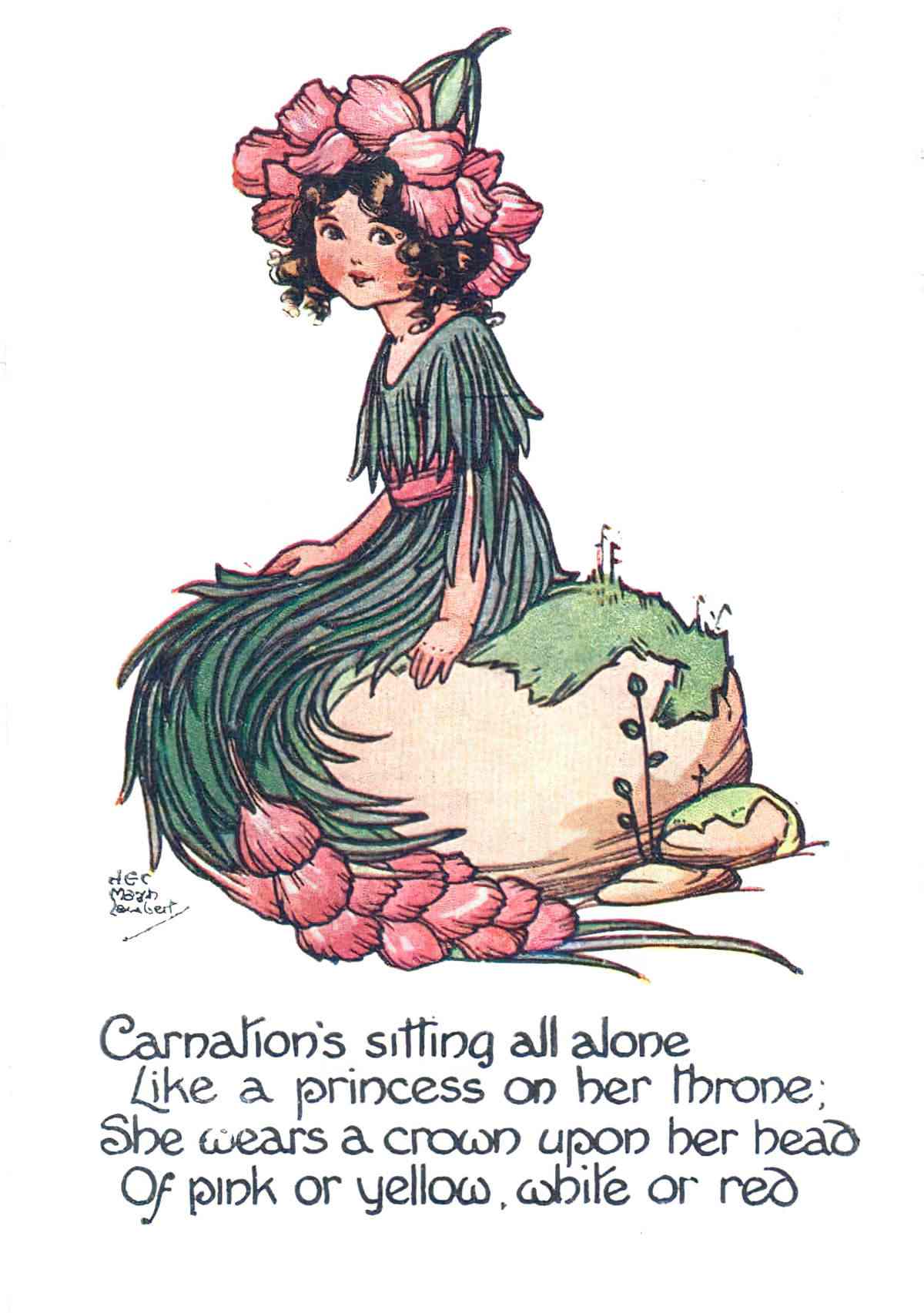

“Carnation” (1918) is a short story by Katherine Mansfield, included in her Something Childish collection. I like this one very much — a rare story of blossoming female friendship.

SETTING OF “CARNATION”

Mansfield often opens stories in medias res and grounds us in the setting:

On those hot days

The entire story takes place in a French classroom at a girl’s school on a hot summer’s day. In Mansfield’s stories characters are usually unable to comprehend much beyond their own personal world, however beautiful the natural surroundings and its ‘Stimmung’ (mood). The characters in this story are presented to us wholly within the classroom and its immediate surroundings. There’s no sense of anything existing off-stage.

“Carnation” is a standout example of Mansfield’s synaesthesic sensibilities.

Synaesthesia is a neurological trait or condition that results in a joining or merging of senses that aren’t normally connected. The stimulation of one sense causes an involuntary reaction in one or more of the other senses. For example, someone with synaesthesia may hear colour or see sound.

The Independent

I wonder how Mansfield experienced senses. Across Mansfield’s corpus of writing she blends and fuses the senses to create a dreamlike space for the reader, and to emulate the trance experienced by a character.

CONNECTION TO MANSFIELD’S OWN LIFE

Mansfield learned French at school, though surprisingly for a world class short story writer, maths was her strongest subject. Students who are good at maths also tend to be very good at languages — both maths and second-language learning rely on an affinity for patterns.

In New Zealand, French has traditionally been the language you take if you’re in the academic stream. Less academically inclined girls were channeled into the secretarial route. This remained true at least until my mother’s generation of girls (the 1960s). If you were in the academic stream you could be a teacher. Otherwise you could be a secretary or a nurse. Girls were of course expected to marry men and become mothers, which turned them into women.

Mansfield’s high school experience preceded my mother’s by half a century and I can’t imagine how stifled she felt as a natural-born contrarian. She did come from a well-off family, and probably knew even at high school that she’d be looked after financially, at least in the basic sense. Her father provided her with 100 pounds per annum. This covered her absolute necessities, though didn’t forestall money worries in Europe.

Mansfield could never be persuaded to study what she didn’t want to study, but she must have enjoyed her French classes. She learned French to quite a high level. Kathleen and her sisters would speak French to each other in front of adult acquaintances and were no doubt insufferable, because they assumed no one else around them was smart enough or worldly enough to understand what they were saying.

STORY STRUCTURE OF “CARNATION”

SHORTCOMING

This is the Shortcoming of any teenager almost anywhere — enforced boredom and constriction.

THE WINDOW

The two square windows of the French Room were open at the bottom and the dark blinds drawn half way down. Although no air came in, the blind cord swung out and back and the blind lifted. But really there was not a breath from the dazzle outside.

In Mansfield’s short stories, a constantly shifting perspective gives the reader a series of shocks, as one perspective shifts to another. In these stories, look for windows and mirrors. In “Carnation” the symbol happens to be a window.

Katie is experiencing nascent sexuality. Katie seems less mature than Eve — I gather this from Eve’s name but also from Eve’s relationship to sensory enjoyment. Until Katie looks out that window, it’s almost as if she’s never allowed herself to enjoy looking at a man like that. Yet she’s not fully mature. There’s still a glass pane between herself and that other, adult world.

But it’s not just the man Katie enjoys. This isn’t an eros that focuses on the man — he is incidental to her pleasure. Mansfield only describes the man’s body after describing all sorts of things in the environment, including the drops glancing off the wheel, the sound of the pump and so on. All of these things are quasi-erotic to Katie.

THE HATS

“Roses are delicious, my dear Katie,” she would say, standing in the dim cloak room, with a strange decoration of flowery hats on the hat pegs behind her…

Hats in Mansfield’s stories are repeatedly associated with systems of authority. (This is not stated but unarticulated) e.g. “The Tiredness of Rosabel“. In “Something Childish But Very Natural“, Henry’s story begins with him becoming separated from his hat in a different train carriage. This seems to relieve him of inhibitions. In “The Garden Party” the images of hats are incorporated in the action of the story not only because people wore hats in those days and put a lot of thought into them, but also because they are related to moral values.

What is the hat imagery doing here? Eve is ’embodying’ the flower, with all is overlapping sensory offerings. By putting on a hat covered in flowers she is ’embodying’ the sensory experience of flowers, perhaps. A floral hat is the inverse of stuffy, prim bowler hats and so on.

THE BIRD

When Mansfield compares people to animals, beasts, insects, water-creatures or birds, unpleasant emotions are revealed. Insects are helpless, snakes are cunning, spiders are hunting for prey. Rabbits are escaping. They all represent a cruel or suffering aspect of humankind.

Mansfield especially likes bird images. Bird comparisons comprise almost half of all the animal imagery. In some stories, birds represent freedom or happiness (because they fly and seem to sing joyfully).

The bird imagery in “Carnation” is an excellent example of how Mansfield makes use of birds. Katie’s laugh is compared to a bird, which Mansfield describes as scary:

And away her little thin laugh flew, fluttering among those huge, strange flower heads on the wall behind her. (But how cruel her little thin laugh was! It had a long sharp beak and claws and two bead eyes, thought fanciful Katie.)

Over the course of “Carnations” the character of Eve changes in Katie’s eyes, from a scary bird girl (more like a harpy) to a seductive bird girl (more like a siren).

colour SYMBOLISM

Mansfield uses colour for more than simply describing something. Colour images fall into two basic categories:

- Colour images related to the visual experience of the character looking at it

- Colour images expressing the atmospheric mood or a character’s mental state.

[Eve] brought a carnation to the French class, a deep, deep red one, that looked as though it had been dipped in wine and left in the dark to dry. She held it on the desk before her, half shut her eyes and smiled.

The carnation is literally deep red, but what of Katie’s reaction to it? She feels it has been ‘dipped in wine’ — an adult drink — ‘and left in the dark’ — where adult/secret acts happen.

Mansfield doesn’t use the colour red very often. Instead she uses purple, green and gentle colours such as mild yellows, greys and blues. She’s more inclined to focus on variations in light.

The colour in this paragraph is more typical:

Even the girls, in the dusky room, in their pale blouses, with stiff butterfly-bow hair ribbons perched on their hair, seemed to give off a warm, weak light, and M. Hugo’s white waistcoat gleamed like the belly of a shark.

So what of the red of the carnation in this story? There is clearly some burning passion going on, even if it’s without a specific target.

DESIRE

The girls don’t want to study French. They want to kick back on this stifling hot day.

At first Eve seems to be going for some strange social capital. That’s obviously how Katie sees her, and we’re encouraged to see her through Katie’s eyes. The weird girl who eats flowers:

On those hot days Eve — curious Eve — always carried a flower. She snuffed it and snuffed it, twirled it in her fingers, laid it against her cheek, held it to her lips, tickled Katie’s neck with it, and ended, finally, by pulling it to pieces and eating it, petal by petal.

I remember the first time I saw someone eating petals. It was on the 1987 movie The Last Emperor, Bernardo Bertolucci’s Chinese epic. After the royals are evicted from the Forbidden City the empress is sidelined. The Empress becomes so disaffected the filmmakers depicted her eating the floral displays at her husband’s coronation as emperor of Manchukuo, before moving on to the more diverting pastimes of opium.

We know she did become addicted to opium.

Don’t try eating poppies at home. Don’t try selling poppy seeds from a Wellington dairy, either, unless you sell a commensurate amount of other baking materials.

But carnations are actually edible, if grown organically.

When Eve eats the carnation, what’s that all about? This is part of Eve’s desire to eke every sensory pleasure from her environment. I believe she takes equal pleasure from seeing others do the same.

OPPONENT

The girls are divided in a binary way which feels reminiscent of an adolescent classroom, in which everyone experiences puberty in their own time.

Some of the girls were very red in the face and some were white.

Eventually the other characters are ‘killed off’, leaving innocent Katie counterposed to knowing Eve:

…most of the girls fell forward, over the desks, their heads on their arms, dead at the first shot. Only Eve and Katie sat upright and still.

Mansfield liked the technique of counterposing one character with another. In the same way, excited and searching Bertha is counterposed to the calm and contained Pearl Fulton in “Bliss“. Sabina is counterposed next to the pregnant woman in “At Lehmann’s“. In the “Prelude” trilogy Kezia is set next to Linda, Beryl and Mrs Fairfield. This method of juxtaposing characters’ attitudes and moods give structural unity to stories.

I see Katie and Eve as quasi-romantic opponents. Eve is the more stereotypical masculine figure, showing a sexually inexperienced feminine figure the pleasures of life. Katie is initially resistant, even to something as benign as a flower:

Oh, the scent! It floated across to Katie. It was too much. Katie turned away to the dazzling light outside the window.

The other Oppositional web is that which exists between the French teacher and his students, especially Francie Owen, who is decorating herself with ink. (I suspect if Mansfield lived today she’d be thoroughly inked in sleeves of floral tattoos.)

In Mansfield’s stories characters are often defying societal expectations in some way. Their French teacher is not a manly man, shown with the detail of the floral detail on his small, highly decorative book. The girls mock him, possibly because he defies their expectation of manliness:

How well they knew the little blue book with red edges that he tugged out of his coat tail pocket! It had a green silk marker embroidered in forget-me-nots. They often giggled at it when he handed the book round. Poor old Hugo–Wugo!

PLAN

The French teacher first wants the students to learn French, but there is resistance due to the heat of the day. M. Hugo acquiesces, and changes his lesson plan; now they will listen to him read French poetry.

The reactions to this news are various.

“Go—od God!” moaned Francie Owen.

So the ‘Plan’ in this story is driven by the teacher, but the teacher is soon released from his position as Oppositional character.

BIG STRUGGLE

The students listen to their French teacher read poetry. The narrative ‘camera’ zooms in on Katie, who looks out the classroom window and, with all of her senses fusing, she ‘experiences’ the body of the man pumping water outside, looking at him with The Female Gaze. Her experience of looking at him is close to orgasmic.

Now she could hear a man clatter over the cobbles and the jing-jang of the pails he carried. And now Hoo-hor-her! Hoo-hor-her! as he worked the pump, and a great gush of water followed. Now he was flinging the water over something, over the wheels of a carriage, perhaps. And she saw the wheel, propped up, clear of the ground, spinning round, flashing scarlet and black, with great drops glancing off it. And all the while he worked the man kept up a high bold whistling, that skimmed over the noise of the water as a bird skims over the sea. He went away — he came back again leading a cluttering horse.

She saw him simply — in a faded shirt, his sleeves rolled up, his chest bare, all splashed with water — and as he whistled, loud and free, and as he moved, swooping and bending…

The whole room broke into pieces.

This is the ‘Battle’ scene, and an excellent example of how Battle scenes don’t always look like big struggles/fights/skirmishes/arguments.

ANAGNORISIS

If we go outside the imagery of this particular story, In ancient Greek tradition, for instance, the carnation represented symbols of love.

What’s happening when Eve gives the flower to Katie? Eve is clearly an intertextual name, associated with temptation. Eve might be giving Katie an apple, in a gender-mix up of the Garden of Eden section of the Bible.

It seems to me that while Katie has been watching the man outside, Eve has been watching Katie. When Eve gives Katie the flower, it feels like permission to enjoy the experience of watching a man in that way. Eve is giving Katie the gift of the flower, but also the gift of permission — to enjoy any sensory experience that comes her way.

Is it sexual? It’s proto-sexual — enjoying sensory pleasures such as the feel of petals and water running across our feet is the first step to enjoying sexual pleasures.

NEW SITUATION

Mansfield’s stories tend to follow a regular pattern with the ‘positive’ theme dominant until the climax (the Battle). Then it comes into decisive conflict and is superseded by the negative theme. In other words, the story often takes a turn for the depressing at this point.

However, “Carnation” does not end like this. I see “Carnation” as a story about the blossoming and cementing of female friendship. When Eve gives Katie the carnation, they are experiencing an “I Understand You Moment”, a necessary component of every love story. (Without this moment the audience won’t believe that two lovers would be any good together.)

And “Keep it, dearest,” said Eve. “Souvenir tendre, [tender memories]” and she popped the carnation down the front of Katie’s blouse.

Keep what? Is Katie’s little epiphany permanent? I think so.

Though Katie may not understand why Eve gave her the carnation, she’ll always remember the moment. She may look at this particular carnation more carefully. She may enjoy its spicy scent and feel its velvety petals, all by way of learning to enjoy sensations, or perhaps by way of holding onto a childlike joy of sensory experience against the stifling environment of the teenage schoolroom.

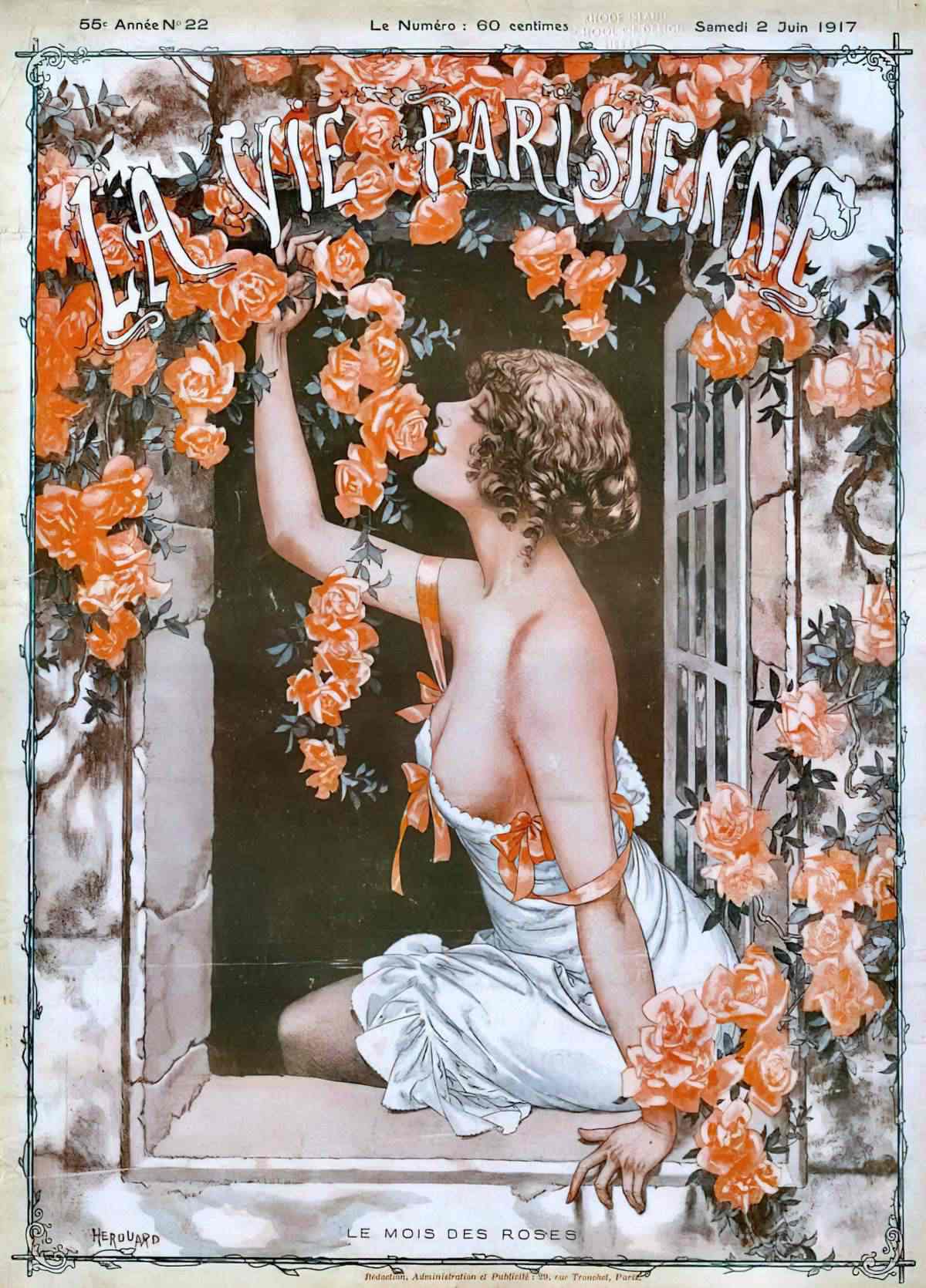

Header painting: Detail from La Confidence, by American painter Elizabeth Jane Gardner (1880).