Okay so “Disneyfication” is a thing. The word refers to how Disney typically takes a nightmarish, harrowing fairy tale and bowdlerises it according to the more conservative end of its perceived audience.

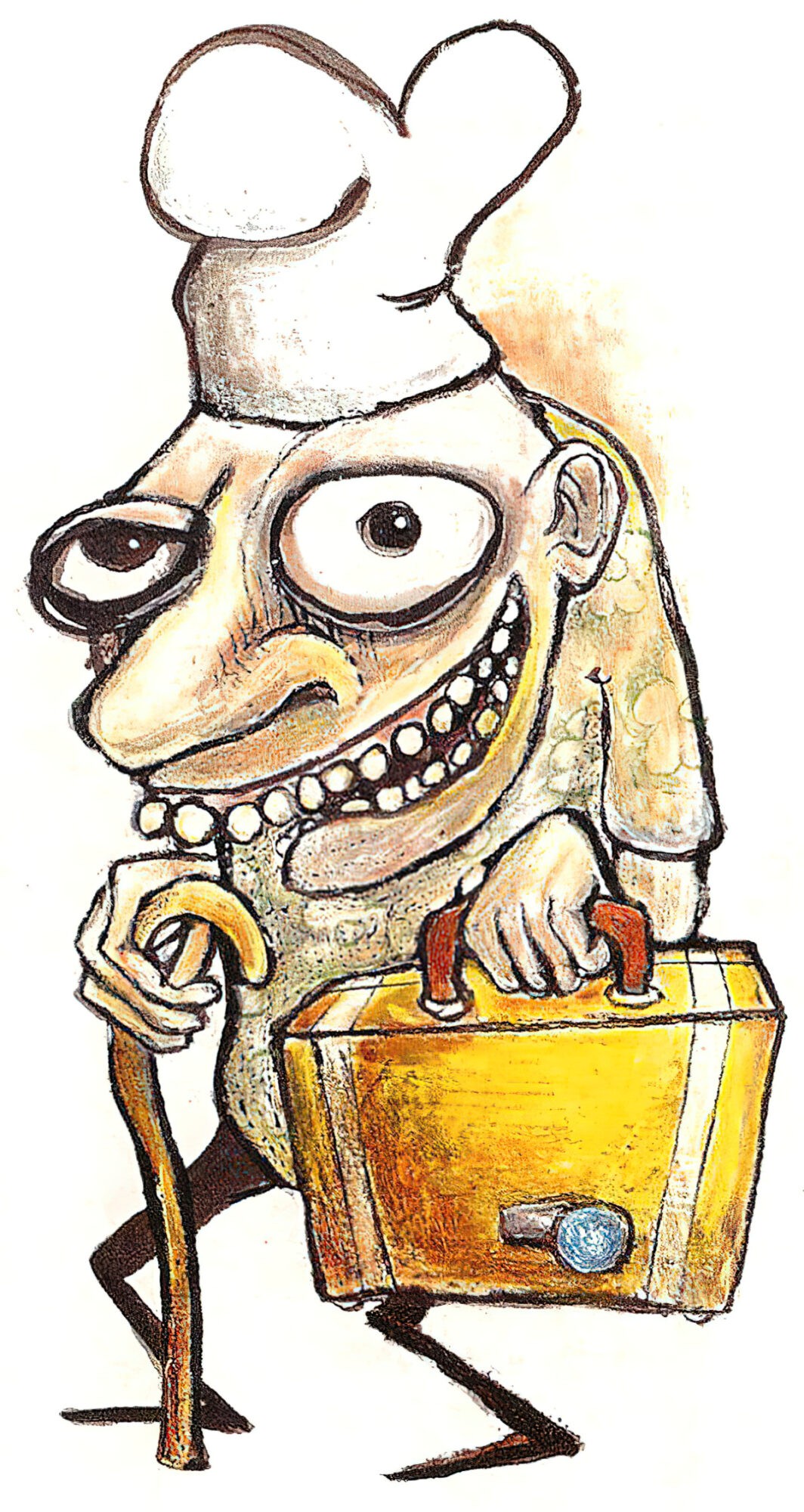

But lest we forget: In 1993 the Disney corporation also published a short story as disturbing as your typical pre-Grimm fairytales, replete with cannibalism. Disney had run a “Scary Tales” competition, and “Bunny Stew” was the winner. Disney commissioned Matthew Daly to create illustrations for the story.

Let’s Remember Miss Mikhaila “Mikki” Mares, and how her 1993 Disney Adventures Children’s Magazine Scary Stories Contest Winner is still more disturbing than anything Stephen King or Thomas Ligotti have ever done.

Combined.

Also, as Marxists, we should note that the entire tragedy hauntingly described was caused by Capitalism, which both destroyed the youth of the antagonist and structurally denied him the mental health care he desperately needs.

Misanthropes of the World Unite

“Bunny Stew” (728 words) is useful for use in a middle school/high school classroom because it was written by someone who had a great idea for a story, but not by someone with years of writing behind them. This short story is the kind of thing teachers hope to elicit from students. I’d use it as an introduction to a creative writing unit, not for deep literary analysis.

Students typically love to write scary stories. (If your school district lets you away with it, try getting them to write their own urban legend.)

Bunny Stew (Mentor Text)

Rachel combed back her auburn hair. Mom had told her to look nice for Grampa’s arrival.

The best opening paragraphs carry extra meaning upon second read. What does it mean to ‘look nice’? (On second read: ‘look delicious’.)

Then she sat in a recliner in the front room, thinking. Grampa had been living in Tampa Bay, Florida, until recently. Gramma had lived with him in a rest home until a year ago when she died of a stroke. Rachel remembered flying down for the funeral. Grampa had seemed OK.

Don’t get me wrong, this story works. It doesn’t work quite so well with too much thinking.

But recently the rest home had called, saying that Grampa had been acting strangely. They said he should live with his family for a while.

My refrigerator moment: Where has Grampa been living this past year? Later, the rest home people said he needs to live with family. But he can’t have been living with Rachel and her mother, because he knocking on the front door to come ‘home’, and Rachel is encouraged to ‘look nice’ for him.

Rachel couldn’t help feeling strange. She walked to the family room and picked up her bunny, Bud. She walked around, holding him. Just as she was about to get him a carrot, the doorbell rang five times. Rachel hurriedly put down Bud and ran to the door.

The writer makes use of repetition of ‘strange’. She senses something off, which her mother can’t seem to pick up on. In stories, animals and young people often have an extra sense, lost to the logical, analytical world of adults.

She wished she hadn’t hurried. When she opened the door, a little man stood there. He was leaning on a big cane and his dark, beady eyes seemed to penetrate her body. Then she recognized him.

The ‘little man’ is straight out of fairy tale. But why is Rachel’s grampa small? Metaphorically, he has diminished in her eyes as a grown man she can trust.

“G-Grampa?” she said quietly. “I-It’s me, Rachel.”

How much of this is dementia, and how much magical? This story could be read as an allegory for dementia, with grandparents doing very strange, and sometimes disturbing, things.

He reached out for Rachel’s hand. Rachel bit her lip and reached for a handshake. She let go a tiny squeal when she felt how strong the little man was.

When the mind goes before the body, strength can be a shock.

Rachel couldn’t eat her dinner. She kept noticing how Grampa was looking at Bud in his cage, watching his every move. Rachel was startled when he spoke, looking directly at her.

Rachel, and only Rachel, is worried about her grandfather, noticing what her mother does not.

“During the Depression,” he said quietly, “my wife and I used to raise bunnies. Big fat ones like that.” He pointed a finger at Bud. “Killed them all with our knife! Used ’em to make good bunny stew.” Rachel shuddered and left the room.

Rachel is of my own generation. Contemporary young readers won’t have grandparents who lived through the Depression.

“Why does Grampa act so weird?” Rachel asked.

This paragraph marks an adept change of time and place.

It was 8 at night and Rachel was in her mom’s room.

“Well,” her mom said, “he loved Gramma very much. When she died, I guess he missed her. Well, it affected his mind.”

The answer Rachel’s mother gives probably isn’t the real one. People search for cause and effect, and will settle upon ‘wrong’ cause and effect rather than settle with ‘don’t know’.

“Oh,” was all Rachel could say about that. “Well, tomorrow at school it’s going to be so much fun. My teacher, Mrs. Chrony, is bringing my costume tomorrow for the Easter play. I’m going to be the Easter bunny!”

At this point, the reader will guess what’s about to happen. This isn’t a problem. Pop wisdom says that readers love to be surprised, when really, readers love to feel smart. Readers love to be proven right. Also, there’s comfort in seeing something unfold when you know what that thing is.

The next morning, Rachel was making herself a sandwich for lunch when Grampa walked into the kitchen. She was using the big meat cleaver, the only clean knife left, to cut her sandwich. Grampa looked at the cleaver.

The author is good at mixing the everyday with the macabre. Macabre: A meat cleaver. Everyday and relatable: Using an inappropriate item because you can’t be bothered wiping a smaller knife.

“That’s the kind of knife we used on the bunnies,” he said. “Sharp knives like that one!”

Grampa is living in the past. He reminds me of a war veteran as much as someone who lived through the Depression.

Rachel quickly shoved the knife back into the drawer and left for school.

The adverb ‘quickly’ is technically unnecessary here because ‘quickness’ is embedded into the meaning of ‘shove’. That said, sometimes writers include extra words to achieve a pleasant rhythm.

Rachel was very happy walking home from school that day. Mrs Chrony had let her wear her Easter bunny costume home so she could show her mom. When Rachel opened the door to the house, a strange smell filled the air. She put down her book bag.

It’s a good idea to ground a story in a ritual. Here it is Easter. In Planes, Trains and Automobiles it is Thanksgiving.

“Er, Grampa, are you cooking?” she called.

“Yes,” came the reply, “good stew for us.”

This is masterful. “Good stew for us” is beautifully simple, and functions as the story’s memorable leitmotif. I’m reminded of a similar leitmotif in a strange children’s story about slugs, who eat the ‘juicy lettuces’.

Rachel walked slowly to the kitchen. Grampas’ back was turned to her. she saw a pot bubbling on the stove. She walked over to see what kind of stew it was. Staring up at her was Bud, his lifeless eyes still in his little head. Rachel gave a terrified scream.

The bubbling pot is another fairy tale prop, typically associated with witches, or femininity in general due to its rounded (pregant) shape. Bear in mind, not all witches convicted during the witch craze were women (though most were).

Grampa turned and looked at her. In his hand he held a bloody meat cleaver. Rachel screamed again. Grampa’s eyes widened.

Haha. Straight out of a B-grade horror movie. Eyes are important in horror. Think of Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Tell-Tale Heart“.

“It’s a bigger bunny!” he said, pointing at Rachel. “It’s a bigger bunny for stew!”

The payoff. The reader saw this coming, probably.

Rachel started backing away from the approaching man.

Brilliantly, the writer switches from ‘Grampa’ to ‘the man’. She no longer recognises him. He’s possessed.

“No, Grampa!” she cried, “I’m not a bunny! It’s me, Rachel!”

Since he’s no longer Grampa, the name Rachel means nothing to him.

The old man just kept muttering happily, “A bigger bunny for stew! Oh!”

Rachel could see she was getting closer to the wall.

‘Could see’ is unnecessary filtering and could be left out.

“Please, Grampa,” she kept saying, “it’s me! It’s Rachel!”

Rachel felt her back hit the wall. Grampa blocked all her escape routes. She gave one final cry as he raised the cleaver.

“Please, Grampa! No!”

The ‘camera’ cuts before the gruesome murder scene.

About 15 minutes later, Rachel’s mom got home. As she opened the front door, a strange smell filled the air.

“Whoa, Dad, are you cooking?” she called.

This reaction suggests Grampa has a history and was never to be trusted in the kitchen.

“Yes,” came the reply, “good stew for us.”

The final sentence of any story carries a lot of weight, so if you’ve set up a brilliant leitmotif, it’s a great place to end. Why is it brilliant? Because readers are likely to recall the phrase whenever they see stew bubbling.

Write Your Own Short Horror Story

Using “Bunny Stew” as your mentor text, create a scary story. To get you started, here are some questions, which you are free to use or discard:

- Think of a main character. It might be yourself. This story will be very short, so you won’t have time to flesh them out. So what are their basic characteristics? (Age, gender, pet, family, an identifying physical detail e.g. ‘auburn hair’)

- Is your story set in the real world or is there something odd about it? Are there places that tend to scare you? (e.g. the circus, the emptiness of a suburban mall just as shops are opening, a fairground, a new school, a playground at night.) If you’d like illustrations for inspiration, see here.

- Is this story set at a special time of year? Halloween is a popular choice for horror stories, but this writer subverted expectations by choosing Easter. It might be an event shared by a community rather than by an entire religion. It might even be a made-up event, only relevant to the world of the story. (See: “The Lottery” by Shirley Jackson or “Singing My Sister Down” by Margo Lanagan.)

- Who is the baddie/villain/opponent? It’s good to take a character who is normally kind and harmless and turn expectations upside down.

- Think of an object to associate with the villain. In “Bunny Stew” it is a meat cleaver.

- Think of a brief backstory for the villain. It doesn’t need to be much. In “Bunny Stew”, two reasons are given for the grandfather turning cannibalistic (and neither of them hew to realism): He lived through the Depression (historic) and he is dealing with grief (the recent event which tipped him over the edge).

- Think of fairy tales. If you read fairy tales as a kid, or ever saw something scary on TV, what was it that terrified you? Can you repurpose it in a different plot?

- This one’s a bit harder and may not come to you immediately: Try to include a leitmotif. The writer of “Bunny Stew” came up with “good stew for us”. It doesn’t need to be fancy. Is there something a family member says which you can repurpose for horror?

- Leaving gore off the page, what happens at the climax?

- After the climax, you have one paragraph to show the reader how things will be from now on. Which characters are still there? (Any?)