The Bridges of Madison County is a 1995 American one-true-love romance. The film is based on a 1992 best-selling, terribly written novel by Robert James Waller.

Stephen King gives the novel a roasting in his well-known book On Writing. Almost everyone who wants to be a writer seems to have read King’s writing book, part autobiography, part how-to guide. In the appendix, King includes a list of excellent novels and a list of terrible ones. He says writers must read bad writing before fully comprehending what makes good novels good. I feel Stephen King is too powerful to be so callous about others. But here’s what I’ve also noticed: Most powerful people came from nothing, and forever see themselves as ‘outside the establishment’. For them, there’s no epiphany in which they realise, “I’m big cheese now. I’d better be careful who I roast.”

Then again, Bridges of Madison County did sell 60 million copies. Maybe if you sell that many books, you’re a peer of Stephen King.

Is ‘Bad Writing’ Simply ‘Screenplay Writing’?

I have nothing like Stephen King’s clout. So I’ll tell you this. I picked up Robert James Waller’s novel Bridges of Madison County at a second-hand store for fifty cents. I took it home and sat down to read it. If Stephen King made it all the way through that novel he did better than me. I couldn’t make it past the first five pages. I’m inclined to absorb the style of whatever I’ve been reading lately, and the prose was so cringe I was worried it would infect my own prose. The guy wrote the novel in 11 days and it shows.

The conventional wisdom in Hollywood is that it’s easier to make a good movie from a bad book than from a great one. That’s probably true. No one has ever gotten The Great Gatsby right. A Confederacy of Dunces has allegedly driven some who’ve tried to adapt it mad. Did you hear that James Franco made a film version of As I Lay Dying? Exactly.

Phillip Martin, Arkansas Online

The book is written as badly as a screenplay. Ergo, it makes for a great screenplay. (Screenplays are work documents, never intended to be enjoyed for their line-level beauty.)

Who Gets To Be A ‘Good Writer’?

Stephenie Meyer is another romance writer whose best-selling vampire novel Twilight is frequently held up as an example of poor writing. Readers who love her work (mostly teenage girls and adult women) are assumed incapable of seeing bad prose for what it is. This isn’t true. Many of Twilight’s biggest fans write sophisticated think-pieces about the series’ problems, ideological and stylistic. Many will likewise point out that the prose becomes better as the series progresses.

There are clearly gender issues affecting pop criticism of pop books. There are also publishing industry issues at play. Why wasn’t the first Twilight book better edited? Why aren’t publishers spending more on editors in general? Well. Why aren’t readers spending more on books?

See also: Films That Centre Characters Over 40

Genre Blend of Bridges of Madison County

The editors at Story Grid did an episode of The Bridges of Madison County. They consider this story an example of a Courtship Love story.

What Makes A Good Story?

There are many aspects to a great story. All aspects interrelate, but beautiful prose is just one thing, and maybe not even the most important thing to people who read one or two books a year.

Plotting and characterisation are separate from a novel’s line-level beauty. When ugly prose is adapted for film, the prose is no longer an issue. Now other aspects are allowed to shine (or fall flat). At least, this is the case when adept actors are cast in major roles. Meryl Streep and Clint Eastwood do a marvellous job of elevating cheesy dialogue of The Bridges of Madison County. They also share superb onscreen chemistry.

Clint Eastwood clearly saw the adaptive potential of this story. He produced it, directed it and starred in it. The movie is a particular type of satisfying. But because the line-level cringe has all but gone in the film, other issues reveal themselves.

On Setting and Authenticity

While audiences will accept films made with CGI or filmed against backdrops inside Hollywood studios, there’s a special appreciation reserved for movies filmed on site in off-the-beaten-track locations.

The Bridges of Madison County is authentic to its setting. True Grit is also set partly in Iowa, but The Bridges of Madison County looks a lot more like the actual place, being filmed there and all.

I’m giving this old story some fresh attention because three decades later audiences continue to enjoy the film, and theatres around the world continue to adapt the story for stage.

Paratext

Before it became a film, the novel was also sold as Love in Black and White. Here are a couple of the covers.

The Politics of ‘True Stories’

Readers of the novel are told they are embarking upon a novelization of a true story. The Bridges of Madison County is in fact fictional, though the author realised after he’d written Francesca that he’d had his own wife in mind.

When audiences are told a story is true, we may not believe the story is entirely true (no story ever is) but it changes our response to it. If we hear (or read) a story thinking it’s true(ish) and then learn it’s not true at all, isn’t that the same feeling as having been told a lie?

Australian film Wolf Creek pulls the same swifty. There’s nothing true about it. The filmmakers cash in on the horrific ‘backpacker murders’ committed by Ivan Milat in the 1990s, which took place in a completely different part of Australia under completely different circumstances from the events which unfold in Wolf Creek. The connection is: Sadlstic man abducts young travellers and murders them.

This isn’t a new thing. Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Facts in the Case of M. Valdemar” was published in 1845. A mesmerist puts the dying M. Valdemar into a mesmeric state for seven months and monitors him with a team of doctors. When first published, many readers read ‘facts’ in the title and believed was a scientific report.

When is it okay to preface a story with ‘facts’, or ‘based on true events’? After all, every single fictional story is inspired by something or other.

In the case of Bridges of Madison County, the author clearly wants us to approach this story as a work of realism. Rather than working harder to establish the target mood, he takes the cheat’s way out.

Fortunately, the movie is more honest with us. There’s no ‘based on a true story’ at the beginning of the film adaptation. The filmmakers establish realism by shooting on location.

See also: Episode 9 of the Then Again Podcast, “Based on a True Story”: the ethics of telling true stories in movies. When you see the words “based on a true story” in the opening credits of a film assume that’s Hollywood-speak for “mostly lies”! Using the film “Green Book” and the discussion its Oscar-winning generated as a springboard, in this episode Ken and Glen delve into truth, seeming truth, and cinematic responsibility in film.

What Happens In The Bridges of Madison County?

[SETTING] It is the hot and humid summer of 1965 in Iowa. Francesca Johnson is a married housewife with two teenage children and a farmer husband. Although she grew up in Italy, and came to America as a war-bride, she wasn’t picturing Iowa when she emigrated. As a young Italian teacher she had romanticised America.

When we first meet Francesca she is busying herself in the kitchen, providing dinner for her family while listening to old, romantic music. Her teenage daughter enters the kitchen and immediately changes the station to 1960s pop music. [FAMILY OPPONENT] Francesca can’t be bothered with an argument, so sacrifices her own pleasure. She stares out the window while her family chows down. We understand Francesca has her own hopes and dreams… well, dreams, anyway. [SHORTCOMING] The hopes may have gone.

The following day, Francesca’s husband and children attend the Illinois state fair. Francesca plans to spend four days alone at the house having a kind of housewife holiday. She has only the dog for company.

But soon after Francesca’s family leave, divorced professional photographer Robert Kincaid [ROMANTIC OPPONENT] happens to turn into the Johnson farm. He’s on assignment from National Geographic magazine to take photos of local bridges. He asks Francesca for directions to Roseman Bridge.

Francesca is initially wary of the handsome stranger, but she’s terrible at giving directions, so agrees to show him to Roseman Bridge herself. Note that she mentions a fork in the road. This is part of the symbolism in which Francesca will soon be required to make the biggest decision of her life.

Over the course of the hot afternoon the pair enjoy various drinks (soda, iced tea, eventually moving on to alcohol). Robert Kincaid accepts an invitation for dinner and plays the role of the hippie, attentive sage. Francesca opens up to Robert and enjoys his unfamiliar form of communicative masculinity. He even offers to help her prepare vegetables in the kitchen, an emasculating task.

Robert spends the following day photographing bridges. While at a diner he notices the poor treatment doled out to a woman who has become talk of the town for having an extramarital affair. [SOCIETAL OPPONENT]

He calls Francesca on a pay phone and offers to cancel the plans they made to go to a bridge together in a different town. If Francesca is seen with him, her life will be changed forever. Francesca refuses to cancel their date. The pair sleep together.

[PLAN] Francesca buys a new dress which better reflects her new self-image as a sexually desirable woman rather than just a mother.

Francesca and Robert spend a beautiful few days together, mostly relaxing in each others’ company, sometimes arguing about how to live a good life: Francesca thinks you need a family to be happy, whereas Robert insists he loves people more generally, and needs no one in particular. He also rejects Francesca’s accusation that he goes from place to place seducing women, leaving them in emotional disarray. He insists that he has never met a woman like Francesca before.

Robert invites Francesca to run away with him and claim her once-in-a-lifetime chance of travelling the world. Robert argues that Francesca’s husband and teenage children will be okay without her because people move on, and didn’t she argue that her kids don’t appreciate her anyway? While struggling with this choice, Francesca and Robert are interrupted at the house by one of Francesca’s chatterbox friends who has popped round for a chat about the usual mundane problems around being a wife and mother. Robert hides upstairs until Francesca can get rid of her.

Francesca gets as far as packing two suitcases, but ultimately decides against abandoning her family. [CHANGED PLAN] Although her teenagers don’t appreciate her, she figures they still need her. [MORAL DECISION]

Robert won’t be leaving town for another few days, which gives Francesca extra time to agonise over her final decision.

Francesca’s family return from the fair. She runs into town with her husband on errands. The last time she sees Robert, she’s in the truck with her husband at the wheel. Robert Kincaid is stopped at the traffic light right ahead. He is silently asking her one last time if she’s sure. Francesca resists the strong urge to rush to Robert.

She spends the rest of her life faithful to her husband. Now that she’s had the experience of falling in love with another man, she understands how it’s possible to be in love with your husband as well as a hot passion with someone else. [ANAGNORISIS] She has fresh empathy for the ostracised woman of the township, and goes out of her way to make friends with her.

The audience considers the tragedy of living just one life. Every decision we make cuts off another possible life, and the older we get, the more clear to us our decisions become.

[NEW SITUATION] Many years pass. Francesca’s husband grows sick and dies. Francesca fills three notebooks with details of the four-day love affair she had with Robert. She wants her children to really know her, but not until after she’s dead and gone.

She story opens soon after Francesca has died. Her adult son and daughter return to the homestead to put their mother’s affairs in order. This story, set in present-day 1990s, bookends the 1965 flashback, which is a story-within-a-story.

Eager to understand why their mother has requested her ashes be thrown off a bridge, Francesca’s middle-aged daughter reads the journals from cover to cover. The daughter understands that she’s in an unsatisfactory marriage herself, and decides not to return to her lousy, unfaithful husband. In contrast, the son realises how lucky he is, and returns with fresh love to his own wife and young family.

Symbolism

There’s nothing subtle about the symbolism of this story. (That’s not a criticism, just a fact.)

This Iowa classic is perhaps surprisingly one of the best selling books of the 20th century, having sold over a whopping 50 million units. It tells the classic story of star-crossed lovers in 1960s Madison County, IA. It’s not far from the state’s epicenter of Des Moines, but still decidedly rural. Italian transplant Francesca has a family, but remains lonely, and Robert travels into town as a photographer to shoot the area’s famous covered bridges. You can imagine what happens next. It’s an excellent story of enduring love, made even more real when you’ve seen the covered bridges in person. (They truly are a sight to see, and make for an incredibly romantic date with your loved one.) This book just doesn’t need much explaining, as its history truly speaks for itself.

Jeremy Anderberg, Book Riot

When Francesca enters that first covered bridge, the scene takes on the quality of a portal fantasy. In the oldest stories, people go deep into their own subconscious when they enter a cave. These covered bridges are a little unusual, and function symbolically as an amalgam of bridge plus cave.

Romantic Plots and the Erotics of Abstinence

(For a definition of ‘erotic’, see the short essay by Audre Lorde.)

Robert James Waller didn’t come up with the plot of this story from scratch. The Bridges of Madison County is said to be based on a 1934 play by Noel Coward called Still Life. Funnily enough, Noel Coward is another creator who got roasted for being a jack of all trades, master of none. (Shakespeare didn’t come up with his plots, either. His plays were based on popular, well-known stories of the era.)

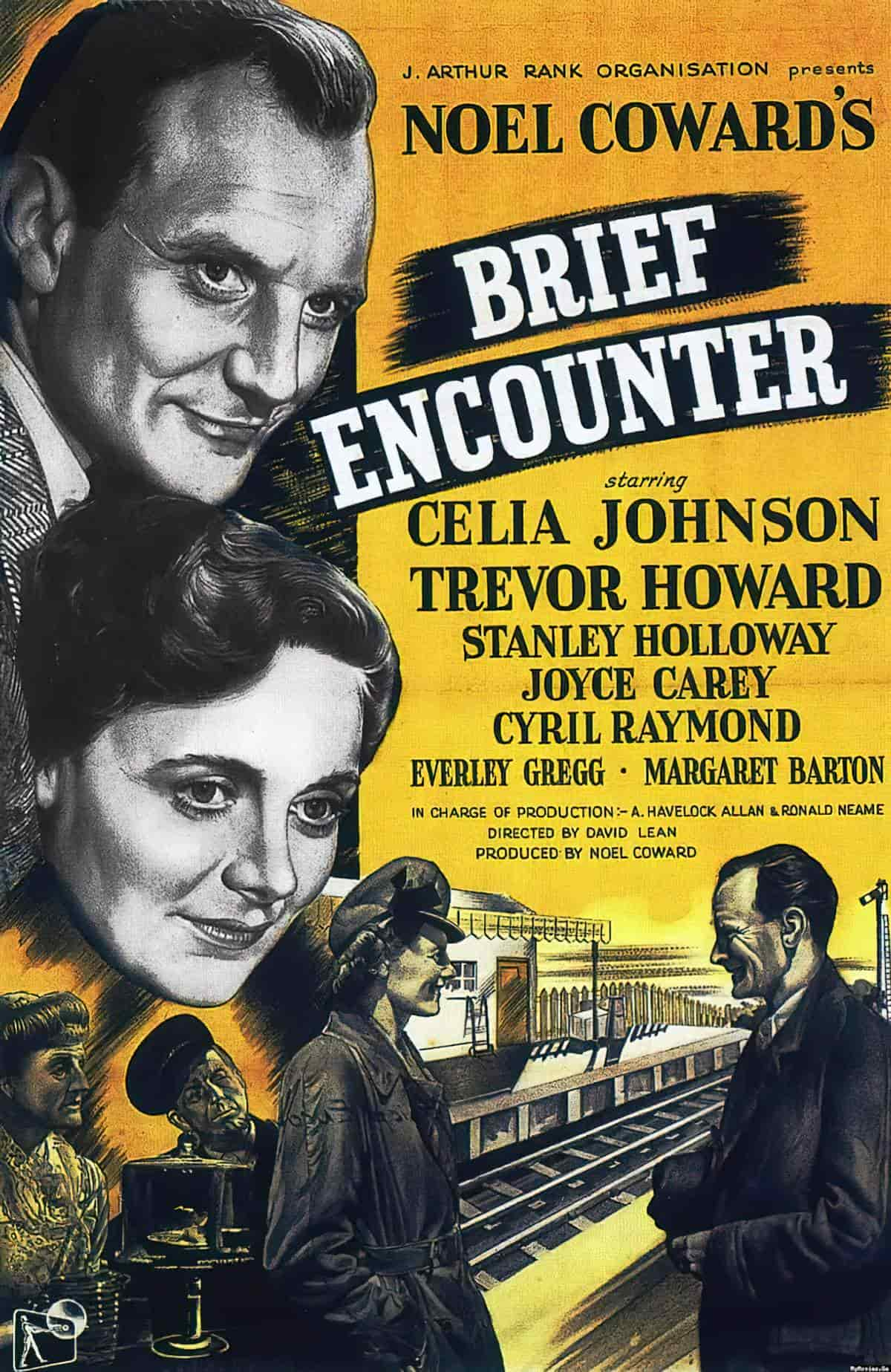

The Bridges of Madison County isn’t all that closely based on Still Life, which became the 1945 film Brief Encounter. (Note that any story with this plot might be called Brief Encounter.)

Here’s what all these stories share in common, alongside many others:

- Two romantic leads meet. Until very recently, this was always a cishet man and a woman. These people are ordinary people living ordinary lives according to societal expectations. One or both is already married to someone else, preventing this couple from proceeding into an uncomplicated love affair.

- Woman initially rebuffs the man. But the man shows himself to be caring and almost sage-like. He makes a few comments about life and love in general, broadening the woman’s mind. She’s never met a man so affirming before. He’s not the slightly bit needy, either, because he’s basically a rolling stone.

- The woman returns to her ordinary life. More time passes. The pair have been thinking about each other this whole time, fantasising.

- They meet again. There’s sexual tension and mildly combative flirtation. Little is said but much is implied.

- They talk to each other about how there’s no way they could possibly be together. There are too many other people to think about.

- They admit they’re in love. Without upsetting anyone’s marriage, they continue to meet in secret.

- Agonised by guilt, one party puts an end to the affair.

- Both parties yearn for a passionate farewell, but something intervenes to prevent this. Someone else is there — a talkative friend, a spouse. The pair never get their proper farewell, and never say goodbye. They remain important to one another for the rest of their lives, rarely meeting but figuring large in the imagination.

Annie Proulx also made use of this plot when writing “Brokeback Mountain“. I somehow doubt she’d appreciate the comparison. Proulx’s is not a romance but a story of hate, specifically of smalltown homophobia. (Apparently she has always refused to watch the film adaptation. It’s not a love story, dammit.)

What’s with the popularity of these stories? Partly they work by appealing to the erotics of abstinence. Nicholas Sparks has made a career out of this particular pain, but even Pride and Prejudice milks it right until the marriage between Lizzie and Darcy at the end. There is pleasure in abstinence.

This is how pleasure works: The things we crave the most are the things we can only have sometimes. It doesn’t just apply to lovers, it applies to everything. It’s part of educational theory. It’s psychology 101. You can’t have any chocolate. Now you want chocolate.

How Has The Story Aged?

Although the bulk of this story is set in 1965, when a new age hippie brings his sexually liberated ideas to a more conservative part of America, the story was of course written with 1990s sensibilities.

By the early 1990s, divorce still carried shame but an extramarital affair was no longer enough to ostracise a woman from her township forever. Hence the need for a 1960s flashback.

There’s one thing that really bothers me about The Bridges of Madison County though. It accidentally undermines its own feminist and sexually liberated message.

First the good part: 1990s audiences were encouraged to look more kindly upon married people, especially women, who fell in love (or in lust) with people outside the institution of marriage. This was a pretty radical idea of the time, and is ultimately a helpful and kind one.

But in order to show that Francesca is wonderfully human, and that to love is wonderfully human, the story relies upon a Madonna/Wh*re dichotomy to make its larger point. An interaction between Michael and Carolyn on the veranda goes like this:

MICHAEL: I found out who Lucy Delaney is. Remember the Delaney from Hillcrest Road?

CAROLYN: Yeah. But I thought she died.

MICHAEL: He remarried. Apparently they were having an affair for years. Apparently the first Mrs. Delaney was a bit of a stiff.

CAROLYN: You mean, she didn’t like sex?

MICHAEL: (nods, then simply): I bet Mom could’ve helped her.

CAROLYN: Boy. All these years I’ve resented not living the wild life in some place like Paris and all the time I could’ve moved back to Iowa.

The character of Michael, a.k.a. the writers, might have equally used the word ‘frigid’ instead of ‘stiff’ to mean the same thing, but of course they didn’t use that word, because by the 1990s, it was no longer okay to talk about women in that way. Yet ‘stiff’ means the exact same thing. It inherits the same meaning around deadness and coldness — the opposite of what a woman is required to be. This word reminds audiences that a (married) woman who doesn’t like sex is no use at all. It does not challenge this idea; it promotes it.

Misogyny will typically differentiate between good women and bad ones, and punishes the latter.

Kate Manne, Down Girl: The Logic of Misogyny

The storytelling reason for this scene: To show that despite her human weakness, Francesca was a beautifully sexual being, and someone we should all aspire to be. In order to show this, the storytellers decided audiences need a foil. In writing terms, the foil is the character held up as a moral counter example to the main character. Here, Francesca’s foil character is the first Mrs Delaney.

No one wants to be the desexualised first Mrs Delaney, right? No one at all… Wait a second.

When this story was written, in the early 1990s, the LGBTQIA+ community was smack bang in the middle of a massive struggle to be taken seriously by the straights. This struggle included the fight to have queer sex lives taken seriously.

What that activism didn’t include: Representation of the full spectrum of gender and sexual minorities. Activism of this era had excluded the asexual community entirely. In fact the word ‘asexual’ did not yet apply to humans, and even when this changed in the early 2000s, it took another ten years or so for the word to refer specifically to orientation. Vast swathes of the population still have no clue about any of these words.

In this same milieu, Alan Ball created Six Feet Under at the turn of the millennia. In many ways Six Feet Under was revolutionary in its representation of LBGTQ characters as fleshed-out individuals. Six Feet Under may have even been the first popular TV series to explore the different forms of attraction (sexual, romantic, aesthetic etc.) by showing Claire aesthetically but not erotically attracted to Edie. (It wasn’t called ‘split attraction’ back then. It required an ace community to give that particular cognitive dissonance a much-needed name.)

For all its good work, Six Feet Under made a hash job of aspec representation. On-the-page asexual Arthur is an allosexual’s warped idea of an asexual person. The nuzzling scene between Arthur and Ruth is infantalising and othering. Worse, there are several occasions when Keith (ultimately a sympathetic character) derides Arthur as an example of how not to live a life. Asexual Arthur doesn’t get his own character arc. He disappears in embarrasment under a cloud of disgrace. At best we feel sorry for him as he skulks away.

Back to Bridges of Madison County. “The first Mrs Delaney” gets only one mention, and we know nothing of her backstory. Why didn’t she ‘like sex’ (according to smalltown gossip)? That could have been for many reasons. Perhaps she was sex-averse and asexual. Perhaps she didn’t like sex with her husband in particular. The viewer fleshes out the single mention. This one mention happens in a significant scene. The scene is significant to the plot because it shows the audience how Francesca’s adult children have changed. They now see their own mother as a fully rounded sexual being.

This snippet of dialogue sends any audience a clear message: There is really only one proper way to live a life, and that is to be a sexual person.

Six Feet Under used Arthur to the same end. Perhaps you can think of other examples of ‘stiffs’ used as foils for sympathetic allos, propping up a dominant culture of compulsory sexuality. There is a particularly damaging House episode, notorious in the ace community. I won’t link to it.

Storytellers don’t actually need to throw aspec communities under the bus when conveying the (now widely-accepted) idea that, for allos, to have a good sex life is necessary and healthy and should carry no shame. But storytellers do still throw other sexual minorities under the bus when telling these stories.

It’s not just sexual minorities thrown under the bus, of course. That Madonna/Whore dichotomy is never any good for women, and that’s what this also is. (Notice how anything which throws queer people on the bus gets its kickstart from misogyny. Anything.)

The comment in The Bridges of Madison County about the poor, ‘stiff’ Mrs Delaney undermines the on-the-surface feminist message of The Bridges of Madison County, the one which shows how even married mothers are sexual beings.

When a ‘stiff’ woman is used as a foil, this sends another equally clear message: A sexually non-performing (possibly asexual) woman is no use to her husband, and women always owe their husbands their bodies.

[A] woman is regarded as owing her human capacities to particular people, often men or his children within heterosexual relationships that also uphold white supremacy, and who are in turn deemed entitled to her services. This might be envisaged as the de facto legacy of coverture law—a woman’s being “spoken for” by her father, and afterward her husband, then son-in-law, and so on. And it is plausibly part of what makes women more broadly somebody’s mother, sister, daughter, grandmother: always somebody’s someone, and seldom her own person. But this is not because she’s not held to be a person at all, but rather because her personhood is held to be owed to others, in the form of service labor, love, and loyalty.”

Kate Manne, Down Girl: The Logic of Misogyny

Disgust functions as validation for disposability, producing aging bodies as disgusting and banning them from sex […]. Notably, the attribution of non-sexiness is especially harmful to women, who are commonly habituated to assessing their value in terms of youth, beauty and sexiness. The effect of this is the process by which, through a devaluing of their appearance — that is, the loss of their sexiness — a ban against sexual enjoyment is implemented, since ‘if elderly women can’t be beautiful, they obviously can’t have sex, either’ … . Also, cisgender women are understood to be disposable in a particular way after they cease to be reproductively useful and capable of precreation. If disgust is a visceral response that points to a desire to maintain bodily boundaries and one’s psychic sense of self, then a disgust based response to ageing keeps the segregation of the young and ageing in place, facilitating the enactment of compulsory sexuality for the young and young-approximating, and the desexualisation of the elderly.

Ela Przybylo, “Ageing asexually: exploring desexualisation and ageing intimacies in Sex and Diversity In Later Life, 2021.

The Bridges of Madison County succeeds as a criticism of the desexualisation of older women. In the 1960s (clear to a 1990s audience) ‘older women’ meant a housewife in her mid-40s. But this story fails in its criticism of compulsory sexuality. In fact, the story actively promotes it.

It is possible for a story to be critical of desexualisation and also critical of compulsory sexuality. But we need to look to more enlightened writers than Robert James Waller.

When Annie Proulx subverted this romance plot for “Brokeback Mountain” she avoided throwing other gender and sexual minorities under the bus.

So too did Alice Munro when she wrote her short story exploring the nuances of infidelity, “Fiction“.

More generally for writers, when setting up character webs, be careful who you choose to use as your foils.