What does dinner time look like in your house? Do you see your own family tradition reflected in children’s books?

I remember hearing once — perhaps on the yak track of Downton Abbey — that, for film makers, table scenes are the most difficult to shoot and edit. Unlike in any other scene, the characters sit close together, side-by-side, talking in what’s basically a huddle. More than that, camerawork has to create the illusion that characters are speaking to the right characters, so they have to be looking in the right direction.

Fans of the TV series “Downton Abbey” are excitedly awaiting the premiere of the movie on Friday of this week. And coinciding with the movie’s release is the publication of “The Official Downton Abbey Cookbook,” by Annie Gray, one of Britain’s leading food historians who joins Linda on today’s episode. Dr. Gray researched recipes from historical sources for the meals seen on the show and includes notes on the ingredients and customs of the time. She gives a warm and fascinating insight into the background of the dishes that were popular between 1912 and 1926, when Downton Abbey is set – a period of tremendous change and conflict, as well as culinary development, which makes the book a truly useful work of culinary history.

Dining at Downton Abbey

Illustrators of static table scenes have it a bit easier — there’s no need to fit a massive camera into tight spaces, for one thing. But illustrators still have the problem of staging. And tables say so much.

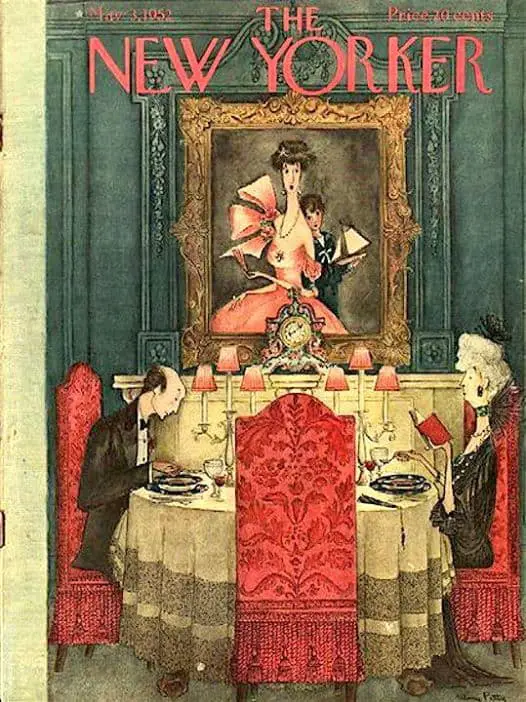

The long table, with one character at each end, is often used to depict a cold, stand-offish, antogonistic character web. You can see this in films such as American Beauty. Fighting parents at one end, child stuck in the middle as reluctant piggy-in-the-middle. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hO66DoF7fGc

In the classic painting below, the table separates two characters. The blue tones suggest coldness between them. All of this is emphasised with the positioning of the vase, which creates a visual barrier.

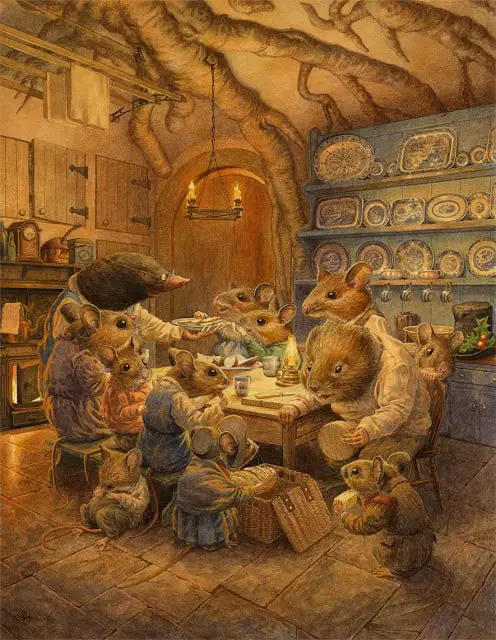

In picture books, with their bustling, happier atmospheres, illustrators want to avoid anything like the asparagus scene of American Beauty.

Joyce Lankester Brisley’s hygge, happy scenes also feature a long table with Mother at one end, Father at the other, but there’s no coldness whatsoever. There’s the expanded cast, for one thing, but there’s also Milly Molly Mandy in action, about to get out of her chair, and the pets in the foreground, also looked after. The house itself is cosy, with its patterned curtains and view to the hint of nature outside.

FICTIONAL FAMILIES WHO DON’T EAT AT THE TABLE

This is still rare, from my own observations. In broader pop culture, the fictional family who eats with the TV on, or in front of the TV, is portrayed in that way because they are dysfunctional. Picture books teach a clear lesson: Good families eat together, sitting on Western chairs, at a Western table.

- Mog’s family sits at the table, though Judith Kerr wrote those in an era where more families did sit at the table. In fact, the formality of eating came in handy for Kerr when writing The Tiger Who Came To Tea, in which a carnivalesque visitor upturns social conventions. The more formal that convention, the more fun it is to subvert it. Admittedly, this is part of the reason why table dinners are so popular with picture book creators.

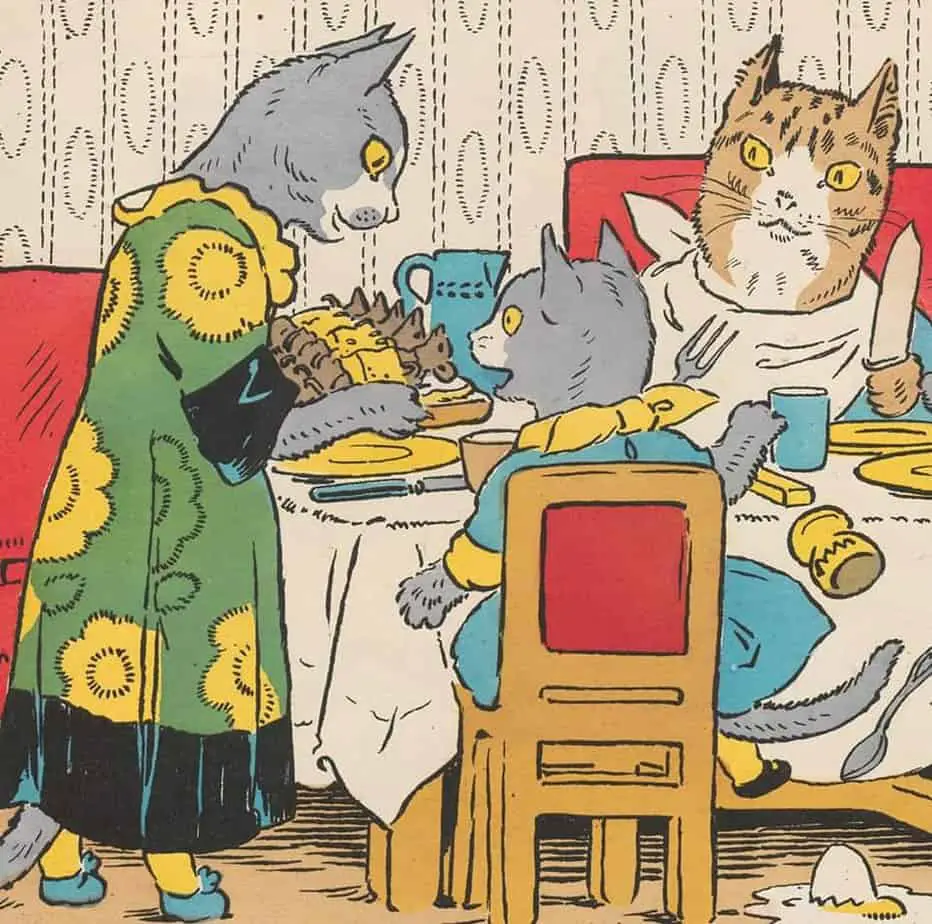

- Another reason animals might sit around a table: To make them more human. This explains why Olivia the Pig has to sit at a table. Olivia the Pig sits at a round table, which admittedly is less formal than a long, rectangle.

PHOTOGRAPHS OF FAMILIES EATING DINNER

This photo series shows how many cultures around the world sit on the floor to eat dinner. This could be reflected in picture books, but largely is not.

Here’s a photo series of Americans eating dinner — a significant proportion are in the sitting room rather than at a table, though does skew towards table when people eat as a family rather than as a couple or alone. (Kids are messy, which is one good reason to eat in the kitchen, or on a hard floor.)

And here’s a series of British people eating dinner, which includes a tea trolley. I did actually see that in use when I worked at a high school in England. Each morning the principal ordered breakfast which was delivered to him on a trolley. Coming from New Zealand, this struck me as foreign.

In Australia, Annabel Crabb made a series about the history of Australian life, with emphasis on food. The images look more staged than you’d want in a typical picture book, but a lot of thought has gone into the colour palette, which can be inspiring for illustrators. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MjXaqAsoviY&feature=youtu.be

What The World Eats is a photo series in the same vein, and sobering. I doubt I could personally survive on some of those weekly rations.

DADS COOKING IN PICTURE BOOKS

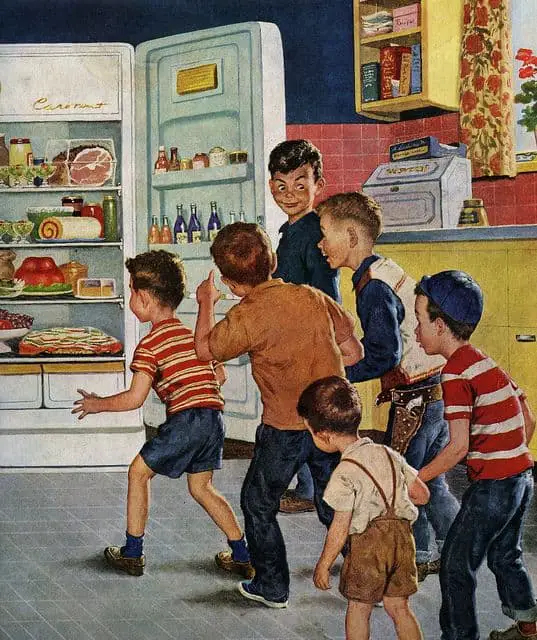

There is a tendency across all fiction to idealise the 1950s and 1960s middle class of America, in which mothers stayed in the home, happily raising the children and preparing elaborate meals. There remains a tendency in picture books to replicate that hygge imagery.

Here’s what we need to see more of in picture books:

- Dads doing the cooking

- Dads actively involved in helping children eat their food (rather than, say, reading the newspaper)

- Happy, active families who aren’t necessarily eating dinner at the dinner table. There’s nothing especially magical about the dinner table. Families can eat happily outside around a BBQ, on the floor, and even as they watch TV together, especially if they’re talking about it as they eat.

RELATED AND INTERESTING

SNACKS HAVEN’T ALWAYS BEEN A THING