“Charles” is a very short story by Shirley Jackson, first published in 1948. Told in first person from a mother’s point of view, this is the story of a little boy who starts school and immediately transforms from a little boy into a smart-mouthed brat. He talks constantly about a boy called Charles who gets up to all sorts of mischief.

The mother learns on parent-teacher night that Charles doesn’t exist.

The Two Main Reader Responses to the Ending

- Realism: The son Laurie is himself up to all sorts of mischief. By this reading, Laurie is assuaging his guilt by confessing to his parents. This way, he gets to unburden himself, but also avoid punishment.

- Supernatural: Laurie has been describing a ghost. By this reading, all the other children must be seeing the ghost, too, because the other children all play with Charles. The teacher cannot, which means this ghost is the sort only children can see. TV Tropes calls this “Invisible To Adults”.

If we look at Shirley Jackson’s other work, that gives us no clue because she sometimes writes supernatural stories (The Haunting Of Hill House) and at other times realism, often about the evil that exists in small communities (e.g. “The Lottery“.)

A Third Possible Reading Of “Charles”

This theory extends the first reading.

Charles does not exist, and also, none of the mischief is happening. Laurie imagines the mischief. By this interpretation, Laurie is the ultimate unreliable narrator. Laurie is weaving the ultimate wish fulfilment fantasy. He would like to hit his teacher. He would like to throw chalk. But he cannot do any of these things because he is scared of the repercussions. In the 1940s, corporal punishment was a thing. Hell, I was in kindergarten in the 1980s, and I remember my classmates got strapped even then (for pushing another kid off the top of the play equipment). In the 1940s, teachers and parents colluded in the maxim: ‘spare the rod, spoil the child’. (Meaning, if you don’t hit kids with a rod, the kid will naturally be bad.)

The teacher in “Charles” is presumed reliable. Via the teacher, readers do learn that Charles is having trouble fitting in. But what might “having trouble getting used to school” look like? Instead of creating havoc and becoming popular, Laurie could be sitting in the corner, speaking to no one. Charles could be the superhero alter-ego of a socially struggling Laurie. When Laurie describes Charles as ‘bigger than him’, he, himself would like to be bigger. The detail about not wearing the jacket feels like a specifically five-year-old detail to add, and is masterful. (I suspect Laurie is annoyed at having to wear a jacket.)

In support of this reading: By Laurie’s description, Charles has accrued significant social capital with his mischief making

“[The teacher] spanked him and said nobody play with Charles. But everybody did.”

“Charles” by Shirley Jackson

But, in your own experience of school life, would the behaviour of Charles, as described by Laurie, really make the kid popular? Or would the other kids fear and ostracise him?

Mother Blaming

Notice how Laurie’s mother and father both want to meet the mother of Charles. Mothers as wholly responsible for child behaviour holds true today, but is even more obvious in a story from the 1940s.

My husband came to the door that night as i was leaving for the Parent-Teachers meeting. “Invite her over after the meeting,” he said. “I want to get a look at the mother of that kid.”

“Charles” by Shirley Jackson

We already know from “The Lottery” that Shirley Jackson has a special interest in how a community will easily get to the point where they will sacrifice or ostracise someone for the sake of the (supposed) greater good. She does it again here. If Charles really did exist, what do you think would happen to his mother? The poor woman is already being blamed for everything.

By revealing that Charles does not exist, Shirley Jackson hopes to pull readers up short, as well. If Charles literally does not exist, then maybe we should question absolutely everything we think we know about child-rearing and the apportioning of blame.

The early 1940s were a terrible time for mothers of children who did not fit in at school.

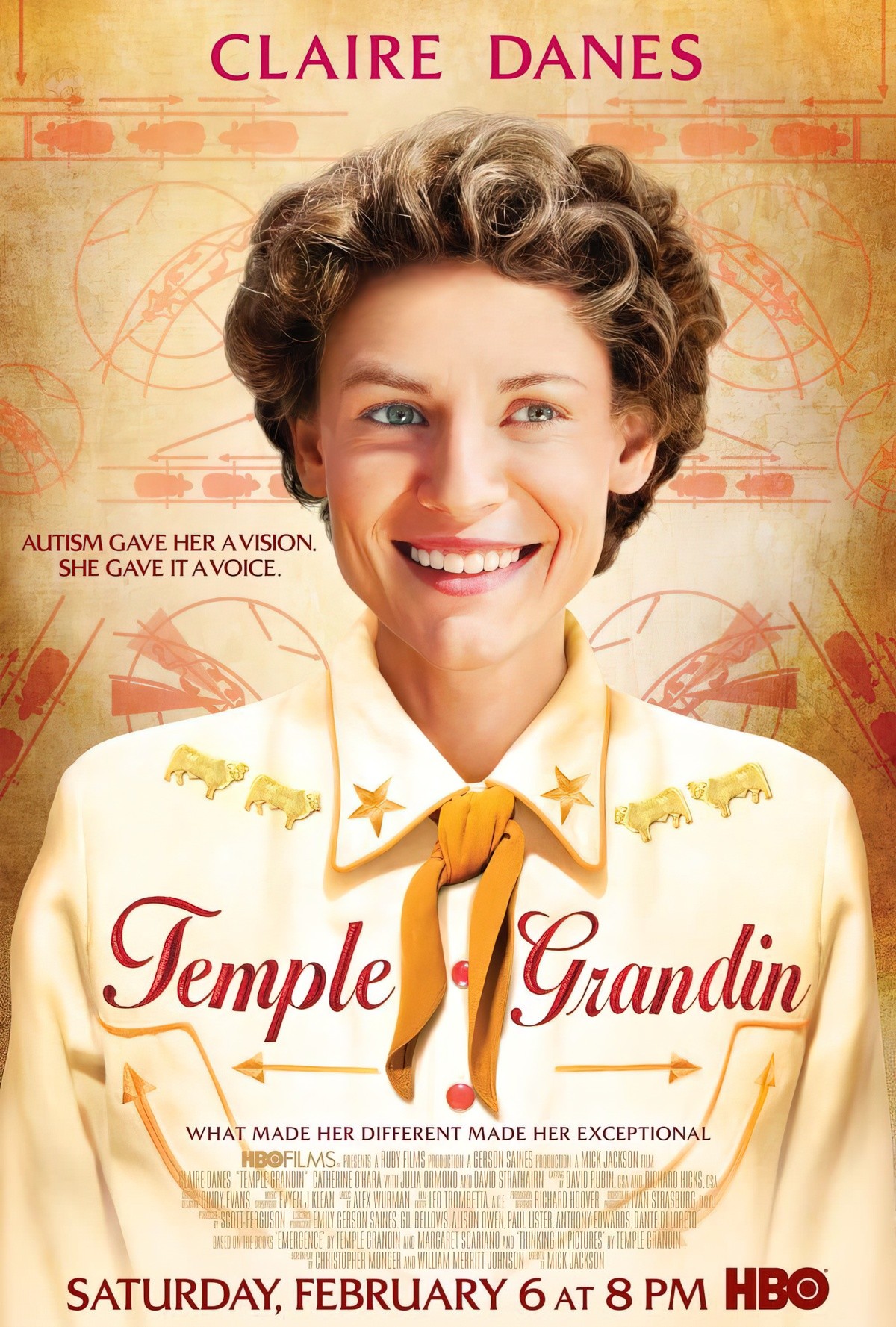

I recommend watching the biopic of Temple Grandin’s, who says this about the fortuitous timing of her birth:

I was fortunate to have been born in 1947. If I had been born 10 years later, my life as a person with autism would have been a lot different.

The Autistic Brain: Thinking Across the Spectrum

Grandin was also lucky to have a mother who didn’t trust what learned men were telling her. Grandin writes about how in this era, with autism being such a new diagnosis, mothers of autistic children were blamed for making their children autistic. It was presumed that mothers of autistic children were insufficiently loving and warm, hence the terrible term, ‘refrigerator mother’.

One person responsible for this mother blame was a man called Bruno Bettelheim (who was also influential in the field of children’s literature).

Shirley Jackson was herself a parent. In fact she had four of them. So she was an experienced mother.

They had four children, Laurence (Laurie), Joanne (Jannie), Sarah (Sally), and Barry, who later achieved their own brand of literary fame as fictionalized versions of themselves in their mother’s short stories.

Shirley Jackson Wikipedia article

Obviously, Shirley Jackson’s eldest son gets to star in “Charles”. Rather than speculate about whether or not Laurie was a gifted fabulist (as I was at that age, I must confess), it’s more interesting to consider Shirley Jackson’s astute insight into parenting culture of the era. I have no doubt that Shirley Jackson would have found the ‘school gate’ culture of mothering disturbing. I imagine Jackson looking on as other parents, probably mothers, discuss someone’s poorly behaved child, and assume with no evidence whatsoever, that:

- whatever is relayed to them via their own five-year-olds is the truth

- that whatever behavioural problems exist are entirely the mother’s fault.

“Charles” is therefore a didactic story: Don’t trust what young kids tell you. Their imaginations are too powerful. Don’t gang up on mothers. That mother could just as easily be you and, after all, no one’s kid is perfect. If you are a mother, and you have enough children, that mother will one day be you.

However, like the very best didacticism, Jackson achieves this end via the technique of subversion. She first encourages readers to judge the mother of Charles, then pulls the rug out from under our feet, encouraging readers to judge our own preconceived ideas about reasons behind a ‘badly behaved child’.

Shirley Jackson was prophetic in her refusal to blame a mother for a child’s bad behaviour. We now know much more about neurodiversity and neurodivergence. In fact, we have learned more in the last 10 years than in the last 100. The new mantra, replacing the terrible one about the rod: “All behaviour is communication.”

COMPARE AND CONTRAST

“The People Across The Canyon” by Margaret Millar is less well-known, but if you enjoyed “Charles” by Shirley Jackson, definitely check that one out.