“Cat Skin” is a short story by Kelly Link, included in the collection My Mother She Killed Me, My Father He Ate Me, published 2010. Link says in her paragraph at the end of the tale that this is a brand new fairytale, based on on none in particular, but owes a debt to “Catskin“, “Donkeyskin” and “Rapunzel“. Link also acknowledges the influence of Angela Carter and Eudora Welty. I see similarities to Spirited Away.

CATSKIN THE ANCIENT TALE

“Catskin” is an ancient tale. If you’d like to hear “Catskin” read aloud, I recommend the retellings by Parcast’s Tales podcast series. (They have now moved over to Spotify.) These are ancient tales retold using contemporary English, complete with music and Foley effects. Some of these old tales are pretty hard to read, but the Tales podcast presents them in an easily digestible way. “Catskin” was published June 2019.

“Cat Skin” by Kelly Link is a trippy story and probably has many interpretations. This is what I get out of it, anyway.

WHAT HAPPENS IN “CATSKIN”

Like The Cat Returns, this is a story about the underworld of cat magic, in which cats are mysterious gangs who shapeshift and who knows what. “Catskin” opens with a description of cats who live in and around a witch’s house. Apart from many cats, the witch also has children, which she hasn’t birthed the usual way, but from a boil on her thigh, or from bits of old rubbish.

The witch puts children together as others put together a chess set, which is an interesting analogy and one I’ve heard to describe fairytale archetypes. G.K. Chesterton said that Aesop’s animals can be considered pieces of games in chess. (Farmer, man, boy, widow etc.) Aesop’s use of animals in this way expressed a rather cynical view of human nature which has been influential in stories ever since. Marina Warner said the same thing when writing about ogres:

Ogres are used as stock in his stories: the word orco or orca designates a character in the same fairytale shorthand as ‘king’ or ‘princess’ or ‘prince’. As with a chess piece, the naming prescribes a certain position on the narrative board, and narrows the possible moves.

No Go the Bogeyman, Marina Warner

Link takes features of the oral tradition and addresses the reader directly:

If you are looking for a happy ending in this story, then perhaps you should stop reading here and picture these children, these parents, their reunions.

Are you still reading?

This direct address marks the switch from iterative to singulative. We learn that the witch is dying. One of her powers is ‘snatching Time’. She snatches it from here and there. I feel this is a modern update on the classic fairytale. From what I’ve read, the really old fairytales (more than 150 years old, say) don’t play with time very much. But because of modern astrophysics (and since Einstein) we now know that Time is way trickier and ‘spookier’ (to use Einstein’s term) than any layperson could’ve imagined. Link utilises the weirdness of Time, capitalising it in the German way. As soon as Time can be manipulated, this leads us to a fatalistic view of events. Link intends for us to make that link (heh):

Once the question of this revenge had been settled to her satisfaction, the shape of it like a black ball of twine in her head, she began to divide up her estate between her three remaining children. […] She could see Flora’s life, flat as a map. Perhaps all mothers can see as far.

By the way, Link is inverting the usual gender of fairytales — it is usually Kings and Fathers who perform a deathbed division of their property in fairytales. The only way a woman can have any real power is by being a witch. So this witch has her own property, living like an outcast King.

The children are introduced:

- Flora with red hair (The witch favours red hair), a modern sort of woman who has been waiting for her mother to die. She inherits the automobile and a Magic Porridge Pot sort of purse which will never be empty so long as you leave a coin in the bottom.

- Jack, who can’t read but who inherits the books.

- Small, the youngest, who still sleeps in his mother’s bed but who is ‘not as young as you think’. I’m thinking of Pope from Animal Kingdom. Small is described in a feminine manner — he does the care of their ailing mother witch. But he is pragmatic about death. He asks only for the mother’s hairbrush, as Beauty asked only for a rose, and Aschenputtel asked onto for a hazel twig. A marker of fairytale virtue, or stupidity? We’re yet to find out.

The witch tells them the house will be of no use to any of them because without her in it, it will pine and grow sick. She created it long ago from a doll house, with a staircase that goes nowhere. The cats will know what to do with it, apparently.

The witch vomits up all sorts of things as she dies — things that aren’t edible, like she’s a human shaped trash heap. I’m reminded of No-Face from Spirited Away.

The witch dies and the children bury her in ‘one of her half-grown doll houses’. Small prepares her body for burial, and puts on every single one of her dresses. This layering seems significant — we each have many layers, different dependant on the day. While the children rig up her coffin, we get short paragraphs about what the cats are up to all this time. They’re agitated, coming in and out, getting sicker and sicker. They’re carrying Time, which is heavy. Time is treated as a concrete thing — they build nests out of it.

Flora and Jack flirt, which feels uncomfortably incestuous, because they were both ‘birthed’ from the witch. But they each speak of finding ‘their parents’, which suggests they’re not really related if they came from a witch. Flora and Jack drive off in the opposite direction their witch mother ordered. (They drive North — see The Symbolism of Cardinal Direction.) Small stays behind to look after the cats, even though the house looks frail and unwelcoming.

Jack sleeps outside with the cats, but finds they’re not good company. Still, they seem to be looking after him, making him a nest with their fur. One day he wakes up and sees a familiar-feeling cat. We know this is the reincarnation of the witch because the cat has red tufts and we’ve been told the witch favoured red. ‘”You may call me Mother,” she says.’ Link refers to this cat as ‘The Witch’s Revenge’ from here on.

The Witch’s Revenge says to burn down the house. This is a gruesome scene, as the witch’s cats have crowded inside. They’re burned, too.

More direct address — the reader is told not to do any of this. Direct address as cautionary tale.

The house won’t burn down but the windows melt down the walls. The Witch’s Revenge goes inside and comes back with a cat skin. It keeps coming back with more and each contains a lump of gold. I’m reminded more and more of No-Face from Spirited Away. This Revenge seems to be rewarding Small for small generosities such as brushing its fur, just as Chihiro was rewarded for basic civility at the bath house.

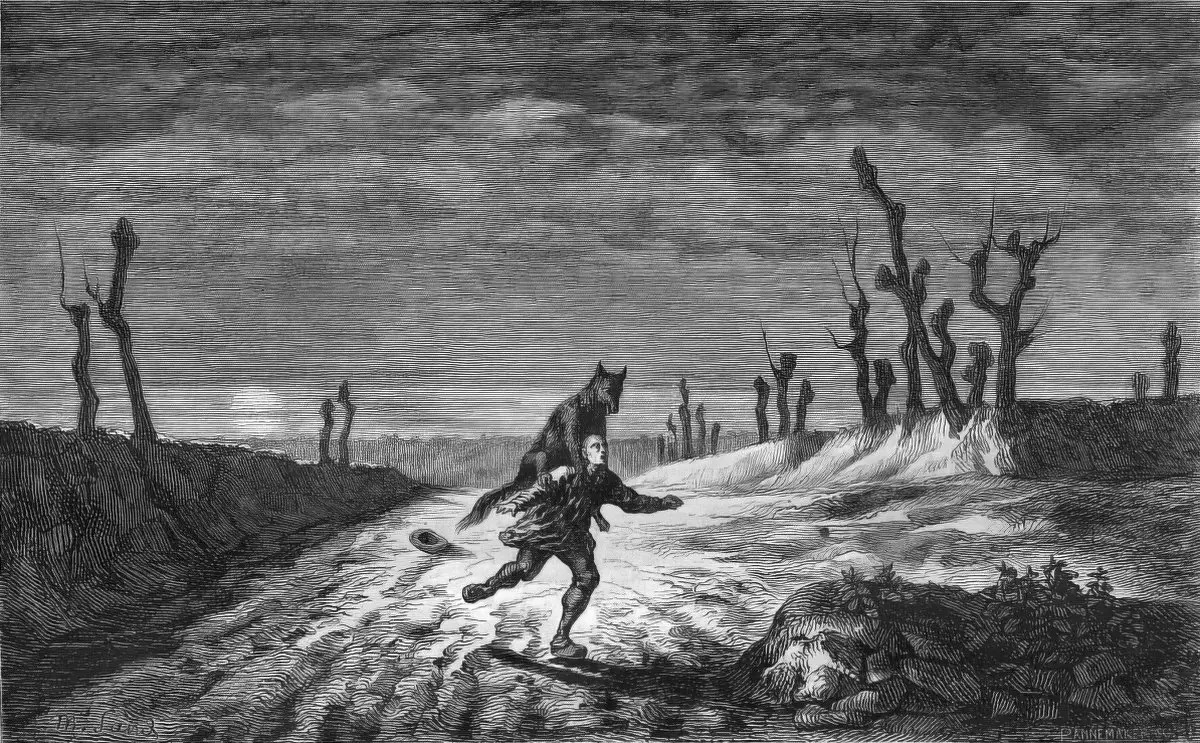

The Revenge digs up buttons and makes Small a suit out of cat skin. She tells him this bit of land where they sleep was once the site of a big struggle. Together they go into the forest, where a witch called Lack lives.

On the hells of Spirited Away, there’s environmental commentary in “Cat Skin” when Link tells us the forest is smaller than it used to be. It’s been encroached upon by human development. (Small is also growing bigger, metaphor for more powerful.)

Now we get the link to Rapunzel. The witch explains that people made houses to lock their children away. But instead of a tower, Link creates basements. Link takes a familiar expression, ‘house cat’ and invents super creepy etymology:

Now people mostly bury a cat when they build their house, instead of a child. That’s why we call cats house-cats.

The coat is still alive with cats, meowing. As they walk, Small is turning into a cat himself. They live like wild animals, drinking from streams, and at night they sleep in a catskin bag, which carries Time.

Small and the Revenge lift the lid on a small forest house and set whatever’s inside free. They can’t see it, but it arrives in Small’s dreams. He imagines it’s following them now.

We are introduced to Lack. Supernatural fairytale creatures tend to be strongly gendered in our minds — witches are female, wizards are the ‘male equivalent’. But in this story Lack is a male and also a witch. (Throughout Europe, a proportion of people burned at the stake were male — most often they were burned because they were associated with female ‘witches’ — so there will always be a gendered aspect to witches.) Lack is a bugaboo — he has stolen his children from their beds, apparently unable to make them himself out of bits and pieces, as can a female witch.

Revenge intends to live at Lack’s house. There’s been some history between them, but we’re told no one knows what it is. Presumably this is where Revenge will take her Revenge. She instructs Small to behave like a pet cat for Lack’s children.

There’s not much build up — like a cat pouncing out of nowhere, we’re told Revenge jumps at Lack’s throat and kills him.

The children scatter — some mean to go back to their homes. But exactly what became of them ‘Small never knew, and neither do I, and neither shall you,’ which is one way of tidying up a narrative.

It is revealed that the children are cat children. Turns out Revenge is annoyed that children with mothers and fathers have been stolen. She intends to return them, but this is not a true desire, because we’re told she doesn’t care if she returns the right cats to the right parents. When she returns, she accuses Small of having sex with the female child of Lack. Revenge makes a cat toy which is more of a trap — the remaining cats are made to run along behind, chasing it, as they leave Lack’s house.

The house is made of shit, which burns slowly. So although Small set it on fire it may be there still, we are told. Notice the present tense passages between the past tense ones — the present tense points to the universal, the never-ending nature of the story.

There’s a summary which spans years of Small’s life, living with Revenge in a room rented off a butcher. The reader is left to imagine the form they take, because surely cats can’t rent rooms from butchers. They keep cats in cages, though Small takes them out for walks. One day he comes home to find one of the three cats gone. He is told it escaped through the window and a crow carried her off.

Then Flora and Jack — destitute now — arrive on the doorstep of their new house. It seems the witch’s children are forever children, but adult in some ways. They’ve fallen out of love with other creatures and so on. It’s as if they’ve lived full, adult lives, yet here they are, once again the witch’s children. Only Small does not grow up, which I guess is why Link called him Small. He goes to school every day on a bicycle. (He’s large, apparently, which means he doesn’t need friends.)

Small’s adult fur begins to grow in — puberty, of course. The story gets really trippy now and I have trouble keeping track. This sequence, with the miniature naked prince and princess, and Small dreaming and screaming “I want my mother!” and the ants coming out of Revenge’s body remind me of the Battle sequence in a carnivalesque picture book — the craziness comes to a head. Things start happening more quickly until nothing more crazy could possibly happen and then we’re at the story’s end.

Once he’s planned to live in the belly of a fish who has eaten his tiny shrunken self, we are told ‘This is the end of the story’. We get a kind of an epilogue without it called as such, in which we wear about The Princess Margaret. In a Charles Perrault kind of summary we are told something true about life as the author sees it: ‘There is no such thing as witches, and there is no such thing as cats, either, only people dressed up in catskin suits.’

This story seems to be telling us that appearances are deceptive, and not really that important, as they don’t speak to the essence of a character.

STORY STRUCTURE OF “CATSKIN”

To simplify it…

SHORTCOMING

Small’s shortcoming is that he is forever childlike, even after he grows bigger. He’s dependent on his mother, even after her death, when she reincarnates as a vengeful cat. Small is under her spell and must go with her on her travels.

DESIRE

Surface desire: Small isn’t comfortable with the cruelties exacted by the mother cat, so he does what he can to ameliorate the lives of people she touches.

Deep desire: His nurturing nature indicates that he wants to be mothered himself. This becomes clear as the story progresses, obviated only at the anagnorisis phase.

OPPONENT

Revenge, the reincarnated cat mother

PLAN

The magic in this story is of the fatalistic kind. Small is bound to go along with a cat who he sees as a mother figure. It’s Revenge who makes all the plans.

At some point in every story, the passive hero usually makes a firm plan of some kind. They ‘come into their own’. When he realises that the thing in the forest crawled inside him he starts having nightmares. He then, finally, demands his own mother. He knows the cat has taken her and demands his mother back.

BIG STRUGGLE

The ‘Battle‘ comprises the trippy in-and-out of bodies sequence where even size is variable, like something out of Alice’s Adventures In Wonderland.

ANAGNORISIS

Small has always wanted a mother, but is told eventually that he doesn’t have one, as the lullaby said (earlier in the story). The singer of that lullaby says she has no mother and nor did her mother have one and so on, far back into time.

NEW SITUATION

Small has shed his cat body but morphed into something different, inhabiting the insides of a fish.