Aggressiveness is culturally induced: where it is not valued, it is not strong.

Marilyn French

“Middle school wasn’t much fun for me. We had some bullying going on, and the best thing to do was to stay out of their way.”

Jeff Kinney, author of Diary Of A Wimpy Kid

WHAT IS BULLYING?

Bullying is repeated verbal, physical, social or psychological aggressive behaviour by a person or group directed towards a less powerful person or group that is intended to cause harm, distress or fear.

If two people disagree, that is not bullying.

If two people dislike each other, that is not bullying.

A single episode of aggression also does not count as bullying. This is especially important because an act of retaliation on the part of the bullied does not mean ‘both sides are at fault’.

COMMON BULLYING TACTICS

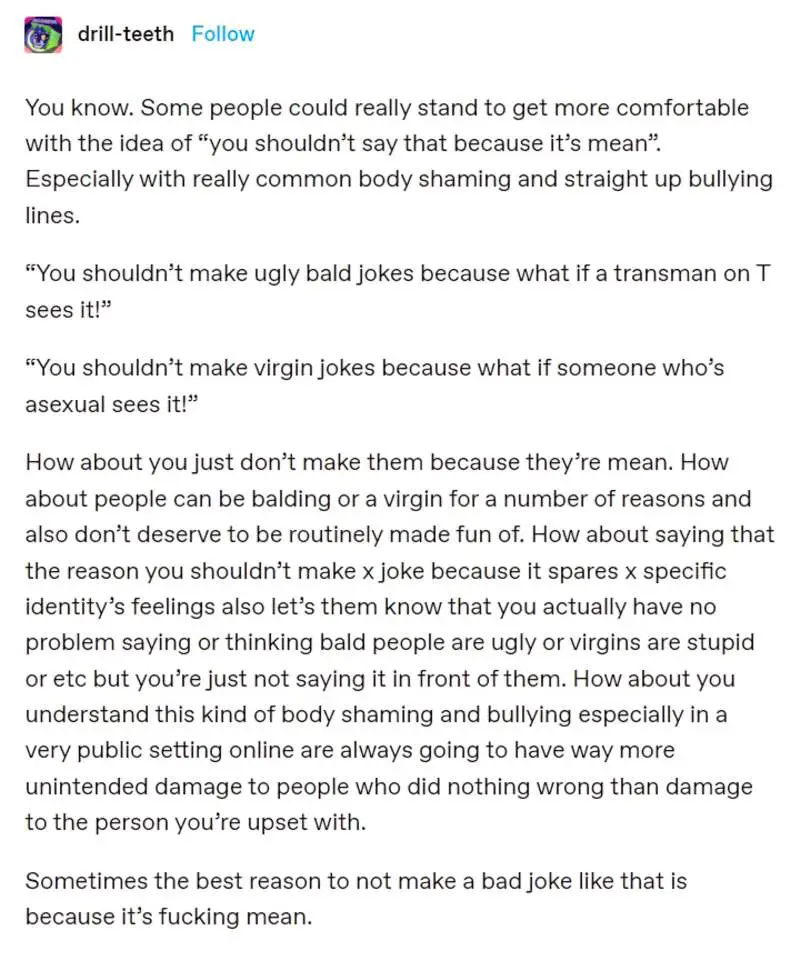

When authors cover the topic of bullying it can be super helpful to young readers, explicitly teaching what bullying is and how to recognise it for what it is. Even if we as adults have no further advice — I don’t consider myself qualified to give advice on how to deal with bullying — recognising bullying behaviour is a huge help to kids on the receiving end of it.

So, what does bullying look like? Some of these are obvious to neurotypical kids but in my opinion even neurotypical kids need explicit training on what bullying looks like. By putting these tactics into words, we are holding kids to higher standards. They then hold each other to higher standards.

- Touching someone in anger, or touching someone who doesn’t want to be touched

- Saying something nasty then putting ‘just joking’ on the end as a way of blaming others and demeaning the reaction of the victim

- Spreading untrue information about a person

- Threatening to tell an authority figure that a person has done something they have not

- Sharing true but personal information about a person

- Taking photos of someone without their consent, worse when shared, even worse via social media

- Mimicking the way someone walks/talks/eats etc

- Excluding someone because of skin colour/religion/culture and similar

- Microagressions are also a subtle form of bullying e.g. constant reference to someone’s difference from the wider peer group

- Barring someone from entering or exiting a space (commonly stairwells, toilets, shared play spaces)

- Practical jokes and pranks which are designed to humiliate someone, probably in front of a group

- Going into someone else’s bag/pockets/locker/desk without their consent

- Or more generally, messing around with someone else’s stuff with the intention of annoying them or shaming them

- Touching someone’s clothing, especially with the intention of exposing their body to others

- Provoking someone to anger, in general, hoping they will explode and get into trouble with teachers and parents

- Threatening to withdraw friendship unless someone does what you want them to do

- More generally, any behaviour designed to control another person. A lot of the bullying that goes on between girls mirrors exactly the abuse we call ‘coercive control’ when it happens in an adult relationship. Unfortunately, a history of falling victim to coercive control as a child/teenager primes someone to fall victim to it as an adult, too. (We can flip this, but we have to first name it, and teach it explicitly.)

HOW IS BULLYING TREATED IN CHILDREN’S LITERATURE?

“I live with a bear,” the story’s young narrator declares. The bear is loud, messy, uncouth, and very strong (too strong!). For some reason, his parents treat the bear like family, despite his protests. Why can’t they see? Then he runs into some bullies on the playground. When the bear ROOAARS with all her might and scares them away, he realizes that there are advantages to having a bear in the family. In a delightful twist, the narrator’s older sister (the bear) appears, telling him that she is NOT a bear. But if she is, HE is too–because two bears are even better than one!

Almost any story set in a school or a school stand-in will involve opposition between peers. Bullying is a common topic in children’s literature from chapter books onwards.

Adults know way more about how bullying works than a couple of generations ago. This can be traced through fiction (or ask any elderly person about their experiences of bullying in school).

Fictional bullies occurred frequently in school/boarding school stories, and it wasn’t treated as bullying, but more of a ‘character building exercise’, designed to prepare school aged children for a world in which they’ll be ranked in an adult hierarchy.

Today’s authors show a better understanding of the true nature of bullying, in which bullying is a social system, rather than a person:

All kinds of attitudes have changed, mostly for the better. Bullies were hated in Tom Brown’s Schooldays but now, as in Louis Sachar’s Holes, they are both villains and victims.

Amanda Craig, writing about the third golden age of children’s literature

We’re all doing better now, but still have a long way to go. How are adults, specifically adult writers, still getting bullying a bit wrong?

Bernice Buttman is tough, crass, and hilarious, and she just might teach you a thing or two about empathy in this debut reminiscent of The Great Gilly Hopkins.

When you’re a Buttman, the label “bully” comes with the territory, and Bernice lives up to her name. But life as a bully is lonely, and if there’s one thing Bernice really wants (even more than becoming a Hollywood stuntwoman), it’s a true friend.

After her mom skedaddles and leaves her in a new town with her aunt (who is also a real live nun), Bernice decides to mend her ways and become a model citizen. If her plan works, she just might be able to get herself to Hollywood Hills Stunt Camp! But it’s hard to be kind when no one shows you kindness, so a few cheesy pranks may still be up her sleeve. . . .

BULLIES WHO LOOK LIKE STEREOTYPICAL BULLIES

“There was a bully at Peter’s school and his name was Barry Tamerlane. He didn’t look like a bully” writes Ian McEwan in chapter four of Daydreamer. The explicit and direct message here is that “There’s no such person who looks like a bully.”

He wasn’t a scruff, his face wasn’t ugly, he didn’t have a frightening leer, or scabs on his knuckles and he didn’t carry dangerous weapons. he wasn’t particularly big. Nor was he one of those small, wiry, boney types who can turn out to be vicious fighters. At home he wasn’t smacked like many bullies are, and nor was he spoiled. His parents were kind but firm, and quite unsuspecting. His voice wasn’t loud of hoarse, his eyes weren’t hard and small and he wasn’t even very stupid. In fact, he was rather round and soft, though not quite a fatty, with glasses, and a spongy pink face, and a silver brace on his teeth. He often wore a sad and helpless look which appealed to some grown-ups and was useful when he had to talk himself out of trouble.

Ian McEwan, Daydreamer

I do wonder if there’s an unfortunate implicit message in here, though. When we describe the appearance of bullies, no matter how we do it, we’re conveying the implicit message that if you just study this hard enough, you’ll find you can typecast people according to how they look. ‘Bullies don’t look how you think they look… they actually look like this’, is one possible interpretation of the passage above, when I believe the intention is ‘You can’t pick a bully based on what they look like.’

McEwan does side with the young reader and does what most authors do: He acknowledges the fact that adults will never understand the complicated and subtle social dynamics of adolescents:

Of course, Peter kept out of the bully’s way, but he took a special interest in him. Barry Tamerlane was a mystery. On his eleventh birthday Barry invited a dozen boys from school to a party. Peter tried to get out of it but his parents would not listen. They themselves liked Mr and Mrs Tamerlane, and so, by the terms of grown-up logic, Peter must surely like Barry.

Ian McEwan, Daydreamer

MODEL VS IMPERFECT CHARACTERS

Authors sometimes set up a character web with ‘model’ children versus ‘imperfect’ children. By the end of the book, the young reader is supposed to have worked out for themselves who is in the wrong, and mimic the behaviour of the model children in real life. An example of this kind of book is Pigface by Catherine Robinson. The focus character learns a lesson when he breaks his leg playing football. While he’s away on the couch, a new boy joins the class. This new boy is preternaturally mature. When our focus character returns to school he realises he should stop calling Harry ‘Pigface’ because he probably doesn’t like it. He has also learned to stick up for other people, and not to judge others at face value. The reveal is that this cool new boy was bullied at his previous school.

This story for emerging readers does not attempt mimesis. It attempts (and achieves) a clear line between bullying and friendly behaviour. The reality is that a boy who was bullied at his previous school is likely to continue to be bullied at a new school, though bullying cultures do differ from school to school. It is possible to start with a clean slate in a new environment, though perhaps not quite so cleanly.

Blue is a quiet color. Red’s a hothead who likes to pick on Blue. Yellow, Orange, Green, and Purple don’t like what they see, but what can they do? When no one speaks up, things get out of hand — until One comes along and shows all the colors how to stand up, stand together, and count. As budding young readers learn about numbers, counting, and primary and secondary colors, they also learn about accepting each other’s differences and how it sometimes just takes one voice to make everyone count.

WRITING DEVELOPMENTALLY INCORRECT BULLYING

When do people start forming social hierarchies? As soon as they start interacting with groups of peers. But when does that real ‘mean-girl’ crap start happening?

“The mean-girl thing is happening much sooner than everyone realizes,” our elementary school counselor told me when I called to talk it through. “I see it all the time.”

The Washington Post

The parent who wrote this article found it first started happening to her daughter in fourth grade. I also have a daughter of that age (in NSW Australia it’s called ‘year four’) and I can confirm it started happening this year. What form does it take? For my daughter, it has involved social exclusion. Friend has a birthday, brings enough cupcakes for everybody, gives extra cupcakes to her ‘besties’, refuses to give cupcake to one girl in particular as some kind of social punishment. It’s easy to almost laugh at this ridiculous example, but if this happened to us in our workplace, we’d be equally wounded. Apart from blatant social exclusion:

The most common ways girls ages 8 to 12 bully is by mocking, teasing and calling people names, says Cosette Taillac, a child and adolescent therapist

The Washington Post

Though that article focuses specifically on the types of bullying that goes on among girls, it strikes me that at 8-12 years old, there’s no significant difference between how girls and boys bully others. Boys use this same strategy of ‘mocking, teasing and calling people names’. However, the nature of these names might be different. Because of a cultural emphasis, girls are more vulnerable to commentary about physical appearance:

“Girls at this age are extremely conscious about how they look in relationship to others,” Taillac says. “Any way they look ‘different’ is a potential target. This goes beyond weight — it can also be about being taller or shorter, skin color, or even about things like having freckles or pimples.”

The Washington Post

(No one is saying boys aren’t also picked on due to how they look; the difference is that all girls are judged based on their looks no matter what they look like, whereas physical appearance only comes into it for boys when the boy does actually fall outside the ‘accepted norm’, and ‘the norm’ is wider for boys. Which is of course no comfort to boys who do fall outside the accepted norm for boys. And boys are getting more judgemental about each other’s appearance, unfortunately. Living in the exact same culture, it’s getting worse for girls as well.)

On a more positive note, this form of bullying has all but disappeared by senior high school.

This opinion piece written by a teenager echoes something I’d already noticed myself:

In my school, most people like each other! We might not like the same brands or bands, but that doesn’t mean we have a burning desire to watch those more traditional or popular fail. (That would be middle school.)

While this HuffPost article is painting too broad a stroke with an inflammatory headline about not liking YA novels in general (there are many different genres within that category), the writer is pointing out that bullying takes on a different form altogether once students move through high school. (But it doesn’t disappear completely.)

HOW BULLYING CHANGES DURING ADOLESCENCE

Bullying among the 8-10 year old set looks completely different from bullying in senior high school. This needs to be reflected in stories.

I Study The Psychology Of Adolescent Bullies is about Donald Trump but offers an insight into how bullying works at each age. The subheading sums it up: Kids who dominate other kids are often popular — for a little while.

Below is the reason given for why middle school is terrible for bullying, though I grew up in a country where middle school was often attached to the primary school — no major reshuffling necessary. I don’t know how the social dynamics are different in those cases but:

Although bullies are never liked, they are popular in certain situations. Our research shows that bullies initially become “cool” during their first year in middle school. We think that this link between bullying and popularity is strengthened by the collective uncertainty associated with the transition to middle school. As youth are trying to acclimate to the new setting, many worry about their own social standing and ask: Where do I fit in? Who should I hang out with? When the future is uncertain, it is vital to know not only where one fits, but also who is in charge. Dominance hierarchies help group members find their places and form alliances, and bullying is among the most primitive ways to establish dominance.

I have noticed in some stories, especially those on TV, middle school level bullying continues long past its due date. By the time students are about 15, explicit, racist or un-woke bullying behaviours have morphed into social dynamics far more subtle. But what does it turn into?

Our research on middle-schoolers also shows that the popularity of bullies wears off after the transition period. That is, after the first year in middle school, bullies’ popularity gradually decreases. […] When a young child is questioned whether he ate the last cookie (even when there are crumbs on his lips), the immature response is: “I didn’t do it.” Children deny the act before they learn that it is socially beneficial to admit the wrongdoing but deny any negative intent. Teens tend to become even more skilful and elaborate on various mitigating circumstances, such as not turning in their homework due to illness or because they were helping an ailing grandmother. These accounts reduce the likelihood of punishment and facilitate forgiveness.

If bullying is still going on in senior high school, it is insidious and covert and ridiculously difficult to deal with. It can usually be denied completely. ‘Social exclusion’ looks a lot like, simply, exercising your right to choose your own friends.

An Indian American girl navigates prejudice in her small town and learns the power of her own voice in this brilliant gem of a middle grade novel full of humor and heart, perfect for fans of Front Desk and Amina’s Voice.

As the only Indian American kid in her small town, Lekha Divekar feels like she has two versions of herself: Home Lekha, who loves watching Bollywood movies and eating Indian food, and School Lekha, who pins her hair over her bindi birthmark and avoids confrontation at all costs, especially when someone teases her for being Indian.

When a girl Lekha’s age moves in across the street, Lekha is excited to hear that her name is Avantika and she’s Desi, too! Finally, there will be someone else around who gets it. But as soon as Avantika speaks, Lekha realizes she has an accent. She’s new to this country, and not at all like Lekha.

To Lekha’s surprise, Avantika does not feel the same way as Lekha about having two separate lives or about the bullying at school. Avantika doesn’t take the bullying quietly. And she proudly displays her culture no matter where she is: at home or at school.

When a racist incident rocks Lekha’s community, Lekha realizes she must make a choice: continue to remain silent or find her voice before it’s too late.

COMMON MISCONCEPTIONS ABOUT BULLYING

- Bullying is a problem that bullying people have. It does not follow that someone targeted by a system of persistent bullying is the one doing something wrong.

- Children and teens need friends. Friends aren’t just ‘the icing on the cake’.

- In order to be happy, children don’t need a wide circle of friends. Sometimes all it takes is one friend. The difference between no friends and one friend is like night and day.

- Unkind behaviour toward children without social status is rewarded with social capital and elevated social status, because it highlights the status differential.

- It is not easy — in fact it is an act of rare and unusual bravery — to step in and defend someone with low social capital. Defending a low-status child is like touching someone with “cooties,” so bystanders rarely step in.

- A child at the bottom of the social ladder becomes “untouchable.” Even if that child has a delightful personality and loads of friends elsewhere, in a social system in which she lacks social capital, she is not likely to acquire friends. Take away point: a child can have loads of friends in one situation and none in another, because ‘untouchable’ cultures can pop up anywhere if not kept in check.

- Children with status erroneously believe that the reason untouchables have no social status is because they are repulsive, but in truth, it is precisely the reverse. The lack of social status is what makes an untouchable appear repulsive.

- Adults are no more likely to sacrifice their own social capital to stop bullying than children are. Adults don’t magically go through a character arc in which they are immune to all this crap. Most of us quietly become part of the system.

- When adults instruct kids to simply ‘walk away’ from bullying, we are indoctrinating them into this system. Parents justify this by going back to the concept of ‘freedom’. ‘My child must be granted the freedom to choose her own friends’.

—Happiness and the Pursuit of Leadership

Can we end the whole “you attract who you are” myth? There are abusive, terrible and mediocre people who latch on to vulnerable, kind and generous folks.

Another myth to abolish: You don’t have to “love yourself” first in order to be worthy of love in return. You are worthy of being loved, of being safe and well-cared for regardless of how you feel about yourself.

@femmefeministe

BEWARE CHILDREN’S LITERATURE WHICH VALORISES THE BULLY

Rowling … makes heroes of bullies. The Marauders are painted in an admirable light even though two of them meet a strange kid, immediately decide they don’t like him, and then bully him for the next seven years. Sirius still calls him by the same stupid name some twenty years later.

@indigoace, 8:35 AM · Aug 1, 2021

RELATED RESOURCES ON BULLYING

- A New Way To Reduce Playground Bullying

- Bullies and Bullying In Kids’ Books

- For more on coercive control, this podcast (actually the entire series) is excellent.

- Judith Staff on the difference between ‘resilience’ and ‘resignation’ is important.

- Bullies Use Their Dominance and Manipulation In All Areas Of Life, Study Reveals from The Independent (possible paywall)

Amy Alkon coined the term ‘social greed’ to describe someone’s unwillingness to risk their own social capital without an anticipated return on investment.

PE – a History of Violence: Matthew Sweet asks why physical education was the only school subject in which humiliation was considered part of the learning process at Archive on BBC4

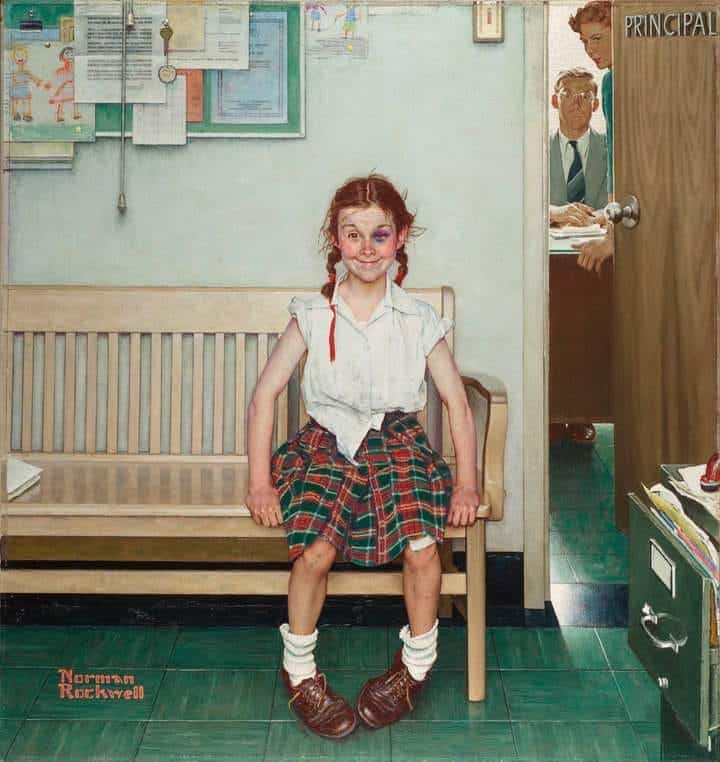

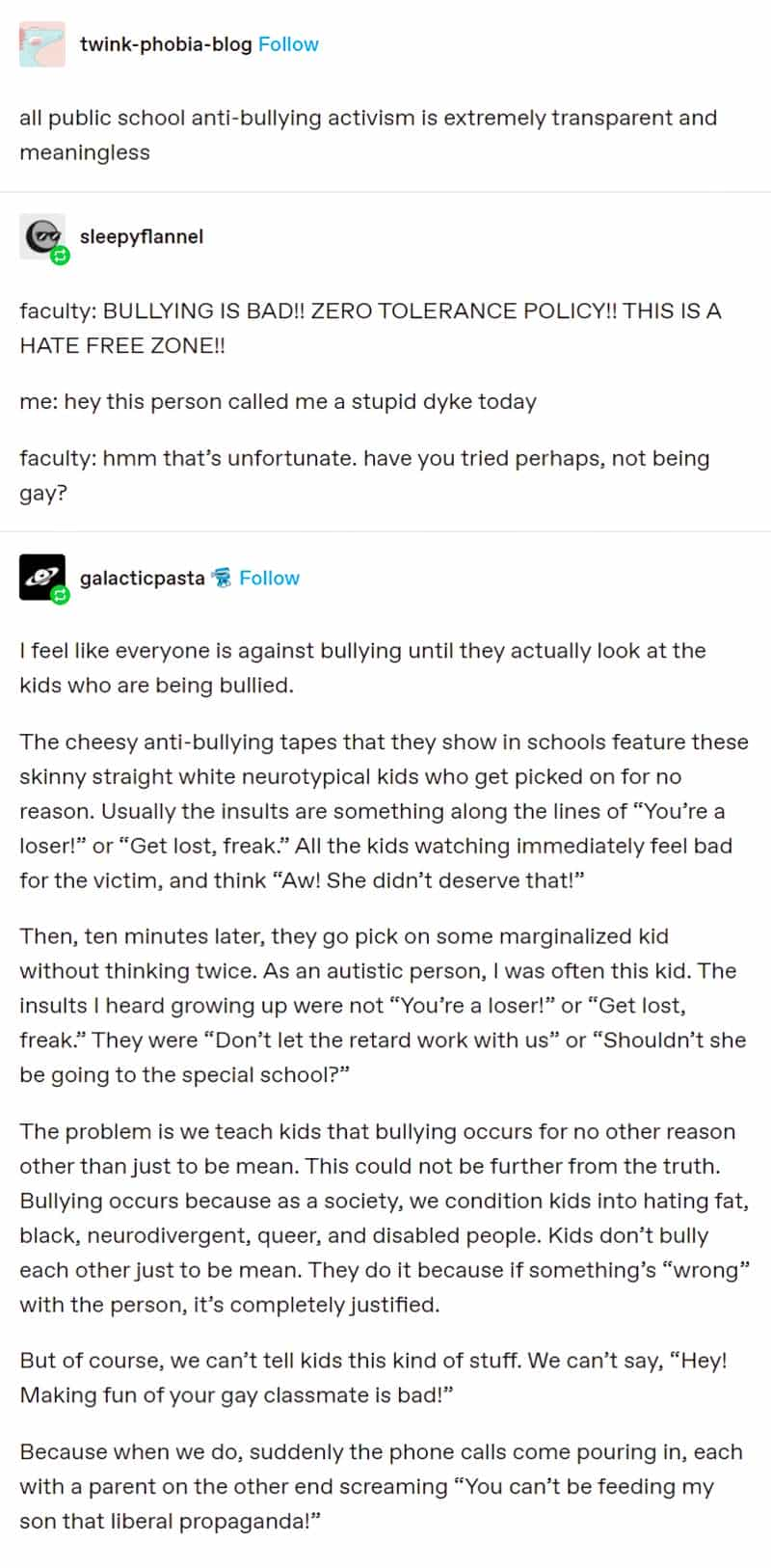

THE NORMATIVE FACE OF BULLYING VICTIMS

THE ARGUMENT FOR MAKING BULLYING A CRIME

“We need to stamp out bullying “

Stamping out bullying won’t work because, generally, people don’t want to face up to a bully and hold that bully accountable.

Bullies need to know it’s about more than moral wrongdoing and that their actions will not be tolerated.

The more I think of it, the more I believe that BULLYING needs to be made a crime.

In the UK, BULLYING is currently NOT a crime. Certain acts within bullying are, for instance harassing, stalking, assault, hate crime.

But bullying is not.

This is, to my mind, ludicrous.

We ALL know what bullying looks like.

We ALL know what bullying feels like.

We ALL know the harm that is caused is significant.The long term effects of bullying. The depression, isolation, despair and suicidality.

But it’s not a crime.

We know what BULLYING looks like in the workplace, in schools, in sports, in religious settings and in the home.

And we ALSO know how difficult it is to hold bullies accountable.

The fear of confronting a bully and the repercussions.How difficult it is to make them stop.

We know that BULLYING is about power and control. There is a power imbalance between the victim and the bully. A bully knows they won’t be challenged and is therefore able to continue, often, unimpeded.

A bully will often attract similarly-minded individuals who continue the work of the bully. A bully rarely works alone. Yet victim is expected to build resilience and to defend themselves against the bully whilst the system does nothing to intervene.

If we’re talking about domestic abuse and raising awareness of the harms caused by violence/abuse/coercive control in the home, we can not ignore abuse that occurs outside of it.

“Bullying needs to be made a crime”

“But bullies are often being victimised by others. If we punish the bully we are really punishing a victim.”

This isn’t an acceptable response to bullying and yet I hear it all the time.

Originally tweeted by Coercive Control & Recovering From Trauma (@CCCBuryStEd) on May 14, 2021.