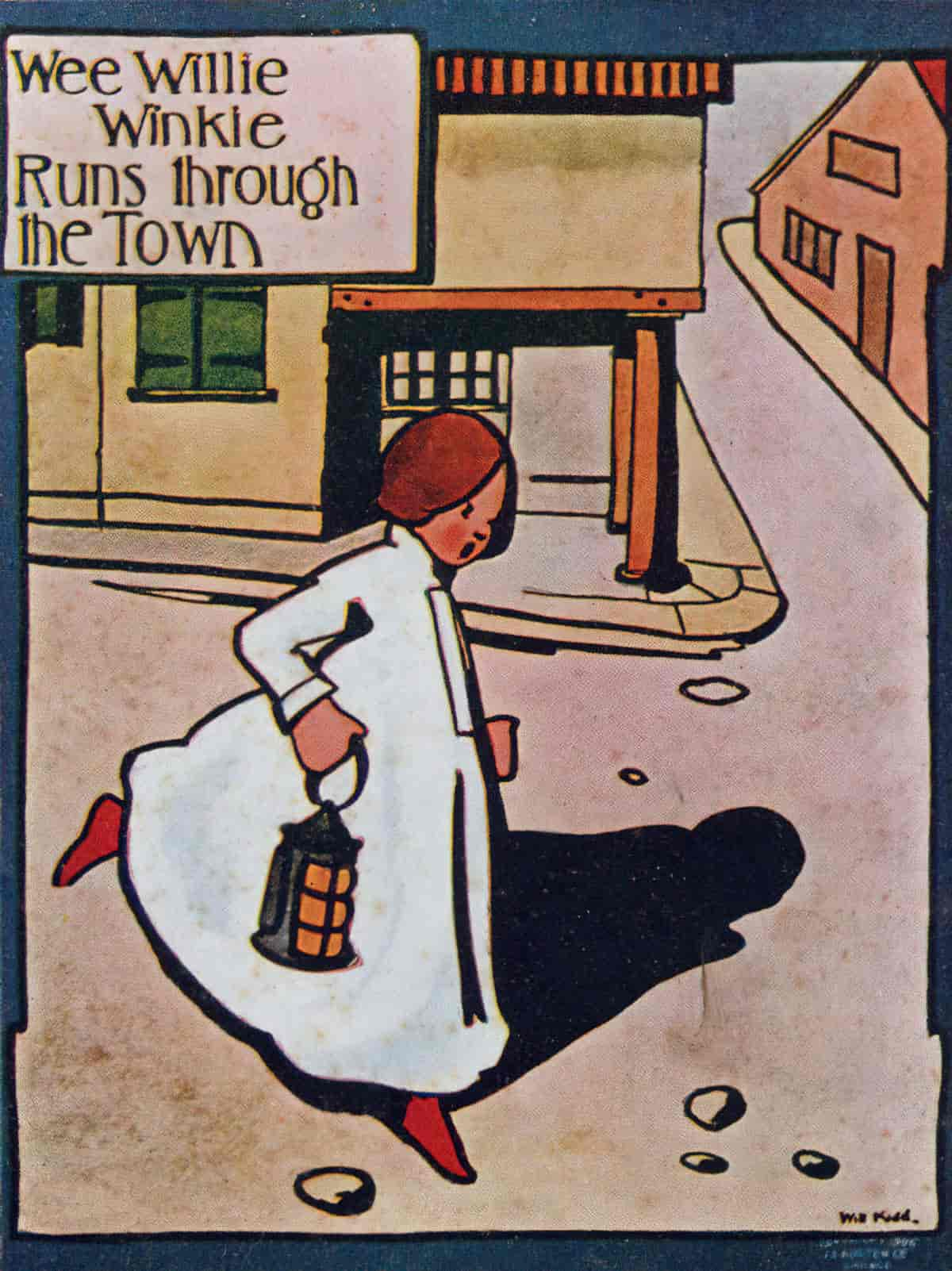

Did you enjoy bedtime stories and lullabys as a child? I got Wee Willy Winkie when I played up at bedtime and that scared me enough, but I’m pretty glad I never got the Bugaboo, like children of the Victorian and Edwardian eras. We find the story in written form in 1901:

There was an awful Bugaboo Whose Eyes were Red and Hair was Blue; His Teeth were Long and Sharp and White And he went Prowling ’round at Night.

A little Girl was Tucked in Bed, A pretty Night Cap on her Head; Her Mamma heard her Pleading Say, “Oh, do not Take the Lamp away!”

But Mamma took away the Lamp And oh, the Room was Dark and Damp; The little Girl was Scared to Death — She did not Dare to Draw her Breath.

And all at Once the Bugaboo Came Rattling down the Chimney Flue; He Perched upon the little Bed And scratched the Girl until she bled.

He drank the Blood and Scratched again — The little Girl cried out in Vain — He picked Her up and Off he Flew — This Naughty, Naughty Bugaboo!

So, children, when in Bed to-night, Don’t let them Take away the Light, Or else the Awful Bugaboo May come and Fly away with You!

Poems for Old And Young (the old to scare kiddies with; the kiddies to be scarred for life, I take it).

THE CHIMNEY SWEEP

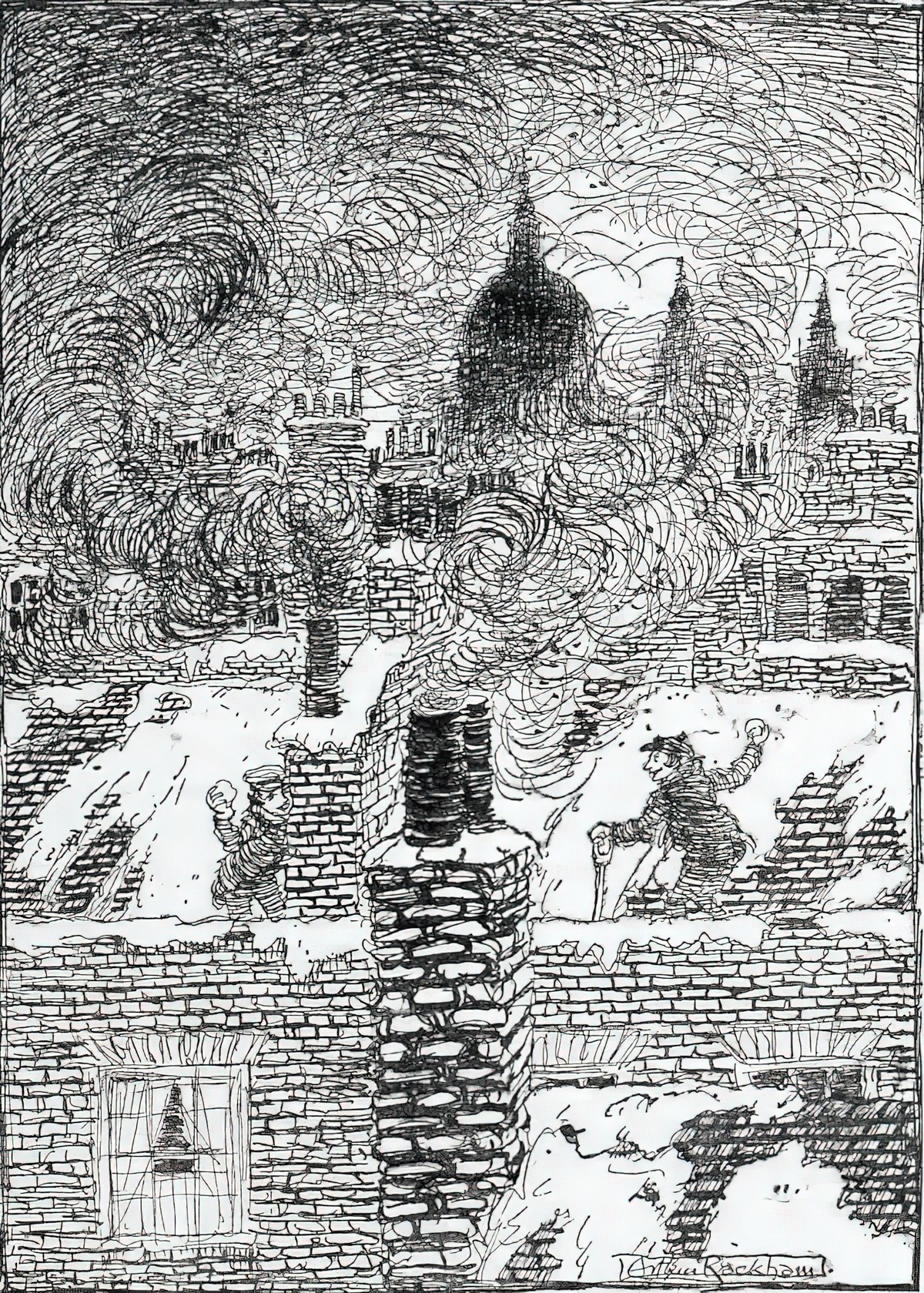

It’s difficult to imagine the big cities of earlier eras, with coal smoke billowing into the skies, dominating the skyscape, but Arthur Rackham’s illustration below does an excellent job.

That we ever used small children for the dangerous job of cleaning chimneys is a blot on humanity. See A Brief History of Chimney Sweeps.

Because the chimney sweep child is a pathos inducing underdog, Hans Christian Andersen liked him.

Tales of bugaboos are one thing. But for those children used as chimney sweeps, the terror of the chimney must have been another level of horror.

Header painting: Fred Cecil Jones (British, 1891-1956) – Chimney stacks and winding ways, 1936