Burglar Bill is a picture book by Janet and Allan Ahlberg, first published in 1977. There are a number of picture books about burglars who break into houses at night, one of a child’s greatest fears going to sleep. Burglars can be found all across children’s literature. (Enid Blyton loved burglars.)

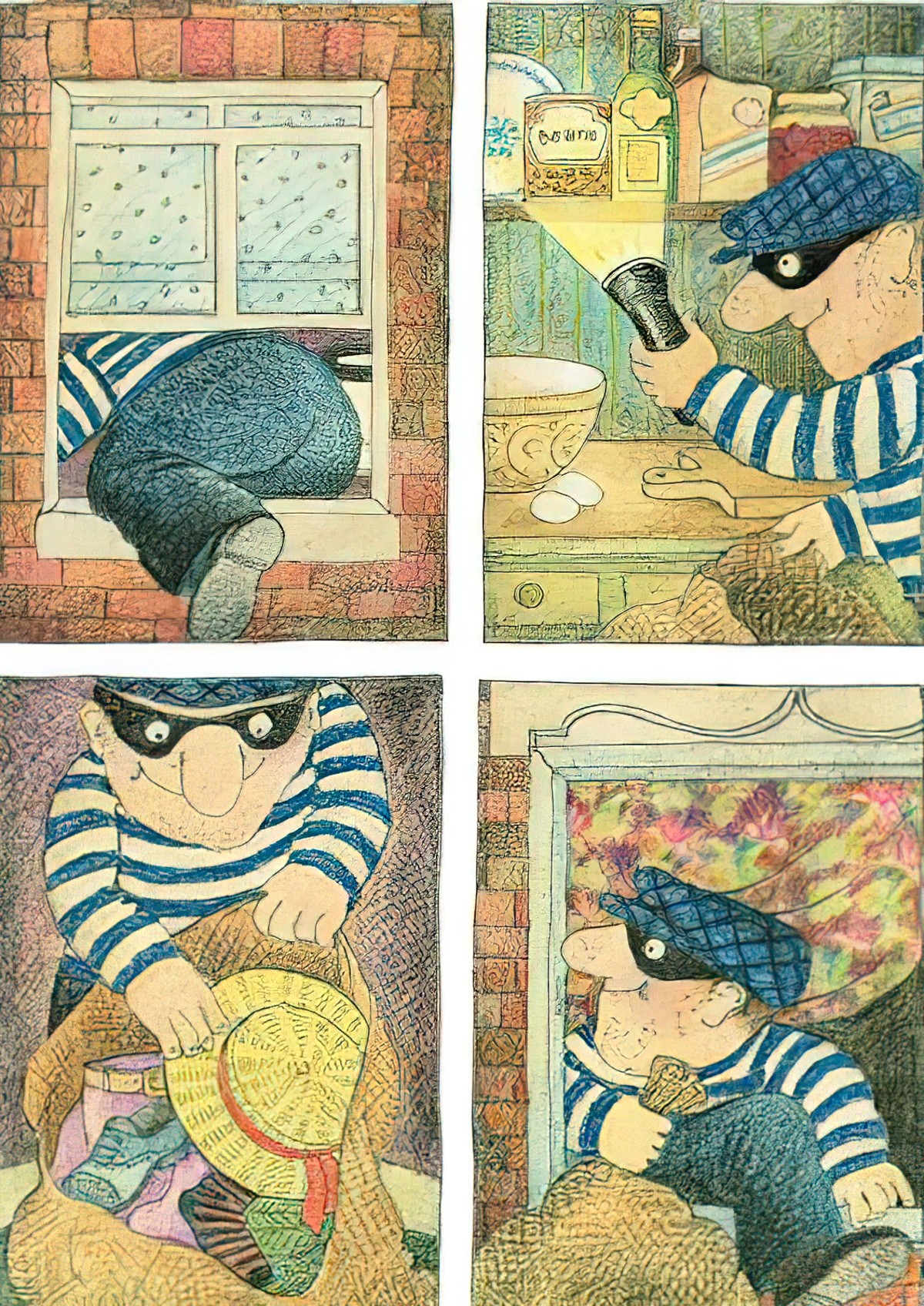

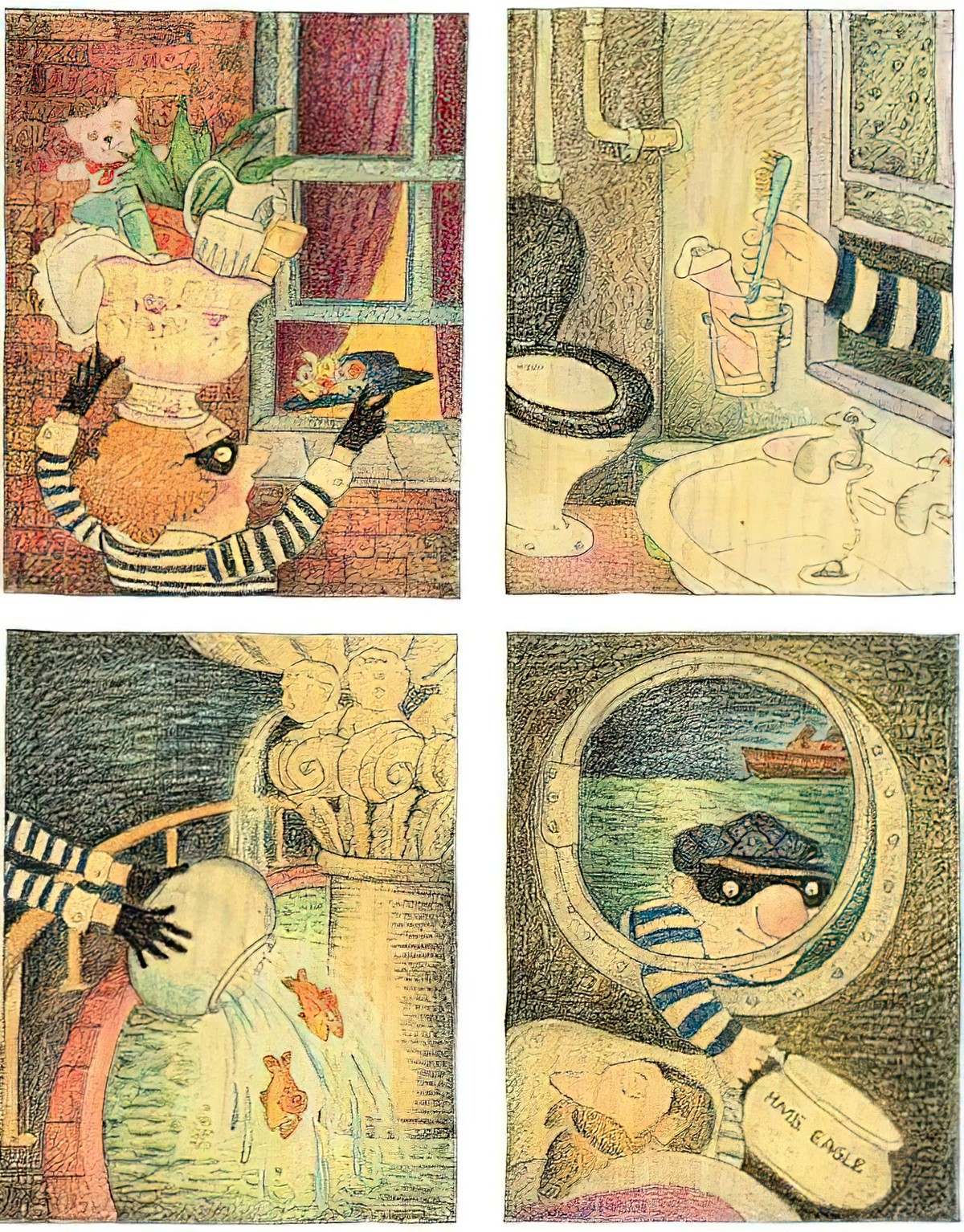

Be sure to examine the pictures in this one as there are plenty of visual gags. I love that Burglar Bill hangs a mugshot of himself on the wall.

I believe Burglar Bill has been hugely influential on the comical burglar stories that came after, notably:

Children’s comedy cartoons often include an intruder episode as well:

- “Family Business” (Courage The Cowardly Dog)

- “Homer The Vigilante” (The Simpsons)

- “Teeth For Two” (CatDog)

Children…expect the stories they hear to cast light on what they are unsure about: the dark, the unexpected, the repetitious and the ways adults behave. Quickly learned, their grasp of narrative conventions is extensive before they have school lessons. For children, stories are metaphors, especially in the realm of feelings, for which they have, as yet, no single words. A popular tale like Burglar Bill (1977) by Janet and Allan Ahlberg, invites young listeners to engage with both the events and their implicatiosn about good and bad behavious in ways almost impossible in any discourse other than that of narrative fiction.

Peter Hunt, International Companion Encyclopedia of Children’s Literature

THE IRONY OF BURGLAR BILL

Below, Francis Spuffords describes, among other things, how Burglar Bill appeals to adults as much as to children:

The journeys that picture books take a small child on are very often journeys around the familiar. Burglar Bill in Janet and Allan Ahlberg’s phenomenally successful picture book wears a stripy burglar’s jersey and the traditional eye mask. The child who meets him has been introduced to a useful stock figure, maybe their first outlaw, and the wicked energy he represents is getting an outing. But what Burglar Bill does, once he has inadvertently stolen a baby, is to change nappies and warm up bottles, returning to the most familiar rituals with the difference that he is carrying a swag bag. The Ahlbergs’ Baby Catalogue takes this to its logical conclusion. It offers the pure pleasure of recognition, and nothing but. Its pages are arrays of feeder bottles and potties, little cardigans and high chairs, alternative mummies and daddies (recognisable as nicely observed types in the human zoo, so that even this virtually wordless book is already giving the adult intermediary who offers it to a child a little something for him- or herself, as the best picture books do, pleasing the social intelligence of adults on the quiet.)

Frances Spufford, The Child That Books Built

Common writing advice given to storytellers: Only include a character’s backstory if it is unexpected (ironic). Otherwise, trust the audience to know basically how a character got to where they are when the story opens.

When it comes to ironic backstories, a pattern soon emerges:

- A now successful character was once destitute/an underdog

- A now criminal character was once square and law abiding

Burglar Bill is an example of narrative convention subversion, in which bad guys end up in prison, unredeemed. This kind of subversion works better on the adult audience, who has seen many stories pan out like this. A child audience doesn’t have have the story background to expect anything. So Burglar Bill is an example of a children’s story which works ironically for the adult portion of the dual audience.

SETTING OF BURGLAR BILL

In heteronormative England of the 1970s, when a happy ending for a man meant finding a woman. This is a picture book which exemplifies the saying, “Every Jack has his Jill”.

The grammar of the dialogue is that of the working class, though perhaps someone can pinpoint the area. I’m guessing somewhere in the Midlands, but only because that’s where Allan grew up, and where he set his memoir, which he called The Boyhood of Burglar Bill.

STORY STRUCTURE OF BURGLAR BILL

PARATEXT

Janet and Allan Ahlberg’s hilarious picture book, Burglar Bill.

Burglar Bill is an entertaining picture book by the iconic British husband and wife picture book team Janet and Allan Ahlberg, creators of Peepo! Perfect as a bedtime story and for children learning to read!

Who’s that creeping down the street? Who’s that climbing up the wall? Who’s that coming through the window? Who’s that? … It’s Burglar Bill.

MARKETING COPY

SHORTCOMING

Burglar Bill is a typical working bachelor but for one thing: He works on the wrong side of the law. The storytellers flip only this part of him, and echo the mirroring in the setting: Burglar Bill works overnight rather than during the day.

Many law-abiding and vital shift workers also work at night, but there is a long-established trope that bad things happen at night, and bad people operate under the cover of darkness.

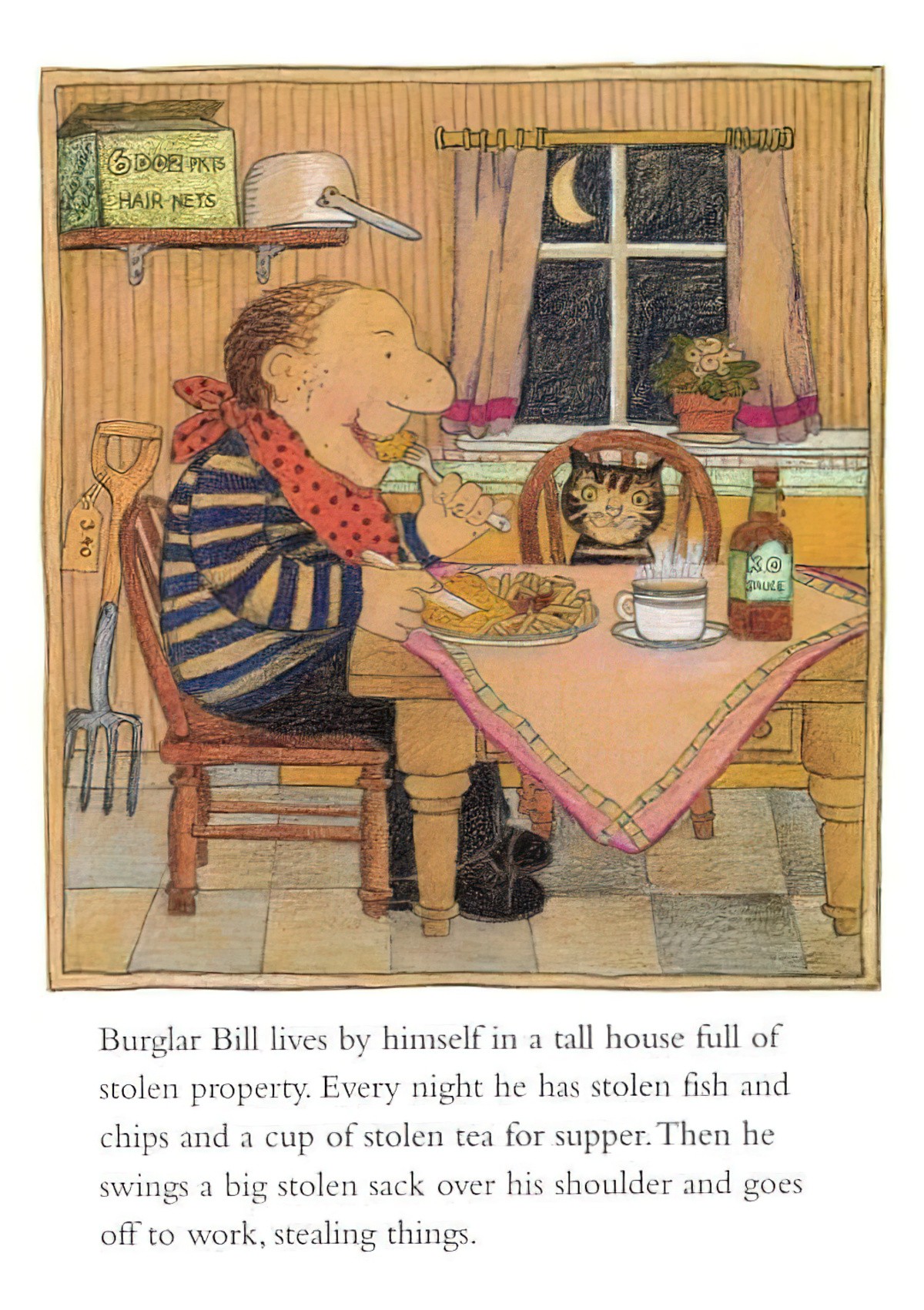

Bill’s psychological shortcoming is that he is lonely. On the opening page he is shown with a cat, but the cat eyes his dinner. In some picture books, such as in Pettson and Findus, a cat is a perfectly good life companion, but this cat (comically rendered in the same stripes as Burglar Bill’s shirt) is a second-class family member. “Burglar Bill lives by himself,” we are told at the very beginning. “But he’s not by himself,” I think, until realising later that for all intents and purposes, he is.

Burglar Bill’s loneliness will be fixed by the end of the story.

DESIRE

Some comical picture book burglars are commonly childlike characters who seem to be driven by kleptomania rather than by evil or greed. Burglar Bill is in the same category as Kate di Camillo’s burglar in Mercy Watson Fights Crime, in which the burglar is after the toaster. The toaster just so happens to be Mercy’s favourite appliance, as she has a penchant for hot, buttered toast.

OPPONENT

The owners of the houses remain unseen in this story, as do the police. But the storytellers do something interesting with police: rather than omit them entirely, they suggest nearby police. First with the proximity of the police station, next with the baby who wails like a police siren.

The interesting opposition in this story is Burglar Bill vs. The Baby.

Eventually Betty turns up to be the love opponent, though they pretty quickly hit it off. Betty doesn’t waste any time in asking Bill if he’s married.

PLAN

Bill makes a living by breaking into houses at night. He treats this like a day job and therefore steals many things successfully.

There’s nothing in the story about what he does with all these things. He steals what catches his fancy, without an eye to the second-hand retail market. We assume he fills his house with his stolen things and doesn’t need to earn cash. (The pictures of Bill’s home suggest a bit of stolen clutter.)

When Bill learns he’s accidentally stolen a baby he doesn’t think to find its parents. ‘Clearly’ this baby was left on a doorstep because whoever gave birth to it doesn’t want it. At this point I’m reminded of how easily children acquire pets in stories. This has changed in recent children’s fiction. In the 1970s, preceding microchipping, children in stories would often find a pet and just keep it. Authors don’t do that now. There’s almost always at least some effort expended in trying to find a pet’s owner.

THE BIG STRUGGLE

When the Baby talks, I’m reminded of “The Child” a short story by Ali Smith, in which a woman finds a baby in her shopping trolley, takes it home and soon realises the baby has a foul mouth on it.

Authors can’t get away with that kind of language (or baby) in a picture book but when the baby starts talking to Bill, readers are delighted. It is wonderful to find out the baby has agency.

Bill’s struggle to look after the Baby is ostensibly because he is a single man. A single man can’t possibly know how to wash the baby’s clothes, fasten a nappy, or how to strap Baby into a pram (he uses a wheelbarrow).

The “near death” calamity happens when Bill accidentally falls off his stool while trying to calm Baby down with a song on the piano.

The strugle sequence with the baby ends when Betty turns up to burgle Bill. This is a take on the classic con-man gets conned trope. It was later utilised in Dirty Rotten Scoundrels. In both cases, the woman goes undercover simply because people are inclined to trust women.

ANAGNORISIS

By coincidence, Betty is Baby’s mother. This is the sort of coincidence that only works in comedic picture books, but it also works because we can assume that in this cosy little world Bill and Betty are the only two burglars in town, and that fate has pulled them together.

Bill realises he and Betty could get married and he could be a step-dad. The ‘I Understand You’ moment happens for the reader when we see Betty steals the exact same things as Bill. They are identical except for their gender.

To set a good example for the baby, he and Betty will turn their lives around. So they return everything they’ve stolen.

NEW SITUATION

The final image shows us that Bill has given up burgling houses and is now a baker. Since bakers need to get up in the small hours, this is a good career change for Bill.

EXTRAPOLATED ENDING

I’m sure Bill and Betty were very happy together. Here’s Bill holding an umbrella for Betty while she deals with the baby. Once Bill learns how to parent, he’ll be an involved and kindly father.

RESONANCE

Burglar Bill was performed at a 2006 event in honour of the Queen’s 80th birthday, clear evidence that Burglar Bill is a British classic.

Stories about thieves are old as the hills:

THEFTS from Baughman’s Type and Motif Index of the Folktales of England and North America by Ernest Warren Baughman 1966.