Many writers say this: Stories emerge from the imagination when two different ideas come together in a new way. So it is in the title of this story. What do cafeterias and pools have in common? Evenings and rain? Moving into a new house?

“The Cafeteria In The Evening And A Pool In The Rain” is a short story by Japanese author Yoko Ogawa, published in the September 6, 2004 edition of The New Yorker. The story was translated from Japanese to English by Stephen Snyder. More recently, Deborah Treisman and Madeline Thien discussed this story at The New Yorker Fiction Podcast. (Analysis of the story begins at the 46 minute mark.)

A WRITE-IT-YOURSELF STORY

This is one of those short stories which requires readers to write part of it for ourselves. The author leaves gaps. We make our own connections.

“The Cafeteria In The Evening And A Pool In The Rain” is a bit of a weird one. The woman feels like the ‘main’ character but we never learn much about her. She meets a random man and his young son and we hear bizarre details about this guy instead of details about her. Why? How does this connect to the woman’s so-called anguish? Is she actually anguished or is she enjoying a quiet three weeks setting up a new house before her fiancé gets there?

What does all the water and reflection imagery mean?

I believe this Japanese short story is an excellent example of yugen. If you’re unfamiliar with that aesthetic, pop on over to this post, have a read. I’ll meet you back here. (tl;dr: Yugen is a positive characterisation of nothingness.) SO THIS STORY IS ABOUT NOTHING. No, not quite. The in-between bits aren’t nothing. They’re something.

Some readers will be emotionally affected by Ogawa’s “The Cafeteria In The Evening And A Pool In The Rain”. Madeline Thien was. She says the story hits differently each time she reads it. I don’t get that effect. My read is more analytical than intuitive.

WHAT HAPPENS IN “THE CAFETERIA IN THE EVENING AND A POOL IN THE RAIN”

ALONE IN A HOUSE IN THE COUNTRY

It is foggy. (How very yugen. Yugen is about obscurity but not total darkness.)

A woman in her early twenties arrives at a deserted new house in a semi-rural area of Japan where she is to wait for three weeks alone with her dog, Juju, before getting married. She’s not a huge fan of the house but the fiancé liked the place because it’s old and sturdy. She arrives to us in statu nascendi (without backstory). We learn more about the men in this story than about the unnamed narrator, who is functioning as more of a viewpoint character. Except a revelation at the end indicates she’s experience some kind of epiphany, which would make her a ‘main character’ by the usual definition. (This story doesn’t exactly pass the Bechdel test.)

But this effacement of the viewpoint character would be completely in line with the yugen aesthetic, because a yugen appreciation of nature demands no interaction between human observer and their environment. When describing a natural environment with yugen aesthetic, there are certain common tricks to avoid. Personification, anthropomorphism, chremamorphism… any way-of-seeing which turns the natural environment into something changed by having been seen by a human would be against yugen aesthetic. To approach something with a yugen mindset is to appreciate it without giving your opinion on it. Once you’re passing a judgement, you’re no longer humbled by magnificence.

ABOUT TO GET MARRIED

People in her life aren’t enthusiastic about her upcoming marriage. The fiancé isn’t much of a catch. He’s already been married and divorced. He’s been trying to pass the bar exam for ten years, plus he’s quite a bit older than she is. He has health problems. But the narrator will marry him anyway. Their relationship isn’t the meat of the story at all. Nor is the wedding day. This story isn’t even about her…

UNEXPECTED GUESTS

It starts to rain. She potters around the house, fixing things up. She’s is painting the bathroom when she gets unexpected visitors: a mysterious man and his three-year-old boy. The man is in his thirties.

The description sounds like something out of j-horror:

When I opened the door, I found a boy, perhaps three years old, and a man in his thirties, who appeared to be the boy’s father. They wore identical clear-plastic raincoats with the hoods pulled up over their heads. The coats were dripping wet, and rain fell from them onto the floor.

“The Cafeteria In The Evening And A Pool In The Rain”

So far, so ghost story. (It’s not a ghost story. But you could read the man and his boy as figments of the narrator’s imagination. If you wanted.)

I had the impression that they might vanish if I stared at them for too long.

“The Cafeteria In The Evening And A Pool In The Rain”

The raincoats are a creepy touch, especially since they’re not also carrying umbrellas.

Raincoats are getting to be a common item in the horror genre, to the point where you can almost expect a work to be a horror, or horror elements to suddenly enter a work, by the sight of a significant character wearing a raincoat.

Raincoat of Horror at TV Tropes

(Have you seen Dark Water? If Ogawa’s short story has put you in the mood for a super creepy Japanese horror film with rain and raincoats and old buildings and moving house, check that one out.)

By the way, it is normal and expected that Japanese people introduce themselves to new neighbours, not the other way around. Ideally you take a small gift with you. The introduction is pretty scripted: Your name, where you came from, pleased to meet you. Off you go. When I was an exchange student in Yokohama, my host mother took me around a surprisingly large field of neighbours and introduced me to all of the housewives. The narrator of this story should probably have done this? But she didn’t, probably because she’s a young person. This suggests she has moved here from a city. (In all countries I’ve lived in, there’s a significant cultural difference between city and rural areas.) Anyway, now she’s creeped out at the inversion of friendly neighbours introducing themselves to her.

The narrator gets the feeling the man and his kid belong to some kind of cult. She aims for evasive replies, not wanting to get sucked into anything weird.

THEY MEET AGAIN, AT THE LOCAL PRIMARY SCHOOL THIS TIME

She takes Juju for a walk. They’re making their way through a labyrinth of narrow streets when Juju takes off, heading straight for a three-storey school building. Darn it, he runs inside.

Well, this is weird. The man and his little kid happen to be standing by a cafeteria window at the back gate. Without their raincoats this time, they’re really well dressed. The guy apologises for bothering her the other day. He must realise he creeped her out?

And, ah, what are they doing hanging around the local school? The guy tells her his little boy loves the cafeteria so they come to see it in action. He points out it’s really amazing, preparing that much food for 1000 kids. Everything runs like clockwork to make that happen. I get the strong feeling this guy is autistic. He’s strongly affected by sensory input, he comes across a little creepy because he’s not following expected social scripts, and he’s attracted to things that work like clockwork. (I don’t believe he’s here for the son’s benefit.)

Of course, autism decoding my contemporary Western take. Yugen itself appeals to an autistic way of seeing the world, because yugen refers to an appreciation of patterns. Traditionally, this appreciation involves naturally occurring patterns, but the cafeteria is a man-made take on that. Perhaps that explains why it feels so overwhelming. (There’s nothing magical of fantastic about the yugen experience. An appreciation of the yugen aesthetic means appreciation of physical elements, grounded firmly in reality. You can’t get much more real than a school cafeteria, right?)

This guy smells like the sea. He’s wearing a beautiful green suit. He has long, slim fingers. He reads like a character out of a fantasy story.

The narrator tries to elicit from the man if he belongs to some religious organisation. She asks if he visits different neighbourhoods. This time, it’s the man’s turn to be evasive. They say goodbye.

SWAPPING TELEGRAMS WITH THE HUSBAND-TO-BE

The fiancé visits one weekend, does some jobs around the new hours.

The narrator and her fiancé can’t afford a phone so after he leaves they send each other telegrams instead. For Western readers, this harks back to a much earlier time but telegrams in Japan are still going strong. This article is from 2014, when telegrams could be sent by phone or Internet. In 2022, telegrams are still used in certain situations, especially by older generations. SMS hasn’t yet killed the Japanese telegram. In Japan especially, the medium is the message, and telegrams indicate more sincerity, more weight.

In any case, with a three hour delay between messages, the narrator and her absent fiancé swap occasional short messages e.g. about the wedding rehearsal, “good night”.

THEY MEET AGAIN, ON THE EMBANKMENT

I made a habit of walking along the embankment above the school whenever I took Juju out. But I didn’t see anyone at the gate again. Nor could I see into the cafeteria window from the top of the bank, no matter how much I looked. It seemed to be covered with something opaque, though I could never tell whether it was steam or spray or what.

“The Cafeteria In The Evening And A Pool In The Rain”

(Did the school realise a creepy guy and his son were peering into the cafeteria and put up some kind of film?)

Although the narrator doesn’t see the man at the cafeteria again, what do you know, she meets him on her evening walk. The little boy recognises the dog. I might be starting to wonder if I had a stalker myself, but not the woman in this story. Anyway, her dog likes him, and in stories if your dog likes someone that means they’re a goodie.

This time, she and the man get into an in-depth discussion about sensory processing issues. There’s a heavy emphasis on detail and overlapping sensory sensations in this story, to the point of synaesthesia. For both of them. This is their commonality. (Or possible evidence that the narrator has imagined him up.)

It is what photographers call ‘golden hour’. Until now the landscape has been mostly grey. Now ‘the clouds had become striated with pink, tinting the sky a deep rose color’ (The colour of shrimp, incidentally.)

The guy’s a close talker!

I could feel his breath, his pulse, the heat from his body.

“The Cafeteria In The Evening And A Pool In The Rain”

Unlike other parts of Asia, Japanese people have a large personal space. (To allow room for deep bowing, apparently.) It is VERY WEIRD that the guy is standing so up-close-and-personal.

Now we learn the reason for the short story’s title: Cafeterias in the evening and pools in the rain are linked for the man. Both sensations overwhelm. He can’t think of the right word to describe the emotion he feels around both, but it’s not pleasant.

The guy says,

I think you have to go through some sort of rite of passage, at least once in your life, that allows you to become part of the group.

“The Cafeteria In The Evening And A Pool In The Rain”

How might that relate to the narrator’s life? Well, she’s about to get married. In a strongly cisheteronormative culture, it is expected she marry someone. It is better she marry someone than no one, even if the marriage partner is less than ideal.

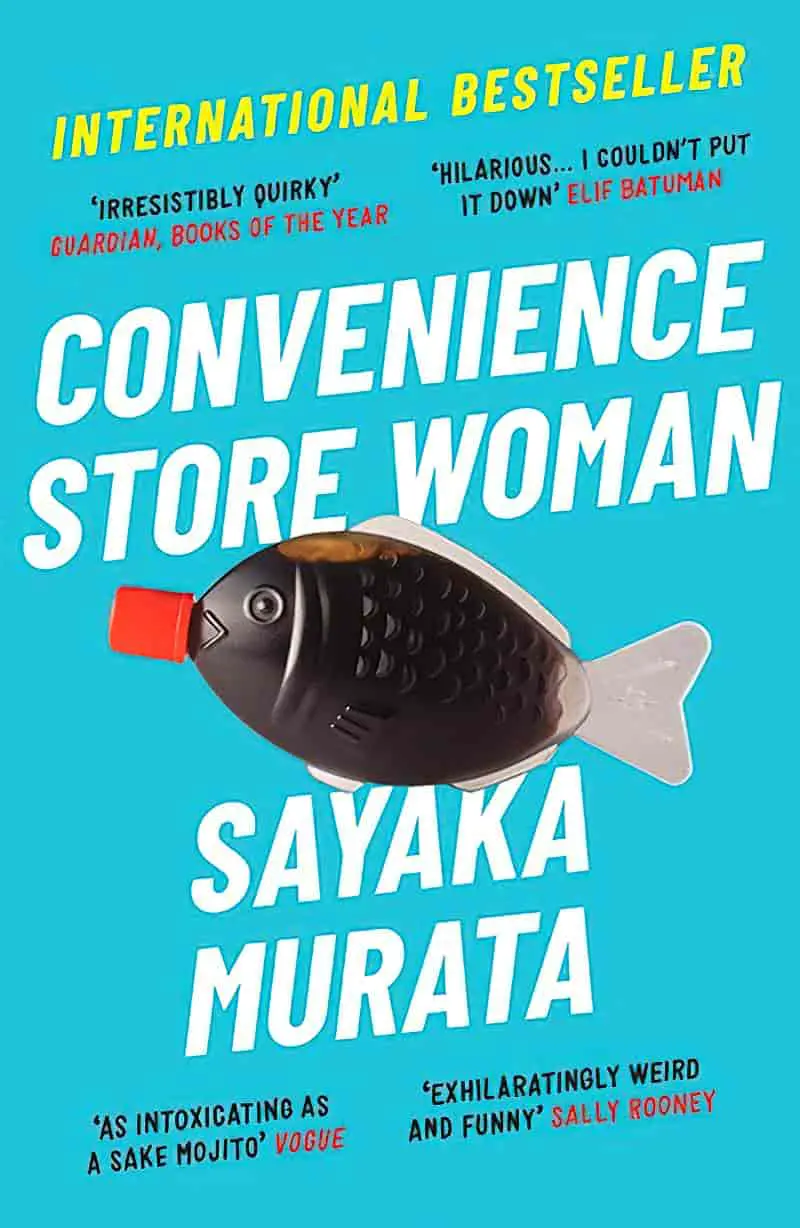

You know who has delved deep into that since this story was written? Sayaka Murata in her 2016 novel Convenience Store Woman. (English language marketing copy calls it “heart-warming”. I, uh, didn’t have that experience.)

Convenience Store Woman is the heart-warming and surprising story of thirty-six-year-old Tokyo resident Keiko Furukura. Keiko has never fit in, neither in her family, nor in school, but when at the age of eighteen she begins working at the Hiiromachi branch of “Smile Mart,” she finds peace and purpose in her life. In the store, unlike anywhere else, she understands the rules of social interaction ― many are laid out line by line in the store’s manual ― and she does her best to copy the dress, mannerisms, and speech of her colleagues, playing the part of a “normal” person excellently, more or less. Managers come and go, but Keiko stays at the store for eighteen years. It’s almost hard to tell where the store ends and she begins. Keiko is very happy, but the people close to her, from her family to her co-workers, increasingly pressure her to find a husband, and to start a proper career, prompting her to take desperate action…

A brilliant depiction of an unusual psyche and a world hidden from view, Convenience Store Woman is an ironic and sharp-eyed look at contemporary work culture and the pressures to conform, as well as a charming and completely fresh portrait of an unforgettable heroine.

Now the guy in the green suit tells an unlikely story about his own childhood cafeteria experience. As a kid, the fat women in the school cafeteria prepared food in a way which led to him being unable to eat. (He seems to be describing an eating disorder. Or fatphobia. Both.)

It was awful; and, after that, cafeterias had the same effect on me as pools did. I knew that no matter how hard I flailed I was still going to sink to the bottom, just as I knew that every time I tried to take a bit of cafeteria food the fat ladies with their shovels and boots would be there to make sure that I choked.

“The Cafeteria In The Evening And A Pool In The Rain”

A MEMORY INVOLVING GRANDPA AND A CHOCOLATE FACTORY

Now the man recalls another childhood memory. He bunks off school and just so happens to run into her own grandfather, a drunkard who is wandering about with an almost empty beer can.

The grandfather takes her to a secret place, which happens to be an abandoned chocolate factory. We get the red motif again, with red grit on the floors. The place feels kind of steampunk.

This grandfather describes huge chocolate bars, the size of two tatami mats. Incredulous — as you would be — the grandfather encourages his grand-daughter to smell the equipment for herself, as proof the machinery used to make chocolate bars. I get a Willy Wonka vibe. Japanese edition.

As this guy wraps up his epic story (within a story), darkness falls and now his face is cast in shadow. Yugen! Shadows! Meaning in the shadows!

I wanted to tell him something, so much that it felt like a weight on my chest. If I didn’t, it seemed that his face might actually disappear.

“The Cafeteria In The Evening And A Pool In The Rain”

The tête-à-tête ends. Man and boy leave our narrator alone, but after hearing this childhood anecdote from a random dude at sunset, something inside her has changed. She recalls the telegram from her fiancé, wishing her a simple goodnight. She wants to hold the paper in her hand. She wants to grasp something, even if the meaning of this encounter has meaning which doesn’t yet offer itself up. She won’t be seeing this pair again because they’re off to find a different cafeteria to admire. Through the window, this one disappears as if into a boggy marsh.

She starts running in the opposite direction.

ANALYSIS OF “THE CAFETERIA IN THE EVENING AND A POOL IN THE RAIN”

WAVES

The fog was rolling away in gentle waves.

“The Cafeteria In The Evening And A Pool In The Rain”

Waves are important to an understanding of yugen. In Buddhism, everything eventually dissolves into nothingness. Nothing is ever finished or perfect — everything in the universe is in a state of flux. As soon as something reaches its peak it’s on its way back down again in an endless cycle. (Although this is an ancient concept, it lines up nicely with what contemporary astrophysicists believe about how big bangs keep happening, universes keep forming and then they keep dying — over and over into eternity.)

If you’ve visited temples in Kyoto, or seen photos, you’ll be familiar with the wave patterns in the stones of the traditional Japanese dry gardens.

MACRO AND MICRO: UNIFICATION, EVERYTHING IS CONNECTED

The author of this story, Yoko Ogawa, is generally known for writing about mathematics and equations, as if trying via story to figure out the intricate workings of the universe.

The details in this story combine the macro with the granular:

I stared at [the fog] for a long time, leaning against the boxes, until I felt as if I could see each milky droplet. […] A bird flew straight into the fog and disappeared.

“The Cafeteria In The Evening And A Pool In The Rain”

LONELINESS VS SOLITUDE (OR IS IT JUST YUGEN?)

I wasn’t a bit lonely, despite being alone.

“The Cafeteria In The Evening And A Pool In The Rain”

Madeline Thien feels the short story is all about relationality: “You will always be there, and I will always be here,” everything and everyone in their place, but also an inability to change things from their (rightful) place. “There will always be this thing floating between us.”

The ‘thing’ floating between us is a pretty good description of yugen. The shadows between are important.

A question not answered by the text: Why isn’t the fiancé helping her move in? Although she is alone, the narrator tells us she is not lonely. Madeline Thien feels there’s “something inevitable” about why the narrator came to this house to set it up alone. We get no sense that something bad has happened between herself and the absent fiancé.

This all feels refreshing to me. Read enough Western stories and you start to pick tropes. Stories aren’t inevitable so much as predictable. When I get to feeling like that, a work in translation is usually the answer, especially if the story is from Japan, with a different history of tropes, mythology and symbolism. I feel if this were an American story, say, we’d get more about the relationship between the narrator and her absent fiancé. His absence would be explained. We’d be given a flashback about a time they were having sex together, and this would mean something about the health of the relationship more generally. It’s refreshing to get none of that. It’s refreshing that she meets another man and there’s still none of that.

THE WOMAN-DOG LOVE STORY

“The Cafeteria In The Evening And A Pool In The Rain” is also a love story for dog owners. Rather than the dog standing in as second-rate proxy for the absent fiancé, Juju is an important source of emotional support in his own right. The home must suit Juju as much as it suits the human inhabitants.

At the same time, he is very much a dog and the story includes comedic moments. He runs off into the school; he is startled when the narrator needs a cuddle from him.

As pointed out in the podcast, we see the dog’s desires and yearning. Dog and child quickly become close. This juxtaposes against the reserve between the man in the story and the narrator. I’ll add that it’s a strange kind of reserve. Is it really reserve, to introduce yourself to a new neighbour? To ask about someone’s ‘anguish’ right away? To stand extremely close? To launch into personal stories from your own childhood, including the bit about your alcoholic gramps? This isn’t your stereotypical Japanese reserve at all.

WATER IMAGERY

Notice the many images around water and transparency. As Madeline Thien says, “Everything’s roiled together in this joy that gets more and more intricate, but hard to name.”

The next day it rained. It was raining when I woke up, and it rained all day without a break. Fine, threadlike drops slide down the window one after another. The house across the way, the telephone poles, Juju’s kennel — everything was quietly soaking up water.

“The Cafeteria In The Evening And A Pool In The Rain”

“You can follow the trail through the cafeteria dish line to the pool,” Deborah Treisman adds.

What’s with the shrimps? In a Western story, the murder of the shrimps would foreshadow death. Ditto for the repetition of the colour red and pinks against a backdrop of undefined foggy, misty, rainy greys. Not here, though. No one dies.

ANGUISH

The man with the little boy thinks he can read anguish in the narrator. Personally, I find this annoying. Some rando turns up at my door and, without being asked, he’s telling how I feel? Like he knows me, or something. This is on a par with being told to smile, right? Under the assumption you’re insufficiently happy, like there’s a correct way to feel, and someone else can know you by looking at you.

I’m not surprised the narrator finds him a bit intrusive. It’s this, not the unexpected house call.

But now the reader will be wondering if this is a young woman in anguish. We want more information about the imminent wedding. She has been disconnected from her friends and family, since “everyone” disapproves of her choice of man. No one will be there at their wedding, aside from the two of them.

The anguish is borne of loneliness, right? I mean, that’s the easy reading.

THE ENDING

“The Cafeteria In The Evening And The Pool In The Rain” is a classic example of an ‘aesthetic closure‘, commonly seen in lyrical short stories. Feelings rather than action drives the drama in this story (which is apparently unlike the author’s other stories).

Perhaps this is the greatest love story of all: Two people who are happy alone but together. This woman loves her fiancé. At the end she craves to hold his telegram in her hand. She feels this longing even though he has low status in Japanese society, and would be considered un-marriageable due to having no salaried job and no savings.

I think this woman is fine. What she doesn’t have: Money. A husband with good prospects. Close friends.

What she does have: The ability to feel content with these gaps in her life. A good imagination?

The man and his boy move on. He’s like a travelling angel, a white hat cowboy in a Western, a Mary Poppins nanny, galloping/floating from town to town, telling the exact stories that people in anguish need to hear before they can appreciate what they’ve got.

Or something.