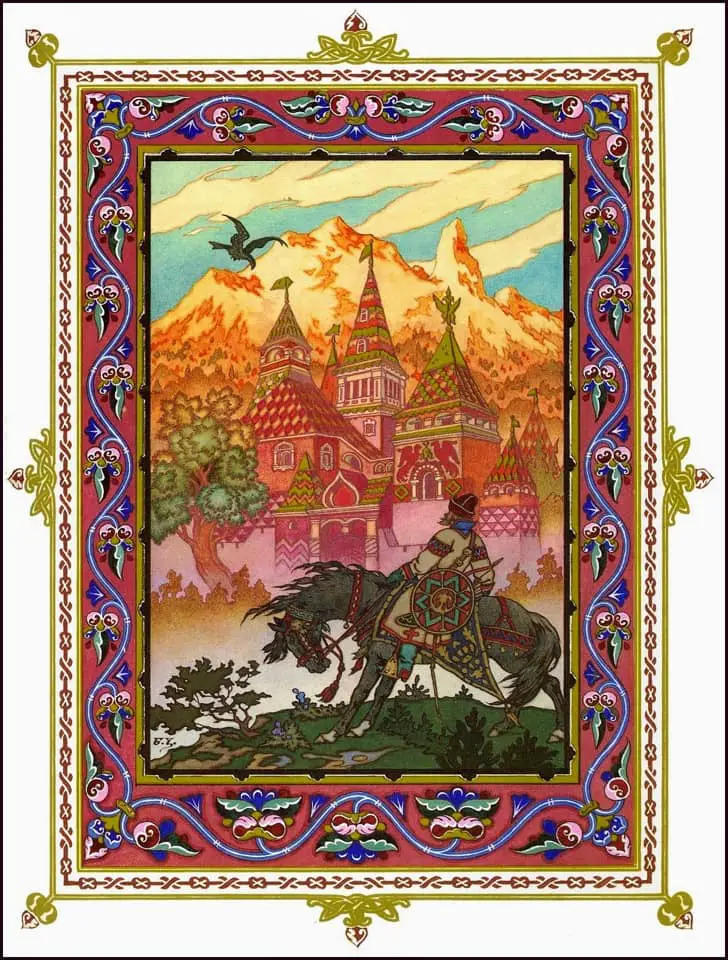

The castle is a feature of Gothic storytelling, and commonly makes appearances in ghost stories of all kinds. Dragons and castles also go together.

As kids my friends and I played King of the Castle. There’s not much to it. We used a pile of dirt, left by some builders. One person climbs to the top and says, “I’m the king of the castle, you’re the dirty rascal.” That’s about all that happens. The pleasure derives from pretending you’re the boss of your friends.

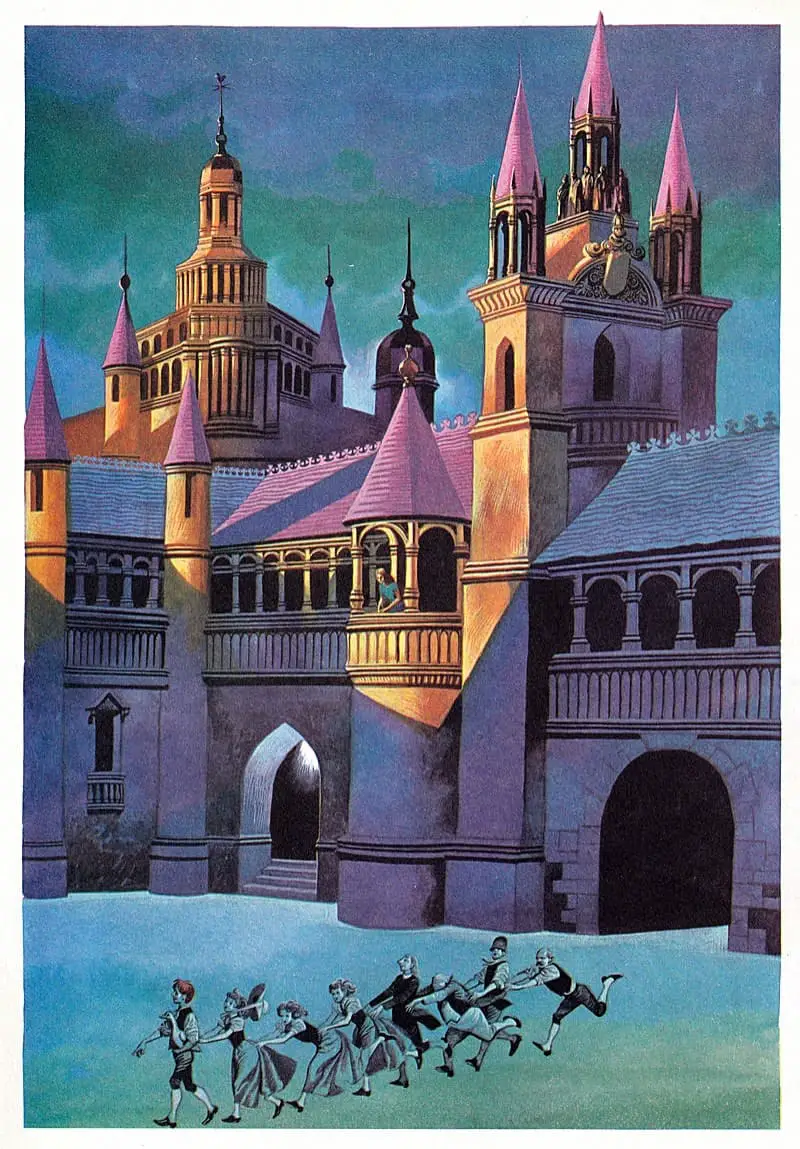

I wonder if kids still do this? The children in the painting below are using the elevated platform of a cart to play the same game.

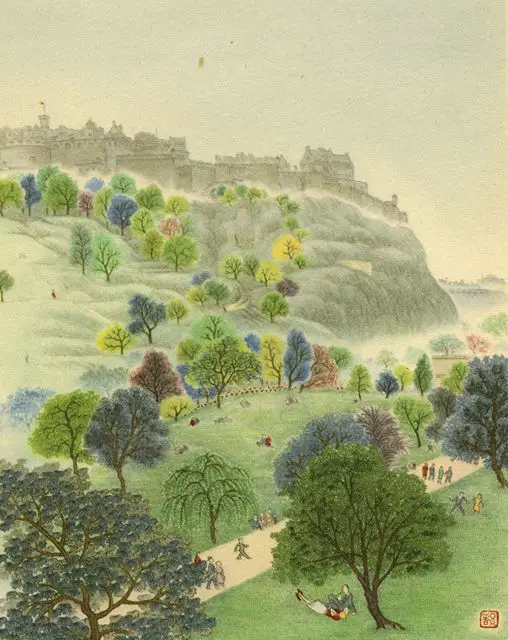

I stayed in a Scottish castle once, as part of a bus tour. The tour guides played the Ghostbusters theme tune as we rocked up, and regaled us with tales of ghosts and sleep paralysis. I don’t have any reason to believe in ghosts, so I don’t. I don’t believe in them.

But after dinner I went to find a toilet, which involved a labyrinthine trek through corridors, up and down stairs. I felt like every other visitor was downstairs in one of the expansive living areas. Eventually I heard something. It was the voice of a young girl singing, and in a language I didn’t recognise. That voice reverberating around the corridors and stairwells was ethereal. Such is the power of suggestion. A chill went down my spine.

We were probably sharing digs with a youth choir, who were using the corridors in which to practice, but that’s not what it felt like. For one five minute period, as I sat alone on a toilet in the middle of a Scottish castle, I felt like I’d heard a ghost. And I did go to bed, in a top bunk, wondering if I’d wake up in the middle of the night, unable to move, with two demonic eyes staring deep into my soul.

During that same year as on working holiday in the UK and Europe I visited numerous castles and one thing stood out: They are cold, stark, forbidding places. A modern heated house with a flush toilet provides a lifestyle magnitudes more comfortable than even the most lavish, princely life of the medieval and early modern eras.

SYMBOLISM OF THE CASTLE

The castle is a fortified place of safety which protects treasure or princess. The castle may be enchanted or bewitched, especially in the Gothic tradition.

MY HOME IS MY CASTLE

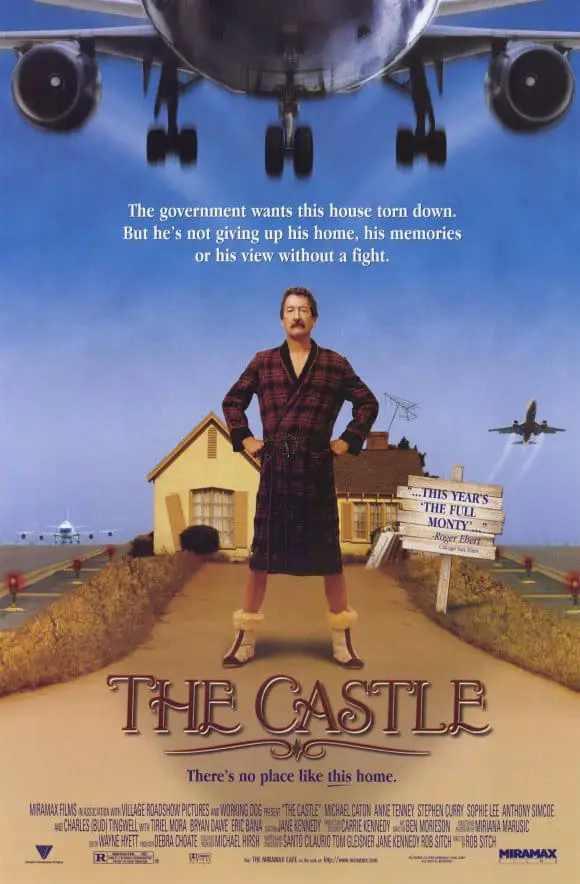

1997 Australian hit comedy The Castle is about one man’s fight to save his family home, which he believes is a beautiful establishment even though it’s right next to an airport runway, which wants to expand. Though ‘castle’ is used ironically, there’s something sweet about this family, who know better than most of us how to appreciate the small things in life.

As the real estate agent said, “Location, location, location”, and we’re right next door to the airport. It will be very convenient if we ever have to fly one day.

Darryl: [pointing at the verandah] See that lattice up there?

Valuer: Yeah?

Darryl: Fake. Plastic. Gives the place a Victoriana feel. Chimney? Fake too.

Valuer: Why’s it there?

Darryl: Charm. Adds a bit of charm.

The film offered plenty of quotable moments, and we use them frequently in this house:

This is going straight to the pool room.

“What da you call this darl?”

The Castle, 1997

“Chicken’’

Most people, at some point, want to make our domestic sphere as comfortable as possible.

The Dream Castle is basically the Dream House expanded in size and in emotion.

- The cellar/basement is the castle’s dungeon.

- The attic is the pinnacle.

- The perimeter fence is the stockade and moat

- The driveway and automatic garage door is the footbridge, accessible by lowered drawbridge.

- The child’s bedroom can feel like a keep if the child has been banished from the rest of the house.

- The hallway of a house has been demoted, but used to be an actual hall, still found in castles.

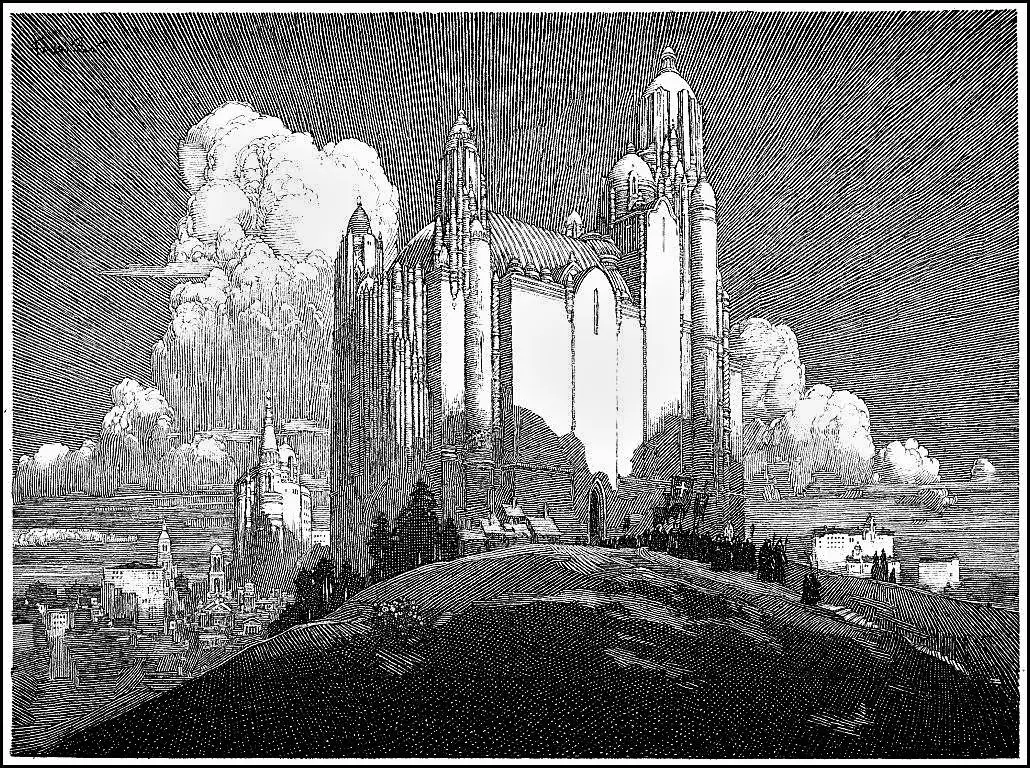

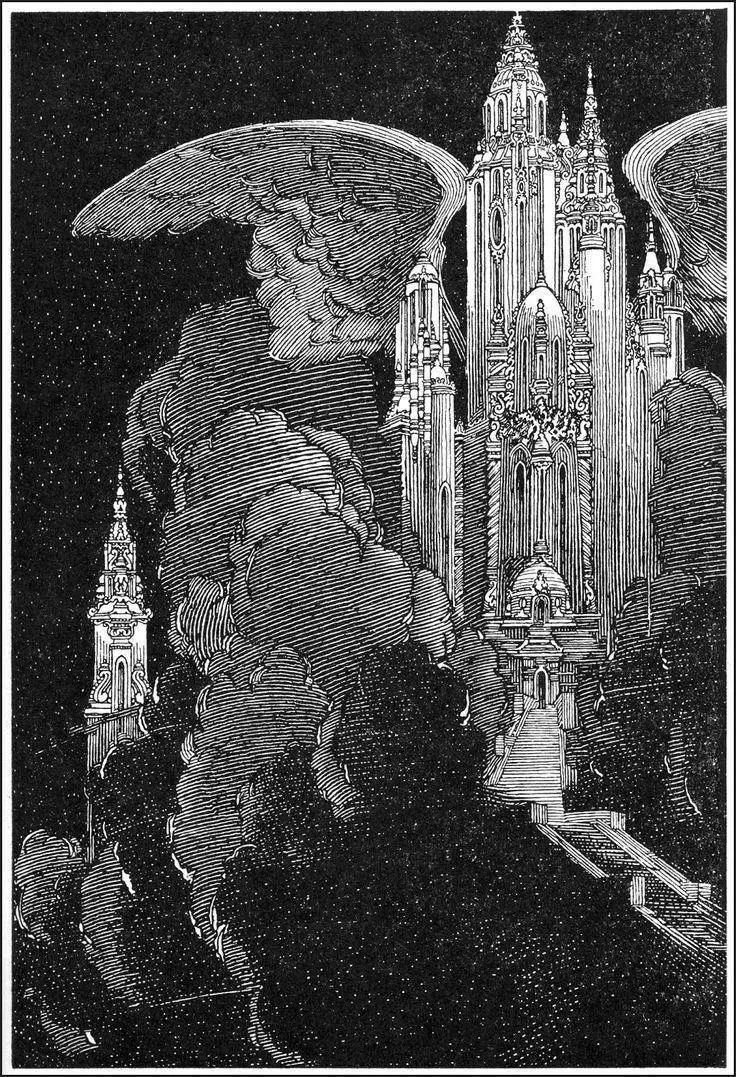

CASTLES IN THE SKY

CASTLES AND FAIRYTALES

Many cannibals have been ostracised from civilised society and live in the forest, but there’s another type of ‘ogre’ who lives in a castle. Jack and the Beanstalk is a good example of that kind.

WHAT WAS IT LIKE TO LIVE IN AN OLD ENGLISH CASTLE?

The following notes draw heavily from The English Heritage podcast, episode 59: What was life like at our castles?

However else we describe them, castles were first and foremost homes. Many things happened there but they were definitely lived in. Historians make use of surviving documents to learn about life in the old castles. Many of these are held at an archive in Kew, South of London. For people trained in Medieval Latin, Latin is the best language to read. Anglo-Norman is quite difficult to read for a modern French speaker, but the hardest language to read, even for a native English speaker, is English, because the spelling was so erratic.

What was it like to live in a castle? Apparently tour guides are asked this question a lot, but the short answer is: It very much depends which era you’re talking about. Also, every single castle is different, and life was different at each of them. The following English castles are examples of very different structures:

- Dover Castle in Kent: a medieval clifftop fortification with its great tower created by King Henry the second.

- Kenilworth Castle: first a fortress in Medieval times, later turned into a palace designed to impress Queen Elizabeth the first.

- Bolsover Castle in Derbyshire: a fairytale Stuart mansion designed to entertain its guests.

Castles first made an appearance after the Norman conquest.

When visiting an historic castle today, a tourist must make use of imaginative powers to envisage how it would’ve looked, sounded, smelled. They can seem gaunt and forbidding when no one has lived there for at least a few hundred years.

TYPES OF ENGLISH CASTLES

People have been studying castles intensively for a number of centuries. There are some broad categories.

- THE MOTTE AND BAILY CASTLE: The Normans had a man-made mound, surrounded by a ditch with some kind of tower on top of it, then a larger enclosed area at ground level, and this is called the bailey. A variation on the motte and bailey is the shell keep. Instead of having a timber or stone tower on top of the mound there’s a little curtain wall that runs around the edge of the top of the mound, with other buildings inside that e.g. Pickering Castle in Yorkshire.

- THE RING WORK CASTLE: This is another Norman castle but lesser known than the motte and bailey. This castle has no mound but the whole enclosure was surrounded by a ditch and bank, and some kind of perimeter defence, often a timber palisade or a stone wall.

- In the 12th century castles become more elaborate. There is now less use made of wood. The great castles are now made of stone. Keeps replaced the keeps and motte. In the 13th century the perimeter defences become more elaborate. The most elaborate form is found in the CONCENTRIC CASTLE, with more than one wall. The peak of defence sophistication happens in the late 13th century.

Surprising, perhaps, is how we know a lot about the architecture of castles but we know relatively little about who ran them. We think of them as properties of kings, queens and noblemen. These people were the owners, but they did a lot of traveling. There would have been long periods of time when they were not there.

We do know who would’ve been at the castles — paid officials. The top of that pyramid was called the constable of the castle, almost always a man. He was responsible for the upkeep of the buildings, but also the security of everything inside it. He looked after property, but he also ‘looked after’ any prisoners, which made castles part home, part prison, part torture chamber. We have surviving documents which show dealing with prisoners was often a large part of the constable’s job. “The constable is now entrusted with the safekeeping of this prisoner and will answer for him body for body.” If the prisoner escaped, or if something went wrong more generally, the constable copped it.

Some castles were forbidding, austere places, but others weren’t. Some royal castles (York, Dover, Carlisle) were places where the local arm of the royal state was responsible for governing that part of the country. People were brought to these places to be tried, imprisoned and executed. These places would’ve been quite grim.

But other castles, such as Kenilworth or Framlingham, were much more attractive once inside the forbidding exterior. These castles were big country houses.

They were an important part of the administration of the estate of a baron, but we know some of the owners would stay in them for weeks or months at a time. The castles would therefore have included all the comforts of home, well-furnished, elaborately decorated. The furniture would’ve travelled along with the travelling household, brought as luggage. They would’ve been staffed by a large and elaborate household who not only looked after the lord and lady, but also entertained guests.

Goodrich Castle from the late 13th century is a very well-documented castle, which is how historians know this. The other wealthy people came and stayed with the countess. She provided lavish feasts for her guests.

What hasn’t survived: The furniture, the paintings, the stained-glass windows, the hangings of textiles and some of the less substantial structures. We know all the men in a castle were riding horses and the ladies would’ve arrived in carriages. Therefore, we deduce the horses needed to be stabled somewhere and the carriages needed to be sheltered somewhere. Often those are the parts of a castle that have little trace, but they must have been there. Stables and shelters were a key part of operation of the site.

How many people would have lived in medieval castles such as Dover and Warkworth? This varied depending on circumstances, but the numbers of people living in these castles are probably fewer than we might imagine. Dover Castle is huge. We could house a lot of people in there. If we imagine a solder behind every battlement we have a cast of thousands. But in reality, there almost certainly weren’t many people there at all. Twenty of thirty seems like the magic number. We know this because of the documentation of Dover Castle called The Statutes of Dover, written sometime in the 13th century. That document tells us that at all times, especially at night, there shall be 20 watchmen on the castle walls. They would be circling the perimeter rather than stationed at any given garrison.

At Framlingham there were about the same number. At the end of the 13th century historians get quite a lot of documentation to work with because Edward the first was going to wars, building castles, and rebuilding a lot of the castles he already owned. He specified the number of men at each castle, which was about 30. They each had their own role.

What about women? They were certainly there. Documentation from a Welsh castle tells us that when there were 21 men at the castle there were also 7 women, 3 small boys and 4 infants. Some of the soldiers had their own families there as well, probably the officer classes. The constable, a knight, would have also had his own lady. She would have serving women to look after her. The same number again would’ve been around: grooms looking after the horses, the staff of the chapel (two or three chaplains plus a clerk). Not all inhabitants of a castle were armed and trained for fighting. 50 odd people would still be rattling around in a castle.

But at other times a castle housed many more people. For a castle like Dover or Carlisle, the enormous travelling circus of the royal household would pitch up there. Business or pleasure would take them there. In the 13th century the royal household is enormous, several hundred. They’ve all got to be lodged somewhere. So at odd moments, the castle goes from mostly empty to bursting at the seams. At the smaller castles, such as Peveril castle in Derbyshire, several hundred extras would multiply the inhabitants by five or six-fold. Where did they stay? Some of them were probably billeted at other places or perhaps they slept in tents.

When castles are fighting the castle is different again. Some people come to the castle arrive to defend it, drawn from the local area. Others may be taking refuge there. This all swells the numbers. Normally castles were sparsely inhabited; at times they were overflowing.

HIERARCHY OF PEOPLE AT AN ENGLISH CASTLE

This varies from castle to castle, but here’s a basic rundown.

BEGGARS: It was an important duty of a noble person or a king to be the patron of people low down.

LOWER DOWN SERVANTS: There’s a large and elaborate staff of low down servants. Sub-cooks e.g. the person in charge of the buttery (which leads to the ‘butler’), the man in charge of the pantry, responsible for bread, spices and other commodities. Someone else does work in the brew house, always associated with the bake house (same ingredients), someone looking after the cellars.

MIDDLE SERVANTS: For example the cook was fairly high up among the servants.

HIGHER UP SERVANTS: The chamberlain, the chaplains (doing administrative jobs). We think of chapels as being places of worship, but in the middle ages they were multi-purpose. This sits ill with modern conceptions. There’s documentation of a bill for the mending of the door of the chaplain, where the horse’s oats are kept. Keeping horse’s oats is not really compatible with the countess and her household attending religious services in the chapel, but when she wasn’t there they used the space as a lumber room. Sometimes weapons were stored in chapels. These were not sacred places set apart from everything else. Likewise, the people doing the jobs were a little more generalist than in later points in history.

THE HOUSEHOLD: The core of the travelling household, the owner. Everything revolves around them. Life would have been very different depending on whether they were there or not. After they departed the servants would’ve cleared out the garderobes (toilets) and other tasks. At the base of walls in castles you will see mysterious rectangular openings; these were the bottoms of the chutes that are underneath the latrines. From there it was easily shovelled out and spread around the fields or put into the ditch.

LANGUAGES SPOKEN AT ENGLISH CASTLES

In short, old English castles were multilingual places.

We might assume the higher the social status of the person, the more languages people could speak. But it works in reverse: The higher up the social hierarchy you sit, the better you can dictate whatever language you need other people to understand.

Of all the people living and working at castles, it was the servant class who were multilingual. They would have needed to understand at least basic instructions in the language used by the household. The English menial class in the 14th century needed fluency in French. Richard the second was the first King of England for whom English was a native language. Before that, the royalty and noblemen spoke French. Church services took place in Latin. Where language was written down, Latin was still the language of government and officialdom.

English was not the most important or widespread of any of the languages spoken in English castles.

SMELLS

One important smell was the smell of horses and their manure. Castles are associated with higher ranking people, who didn’t walk anywhere. They travelled in horse-drawn carriages or on horseback. Horses need a lot of grooming, shoeing and so on.

Castles would have also smelled of bread, and high end spices. There are no surviving recipes before the end of the 14th century, but we know the inhabitants of castles could get through prodigious amounts of food on days when they were allowed to eat it. (Roman Catholicism weren’t allowed to eat meat at certain times of the year or days of the week.)

Was the drinking water safe? Historians have traditionally said no, pointing to the great quantities of other kinds of drink consumed in castles. But they have more recently started to revise this opinion. The ale was not very high in alcohol (brewed with barley and wheat). They also drank wine, mead and cider.

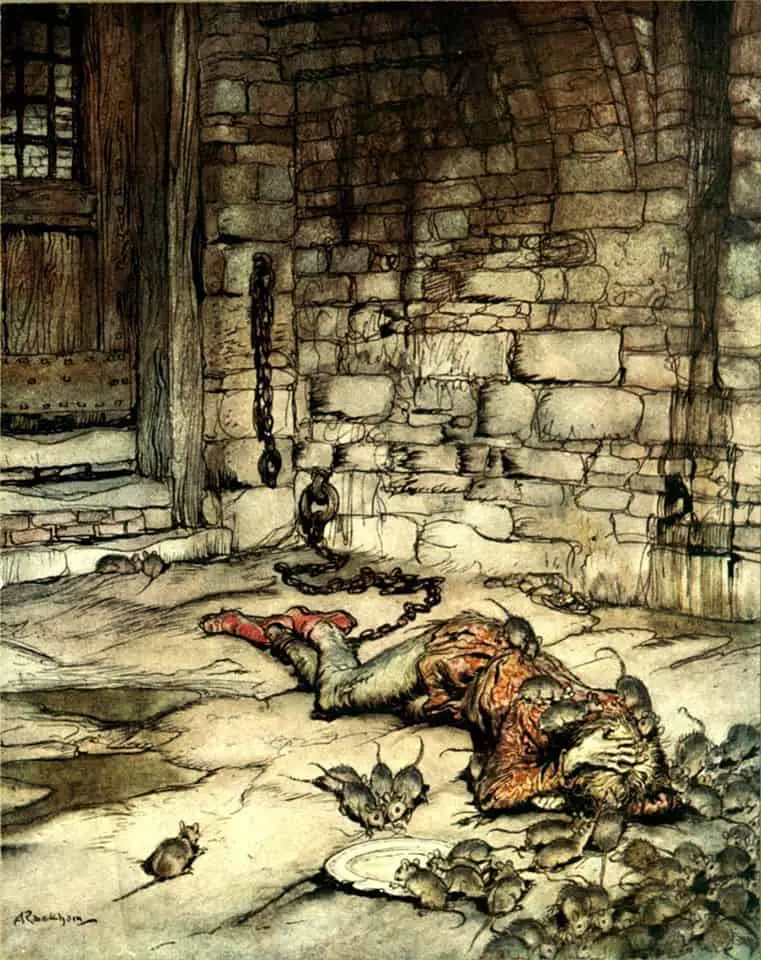

THE LIFE OF A CASTLE PRISONER

The most unlucky prisoners were indeed chained to castle walls. These people were thrown into poorly ventilated, unheated chambers. They often died. A modern misconception: Imprisonment wasn’t considered ‘the punishment’ in and of itself. The prison was where the constable shoved you while trying to work out what he was going to do with you longer term. People weren’t kept in prison for years at a time, and these dungeon-like spaces weren’t set up for any kind of habitation.

But many were political prisoners, who were people of importance, some of them royals. In these cases it would’ve been a bit like being under house arrest. They were given their own servants and ate quite well. They were able to warm themselves beside their own fire.

Pretty much anything in the middle ages could be considered a felony depending on who was in power. ‘Abjuring the realm’ was taking refuge by going into exile. Some got bored with exile, returned, were arrested, then brought into the castles for imprisonment.

Prisoners were probably kept in spaces otherwise used as store rooms or as accommodation for the garrison. Historians deduce this from graffiti on the walls. Some were kept in stables and sheds, because these places could be locked up.

MILITARY ACTION

Were castles designed for the good days (in peace) or for the bad days (for fighting and defence)? We still don’t know. The architecture contains many weaknesses, so they don’t seem particularly well-suited as fortresses. Historical documentation tells us that although castles would always be stored, it wasn’t always well maintained, with rusting, rotting leather and so on. This tells us that castle dwellers weren’t always at war. When they lived in times of peace they were relaxed enough to worry about their weapons.

But during war times everything changes. Rochester was involved in three sieges during the Middle Ages. During the Barons’ War, someone was writing down day-to-day expenditure while fighting was happening. Much of the expense was food and wine. In the margin there are notes which say ‘on this day they have attacked the castle’. When a siege was on, no one was going to the market to buy supplies. They were also getting through a lot of hay for the horses and wax for the candles. On Easter Sunday both sides of the battle had a truce and they all enjoyed Easter. They were all looking forward to eating meat after Lent. On the Monday, battle resumed. It lasted for about a week, until another army turned up from elsewhere. The attackers felt like they’d get stuck between the new guys and the guys inside, so left. (I see how the writers of Blackadder were inspired to write comedy out of English history, because real history sounds at times ridiculous.)

The castle with the most violent history would be Norham Castle, which is on the border between the heavily contested border between England and Scotland. At Dover Castle, sieges are a big deal, to do with foreign invasions of England or Civil Wars, but between those massive events, no fighting happening. Baronial castles and castles of bishops have no military history to speak of until the English civil wars of the 17th century. This can be considered a sign of the success of the castle; sufficiently intimidating castles aren’t going to be attacked.

Some sieges went on for weeks or months such as one battle at Kenilworth Castle, but most military engagements lasted a few days.

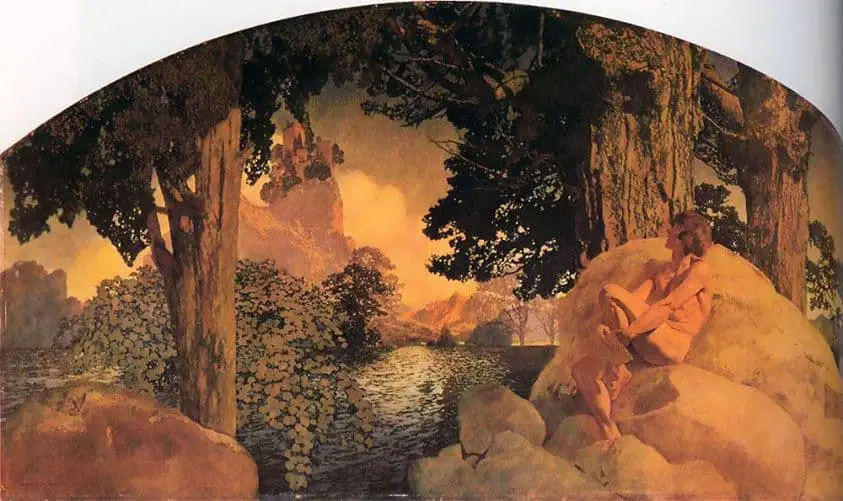

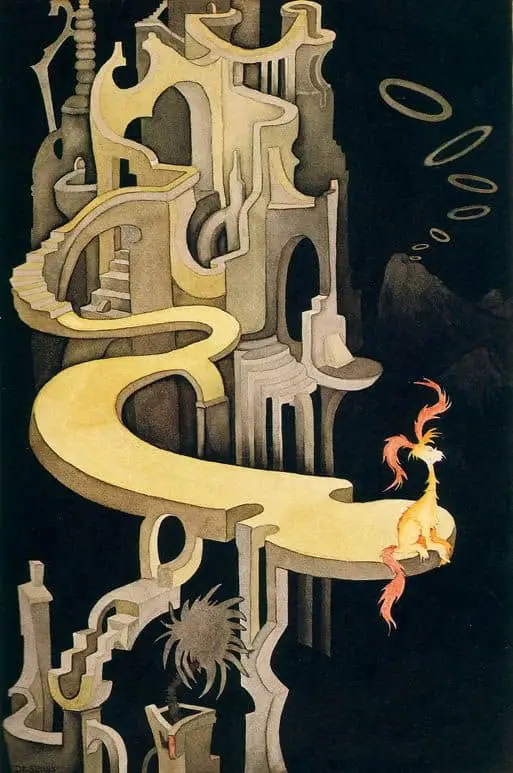

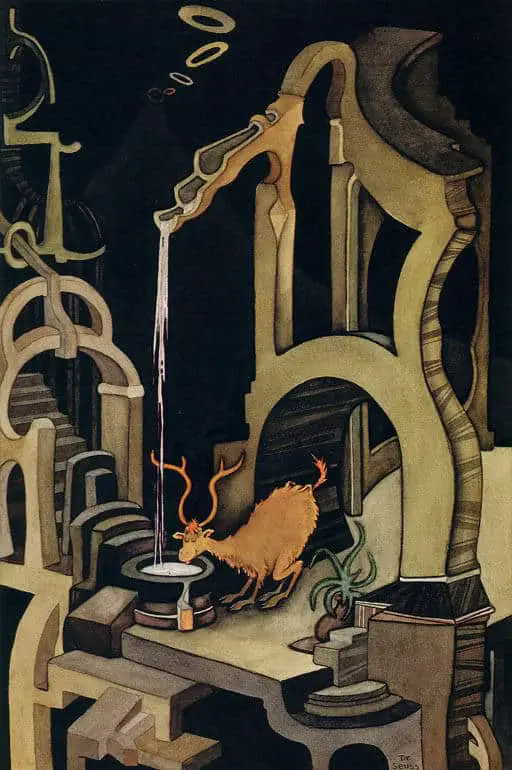

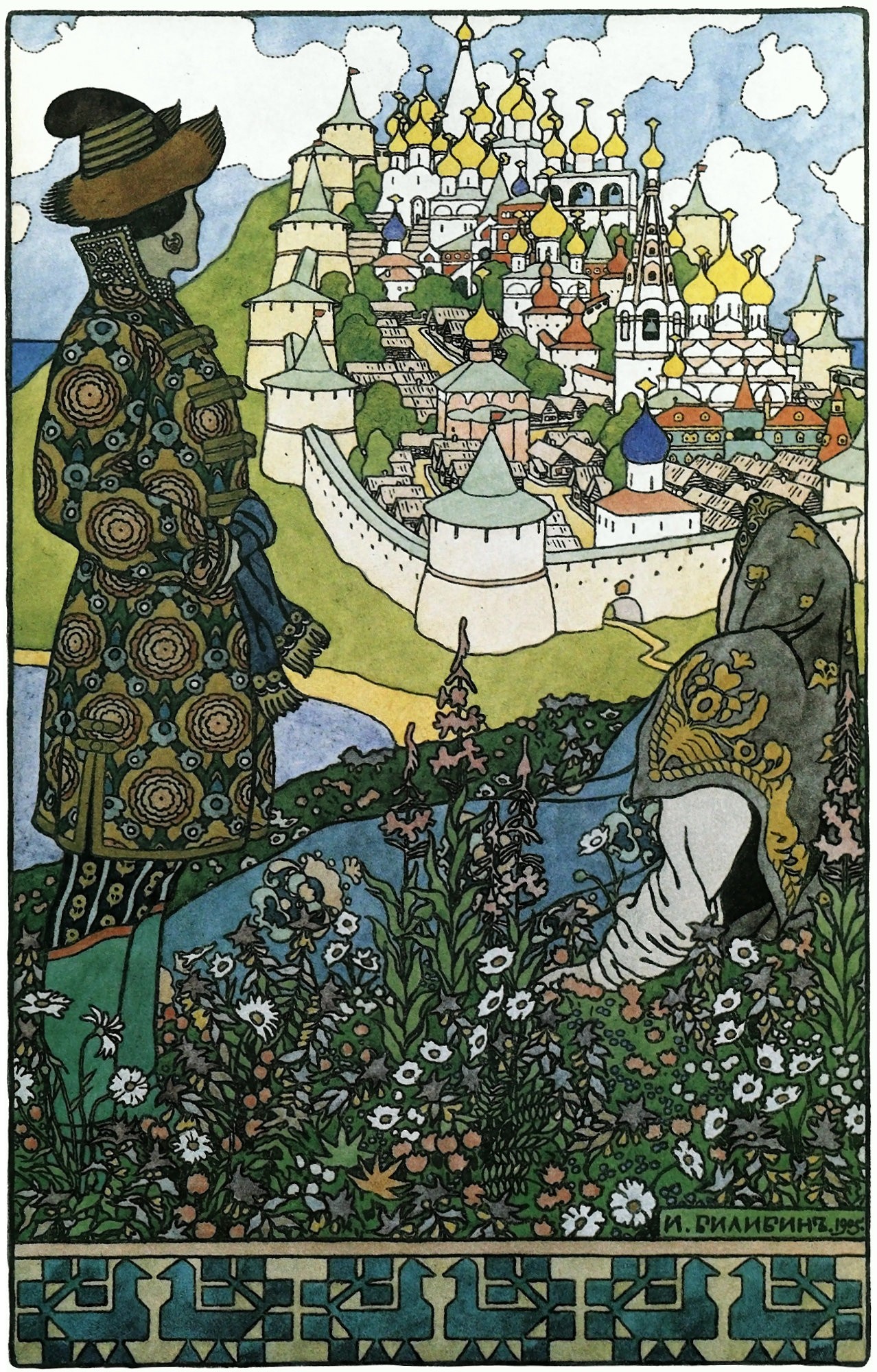

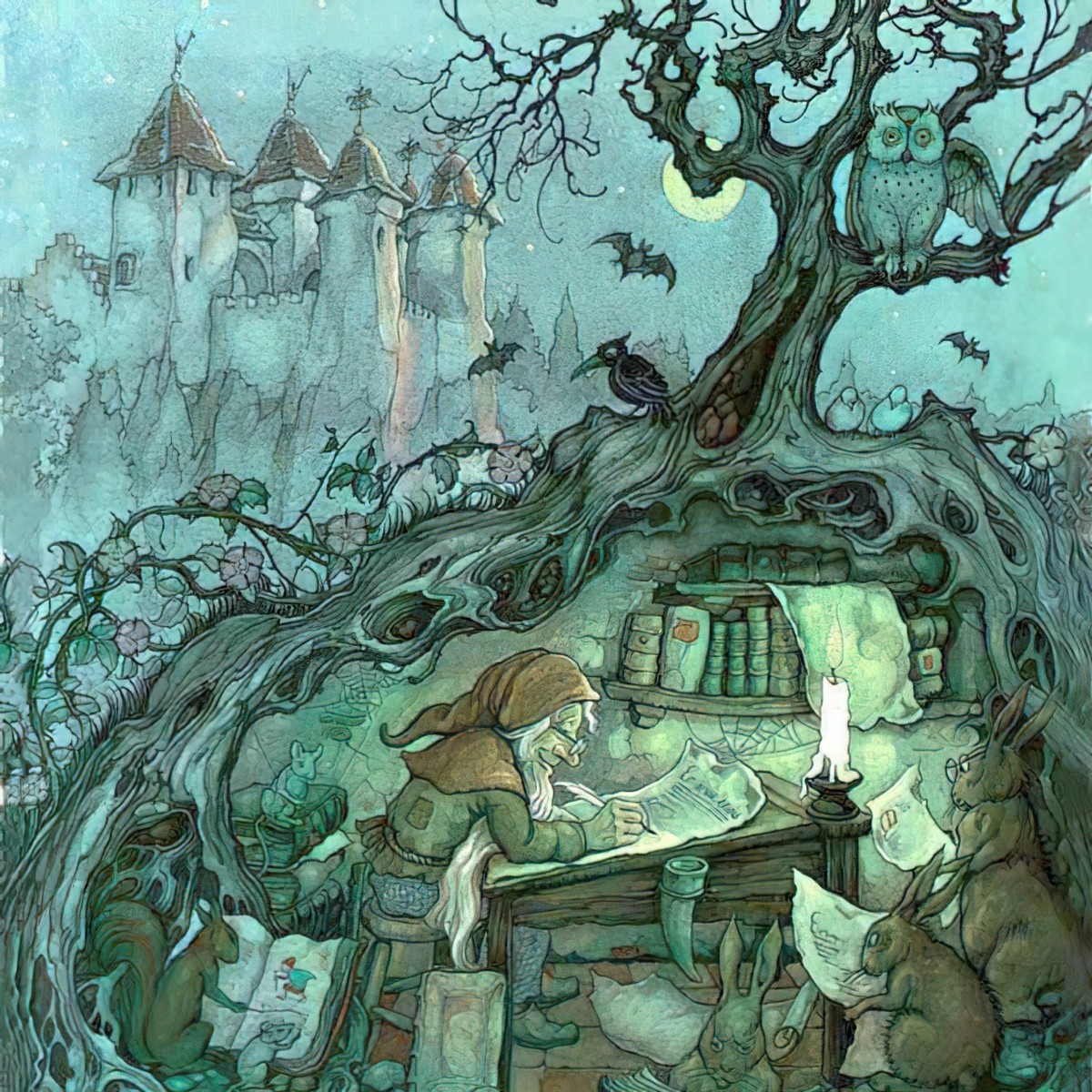

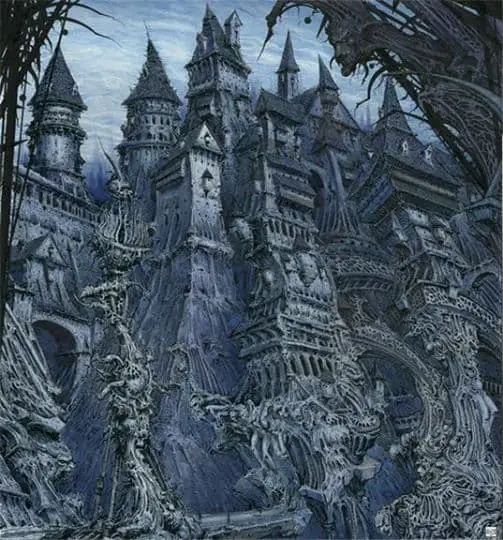

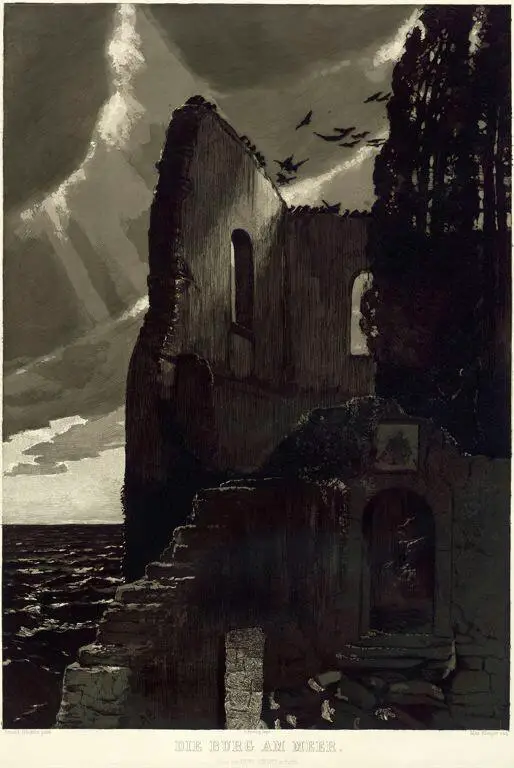

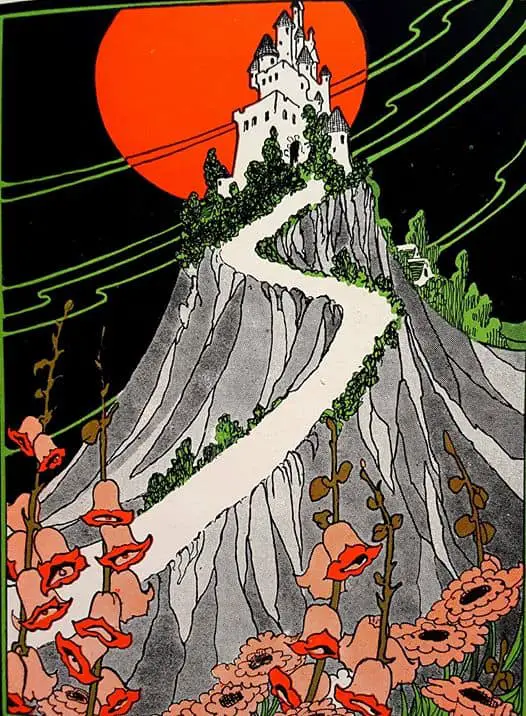

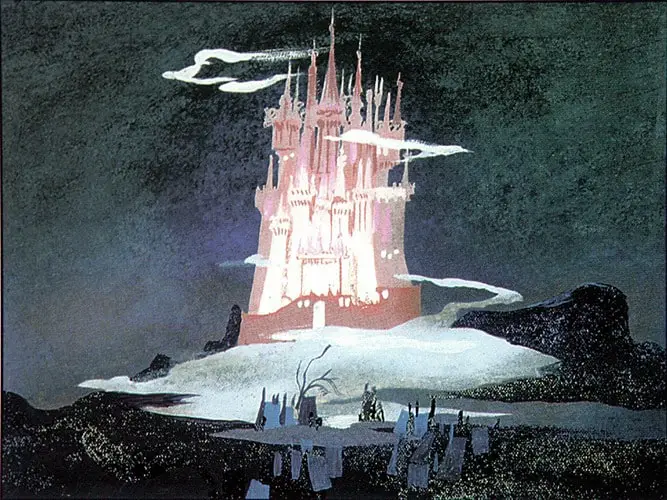

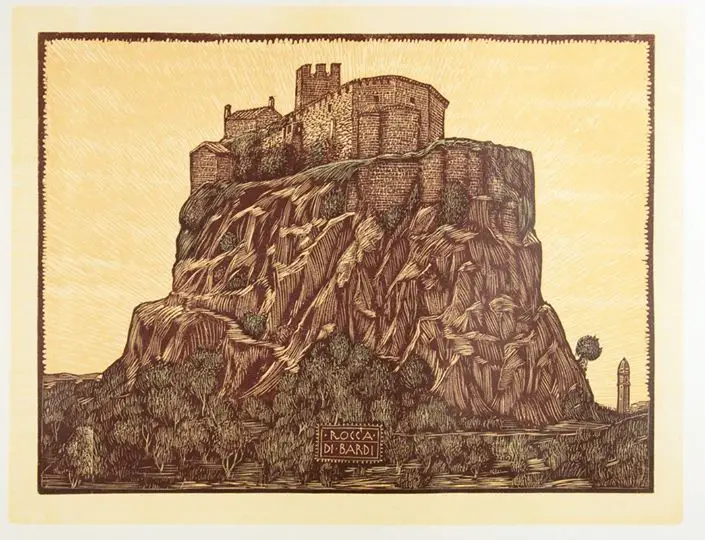

CASTLES IN ART

Reflecting the high variability of castles, whose owners pride themselves on ‘custom made’, artists over the years have envisioned many different impressive, imaginative dwellings.

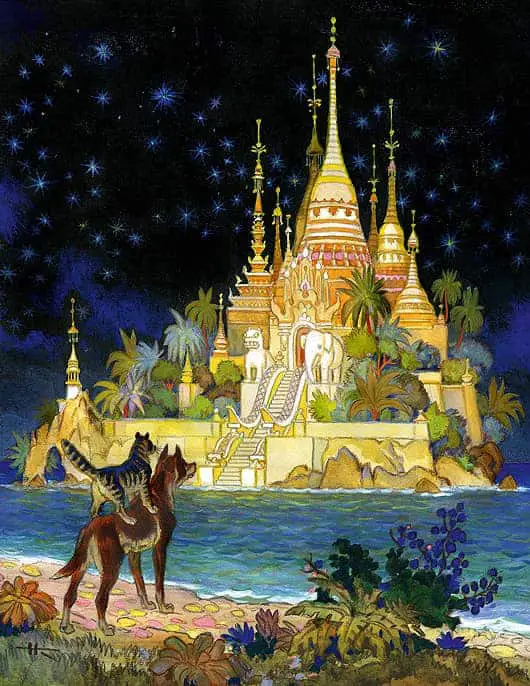

The castle is the historic narrative equivalent of the cold house made of glass frequently used in contemporary storytelling today. In these stories, a small, cosy, unassuming abode contrasts with a towering, austere, unwelcoming abode in the same arena. The castle backgrounded in the illustration below serves to magnify the cosiness of the dwarf’s underground dwelling.

SEE ALSO

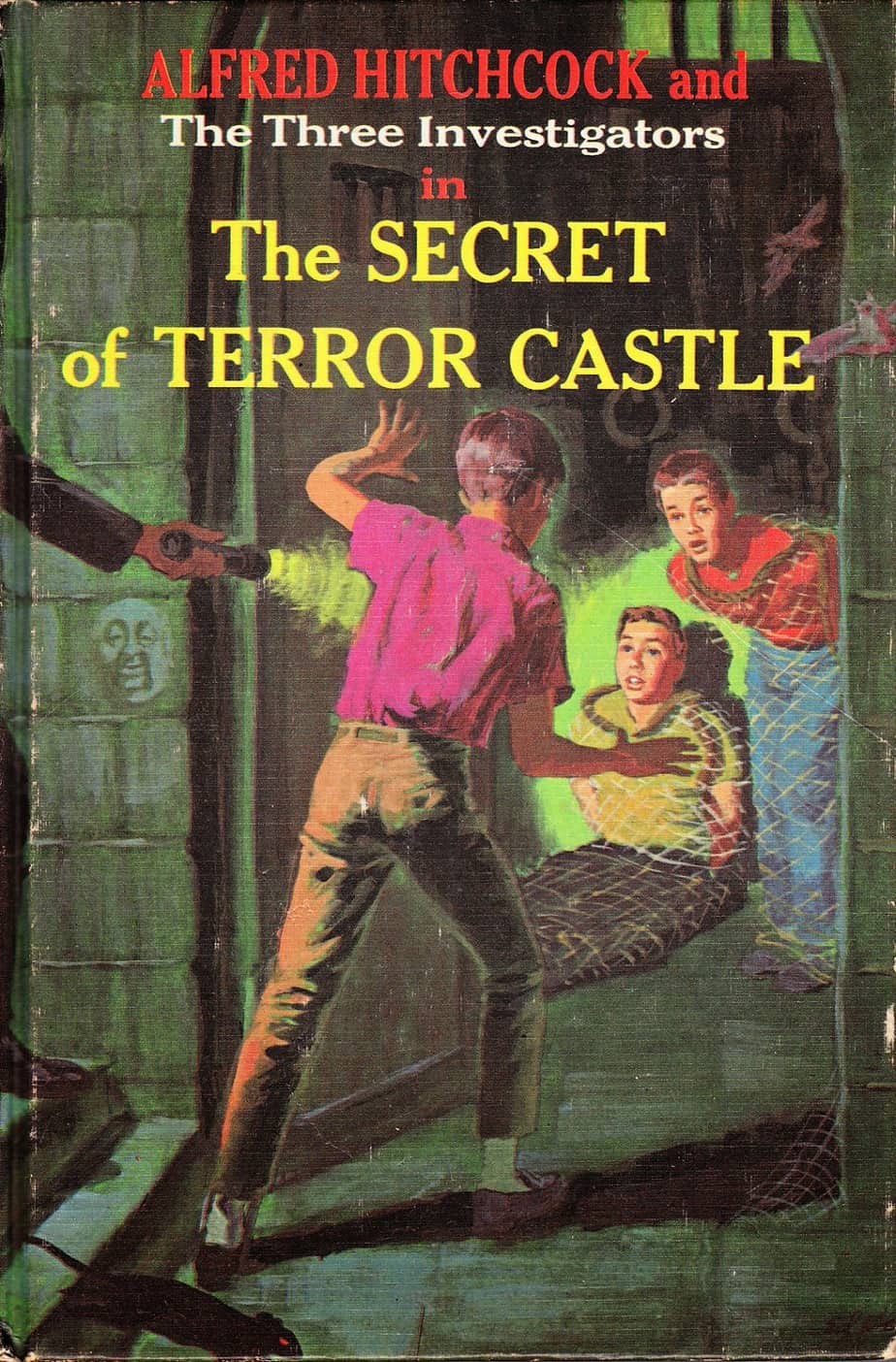

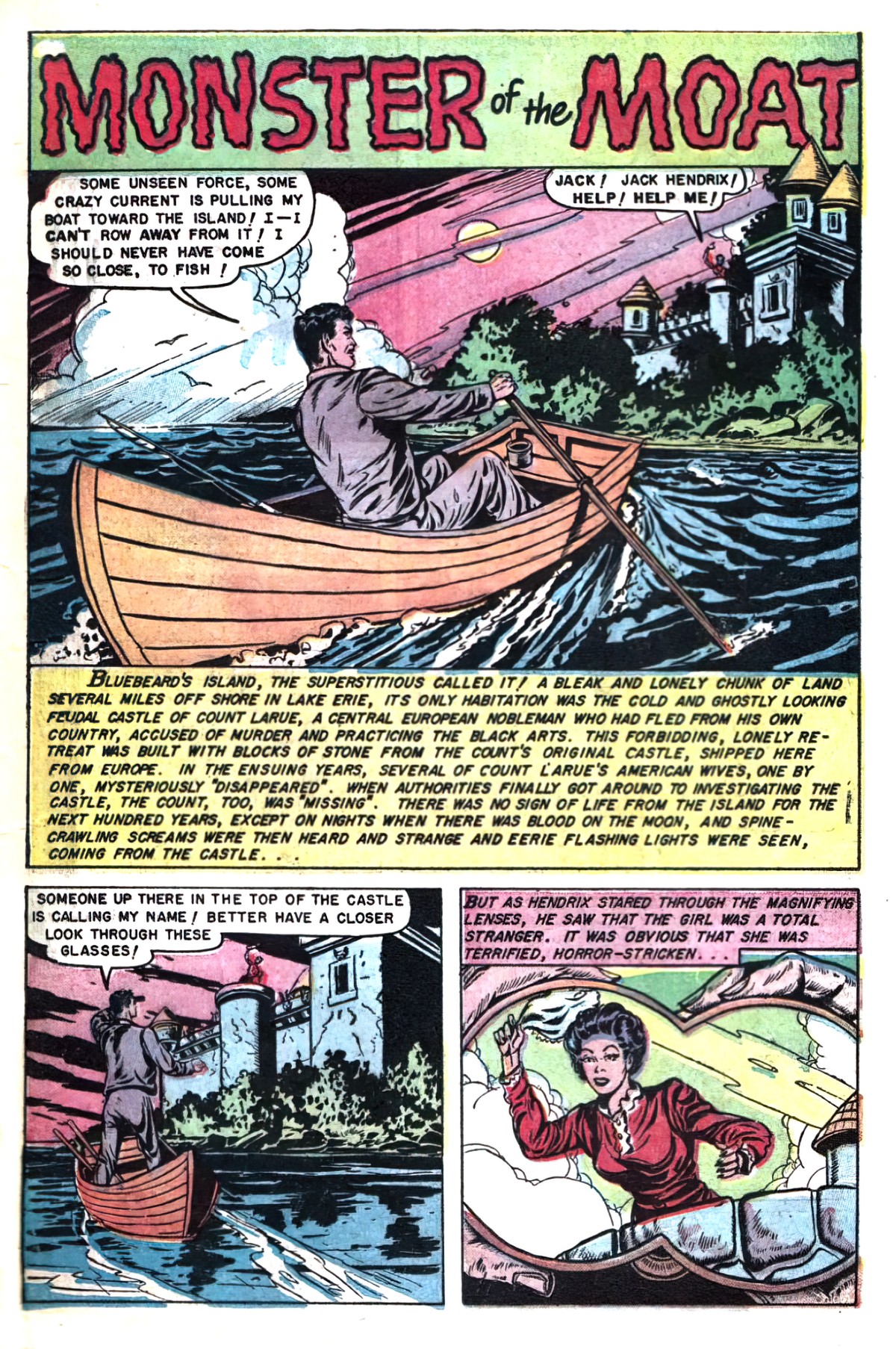

- The ultimate scary castle can be found in the Bluebeard category of fairytale. There is an entire category of pulp fiction inspired by Bluebeard plots, and the covers typically show a woman running away from a castle in the middle of the night.

- To The Manor Born Storytelling Technique

Heading painting: Maxfield Parrish – Dream Castle in the Sky