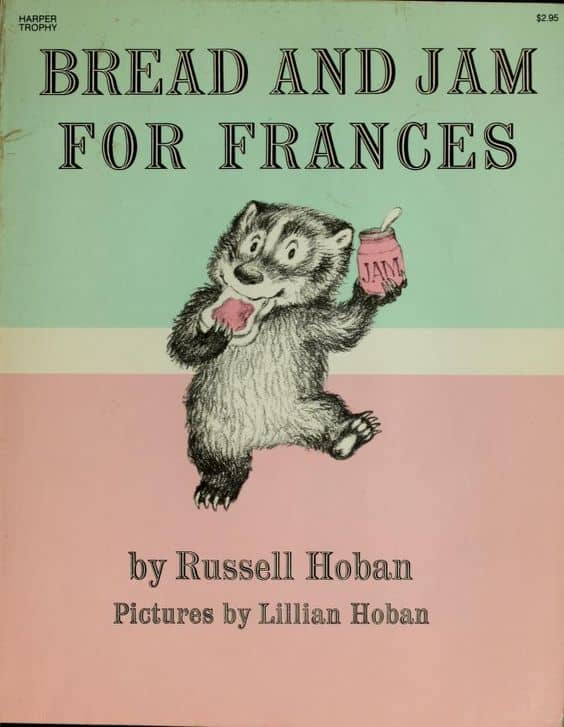

Bread and Jam for Frances is a picture book written by Russell Hoban, illustrated by Lillian Hoban, first published in 1964 as a part of a series about a girl in the body of a badger, who lives in a middle class house and has access to all the spoils you’d expect of 1960s middle class Westerner.

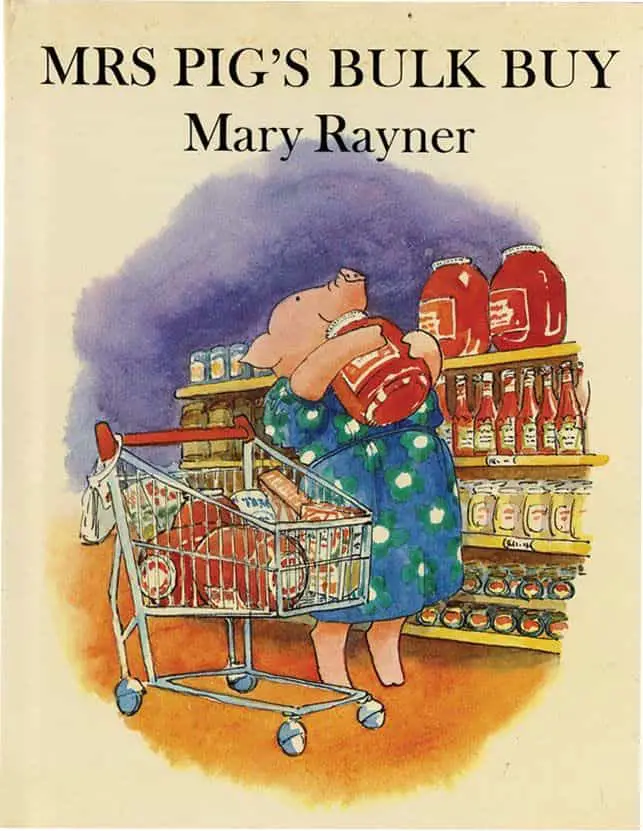

I never came across this picture book as a kid, but a book with a similar plot must have really affected me because it was probably read once in class, yet I remember it profoundly: The book I’m talking about is Mrs. Pig’s Bulk Buy, one of the Pig Family picture books by Mary Rayner. This family of pigs might be considered the 1980s follow-up to the Hobans’ Frances stories. (I’ve taken a close look at Garth Pig and the Ice-cream Lady on this blog.)

In Rayner’s 1981 version of Bread and Jam for Frances, the mother pig of the Pig Family gets utterly sick and tired of her piglets hoeing into the tomato sauce so she feeds them nothing but tomato sauce until they crave a more varied diet.

No matter how carefully she flavored the stews or spiced the puddings, the piglets always squealed for tomato ketchup. She had always tried to stop them from having it, and make one bottle last a week, but it was always gobbled up by Monday and then the piglets would grumble until she went to the supermarket again.

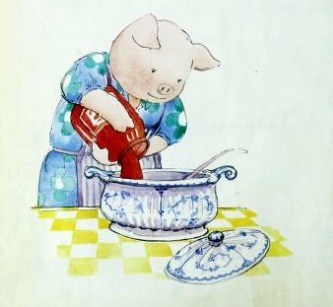

“But things will be different soon,” thought Mother Pig happily. She reached down one of the big jars and emptied it into a huge soup tureen.

My mother was frequently complaining about the family using too much tomato sauce as well, which is probably why the story stuck with me. (Criticism was mostly directed at our father, though, who used sauce not only for flavour, but to cool hot food to a more scoffable temperature.)

DIDACTICISM AND FOOD PREFERENCES

Do these stories do what they intend, that is, to encourage children to eat a more wide and varied diet? One Goodreads reviewer of Rayner’s picture book said, “I read this to my daughter in the hopes of encouraging her to eat less ketchup, but all it did was make her want ketchup sandwiches.”

I doubt these stories work as intended. I do remember Rayner’s story, but I don’t remember going easy on the tomato sauce. They appeal to adults for didactic reasons, and to children for the carnivalesque element. Eating nothing but your favourite food is peak carnivalesque fun. The ending of both stories doesn’t resonate; doesn’t count.

Parenting culture has changed since the 1980s and certainly since the 1960s. For better or for worse, modern parents hand more food choice over to their children. I know plenty of kids who’d be quite happy to eat nothing but white bread and jam for weeks on end, possibly forever. Some of them have sensory issues around eating, which is the first thing I thought about Frances as she described and personified her eggs.

STORY STRUCTURE OF BREAD AND JAM FOR FRANCES

PARATEXT

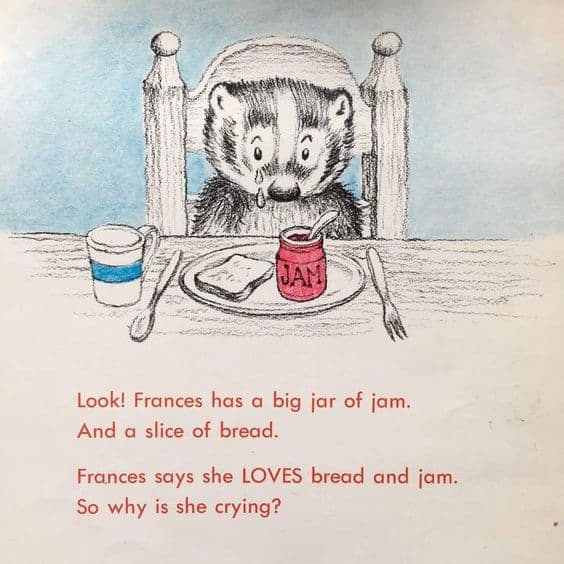

Frances is a fussy eater. In fact, the only thing she likes is bread and jam. So she’s delighted when Mother and Father grant her wish and give her bread and jam at every meal. This endearing story of how Frances faces unlimited bread and jam is a classic that will continue to be gobbled up by children, picky eaters, and parents everywhere.

marketing copy

Frances is also described as ‘America’s favourite badger’. (Frances is about as badger as Olivia is pig.)

SHORTCOMING

Frances has food preferences (possibly for sensory reasons) but she is a member of a family who have no tolerance for people who don’t eat what’s going.

DESIRE

Frances wants to eat bread and jam instead of eggs.

OPPONENT

Mother.

Is the school mate a plan or an ally. I find him insufferable. “Well, goodo for you,” I wanted to tell him, and, “I don’t remember asking for all those details about your damn lunch.”

PLAN

The mother has a secret plan, and we see it play out. The mother is basically a trickster, and I guess this is why she appeals to many mother co-readers; trickster mums are rare in children’s books.

THE BIG STRUGGLE

Frances grows more and more tired of bread and jam. When the mother serves Frances the same dinner as the rest of the family is having, Frances is so keen for something different that she eats it up without complaining. Mother has won this battle.

ANAGNORISIS

Frances realises that a varied diet is an interesting diet.

NEW SITUATION

Frances is eating a varied school lunch.

EXTRAPOLATED ENDING

We extrapolate that Frances is permanently fixed and that she’ll never look at bread and jam in the same way again.

RESONANCE

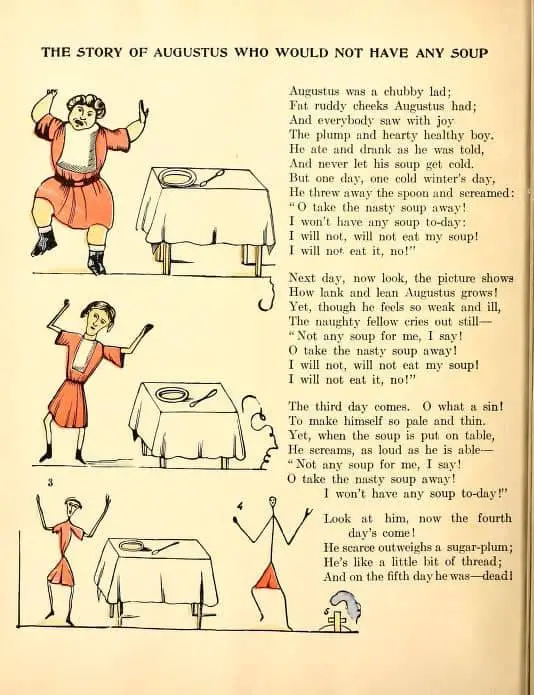

I was prompted to read Bread and Jam for Frances after seeing the following image memed around the Internet. It’s actually an abbreviated version of the relevant page, and almost functions as a tagline. In abbreviated form, without any context, this image is perfectly suited to modern meme culture. Perhaps it encapsulates our collective existential loneliness.

FURTHER READING

- The Evolution of Breakfasts in Fiction. In the 1960s, America was in the middle of switching over from cooked breakfasts to breads and extruded cereals. Frances in this story has clearly been influenced by the modern Continental breakfast (probably from ads on the TV) but her old-school mother resists.

- Egg Symbolism. I wonder how many humans across history have found eggs disgusting. Until battery farming, eggs were a hard won delicacy and an important element of many diets.

- The idea that all of the other kids will get something, and that you, due to your own moral shortcoming will miss out, was utilised by Beatrix Potter in Peter Rabbit, and in many stories after that, including Little Golden Books’ super popular The Poky Little Puppy. But can you think of any modern picture books which use this kind of punishment plot, withholding food from children? This was certainly how I was brought up. But I suspect it’s had its day.

- Russell and Lillian were married Americans who moved to England together in 1969. However, Lillian moved back to America about a year later. Russell stayed in England and married someone else in the mid 1970s. They each continued to have a full and varied career in children’s books, independently. Russell died in 2011. Lillian died in 1998.

- See also my collected notes on The Mouse and His Child.