If you’ve ever wondered about the difference between chapter books and middle grade books, or picture books and chapter books, you’re in luck.

RESOURCES

Kate De Goldi talks to Kim Hill on RNZ Saturday Morning With Kim Hill and makes a very good job of explaining what makes the ‘Chapter Book’ a separate category in the world of children’s literature.

The notes below also come from Writing Blueprints webinar. (Starts after 11 minutes)

Chapter books are better able to be defined than other types of books because they are for quite a narrow developmental process so you can say certain things about what most children will be capable of when introduced to chapter books.

The reading progression: Picture books, more complex picture books, chapter books, novels.

Chapter books are ideal for building confidence in reading without help.

Walker Books have been fantastic in how they publish and pitch chapter books at the right age.

FEATURES OF CHAPTER BOOKS

They’re not readers that you’re learning to read on — they’re a different thing again, because they have a carefully calibrated vocabulary. This is not what’s happening in chapter books. Chapter books have a wider vocabulary. Different authors explore the width of that vocabulary in different ways.

Chapter books have a sustained narrative. You also get episodic stories, such as Milly Molly Mandy.

They can be read to the child, or the child may read chapter books themselves. Both.

There is a certain simplicity about chapter books, and a certain ambit (scope) in the storytelling. The readers are now entering the wider world, so characters in chapter books include people you meet at school and out-and-about. But it’s also a period in a child’s life where friendships are developing and readers are learning to co-operate. Children in chapter books tend to have more agency than they might have in a picturebook (bearing in mind there is a huge range of picturebooks out there now), but in a chapter book the main character does not have complete agency because they are 6, 7, 8, 9 years old. So the progress of a story can be aided by the child’s agency but also with assistance of someone else, even though this assisting character is often another child.

They’re often school stories/family life/holidays, and there will be a problem to be explored, maybe something to do with dealing with things in the world, or something stopping the child from having they really desire etc. There is often an animal that is important in the child’s life.

Chapter books often feature black and white or colour illustrations.

Text is written in short paragraphs. Plots are clear, simple and fast-paced. Strong narrative drive. Lots of dialogue.

One major aim is to make the young reader feel accomplished so they go on to read more books.

Most readers are 6-9 but the entire range of chapter books can serve readers from 5 to 10.

Early chapter books

Early chapter books are also called transition books are for younger readers 5-8. Or perhaps the parent is reading them to a 4 year old. 2500 to 7000 words long. Chapters are 500 words or less. Colour illustrations fill up a lot of these books. There’s a lot of space for the reader’s imagination. Unlike in a picture book, the illustrations aren’t really going to add information to the story that isn’t apparent in the text. (Low ironic distance between the text and picture.) The reason being, the reader is going to look to the illustration to help them decode the words. e.g. The Princess In Black. Illustrations and text support each other. The Kingdom of Wrenly is another excellent example of an early chapter book. Early chapter books are written at about the second grade reading level but some children in first grade can also read them.

At the end of the early chapter book category the illustrations are a bit fewer and tend to be black and white. With Eerie Elementary there are 96 book pages, 6000 words. (When you write it yourself it won’t be 96 pp long — this is including the illustrations.) This series from Scholastic has a bit of a spooky feeling. It includes friendship dynamics.

OLDER CHAPTER BOOKS

Older/later chapter books are for 7-10 year old readers, sometimes all the way up to Year 4. Texts are 7000 to 12000 words. Generally black and white illustrations, not necessarily on every page. “Spot illustrations” — mostly text with a little picture. Clementine by Sara Pennypacker is an older chapter book. Lots of depth in terms of character but not complication in terms of plot. Ivy + Bean is about 120 book pages, 8000 words. These girls have a wonderful dynamic on the page. They go on very minor but delightful adventures. They tend to have slightly larger than spot illustrations. The pictures might add a bit of extra information, telling a secret, but it’s not carrying the plot. Lots of dialogue, conveying lots of story in a really fast way. 12000 is the upper limit but quite long for a chapter book. The Time Warp Trio: Your Mother Was a Neanderthal by Jon Scieskzka is 80 book pages, 10,500 words. There’s a trio, a time warp. 8 year olds are interested in time warps and Pokemon and similar. Lots of text, one small illustration which adds story movement/humour. A child isn’t getting frustrated trying to picture something before moving along with the story. This book has excellent dialogue. There are three boys and everybody’s dialogue sounds different.

Every publisher classifies chapter books slightly differently. There’s some crossover in ages. Countries also do it differently. The story itself will determine what kind of chapter book it is. If mainly action and dialogue it’s probably an earlier chapter book. If it shows some of the protagonist’s internal thoughts and feelings or has a strong secondary character central to the plot it’s probably a later chapter book.

They can have interesting, creative, super fun formats. Graphic novels, a mixture of graphic novel and text on a page (Captain Underpants).

Certain subject matter crops up time and again in chapter books. For example, a character sees a ghost becomes the main plot of Owl Diaries: Eva Sees A Ghost and Ivy + Bean And The Ghost That Had To Go.

Young readers fall in love with characters which explains why chapter books are published in series. They tend to tell their friends about their favourite books.

Characters can be kids, animals, adults or anything else you can think of.

Humour is key.

There’s not much interiority in chapter books compared to young adult and adult books.

Chapters in chapter books tend to be titled. (Maybe this is partly why — or because — they’re called chapter books?) That appears in the table of contents.

Either present tense or past tense is used in chapter books.

How does a really good writer stitch together something with a very prescribed word length?

1600 word stories – heavily illustrated, though not as much as a picturebook. (e.g. Walker Shorts, Scholastic Branches.) Many chapter books are part of the Accelerated Reader assessment program used by schools to track students’ reading progress, which helps teachers, who are increasingly required to provide data to prove they can teach these days. Various different companies provide Accelerated Reader programs to countries around the world. (There are various opinions on the AR program.)

It’s probably slightly easier to get a chapter book published than other kinds of books because there are fewer being submitted, especially if it’s one of the earlier chapter books. Those earlier chapter books are perhaps not quite as fun to write, or maybe it’s just that an active knowledge of vocabulary usage is required, and this skill is not common. There are programs you can run your text through to give you the reading level of your book, like the function in MS Word, but these aren’t especially accurate. If you’re using lots of commas in a sentence you’ve probably got too much going on in that sentence.

Many chapter book authors make use of the Children’s Writer’s Word Book.

Is there a risk of being too formulaic? Yes, but in the hands of a really good writer, a fixed structure can be enormously liberating.

Anna Branford

Children’s author and maker of things (Melbourne based)

Published by Walker. Mostly English writers in the Walker series but also some Australian and New Zealand writers in this short series. 1500 words is almost too short. But Violet Mackerel is lovely, especially with the black and white drawings running all the way through. The pictures are an important part of the story, setting tone and mood. This book has a proper hard back and nice pages and feels like a proper, grown-up book. The story is perfectly paced, the relationship between Violet and her friend Rose is really nice.

De Goldi recommends Violet Mackerel for 6, 7, 8 year olds, girls probably. Of course there will be some boys that this appeals to but the stories are aimed at girls in every possible way. There’s a lot of gender division at this age.

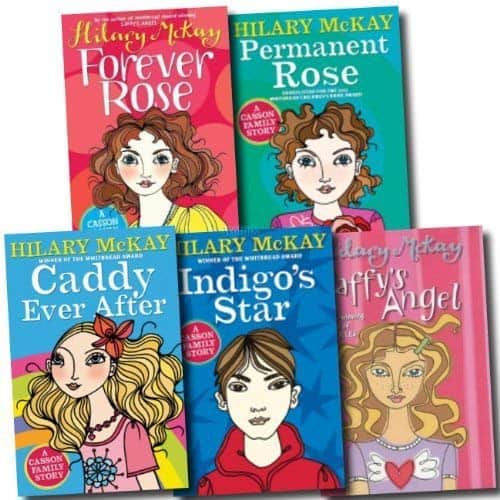

Hilary McKay

Almost 5000 words. Hilary McKay is a very good writer of middle grade and YA books.

Ursula Dubosarsky

Writer for children and young adults (Australian)

Boys would like this book. It’s got two guinea pigs. One of them is a policeman in Buenos Aires.

Sally Sutton

Annie Barrows

Writer for both children and adults (American)

Similar to Violet Mackerel, with black and white line drawings throughout but much more text.

As you may have noticed, Annie Barrows also makes stuff for adults (The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society, with Mary Ann Schaffer)

Amy Marie Stadelmann

Olive and Beatrix are twins, but they are very different from one another. Olive loves science, and Beatrix is a witch!

Best friends who are very different from each other make for popular chapter book dynamics, even though in real life it’s almost a rule that best friends in primary school have to pretend they’re they have the same interests. (Birds of a feather.)

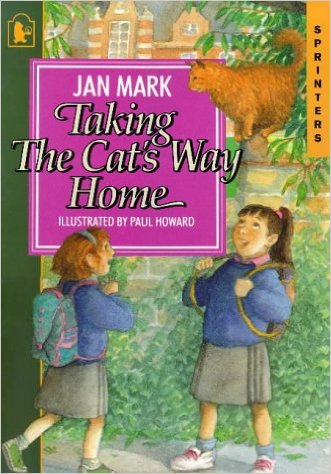

Jan Mark

Was a British writer

Jan Mark was very good at writing stories of about 2500 words. This is a masterly book to unpack from a writerly point of view. Five chapters, a very simple story about Jane and her cat Furlong. It deals with bullying. This story is very suburban, with a strong sense of place. What’s remarkable about it is the psychology of the characters, the plot, the resolution, the setting, all that is caught in 2500 words. Mark knows what to leave out and what to embellish. There is a pleasant old-fashioned feel to this, even though this book was written in the 90s.

So why does a book published in the 90s feel slightly old-fashioned? It might partly be to do with the regional accent and therefore the word choice, but this book is also written in the past tense from third person point of view. These books are almost always written in the third person — and there is a good reason for this. Take a slightly different kind of book like Diary of a Wimpy Kid, which is written in first person. Why aren’t books of this length written in first person? It must have something to do with the fact that the child hasn’t developed a strong sense of ego. Instead, they’re planted in a world where they’re part of a general sort of organism/community.

Perhaps this is happening less now, with first person fiction creeping down into this length chapter book now, and it seems we’ve entered a phase where the child must be the agent all the time. Individuals assert themselves even in quite early children’s fiction.

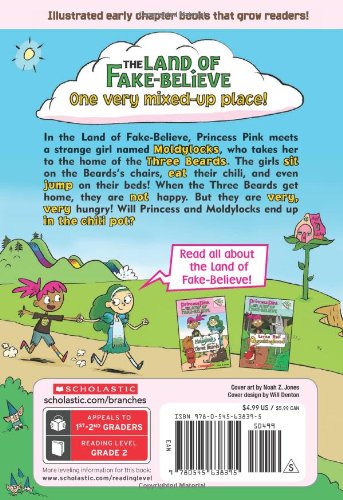

Noah Z. Jones

Jones writes for television and seems to have gotten started with illustration, later moving into both writing and illustrating his own stories.

Princess Pink And The Land Of Fake-Believe: Moldylocks and the Three Beards was both written and illustrated by Noah Z. Jones. The series is funny fractured fairy tales. The Princess Pink stories are part of Scholastic’s early chapter book line called Branches.

Plot of Moldylocks and the Three Beards

In the Land of Fake Believe, Princess meets a strange girl named Moldylocks. When Princess’s stomach grumbles, Moldylocks takes her to the home of the Three Beards. The girls sit in the Beards’ chairs, eat their chilli, and jump on their beds. The Three Beards are not happy when they get home—and they are very, very hungry! Will Moldylocks and Princess go into the chilli pot?

This book is about 80 book pages, 2,200 words. There’s a focus on repetition. Lots of illustration and fun and humour.

The main character’s main point is that she is despises pink, which I guess is meant to be ironic since her last name is Pink. However, Princess Pink’s hatred of anything associated with girls comes across to me as femme phobic, especially when you take a look at the thumbnail character sketch of Princess Pink which occurs at the beginning of every new book — in each story it is revealed that Princess Pink hates yet another girly thing.

Rebecca Elliott

Rebecca Elliott is the author and illustrator of Just Because, Mr Super Poopy Pants, Sometimes, and Zoo Girl, for which she was nominated for the 2012 Kate Greenaway Medal. She both writes and illustrates the Owl Diaries.

Owl Diaries is a chapter book series by Scholastic. This is another series in the Branches imprint.

It is written in diary format from the point of view a young owl girl, Eva Wingdale. She has a best friend called Lucy. Sue Clawson is the enemy. In her diary, Eva records all of her likes and dislikes, relationships with family and friends, and her daily routine, as well as her experience trying to plan a spring festival for her “owlementary school.” (Treetop Owlementary.) She has strong opinions and is thoroughly likeable. Puns and illustrations abound. Designed to appeal to girls ages 5 to 8.

In book #4, a new owl named Hailey starts in Eva’s class at school. Eva is always happy to meet new people, and she’s excited to make a new friend! But the new owl befriends Lucy instead of her. So Eva gets jealous. Lucy is Eva’s best friend! Will Eva lose her best friend? Or can Eva and Lucy BOTH make a new friend?

(I think in cover copy, the answer to a rhetorical question is always ‘yes’.)

There are two plot threads in this one.

Plot One: Eva’s class has started a newspaper. Eva is a reporter. Other classmates have other jobs for the paper.

Plot Two: Eva’s class will be welcoming a new owl, Hailey. Eva really, really, really, really wants Hailey to be her friend. In her mind, the two are already close friends. Eva makes her a welcome necklace and a special drawing—a map. But when her plan to change seats so that Hailey can sit by her backfires—Hailey chooses to sit in Eva’s old seat, the one by Lucy, Eva’s best-best friend, Eva is left confused and frustrated. No matter how hard she tries, Hailey is not becoming her best friend. And Lucy and Hailey are becoming closer and closer and closer. Eva finds herself alone but all is resolved in the end.

The life lesson is “never overlook your old friends when trying to make new friends. Adult gatekeepers love it when chapter books contain life lessons, which is a problem Ivy + Bean sometimes has because those two are sneaky little shits at times and go completely unpunished.

Don’t use animal characters to get out of more interesting things young readers might be interested in. This series is about owls, but actually they are girls. Bad Kitty is another series using animals as protagonists. The only thing to remember is that no matter the ‘skin’ of your protagonist, you have to do the work of character development.

Jane O’Connor

Fancy Nancy is a 2005 children’s picture book written by Jane O’Connor and illustrated by Robin Preiss Glasser.

Lauren Tarshis

The I Survived Series is also from Scholastic. This non-fiction series tells stories of young people and their resilience and strength in the midst of unimaginable disasters such as the September 11 attacks, the destruction of Pompeii, Hurricane Katrina, and the bombing of Pearl Harbour. She has to stay true and real but also has to tell a story.

These are good examples of how to keep a reader engaged, by bringing them into the scene.

Mary Pope Osborne

Magic Tree House series has been around for a long time.

The earlier ones are early chapter books but they get more complex and the later books are for older chapter book readers. The Merlin Missions are much later chapter books.