Blueberries For Sal (1948) is a picture book written and illustrated by Robert McCloskey, also well-known for Make Way For Ducklings. Both stories are thrillers for the preschool set, especially this one. In fact, I’m about to try and convince you that Blueberries For Sal is the inspiration behind Cormac McCarthy’s No Country For Old Men, with blueberries swapped out for drug money.

McCloskey makes use of a number of established thriller genre techniques in this story, and creates an exciting yet cosy tale. How does he accomplish that? Let’s take a look.

SETTING OF BLUEBERRIES FOR SAL

The entire story takes place on a hill in the wilderness of America. Readers who know about the author and how he made it will easily place the story in Maine, as will readers familiar with the sequel, which overtly states the stories of Sal and her mother take place in Maine: err, One Morning in Maine.

It’s worth noting that the family of this story are white. In this particular example, the people are white because McCloskey himself was white and he used his own white family as models. Publishing was almost entirely white back then, and we still have a pipeline problem.

Exploring nature is not some obscure topic in children’s literature. Quite the contrary, children’s literature has a considerable focus on the natural world—on plants and bugs, woods and mountains, animals of every variety. And of the books with this focus, Martin found, the majority of the best-known—from acclaimed older titles such as Owl Moon, Blueberries for Sal, and We’re Going on a Bear Hunt to recent works such as Do Princesses Wear Hiking Boots? and Jo MacDonald Hiked in the Woods—are about white kids. A few (such as The Girl Who Loved Wild Horses and The Not-So Great Outdoors) feature protagonists of color who aren’t specifically African American, but broadly speaking, depictions of black kids as small wilderness adventurers are largely absent from the genre. (Similarly, classic young-adult literature about outdoor exploration or wilderness survival is largely white and nonblack; think Hatchet, My Side of the Mountain, Julie of the Wolves, and Dogsong.)

The Atlantic, Where Is The Black Blueberries For Sal?

Professor Michelle Martin, with a broad handle on the corpus of children’s literature can name only a few examples of Black children playing in nature:

- The Snowy Day (1962)

- Where’s Rodney? (2017)

- Hiking Day (2018)

- We Are Brothers (2018)

Note with a long sigh that 2020 was the year of the Central Park Birdwatching Incident, which is why white readers as well as Black readers need to see Black characters enjoying the great outdoors in picture books, for starters.

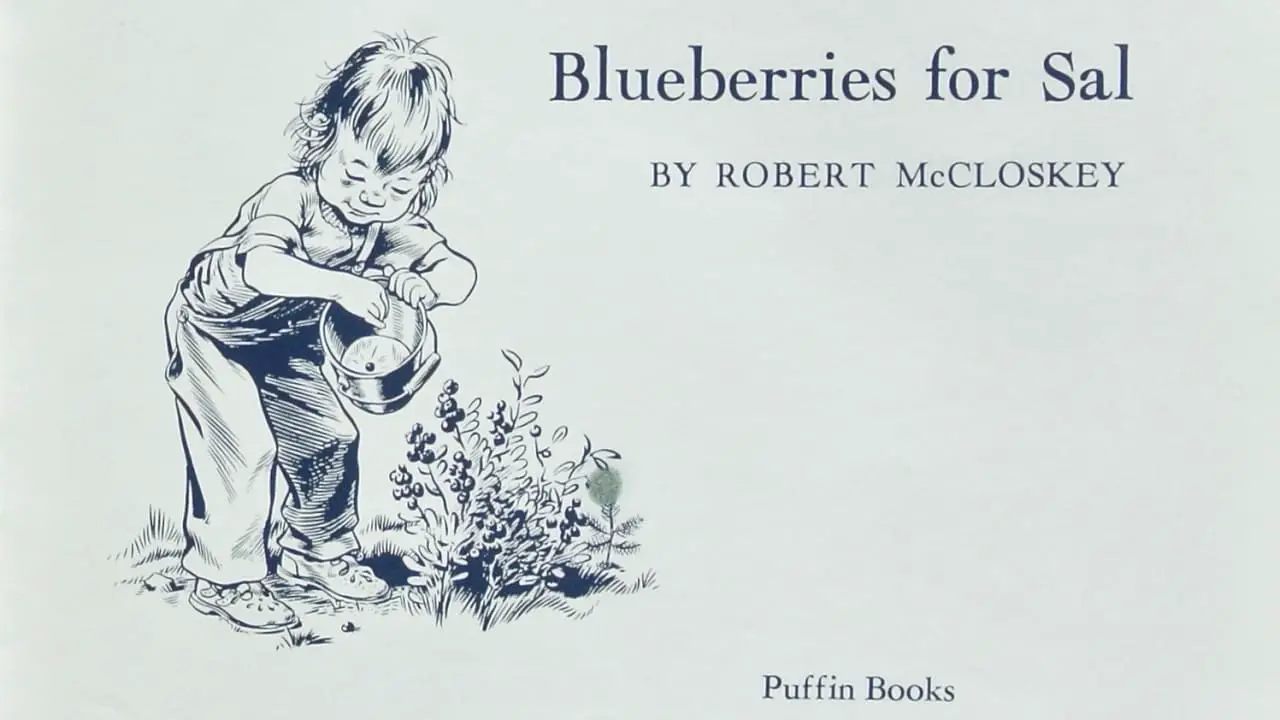

THE COLOUR OF THE INK

I think this is worth saying, only because I’ve noticed a few consumer reviews talk about the ‘black and white’ illustrations. The black is in fact a very deep blue, but at first glance could easily be mistaken for black, and the same could be said for blueberries themselves. If blackberries didn’t also exist, I think blueberries might just as easily have been called blackberries.

STORY STRUCTURE OF BLUEBERRIES FOR SAL

PARATEXT

What happens when Sal and her mother meet a mother bear and her cub? A beloved classic is born!

Kuplink, kuplank, kuplunk! Sal and her mother a picking blueberries to can for the winter. But when Sal wanders to the other side of Blueberry Hill, she discovers a mama bear preparing for her own long winter. Meanwhile Sal’s mother is being followed by a small bear with a big appetite for berries! Will each mother go home with the right little one?

With its expressive line drawings and charming story, Blueberries for Sal has won readers’ hearts since its first publication in 1948.

MARKETING COPY

SHORTCOMING

Sal’s age is important because she is at that developmental stage where she’s old enough to walk off, but too young to understand the danger of walking off, coming face to face with a mother bear who has lost her own cub. Her naivety is her shortcoming, sure, but if she’d panicked and ran, the mother bear may well have chased her down, leading to a completely different outcome. Do you think Sal knows the danger she is in? The text tells us she knows how dangerous bears can be, but does she really? She seems pretty intent on showing the bear those berries.

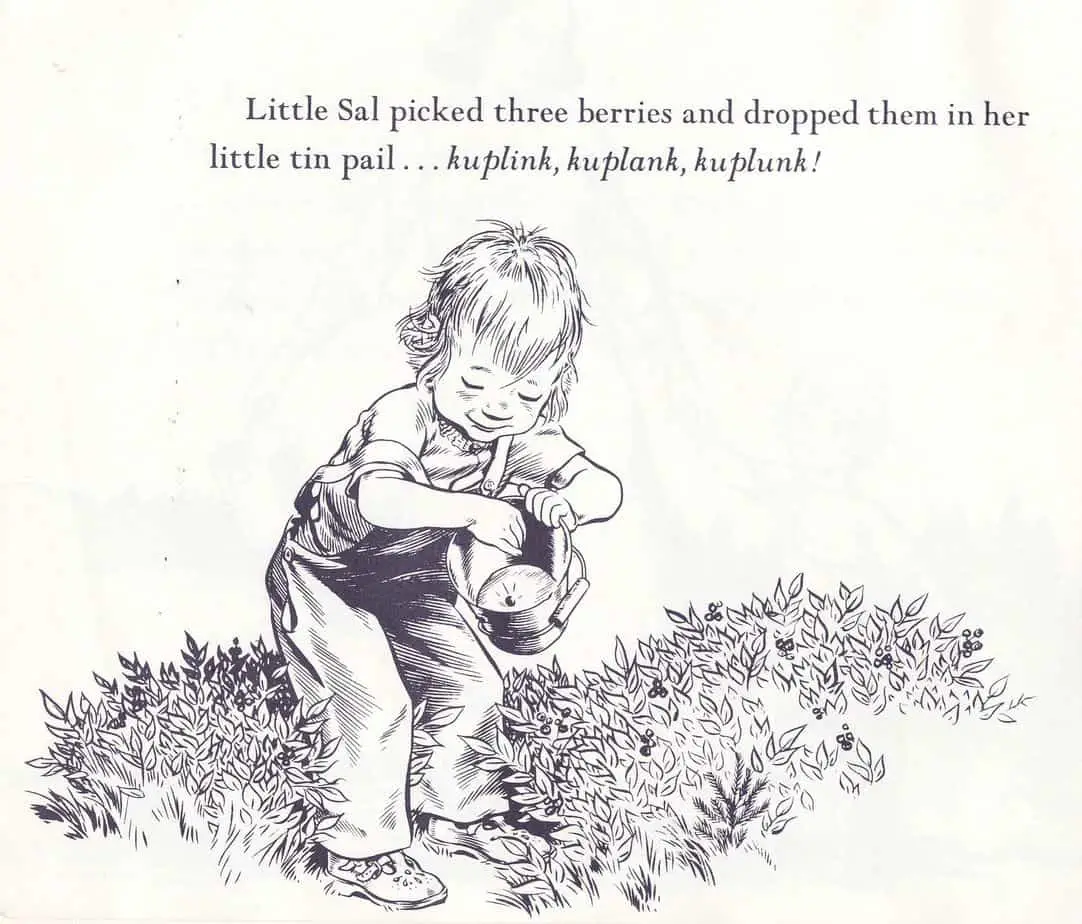

McClosky does a beautiful job of establishing the character of a young child engaged with the sensory world (and not much else). Sal’s design as well as her authentically childlike interests remind me very much of Shirley Hughes’s child characters. McCloskey and Hughes are two examples of authors who really understand the unusual worldview of preschoolers — their interests, their immediate concerns. Not all children’s authors can do that, and many don’t seem to aspire to do that. (To be fair, not all stories call for it.)

In this case, Sal finds great pleasure in the sound of the berries as they hit the bottom of the tin pail. McCloskey makes great use of onomatopoeia with the “kuplink, kuplank, kuplunk!” Contemporary children are more likely to make use of plastic buckets, but I can imagine the exact sound this berry makes on metal.

The term ASMR (Autonomous Sensory Meridian Response) has since entered the popular lexicon, thanks to the Internet and the many ASMR YouTube videos in which users can enjoy satisfying sounds. I just checked — as of today, there are no ASMR videos of people dropping blueberries into a tin pail, clearly an oversight! (Can someone remedy that? I only buy frozen blueberries.)

DESIRE

Sal isn’t that interested in collecting the blueberries for jam. That’s her mother’s concern. Sal, like all children that age, is living in the moment, led by an innate interest in sensory sensations, enjoying the fruit. (Two for me; one for the pail. Relatable.)

OPPONENT

Sal’s first (minor) opponent is her mother. Sal wants to play with and eat the berries in the pail whereas the mother wants to make the most of her time on the hill and collect sufficient berries for jam. I’m sure that mother has plenty of other jobs to do today in the house.

The Minotaur opponent shows up in the form of a bear.

Bill Bryson is wryly terrified of the bear survival advice he received before undertaking his Appalachian Trail expedition which led to his book A Walk In The Woods.

So let us imagine that a bear does go for us out in the wilds. What are we to do? Interestingly, the advised stratagems are exactly opposite for grizzly and black bear. With a grizzly, you should make for a tall tree, since grizzlies aren’t much for climbing. If a tree is not available, then you should back off slowly, avoiding direct eye contact. All the books tell you that if the grizzly comes for you, on no account should you run. This is the sort of advice you get from someone who is sitting at a keyboard when he gives it. Take it from me, if you are in an open space with no weapons and a grizzly comes for you, run. You may as well. If nothing else, it will give you something to do with the last seven seconds of your life. However, when the grizzly overtakes you, as it most assuredly will, you should fall to the ground and play dead. A grizzly may chew on a limp form for a minute or two but generally will lose interest and shuffle off. With black bears, however, playing dead is futile, since they will continue chewing on you until you are considerably past caring. It is also foolish to climb a tree because black bears are adroit climbers and, as Herrero dryly notes, you will simply end up fighting the bear in a tree.

Bill Bryson, A Walk In The Woods, LitHub

Is this bear a brown bear, a black bear or what? I don’t know bears well enough to determine the species without the colour, and for that I am grateful to live in Australia, in which I only need to worry about brown snakes, European wasps, funnel web spiders and red backs (unless I leave the house, in which case the list of hazards grows considerably). (Scratch that, Betsy Bird tells us in their Fuse 8 n’ Kate podcast episode about Blueberries For Sal that this is a black bear.)

PLAN

Let’s talk about the thriller techniques utilised across Blueberries For Sal.

- Heroes of thrillers are Every Men (or ordinary children; low mimetic heroes to use Northrop Frye’s terminology.)

- In a thriller, the hero and the opponent are a good, even match for each other. (In horror, the villain is supernatural, and far more powerful.) In Blueberries For Sal, the mother bear is clearly far more dangerous to Sal than Sal is to the bear, so should we call this horror? No, because McCloskey gets round the serious disparity in dangerousness. The bear has lost her cub, just as Sal’s mother has lost Sal. McCloskey has created the illusion of equal opposition. When applied to thrillers, this technique — of showing the villain as basically the evil flipside of the character — is often called Shadow In The Hero.

- The inciting incident of a thriller is the appearance of the opponent. In this picture book, the inciting incident is the part where the audience is shown that bears ALSO eat blueberries on the hillside.

- The two stories (bears and humans) mirror each other; we know they are about to come face-to-face, but not how or when. This creates tension. Take a thriller story for adults like No Country For Old Men. We see Llewellyn go about his day, and we also see Anton Chigurgh go about his day. We know that eventually they’ll come face to face and tension builds as we wait for it. (Replace the berries with drug money.) Okay so after this, picture book and adult thriller part ways.

THE BIG STRUGGLE

- Though not explicit in McCloskey’s text, Sal seems to get away from the mother bear by distracting her with berries inside the pail. Where does this bear fall on the scale of personification? This is a mimetic bear with human eyes. (Any time illustrators give wild mammals whites, they look human.) The facial expression suggests to me that the bear is smelling the girl. But let’s face it, if you’ve seen a single bear documentary you’ll know this mother knew the humans were there. That said, if we anthropomorphise this bear, she looks comically bowled-over by the ‘sudden’ appearance of the tiny human. Let’s put aside the fact that there’s not much sustenance in berries, and this piece of meat would do nicely for a mother bear, thank you. (I just checked, and Sal is lucky that blueberry picking season does not coincide with coming-out-of-hibernation-season for black bears.)

- Now the scene cuts to the frolicking baby bear, who creeps up on Sal’s mother, still bent over collecting berries. At this point WE DON’T KNOW if the mother bear has munched little Sal for lunch! But McCloskey distracts the reader from such thoughts with humour. He makes use of Reference Humour for preschoolers. (I think we can all remember a time when we were out at the shops, reached up and grabbed the wrong mother’s hand?) Then he makes use of Misplaced Focus, as Sal’s mother keeps picking blueberries, thinking the baby bear is her little daughter. Both jokes appeal to their young, target audience. (For more on humour, see A Taxonomy Of Humour In Children’s Stories.) Adults in picture books don’t tend to be very observant (or curious) — sometimes to their detriment.

ANAGNORISIS

Sal’s mother realises her daughter is missing and I’m sure this would be a freaky tale if we were let inside her head. I mean, if you see a little bear cub you know the mother’s around somewhere, right? No? That doesn’t seem to cross her mind. She calmly and collectedly sets about looking for Sal.

Sal is found, safe and sound.

So that’s the plot tied up. Is there any deeper self-revelation?

NEW SITUATION

The book has opened with a kitchen scene of Sal in the kitchen playing with kitchen implements. The book closes with Sal and her mother making jam together. This suggests their bond has strengthened, if anything. I deduce the mother felt lucky to get her little daughter back safe and sound.

EXTRAPOLATED ENDING

I hope Sal and her family make the most of that blueberry jam because I doubt that mother will be returning next year to collect more berries. Then again, she didn’t seem all that bothered.

I wish I knew where to pick free blueberries. Those things cost a fortune.

RESONANCE

After winning a Caldecott Honor, Blueberries For Sal achieved longevity, and more books in the series. But the next in the series? Not so much.

I see the influence of Blueberries For Sal in various newer picture books. It’s easy to forget this now, without comparing Blueberries For Sal with others of its era, but the character of Sal was refreshingly low mimetic. Girl characters in particular were not typically relatable little kids in children’s books of the 1940s. Instead, the Maturity Formula was in full force, with many prim little example-setters and prissy sidekicks for boy heroes, but few realistic girls. It required a male member of American children’s book royalty observing his own daughter, perhaps, to break that storybook mold.

SEE ALSO