Historical fiction for young people…follows in the footsteps of the adult historical novel, the only difference being that it often chooses a hero of its readers’ age, who has a mentality and psychology close to those of our children and teenagers.

Thaler, 2003, Understanding Children’s Literature

The belief in historical fact qua fact is if anything stronger [in children’s historical fiction than in children’s historical non-fiction] … Historical fiction for children acts as history improved, a superior replacement for the real but flawed thing. The genres are starting to trade places. History is offering possibilities, while fiction offers certainty…history is undercutting the authority of narrative while historical fiction still clings to it, asserting itself as more real than fact because it is a better story…The change in historical fiction has been the embrace of relativity, the idea that someone else is going to see a different part of the past, but history begins to suggest the possibility of complete subjectivity — that no one is seeing the past quite right and that the stories will not match up.

Stevenson, 2003, Understanding Children’s Literature

How do you feel about the terms ‘historical fiction’ and ‘historical novel’? Do you agree with author Hernan Diaz below?

I find the term historical novel abysmally depressing. To begin with, proposing that such a thing exists would also imply the existence of an ahistorical novel, and I’ve yet to come across one of those.

But in addition to being rather useless, this category is actually disrespectful to fiction. Because this notion implies a hierarchy: there is history, which is supposed to stand in a closer relationship to truth, to be verifiable, to be fact-based, and then there is fiction, which is a mere fancy totally divorced from truth.

Yet haven’t we been taught, over and again, how much of history is fabricated? Haven’t historians repeatedly shown us that many of the accounts taken to be true for decades or centuries can be debunked as ideological narratives? And conversely, isn’t there a robust body of fictional texts that throughout millennia have shown us at least a hint of truth (however mutable this term may be) about what it means to be human? In short, I’m not into “historical fiction” and refuse to accept it on the ground of the use of “period” props or costumes. I would even say that Trust aims, to an enormous extent, to question the boundaries between history and fiction.

Hernan Diaz, author of Trust

A brief history of historical fiction for children

The following are notes from Genres In Children’s Literature: Lectures 15 & 16: Historical Realism which used to be available on iTunes U.

- Historical fiction began with Sir Walter Scott (1771-1832). He is most famous for Waverley, The Heart of Midlothian and Ivanhoe.

- Historical fiction for children has always needed to find favour with book buyers — parents, librarians and teachers.

- The work of Charlotte M. Yonge (1823-1901) is a great place to start for examples of ethics and accurate research and pious, morally upright behaviour. For example, The Little Duke (1854)

- Overt didacticism is no longer the aim of modern children’s historical fiction — rather, it’s meant to teach children about the past as well as entertain.

- More recently, publishers were under the impression that children did not like, read or buy historical fiction so for a long time there was very little of it published.

- That all changed with the American Girls series.

- Ann Rinaldi and Kathryn Lasky are superstar workhorses in this subgenre.

- Here in Australia, the equivalent is Jackie French.

- The American duology about Octavian Nothing by M.T. Anderson is a stand-out example of excellence in historical children’s literature, published 2006.

The advantages of historical fiction over non-fiction

- The reader is able to empathise with a particular character caught in that time and place.

- Fiction can portray what ordinary life was like, rather than focusing on the politics and big struggle fields. This allows for the inclusion of women in history, who were genuinely excluded from the history-book-making events, even though fully invested and involved in society.

- Young readers can learn that the difficulties of adolescence are universal, not just across cultures but across times.

The following are notes from a lecture by David Beagley, La Trobe University, available on iTunes U.

The past is a foreign land. They do things differently there.

L.P. Hartley

Readings

Winters and Schmidt, Edging The Boundaries Of Children’s Literature. This is a good outline. (Especially Cullinan and Goulder’s chapter.)

In Australia: Jackie French, who started off writing humorous books but more recently deal with historical realities.

The three types of historical story

1. A bit of the scenery is historical.

2. Fictionalised history. The time period is the key thing. The plot is fictional.

3. Real events and people, with another story slipped into the cracks between.

Historical fiction can be more real than realistic fiction.

Sadako and the Thousand Paper Cranes is a biographical story because Sadako was a real person. So many elements of any story are determined by the setting chosen by the story. Authenticity is essential. If a story is set in the past, we have records. Other people can see how accurate the details are, from the clothing worn by the characters to the food they eat.

The concerns expressed in historical fiction will be different from those expressed in modern works. For example, environmental concern is a modern concern.

A book is often a child reader’s a first contact with a historical situation.

A problem encountered by authors can be lack of information about the era. This is an issue encountered by authors such as Jean M. Auel.

Blacklock’s Pankration was published at a time when drug cheating in the Olympics was starting to make headlines. We have no evidence that this was a problem in the early history of the Olympics, when this story is set.

The Ramose series by Carol Wilkinson looks at Egyptian Pharoahs with all the inter-family feuding is detailed in the tombs, so the author does have a responsibility to make sure it does not contradict the evidence that we do have.

Historical fiction must be balanced with the fact that history is real but fiction is not. Historical fiction must be ‘realistic’ if not ‘real’. The reader must believe the story could have occurred, not that it did.

See also: Another taxonomy for types of historical fiction.

Language

When historical facts take centre stage, a difficulty for the writer is keeping the prose from reading like an encyclopedia. Another difficulty is that English language has changed a lot across the centuries — more than most people would guess — and so the writer must invent some sort of hybrid English which avoids obvious uses of modern language, while guesstimating which words are going to be acceptable as shared by an earlier era.

Australian Examples Of Historical Fiction

Tangara is an Australian historical novel set in Tasmania. A white farm girl encounters an Aboriginal girl.

Ruth Park’s Playing Beatie Bow is set in the slums Sydney in the late 1800s.

My Place is a picturebook by Nadia Wheatley, originally published in 1988 but since rewritten (2008). The reader is taken back to the same place in Sydney, in ten year jumps. (2008, 1998, 1988…1788).

There is now a TV series based on this book.

Our Australian Girl (like Our American Girl), My Story, etc. are series which depict fictional characters in real historical situations.

The Time-Slip Technique

A common technique employed by authors of historical fiction is the ‘time slip’. Hitler’s Daughter, Playing Beatie Bow and Tangara all make use of this technique. A character from the present world of the story has a bridge to an earlier time. This makes for a kind of (portal) fantasy story.

It’s important that the reader identifies with the main character, so that the reader is interested enough to learn about the historical parts. The aim is for the readers to feel as if the story is happening to them.

Historical fiction is relevant to young readers because history has contributed to our very existence, and has contributed to our culture.

Evaluating A Work Of Historical Fiction

Are events consistent with what we know of the historical era?

Gladiator is one of the worst films for historical inaccuracies. Even his name is inverted. The Romans never put personal names first. Caesar Julius, not the other way around. Women weren’t seen in the Colosseum. There were no outed left-handed people. Left-handed people were burned. There was no letter ‘u’ — they used ‘v’. Paper wasn’t invented so there wouldn’t have been leaflets. Horses had no saddles and no stirrups. There were no Rhode Island Red chickens. There was no welding. Some of the helmets were Anglo-Saxon. Certainly no wrist watches and jet trails across the sky, and no girls wearing jeans.

1. Of the characters who are meant to represent people from that era, are they realistic representations?

Some time in the future, what if people thought of Home and Away or My Kitchen Rules as a guide to how we all lived?

2. Is the reader able to visualise the setting?

If the characters don’t have glass in the windows, how does that affect their daily lives? How do people store their meat without refrigeration?

3. Is the narrator authentic?

Regardless of mode of narration (external/internal) the narrator is an imagined person in that historical situation, so must sound historically authentic. This is problematic because language changes a lot over time, so modern English speakers wouldn’t be able to understand Old English. So the narration must be an approximation. Do characters speak to people in authority the way they would have? Beagley uses the term ‘Gadzookery’ to describe language which is meant to sound old without being a natural replication. [I would add ‘pirate-speak’ to that. Pirates didn’t really speak the way we think they do.]

The TV adaptation of Miss Fisher’s Murder Mysteries is set in 1920s Australia, but all the characters in this series have very similar accents. This wasn’t the case in 1920s Australia, in which there was a significant distinction between how the upper classes and the working classes spoke. The upper classes sounded English. The working class sounded unabashedly so, with different word usage and a vastly different accent. This distinction wouldn’t sit well with an Australian audience, but can jar with people who know a bit about

Brother Cadfael Murder Mysteries are historically accurate, except for the way in which Brother Cadfael makes use of modern medicine.

Problems with balancing modern expectations of good stories against historical realities

For example, do we have a modern feminist character set in Roman times arguing for women’s rights? Beagley argues that this simply didn’t happen. [I argue that we can’t prove it didn’t, though feminist action obviously didn’t get them anywhere, so authenticity depends on the conclusion of the story.] A good example of characters acting out of accordance with their time period is the BBC production of Robin Hood. The role of women was very much out of kilter with the history of the time. In the TV series Maid Marion was a rival for Robin Hood.

Beagley recommends The Pagan Chronicles, a YA series by Catherine Jinks. By the same author, The Inquisitor, a murder mystery.

Is our view of history manipulated by story? One power of story: To present a particular emotional, partisan and one-sided view. When we read a novel we are used to the idea of having a single protagonist as a key element in the story. We empathise with the main character; this is the convention of story.

What happens when we read a story in which the MC is on the ‘other side’?

E.H. Carr is a leading historiographer: He studies how we record history. In What Is History he says that history is a conversation between the present and the past. Therefore we can learn from the past and apply it to the present. In regards to the Aboriginals, for instance, what was seen as an achievement in the past may later be seen as a failure.

Is considered one of the great heroes. But the British called him the ‘little corporal’.

This is a British comedy series only about 10 years old. The same attitude towards Napoleon is conveyed, centuries later.

Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.

All history writing is selective, be it fiction or non-fiction. We can look at Greek archaeology for instance and learn things about the Olympic games. Or we can read a book like Dyan Blacklock’s. The past is being continuously reconstructed by the present, and it keeps changing. What we see as definite points of history will continue to be reconsidered as time goes on.

Erik Haugaard, a Danish children’s writer said something like: When you write a story that takes place in times gone past you are free. Your readers will accept your tale more easily due to less prejudice. But you’d think you’d be more limited. You can’t make things up about the past as a setting. Children of the past are freer in historical novels. They don’t need to go to school or stop at traffic lights, so in that sense there is a freedom allowed in historical settings. It was easier to remain unnoticed.

Benedict Arnold acted as an agent and a spy. He argued that he was simply doing his duty as a citizen of Britain. Was he a hero or was he a traitor by not going along with the revolution? Fidel Castro is another historical character who can be considered both a hero and a traitor, depending on which side you’re on. Ned Kelly is a good Australian example. The author of historical fiction has to pick a side or decide these moral questions, even if the aim is remain neutral.

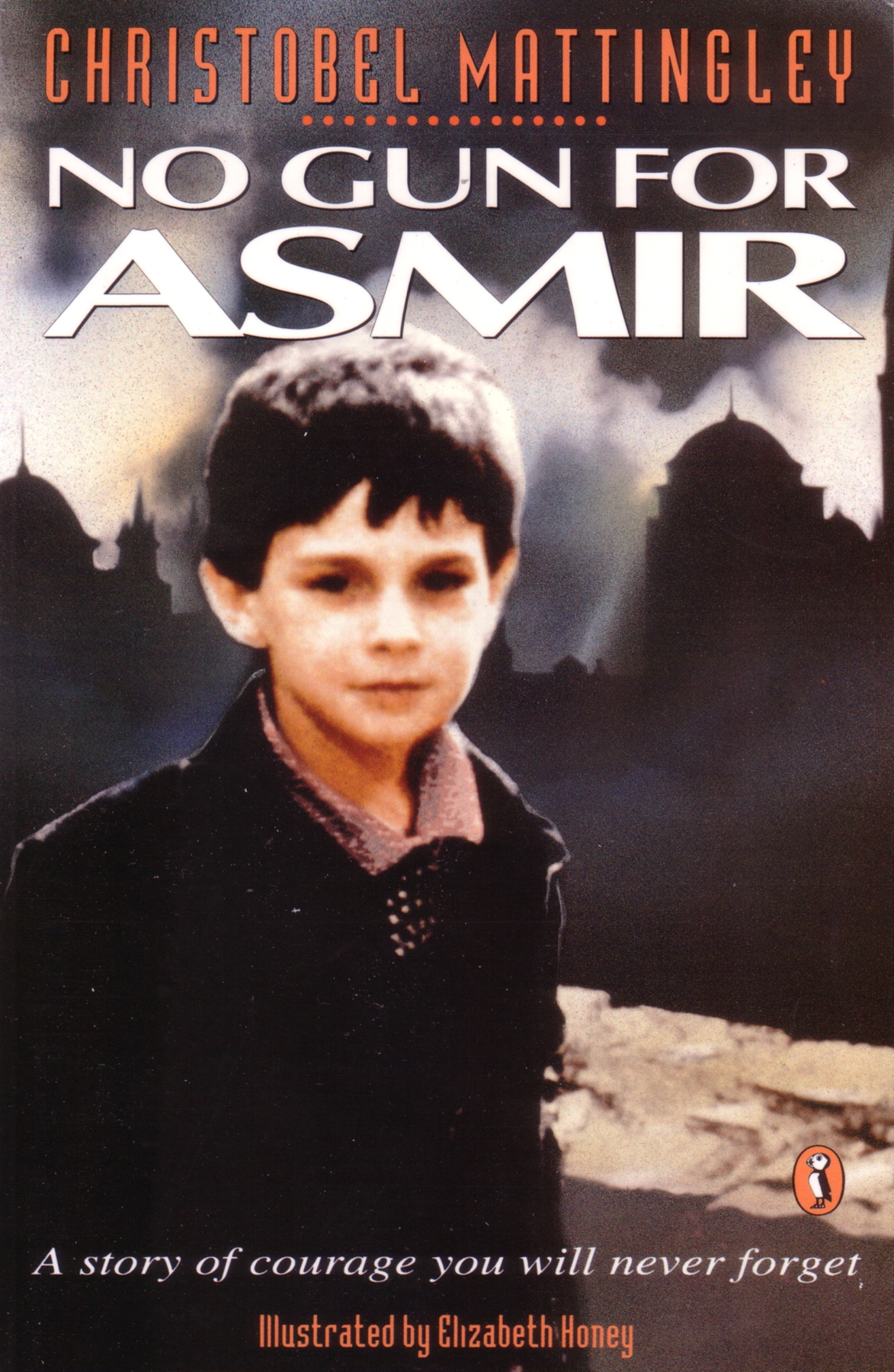

Beagley mentions at this point a book by Christobel Mattingley: No Guns For Asmir. Asmir, like Sadako, was a real person. This one is set in Sarajevo.

Definition of Hagiography

Hagiography originally meant the story of a saint. When we use this word today we’re generally talking about writing which makes out a person from the past was wonderful.

With Sadako and the Thousand Paper Cranes, the author does not take sides, mainly because it avoids the key question: Should the atomic bomb have been dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki? However, indirectly the question is there the whole time. Eleanor Coerr simply gives us the story of a small girl, who begins the story as a healthy school girl keen to make her family proud by running in a relay team. The conversations she has with her mother are fabricated because that was never recorded. Also, the conversations would have been in Japanese. Authors must make up what was not recorded, but include that which was: We all know a bomb was dropped, so that part is not the fictional part. The answer that you come up with regarding the morality of war is your own answer. You are required to make that decision yourself.

Or, is it therefore avoiding the question? Neither child nor adult readers might not be ready to face that one.

Historical works which ask difficult questions

Another book which similarly raises awkward questions is Hitler’s Daughter. Adolf Hitler is generally seen as a bad person. But what if he had a daughter called Heidi, who he kept sheltered during the war? Heidi spends most of the story waiting for her father to come and visit. He is very important. He doesn’t see her much but shows obvious affection, trying to keep her safe. This is a brilliantly constructed story.

- I Am David and The Silver Sword (both about child refugees)

- The Midnight Zoo by Sonya Hartnett

- Diary of Anne Frank about the Holocaust

- Maurice Gleitzman’s trilogy of Once (2006), Then, and Now

- The Book Thief by Markus Zuzak

- Divine Wind by Garry Disher — Set in the seaside town of Broome in northwestern Australia, it opens in 1946, when Hart Penrose—son of a pearl lugger and a race-conscious Englishwoman—begins looking back at his complicated relationship with Mitsy Senosuke, daughter of Japanese immigrants.

See Also

A list of books about ‘The Past’ from Reading Matters

Episode 145 of the Then Again Podcast: Portraying Historical Characters with Gene Harmon. “Museums and other heritage sites have different ways of engaging their visitors with the content and history that they preserve. Two methods of historical interpretation that have been growing in popularity in the past several decades are living history and historic character portrayals. These methods bring history to life and engage the visitor in a personal way, but what goes into creating these historical experiences? A LOT!”