“Brokeback Mountain” is a heart-wrenching short story in part because of its density and one-sitting experience. This is an amazing feat. I mean, it’s so short, right? Normally you need the build-up of an entire novel to induce such strong reactions in readers. Or at least the soundtrack, cinematography and expert acting of a film. Annie Proulx’s short stories have the wordcount of short stories but the emotional resonance of epics.

I’m reading this story in what is now called Brokeback Mountain and Other Stories. Here are the other stories:

The Half-Skinned Steer

The Mud Below

Job History

The Blood Bay

People In Hell Just Want A Drink Of Water

The Bunchgrass End Of The World

Pair a Spurs

A Lonely Coast

The Governors of Wyoming

55 Miles To The Gas Pump

Brokeback Mountain

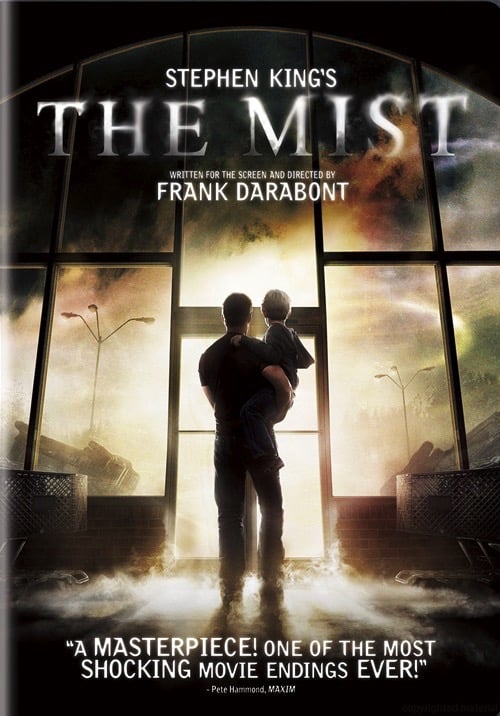

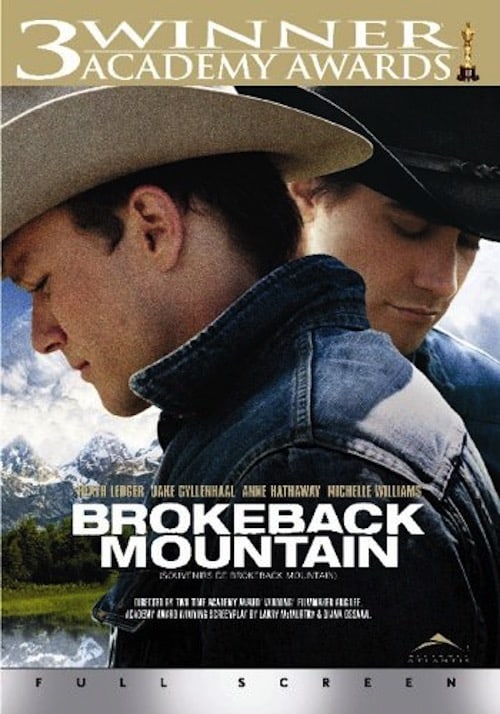

“Brokeback Mountain” was published in the New Yorker in 1997, but came to most people’s attention in 2005 when it was adapted for screen and won critical acclaim.

Read the full text at The New Yorker.

The Title

Proulx has a definite talent for selecting those place names that are most likely to reveal the psychology of her characters or inventing others which have such a ring of truth in them that they could easily have been actual names for the places she describes. The name Brokeback Mountain, for instance, resonates with a multiplicity of echoes, from images of backbreaking labor and harsh conditions of life to the necessity of bending under the weight of submission to the so-called “norm” and the permanent threat of having one’s back “broken” by those who won’t put up with any deviation from this norm.

“The Influence of the Annales School”, The Geographical Imagination of Annie Proulx, Durrans

What Kind Of Story Even Is This?

Australia’s SBS social media team recently Facebooked a re-screening of the film Brokeback Mountain, describing it as, and I quote, ‘Ang Lee’s tender love story’. I didn’t write the thing but even I have two problems with that. First of all, for all a screenwriter/director brings to a story, the story ‘belongs’ to the person who created it. Ang Lee adapted it but bear in mind, Annie Proulx made something from nothing at all. Once a story gets adapted for screen, kudos tends to transfer to the people who brought it to screen and the original author probably gets some extra visibility too, but compared to the self-congratulatory movie industry, writers are basically invisible.

Second, nothing about “Brokeback Mountain” is ‘tender’, unless you forget the beating and murder of the gay man, or the almost-maybe-anal-rape of the wife. ‘Tender’ is not a word generally associated with the work of Annie Proulx. Unforgiving, brutal, tragic… now those are adjectives I can go for.

I suspect this is all part of why Annie Proulx wishes she’d never written Brokeback Mountain:

[T]he problem has come since the film. So many people have completely misunderstood the story. I think it’s important to leave spaces in a story for readers to fill in from their own experience, but unfortunately the audience that “Brokeback” reached most strongly have powerful fantasy lives. And one of the reasons we keep the gates locked here is that a lot of men have decided that the story should have had a happy ending. They can’t bear the way it ends — they just can’t stand it. So they rewrite the story, including all kinds of boyfriends and new lovers and so forth after Jack is killed. And it just drives me wild.

This says something wider about our expectations for movie endings. It’s baffling, because although we think Hollywood loves happy endings, although we expect happy endings, when you take a survey of Hollywood stories, actually there are far fewer genuinely happy endings than you probably think. The truth is, audiences don’t need happy endings, even the most basic of Hollywood consumers who go for the popcorn:

Down-ending films are often huge commercial successes….For the vast majority doesn’t care if a film ends up or down. What the audience wants is emotional satisfaction–a Climax that fulfills anticipation….Who determines which particular emotion will satisfy an audience at the end of a film? The writer. From the way he tells his story from the beginning, he whispers to the audience: “Expect an up-ending,” or “Expect a down-ending” or “Expect irony”. Having pledged a certain emotion, it’d be ruinous not to deliver. So we give the audience the experience we’ve promised, but not in the way it expects.

– Robert McKee

In the same interview, Proulx tells us what “Brokeback Mountain” is intended to be about:

They can’t understand that the story isn’t about Jack and Ennis. It’s about homophobia; it’s about a social situation; it’s about a place and a particular mindset and morality. They just don’t get it. I can’t tell you how many of these things have been sent to me as though they’re expecting me to say, Oh great, if only I’d had the sense to write it that way. And they all begin the same way — I’m not gay, but … The implication is that because they’re men they understand much better than I how these people would have behaved. And maybe they do. But that’s not the story I wrote. Those are not their characters. The characters belong to me by law.

Annie Proulx has astutely picked that gender is playing a part here. I think gender plays a part in who gets plaudits and accolades in Hollywood, too. Rarely does a film adaptation of a film come out in which the audience is not hyper-aware that the story belongs to Stephen King.

On the subject of gender:

At the time, “Brokeback” was as stunning as it was heartbreaking. Was it more stunning that it had been written by a woman? Or perhaps less? It seemed that the editors, or Proulx herself, wanted us to consider the question: in the center of the second page of the opening spread, we saw a cartoon portrait of Proulx, gender-ambiguous at first glance, with the following caption:

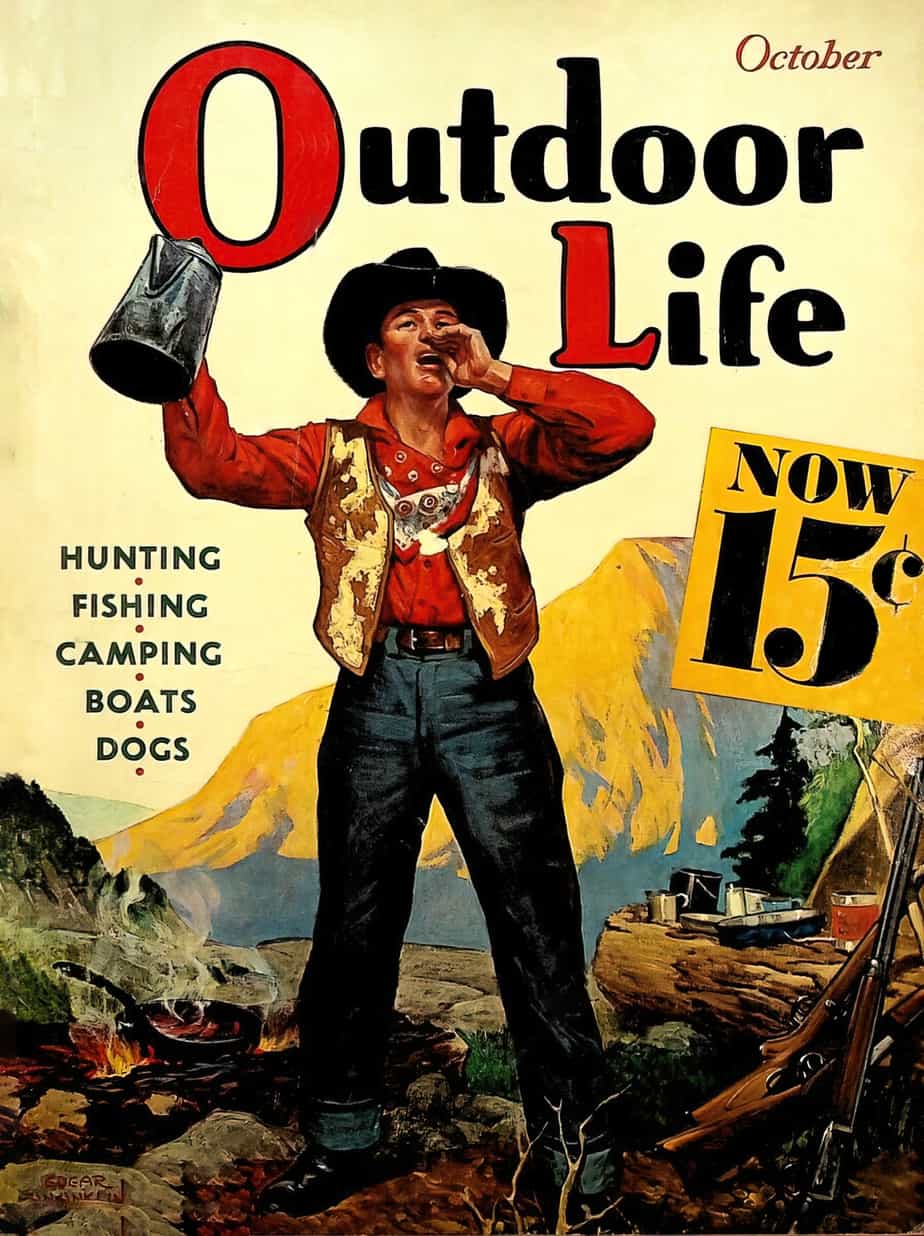

The author’s first stories, twenty years ago, were all about hunting and fishing – “hook-and-bullet material” – written for a men’s-magazine editor who thought he couldn’t publish a contributor called Annie. He suggested “something like Joe or Zack, retrievers’ names,” the author recalls. The compromise was initials: E.A. Proulx. The “E” somehow stuck. (The author won the Pulitzer Prize as E. Annie Proulx.) The author is now sixty-four, and “Brokeback Mountain” is the first story published by just Annie.

In the late 1970s, Proulx had to pretend to be a male author to publish stories for a male audience; in 1997, writing an erotic gay-male love story for the intellectual set, she came out, officially, as a woman. Was October 1997 a moment when we decided that a woman could write whatever she damn well pleased (because look how well she’s doing it)? Or was the revelation of Proulx’s gender a way of making a groundbreaking story (for the New Yorker, anyway) go down easier?

Do we ever really “forget” the author? Does she ever truly recede when we are reading gender-crossing works? Do we necessarily want her to?

The Great Divide: Writing Across Gender from The Millions

SETTING OF BROKEBACK MOUNTAIN

- 1960s Wyoming. Jack and Ennis meet in 1963

- Their first job together is at a sheep operation north of Signal. Signal is a fictional place. The movie was filmed in Cowley, Alberta. “The summer range lay above the tree line on Forest Service land on Brokeback Mountain.”

- Jack Twist raised in Lightning Flat up on the Montana border

- Ennis Del Mar was also raised on a small, poor ranch but from around Sage, near the Utah line

- There’s no real safety net for poor kids. Ennis is unable to finish highschool due to losing his parents and poverty.

- Life-shattering levels of homophobia

- Hyper-masculinity is revered

- These two men, used to living as closeted gay men, have been given a job which requires them to leave no trace of themselves. While tending the sheep and keeping ‘predators’ (read: violent homophobics) away they must light no ‘fire’ (read: keep their true feelings to themselves). “Roll up that tent every morning in case Forest Service snoops round.”

- Rodeo life is a big part of the culture. Jack in particular is fascinated with this. From “The Mud Below” we know that Annie Proulx considers the rodeo symbolic of hyper masculinity. But rodeo life is changing. It’s turned into a highly competitive sport — much like rugby went from being a pastime to an industry in my home country at around the same time. This means you need money behind you to make any money out of it yourself.

- A Basque American guy helps the white men load up the mules. Today there are about 60,000 Basque Americans. Wyoming is not a particularly likely place to find someone of Basque descent — most have settled in other states.

STORY STRUCTURE OF BROKEBACK MOUNTAIN

When analysing the structure of a story, the first thing I usually do is work out who the main character is. But every now and then you don’t get a main character — as Proulx explained above, this is about a society, not a single person. Nevertheless, to say anything about a society a writer needs to zone in on individuated characters. Here we have co-heroes Ennis Del Mar and Jack Twist.

SHORTCOMING

Being gay in a homophobic society is pretty much all that needs to be said here.

DESIRE

Terrified of living true to themselves, Ennis and Jack want to live as straight manly-men but their wishes are scuppered by the inconvenient reality of falling of love with each other.

OPPONENT

In any love story, the love interest is the number one opponent, but I don’t want to call this a love story first and foremost. This is a hate story. Ennis and Jack’s biggest opponents are the unnamed men who would kick the shit out of them if they knew what they’d been up to up there in those mountains.

Ennis’s main opponent is his dead father, who he suspects of beating a gay man to death and showing it to him and his brother many years ago when they were very young and impressionable.

There are also living representations of his hate-filled father, such as the employer who saw them through binoculars and John Twist. These people represent a hostile wider society, which is the over-riding opponent.

PLAN

Jack can’t leave his wife Alma and two young daughters. He is also terrified of being killed.

Ennis wants them to both leave their families (he’s happier to leave his wife and their son — it seems he’s married her mainly for the prospect of inheritance). He has plans for them to run a ranch together. He’ll use the money he’s sure to get out of his father-in-law to buy one and they can lead a good life together running it.

Jack’s counter plan is for them to meet regularly on the mountain whenever they can get away from their regular lives.

BIG STRUGGLE

The confrontation, where Ennis and Jack finally voice their dilemma. One of them is prepared to sacrifice physical safety to live with his male lover; the other is not.

ANAGNORISIS

There is no anagnorisis. Not in the sense that Ennis finally breaks free of his fear and lives a happy, fulfilled life.

NEW SITUATION

Convinced that Jack has been killed in a hate crime, he continues to live closeted and in fear.

TECHNIQUES OF NOTE

Thumbnail Character Sketches

At first glance Jack seemed fair enough, with his curly hair and quick laugh, but for a small man he carried some weight in the haunch and his smile disclosed buckteeth, not pronounced enough to let him eat popcorn out of the neck of a jug, but noticeable.

Annie Proulx, quoted in Super Easy Ways To Create Characters For Short Stories, because Proulx is a master of the thumbnail character sketch.

Brokeback Mountain

COMPARE AND CONTRAST

If you want a tender love story try Mary and Max, an Australian claymation film about a blossoming pen pal relationship.

Lonesome Dove stands out these days for its absence of the homoerotica which would surely be present in an outback environment with only men around. There is some similarity between “Brokeback Mountain” and Lonesome Dove, though, because it’s about two men whose relationship with each other eclipses anything else in their lives.

For another film about a forbidden same-sex relationship which spans years of absence, there’s also Lovesong (2016) directed and written by So-yong Kim. While outwardly similar to Brokeback Mountain, the intensity of feelings assumed to exist in the characters never crosses over into the audience. This is largely due to the passivity of one of the women.

FOR FURTHER INVESTIGATION

Brokeback Mountain: The Foolscap, Story Grid podcast

STORY TO SCREENPLAY BOOK

Brokeback Mountain: Story to Screenplay by Annie Proulx, Larry McMurtry, Diana Ossana (2005). Allows you to compare the book and screenplay. Includes the story and script as well as essays by each of the authors. Annie Proulx’s essay is called “Getting Movied”. The final line: “an accumulation of very small details…give the film authenticity and authority”. She names the speckled enamel coffeepot as an example.

The World To Come is another film which started out as a short story. The short story, by Jim Shepard, is about a community rather than individuals. Specifically, the story is about the violence of patriarchy which limits the freedoms of women in 18th century upstate New York.

However, when adapted for film, the story now homes in on the two characters, rounding them out, and turning it into what can only be described as a ‘love story’. Brokeback Mountain suffered the exact same fate and it seems filmmakers haven’t learned. Perhaps this is because of a wide accpetance that adaptations of short stories are separate products from the original short stories, and that film-goers want something different from a screen experience than your typical short story reader.

In this episode, we discuss “Brokeback Mountain” by Annie Proulx. What can we learn from the quiet voice of this story? How does the narrative voice represent the characters? How can the setting determine the voice of the story? How can a voice embody the whole story? Can we learn from the underlying story of characters who can’t have what they really want?

Alternate version of the story: “Brokeback Mountain” by Annie Proulx

Why Is This Good? podcast

The researcher, himself in a MOM (mixed-orientation marriage), was surprised to find how long the process of coming out was for the gay men married to women, and also surprised at how often the wives experienced what they described as a momentary epiphany of acceptance.

The wives commonly felt what has been called (by P. Boss, 1999) ‘ambiguous loss’, ie. the sense that your partner is physically present but psychologically absent.

The men who realised they were gay before meeting their wives and experienced sex with men before settling down with a woman had an easier time of marriage with a woman than the men who didn’t realise they were gay until after marrying a woman.

When this realisation happens earlier in a marriage it is easier for both parties than when it happens after decades.

In an interview with The Sunday Times, the 40-year-old actor was asked if he thought there’d be a “different reaction” to two straight actors taking on the romantic leads today.

Jake Gyllenhaal thinks Brokeback Mountain broke ‘stigma’ of straight actors playing LGBT+ roles