**UPDATE LATE 2024**

After Alice Munro died, we learned about the real ‘open secrets’ (not so open to those of us not in the loop) which dominated the author’s life. We must now find a way to live with the reality that Munro’s work reads very differently after knowing certain decisions she made when faced with a moral dilemma.

For more information:

My stepfather sexually abused me when I was a child. My mother, Alice Munro, chose to stay with him from the Toronto Star

Before Alice Munro’s husband sexually abused his stepdaughter, he targeted another 9-year-old girl. ‘It was a textbook case of grooming’ from the Toronto Star

So, now what?

Various authors on CBC talk about what to do with the work of Alice Munro

And here is a brilliant, nuanced article by author Brandon Taylor at his Substack: what i’m doing about alice munro: why i hate art monster discourse

“Boys and Girls” is a short story by Alice Munro, first published in a 1968 edition of The Montrealer. Find it also in Dance of the Happy Shades (1968), Munro’s first collection. As the title might suggest, this story in the collection is Alice Munro investigating gender roles, and how we are all acculturated into two binary groups, boys and girls.

You can read Boys and Girls online here, though I suggest reformatting, or narrowing your browser window for comfortable viewing.

It’s likely many younger readers have never encountered a real fox fur, or any fur, for that matter. My grandmother’s second husband—originally a butcher by trade —gifted her a stole made of fox. They married in the late 1970s, when fur stoles were already on the wane and I doubt my fashion-savvy nana ever wore it. Instead she used it to decorate one of her spare beds. She must have seen the life in it, because she arranged this fox to look as if it were sleeping. (She may have immediately gotten rid of it had she not minded offending her husband.) Whenever I stayed the night at Nana’s house, I was required to sleep in the fox bed, and this meant disturbing the sleeping fox before wedging myself between the very tightly-tucked sheets. The eyes were the creepiest thing; not eyes, but holes.

I add this memory to the horror of walking into the shed at the bottom of the neighbours’ yard. I was friendly with the little girls next door. Their father was rarely present, a formidable man who despised children. He was mostly away, hunting in the forest. He hunted brushtail possums, a pest in New Zealand, though protected in their native Australia. The shed at the back of their house was filled with hundreds of possum pelts hanging from the ceiling. Again, it wasn’t the fur that horrified, but holes where eyes should have been.

“BOYS AND GIRLS” IN A NUTSHELL

SETTING

As a girl, the narrator grows up on a fox farm outside Jubilee (a fictional town explored later in The Lives of Girls and Women). She and her brother Laird watch their father skin foxes in the basement. Their lives are filled with workaday horrors of early 20th century farm life, reminiscent of a medieval town, with its surrounding fence to keep the foxes in, and its ‘streets’ of pens. The pens are where fox bodies are confined and controlled, looked after because they will provide the pelts and the next generation of pelts.

As you read, notice how the farmhouse, which contains the mother, is similar to the fox pens. There’s some mise en abyme going on here—the entire farm is surrounded by a fence, which contains a farm house, and nearby smaller, animal versions of the farm house.

When the father works inside the house, he does his fox skinning in a white-washed basement. Watching from the steps, the children observe the skinned foxes are smaller than expected. Probably like human babies. The white-washing suggests something macabre, but also something sanitised, hospital-like.

IMAGINARY PARALLEL LIVES

Alongside the day-to-day reality, this girl lives in a parallel imaginary world in which she gets to play the role of hero. Her father is also a literary person. His favourite story is Robinson Crusoe, and he displays Robinsonnade creativity when setting up the neat and tidy fox farm. So we can see early in the story, narrative is important to these characters. Fiction is as formative as reality.

Daniel Defoe relates the tale of an English sailor marooned on a desert island for nearly three decades. An ordinary man struggling to survive in extraordinary circumstances, Robinson Crusoe wrestles with fate and the nature of God.

Later, her stories will change. She will start to self-objectify, and think about how she looks to others, what kind of dress she’s wearing. This will show readers how she has fully internalised her feminine role.

(Alice Munro keeps coming back to this theme, notably in “Spaceships Have Landed”. Two girls grow into young women. They lose friendship with each other, and also their ability to switch genders in their childhood games. They lose their freedom alongside their genderflux games.)

GENDERED ROLES

The girl narrator absorbs various gender messages from the culture around her:

- Women’s work isn’t as valuable as outside farm work

- Nor is it as interesting

- Boys and men are more useful because they are stronger

- No matter how conscientiously a girl works, she’ll never be considered as valuable on the farm as a boy.

BOLTING HORSE AS METAPHOR FOR TEMPORARY FREEDOM

Although this is a fox farm, the main animal characters are horses.

One day, the narrator takes her younger brother to the barn where they can peer through a knothole and observe a horse being shot. This disturbs them a little but they are grimly fascinated. The girl thinks she might get in trouble if her little brother tells, so she takes him with her to see a show that evening, and hunts out a cat about to give birth. He doesn’t tell.

MEN AS DEATH; WOMEN AS BIRTH

When the girl takes her brother to look for a mother giving birth, we can see that men are associated with death (hence skinnings in the basement, and horse shootings behind the barn), whereas women and girls are associated with birth. In our need to keep these two things separate (though they are part of the same cycle), it is a psychological trick to keep them separate by gender.

Munro also links the father to death by giving us an image of the father with a scythe, reminiscent of the Grim Reaper.

FLORA AS SYMBOL OF FEMININITY

But next, it’s time for another horse to be shot, one the children didn’t expect would be shot. The horse’s name is Flora. Flora, flowers; the horse is gendered. It’s there in the name, because women are associated with beauty and pretty things and regeneration, as are flowers.

Unlike the other, male horse, who remained stupidly oblivious, Flora the horse seems to know what’s about to happen to her. She bolts. This parallels the way in which the girl narrator gives great thought to her gendered fate, whereas her younger brother need not wonder about any of that. He doesn’t have to wonder about gender roles because his fate lines up with his desires, insofar as his desires have been allowed to go.

the family as a site of feminine care serves capitalism by giving men emotional and sexual compensation for the coercion of market relations. The hidden cost of this is the coercion of the hidden patriarchal home: a cost borne principally by women.

The Right to Sex by Amia Srinivasan (2021) p120

The girl narrator has the opportunity to shut the gate to prevent Flora the horse from running away but she doesn’t.

Even when a horse bolts out into the world, the entire world may as well contain a fence. To the young girl narrator, the whole world is gendered.

Instead, the men (plus her little brother) go after the horse as the girl narrator retreats to the house, sad and shaken.

The ‘men’ come back for dinner having caught Flora, shot her and cut her up for meat. The younger brother describes this to the women. It is clear he has no empathy for the horse as a being. The horse is simply an animal to him. He is completely divorced from her.

This time, the younger brother tells on his big sister for failing to shut the gate. Expecting to get into trouble, the narrator is surprised when her father says simply, “She’s only a girl”.

The girl narrator thinks maybe her father is right. The internalisation of gender roles is complete.

THEME: THE SOCIALLY IMPOSED RESTRICTIONS OF IMPENDING WOMANHOOD

“Girls don’t slam doors like that.” “Girls keep their knees together when they sit down.” And worse still, when I asked some questions, “That’s none of girls’ business.” I continued to slam the doors and sit as awkwardly as possible, thinking that by such measures I kept myself free.

“Boys and Girls”

The narrator of “Boys and Girls” echoes Simone de Beauvoir, who famously said that one is not born a woman, but becomes one.

One is not born, but rather becomes, a woman. No biological, psychological, or economic fate determines the figure that the human female presents in society; it is civilization as a whole that produces this creature, intermediate between male and eunuch, which is described as feminine.

The Second Sex, opening line of Book II, Chapter 1: Childhood, Simone de Beauvoir (1949, 1953)

A girl was not, as I had supposed, simply what I was; it was what I had to become.

“Boys and Girls” by Alice Munro

Here’s the wider context in Munro’s short story:

The word girl had formerly seemed to me innocent and unburdened, like the word child; now it appeared that it was no such thing. A girl was not, as I had supposed, simply what I was; it was what I had to become. It was a definition, always touched with emphasis, with reproach and disappointment. Also it was a joke on me.

“Boys and Girls” by Alice Munro

A CHARACTER NAMED FLORA

Three short stories by Alice Munro feature a character named Flora: “Boys and Girls,” “Friend of My Youth,” and “Runaway.” Written over a period of almost forty years, they reveal the interactions between animals and humans, the power of sexual myths, the violence of patriarchal hierarchies and Munro’s metafictional strategies that open the door wide to interpretation.

Alice Munro Opens Wide the Gate for her Three Floras, Walter Hesford

In this story, Flora is a horse. But the horse is the spirit animal of the girl narrator.

In stories, the death of an animal almost always prefigures some kind of death or spiritual death of a character. The death in this short story: The end of childhood. ‘Girl’ is taking on a new meaning, one which will prepare the young narrator for womanhood, in which she’ll be required to go inside the house and help her mother. Her free life outdoors will come to an end.

Alice Munro leaves readers to make this connection. As a child, the girl doesn’t know why she leaves the gate open for Flora to have a go at running away, but as an adult, the narrator must have made the connection, hence the reason for these particular events in the story.

PELTING AS METAPHOR

Munro effortlessly uses metaphors of place and event to reveal deep interior turbulence and ambivalences: e.g. the ‘pelting’ of the beautiful foxes in the ‘Boys and Girls’ becomes wonderful resonance for the way in which the narrator is skinned by the process of growing in to the skin of a ‘girl’—and must go through the act of un-skinning herself to find her sneaky, savage and hostile self that will fight this reduction.

The London Literary Salon

Alice Munro has made oblique use of fairytale allusions in other stories in Dance of the Happy Shades (e.g. “The Little Mermaid” in “An Ounce of Cure“, “Bluebeard” in “Sunday Afternoon“, “The Red Shoes” in “The Time of Death“). Not having studied these stories in order, I’m primed to find another fairy tale allusion in “Boys and Girls”.

Perhaps “Donkey Skin”?

FAIRY TALE ALLUSION

There’s an entire family of fairy tales (Aarne-Thompson type 510B) in which have in common beautiful dresses, parties, and a what folklorists call a ‘recognition token’—how true lovers recognise each other e.g. the glass slipper of Cinderella.

A common part of the plot: The girl wears the skin of an animal. She is revealed to be a worthy girl (a princess) while bathing. Yes, this is all very creepy. Importantly, donkey skin tales are about the transformation from girlhood to womanhood, as werewolf stories are also about puberty.

When I read the Donkey Skin tale as transcribed by Perrault, it struck me how much happier the girl would have been had she stayed in the woods, wearing her donkey skin. Instead she was passed from man (father) to man (prince) to man (father-in-law), each one desperate to own a piece of her feminine sexuality.

Same can be said of Alice Munro’s narrator in “Boys and Girls”.

If you’d like to hear “Donkeyskin” read aloud, I recommend the retellings by Parcast’s Tales podcast series. (They have now moved over to Spotify.) These are ancient tales retold using contemporary English, complete with music and Foley effects. Some of these old tales are pretty hard to read, but the Tales podcast presents them in an easily digestible way. “Donkey Skin” was published Feb 2020.

Note that the Donkeyskin fairytale is never named on the page. This is one example of many, many folk- and fairy tales in which the girl is the object, the male character the subject. The explicit allusion is Robinson Crusoe, which the father has internalised. Unlike the princess of the fairy tales, Robinson Crusoe has full agency and dominion over ‘his’ realm. (The story is of course an example of cosy colonialism.)

THE IMPORTANCE OF NAMING

Numerous times across this story, Alice Munro mentions how animals are named. We never learn the narrator’s name, because this girl could be any girl. She is the Every Girl. Every girl of the era is expected to ditch her childlike boyishness whether she wants to or not, whether she lives on a farm or in the towns.

The foxes get names if they prove themselves good for breeding. In light of the feminist messages, this feels significant.

When the horses come to live briefly with the narrator’s family before they are shot and used for meat, they are given temporary names, regardless of whatever they happened to be called before. Their names change along with their use: from workhorse to meat horse.

Today, rather than ‘names’, we frequently think in terms of ‘labels’. ‘Girl’ and ‘boy’ are also labels. This binary classification seals a child’s fate.

THE SAD TURN

Many touching and resilient characters in [Dance of the Happy Shades]. There’s also always a subtle sad turn—the nature-loving girl gradually losing her ambition resisting the world’s biased view on girls and “being girlish”, the female writer giving in to the societal expectation of being a stay at home mom [“The Office“], the peddler father struggling with his livelihood [“Walker Brothers Cowboy“], the thwarted adolescent love failing to bloom for the second time in adulthood…

a consumer review

The sad turn in “Boys and Girls” happens when the narrator lets the horse free but realises the horse will never be free. She will be caught and skinned and used for her meat. There’s no escaping her fate. On the farm, where secondary sex characteristics really do mean something (where manly strength is a requirement for outdoor manual labour), biology really is destiny.

RESONANCE

This short story concerns itself with how a girl learns to be a girl-and how awkward that learning is. The story was written fifty years ago and is set in a time before then—but still; there is something recognizable about the way we are socialized to a reduced form of ourselves (boys AND girls) to ‘right’ ways of behaviour and an acceptance of inequities that stated openly, I would not accept.

The blog Laura Bates started to simply hear (is that the right verb for electronic admissions?) examples of everyday sexism has hit an unexpected nerve and revealed a level of daily sexism that is astounding. And here is the meet for me: as a deep believer in the power of relationships to bridge divides (gender, nationality, age, race, beliefs…) I can not believe how far we have not come. Or how short a distance we have gone in our ability to reduce gender oppression knowing as much as we do.

The London Literary Salon

FURTHER READING

In this episode of Talk Nerdy, Cara is joined by Dr. Lucinda Jackson, author of “Just a Girl: Growing Up Female and Ambitious.” They discuss her personal experiences navigating the pernicious institutional sexism of academia and corporate America, as well as its implications for broader society.

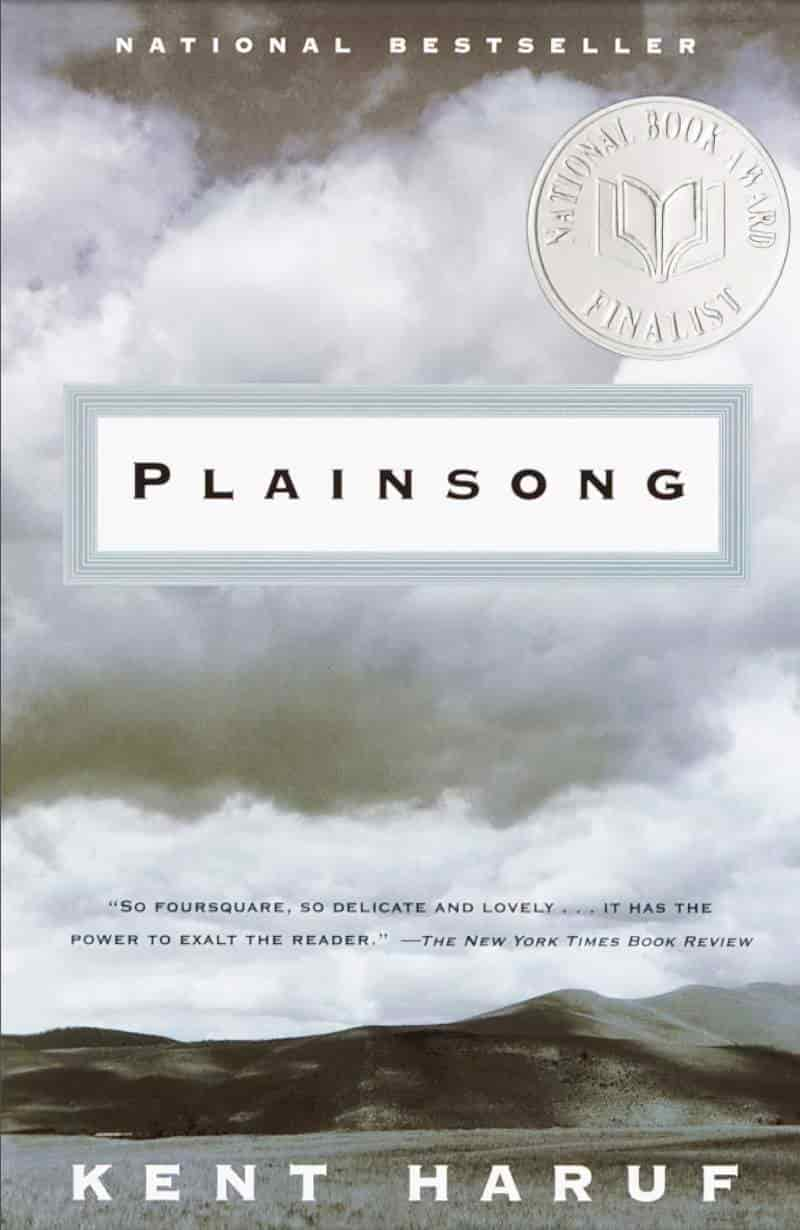

Reminiscent of ‘Plainsong’ [a novel by Kent Haruf], the story is told through the point of view of a young girl who prides herself on being her father’s helper, hating the life her mother has endures, chained as she is to domestic house-bound chores. The presentation of the girl’s character is complex. “In one sense, she is indignant at the way she is gradually frozen out of the masculine world, but at the same time Munro shows how she begins to grow, almost in spite of herself, into her mysterious role as a “girl”. We see her standing in front of the mirror, “wondering if I would be pretty when I grew up.” At the end of the story, she doesn’t even protest the way she is belittled as “only a girl”, commenting “maybe it was true.”

a consumer reviewer

PLAINSONG BY KENT HAUF (1999)

A heartstrong story of family and romance, tribulation and tenacity, set on the High Plains east of Denver.

In the small town of Holt, Colorado, a high school teacher is confronted with raising his two boys alone after their mother retreats first to the bedroom, then altogether. A teenage girl—her father long since disappeared, her mother unwilling to have her in the house—is pregnant, alone herself, with nowhere to go. And out in the country, two brothers, elderly bachelors, work the family homestead, the only world they’ve ever known. From these unsettled lives emerges a vision of life, and of the town and landscape that bind them together—their fates somehow overcoming the powerful circumstances of place and station, their confusion, curiosity, dignity and humor intact and resonant. As the milieu widens to embrace fully four generations, Kent Haruf displays an emotional and aesthetic authority to rival the past masters of a classic American tradition.

OTHER STORIES IN DANCE OF THE HAPPY SHADES (1968)

- “Walker Brothers Cowboy” — A woman looks back at her 1930s childhood. Her family has 2 or 3 months earlier lost the family fox farm and moved to a small town on the edge of Lake Huron, where the father has started a new job as a door-to-door salesman. Meanwhile, the mother sinks into a depressive state. One day, the father takes the narrator and her younger brother on a ride, where he visits an old friend/lover. The daughter learns that her father had another sort of life once.

- “The Shining Houses” — In a new neighbourhood, many houses have been built next to an old one. The owner of the older house, Mrs. Fullerton, does not take care of her property to the extent that the owners of the new houses would like. They conspire to get rid of the old poultry-farming witch. Only our narrator seems conflicted.

- “Images” — A little girl is the narrator of this double character study: A second cousin who came to take care of the household while her own mother was sick, and a man with a psychotic mental illness who lived alone in the woods. After meeting the man in the woods, the little girl learns not to be afraid of the woman who has infiltrated the household to take care of them all.

- “Thanks for the Ride” — This story is written with the viewpoint character of a young man. He has just finished school and is out with his older cousin with the purpose of losing his virginity. Together they pick up some ‘loose’ girls. The whole experience is perfunctory and defamiliarizing.

- “The Office” — A housewife decides to improve her life by carving out some time for herself to pursue her passion of writing. So she rents a room above a hair salon and drugstore. But the landlord won’t leave her in peace, deeming her time his.

- “An Ounce of Cure” — A young teenager is pining after a boy who dumped her months ago for another girl. She can barely think of anything else. One night she is babysitting when she spies three bottles of liquor on the bench. She accidentally gets very drunk and very caught out. Her reputation is ruined. But as an older woman looking back on this time, she is glad it happened.

- “The Time of Death” — A mother who lives in one of the squalid cottages on the edge of town has lost a child in a terrible accident. The village gathers round, but how genuine are they in their grief?

- “Day of the Butterfly” — Two girls at a primary school are ostracised. One is the narrator, now grown, ostracised for being an out-of-towner who doesn’t wear the right clothes. The other is more ostracised still, because her parents are immigrants, because she smells like rotting fruit, and because her brother needs her to accompany him to the toilet. When this girl is dying in hospital from child leukemia, the young narrator is filled with inexplicable grief. It is now too late to be a real friend to this outcast, and anything she does in kindness will feel empty and pointless.

- “Boys and Girls“

- “Postcard” — A woman around the age of 30 has been seeing a man for years. They’re long-term partners. The reason they haven’t married: He’s waiting for his mother to die. His mother wouldn’t approve of him marrying the narrator, we deduce because of the wealth disparity. Unfortunately for the narrator (Helen), turns out the guy never intended to marry her anyway. He sends her a postcard from Florida telling her how he’s having such a good time. Next minute, Helen’s best friend is round to break the bad news: It’s been published in the paper, the lover is getting married to someone else after all this time. The weasel didn’t have the gumption to let Helen know. So she goes round to his house, stands outside and expresses her grief in a very vocal way.

- “Red Dress—1946” — A thirteen-year-old girl’s first ball. Her mother sews a red dress with a princess neckline. Suddenly she looks much older. She barely recognises herself in the mirror, and longs for childhood again. Almost all the girls around her are obsessively interested in boys. Everyone, that is, except one other girl who says she despises boys, and plans to support herself by working as a P.E. teacher. But by aligning herself with this queer girl, our thirteen-year-old risks much. What will she do? Will she take up the offer of friendship?

- “Sunday Afternoon” — Seventeen-year-old Alva has recently finished high school and started working as a maid for the mega-wealthy Gannetts. Today they are hosting a party at their mansion and Alva must navigate a delicate social situation: They want her to feel part of the family, but what does that mean, exactly, when you’re actually the paid help? Alva must also navigate the men who enter the house, several of whom express sexual interest in her. This isn’t your run-of-the-mill, predictable young-woman-is-seduced storyline, but Alice Munro keeps readers in audience superior position as we watch with bated breath what happens to Alva in this big, lonely island of a house. We’re left to deduce most of it.

- “A Trip to the Coast” — An eleven-year-old girl called May lives with her mother and grandmother (mostly her grandmother) in a general store in a three-house township. There’s nothing to do in this one horse town. But today she’s looking forward to same-age company. However, the “company” is a total let-down, and so her grandmother, for the first time ever, suggests the two of them take a trip to the coast. But then another visitor comes. A customer who declares himself an amateur hypnotist. This story ends on a cliff hanger, and I don’t believe Munro has given us enough of a symbolic layer to fill in the gaps for ourselves. I believe we’re supposed to feel exactly as unmoored as eleven-year-old May, waiting out front of the store in the rain.

- “The Peace of Utrecht” — Numerous critics and scholars consider this story the jewel of the crown of Munro’s first collection. Considering that, it’s baffling why it doesn’t make it into more Selected and Collection volumes. It’s certainly the most overtly personal of Munro’s early stories, and she has said in interview that this one changed the way she wrote. Until writing “The Peace of Utrecht” she’d written to be a writer. Now she wrote because she knew only she could write this story. The biographical relevancy: young Alice Munro cared for her mother over many years as her mother lived, then died, with Parkinson’s disease.

- “Dance of the Happy Shades” — An emotionally astute and very observant adolescent girl is required to accompany her mother to an embarrassing recital with the elderly, unfortunate-looking spinster teacher whose spinster sister is recently bedridden due to a stroke. The story is told via the slightly baffled viewpoint of the girl, who is required to recite a tune on the piano at these excruciating annual events.