A ‘chosen one’ story stars a main character who is basically ordinary, but because of their bloodline, they are destined for great things. Harry Potter is the iconic example of a contemporary chosen one story. Harry Potter comes after a long tradition.

At TV Tropes you’ll find that Chosen One stories are so popular there are various subcategories.

WHAT DOES SCIENCE SAY ABOUT THE IMPORTANCE OF BLOODLINE?

When we talk about blood we’re of course talking about genetics. We didn’t know this until recently, though scientists had a sense there was some kind of particle which passed traits on.

The 20th century gave us the ‘nature versus nurture’ debate, but anyone who still thinks in those terms is making a folk distinction. Scientists working in genetics today don’t think in those terms at all because, basically, it’s all circular. We now know that environment influences gene expression. Now we know how little we actually know about genes. Sean Carroll describes our early thinking on DNA, once we had a name for it, then goes on to describe how much more complicated it is than that:

If you knew what the DNA was you could predict exactly what the organism was going to be, maybe what kind of food they would like or what kind of occupation they would have later in life. Today we know it’s a little bit more complicated than that. There’s more going on than just our DNA to make up who we are, not only nature versus nurture but even the nature part is very complicated. There’s epigenetics and development factors. There’s mitochondrial DNA. There’s the expression of the different parts of the genes that we have, and so we’re in a very, very rapid state of evolution, as it were, in terms of how we think in terms of how heredity works.

Sean Carroll’s Mindscape Podcast with Carl Zimmer

Separately, I heard another geneticist talking in an interview. I don’t remember who it was or what they were talking about exactly, but one thing stuck in my mind: Geneticists, as a group, don’t tend to be all that interested in ancestry. You won’t find geneticists avidly researching their own family trees. They don’t hang out on the forums of Ancestry.com. That’s a separate interest altogether. Conversely, an interest in genetics seems to make you less interested in where you personally came from, partly because your greater understanding of genetics shows you that we’re all related in one giant web. It seems the story of our collective DNA is far more interesting than any individual’s bloodline.

Maybe we should all get PhDs in genetics and we’ll get some world peace?

FEATURES OF A CHOSEN ONE STORY

The bloodline plot often involves an orphaned character. (Or a character who thinks they are orphaned.) Orphans are super popular in children’s literature, especially in American children’s literature.

Especially in kids’ literature … there’s a trend towards unhappily adopted orphan heroes, as we’ll all know, who are lifted from the abuse/poverty/hilariously wonky living conditions they’re in by discovering that their parents were secretly wizards, or royalty, or holders of some great destiny that Our Hero is now tasked to take up. The truth of their bloodline saves the day, and you can dream of a giant busting through your door declaring “Yer a wizard” and scooping you off into the adventure you were destined for, away from your mundane and terrible home life.

The Afictionado

THE PROBLEMS WITH CHOSEN ONE STORIES

REASON ONE: CHOSEN ONE STORIES ARE UN-DEMOCRATIC

Here’s a spirited argument from Brent Hartinger:

I can’t STAND the whole idea of the “Chosen One” — someone who, usually by virtue of their family background, is destined for greatness. The prophecies all say so!

I’ve hated this trope as long as I’ve been alive. The Force runs strong in the Skywalker family? Harry Potter is a celebrity at the start of his story, destined to kill Voldemorte (or die trying)? Frodo must destroy the One Ring that his cousin/uncle brought back from his adventures, redeeming the family name?

Where does all this leave the rest of us? We’re supposed sit back and let the Chosen One complete his destiny? If we’re lucky, we might get to help?

Oh, goody.

This annoys me because it’s so clearly based on the idea of royalty: that some family lines are simply better than other ones. They’re chosen by God, or the gods, or Destiny itself. (Often, this is couched in the idea that this greatness is some kind of unbearable “burden,” one that must be kept hidden from the ignorant rabble, but that’s mostly just a bunch of bunk. From the point of view of all these stories, the main character is the “cool” kid, even if the actual cool kids can’t see it yet.)

But I believe to the core of my being that greatness is democratic: it’s damn hard, but it’s available to ALL of us.

Brent Hartinger, fantasy author

Bloodlines stories are rarely truly feminist stories. That’s because most stories, even those set in fantasy worlds, work on the principle of patrimony.

It’s the rare novel which subverts this, though some do. One of the earlier subversions happened in On Fortune’s Wheel by Cynthia Voight (1990). As Roberta Seelinger Trites describes:

While Birle [the main girl character] chafes against the narrowness of being female in this feudal society, Orien [her male love interest] questions the entire premise of the feudal society. Rejecting his patrimony, he bitterly tells Birle that knowing who one’s father is does not matter: “I know my fathers, for generations past”. He wonders why patrimony exists and why classes even exist, what gives one set of people the right to rule another, and why women are as disfranchised as they are.

Waking Sleeping Beauty

(Importantly, the story never switches to that of the boy character. He is only ever an accessory to the female character’s self-actualisation.)

REASON TWO: LAZY CHARACTERISATION

Characters of the chosen one archetype are hailed as the most important personin their setting for reasons that are entirely outside their control. The archetype is used to prop up bland characters who have done nothing to earn praise. Because these characters were born better than everyone else, they don’t have to practice or work hard to make a difference. In the Harry Potter series, Harry is worshiped because of what his mother did, while his hard-working friend Hermione sits in his shadow.

Mythcreants

REASON THREE: IN REAL LIFE IT’S NEVER JUST ONE PERSON SAVING THE DAY

Even when one person takes all the glory.

Because the chosen one is destined to change the course of history all on their own, the efforts of a larger community are quickly sidelined or forgotten. In A New Hope, the Rebel Alliance looks incompetent after Luke Skywalker swoops in and takes out an entire deathstar. And unlike many other chosen ones, he actually had some outside experience. By leaving the world-saving to one person, you’ll get a setting that is shallow and simplistic. No one makes history in a vacuum.

Mythcreants

In real life, there’s a human tendency to credit one person with doing all the work of saving the day, especially if that person happens to be a white man. (Compare responses to Chesley Sullenberger, who landed a plane safely ‘all on his own’ to many comments regarding Tammie Jo Shults, attempting to diffuse heroism to all the men in her arena.)

The following responses can be found on any comments section without scrolling far:

“Max Stone’s” element of truth is that many individuals are involved in a rescue operation. The difference is, our dominant cultural narrative gives sole credit only to men. This is how history books end up with far fewer female heroes.

Rather than continue to give sole credit to heroic, individual white men, we should treat male heroes as we currently treat female heroes.

This article from The Atlantic builds a good case: we expect too much of the President of the United States. The job itself has expanded over the decades. This may have something to do with all these (fictional) narratives in which one white dude saves the day, maybe? And now we think that’s how things should work?

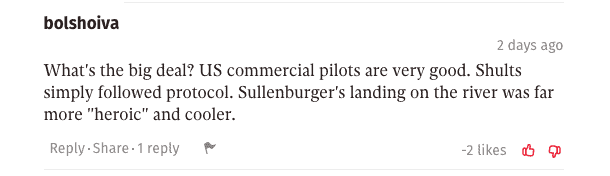

REASON FOUR: THIS KIND OF FLAWED THINKING LITERALLY STARTS WARS

BLOODLINE AND STAR WARS

I am not a Star Wars fan myself, but I would like to include a Twitter thread from someone who is. Star Wars is such a culturally significant story, and says a lot about what a ‘universal’ audience wants from blockbusters.

One of the MANY problems with overvaluing the bloodlines and legacy in Star Wars fandom: I’m a biracial woman of color. Blood purity and legacy when centered on white people has always been about white supremacy.

In worlds where that’s idealized people like me are exterminated. So having that very real inevitable outcome of imperialistic breeding be shown to be flawed and destructive, as well as intrinsically linked to a fascist regime that upholds oppression and exploitation of marginalized people is very validating.

As well as the damaging psychological toll that early indoctrination of children into any organisation, whether it is the Jedi order or the Stormtrooper program. I’m still very disappointed that I have not seen anyone draw parallels between Luke’s early training of Ben and Finn’s abduction into Stormtrooper training. Both of these men were fucked up by the previous generation’s pushing their political and religious aspersions onto kids. Much of the subtext, that I am most likely reading into, the new cast of characters is that this is a generation of war orphans.

Whether they had parents or not, each one of them has been deeply marked by galactic civil war. Poe is a child of the Rebellion, a second generation rebel fighter. That brings with it high expectations, familiar ties to the cause and a still very childish ideation of what he believes heroism is. Rey lives in a literal Emperial graveyard, survives on salvaging scraps from the past. Jakku is such a fantastic subtle marker of how broken the galaxy was left after the last war. It’s quite a contrast to the opulent splendor or Canto Bight. Finn’s a literal child soldier, taken by a war machine fed by wealthy imperialistic interests and political apathy. Rose is deeply marked by the fractured and corrupt galactic politics of this post war universe. Her childhood was stolen in much the same ways as Rey and Finn. Kylo Ren is the ultimate failure of the precious generations, but also the embodiment of generational trauma. Both in the actual abuse his mother suffered under his grandfather, the misguided choice to train him as a child, and the stain of overvalued bloodlines and “legacy”.

I don’t feel like this narrative is mocking of berating it for falling in love with the romantic notions of destiny and heroism. I feel it’s, if a bit sarcastically, redirecting us to what lies beneath these seemingly mystical and wondrous ways in which people change their world. It’s ALWAYS people. Not magic. Not powerful death machines. People shift the tides of war. People save each other. People do this because of love, friendship, family, and faith in a better future. To me this recaptures the magic of A New Hope, but more importantly our first experience of it. Where it was just about random people stumbling their way into friendship and saving the galaxy along the way. Just a farm boy, smuggler, and rebel princess. Anything was possible.

They won not because of magic or machinery. They won because Han Solo couldn’t abandon his new friends, showed up in the very last minute of the big struggle, kicked Vader in the dick, so Luke could blow up the Death Star. Luke didn’t defeat the Emperor using the Force. Anakin Skywalker decided he couldn’t let his son die for a reason. A father chose to save his son’s life. The Lightside of the Force is love and hope. The Darkside is hate, anger, and fear. These are not exclusive to one family, bloodline. Neither is the Force.

Fangirl Jeanne, twitter thread.

DOES THE WORK OF LEIGH BARDUGO SYMBOLISE A CULTURAL SHIFT IN STORYTELLING?

I have reason to believe The Chosen One story is falling out of fashion, but that’s mainly based on observing the career trajectory of Leigh Bardugo. Now, I read a lot of publishing blogs, listen to agent podcasts and whatnot and I’ve never heard any series recommended by publishing people as much as Six Of Crows. Agents love this series. Importantly to my theory: Six Of Crows is not Bardugo’s first fantasy series. What is it about this one that made it take off, and what made it take off at this cultural moment? Bear in mind, most children’s publishing people are lefties:

Six of Crows was radically different from the original trilogy. It had nothing to do with royalty or secret powers or chosen ones or any of the things that people still seem so hungry for—and to be clear, those are all tropes I’ve written and tropes I like, so I get the appeal. But I was in a place where I wanted to talk about characters who the world sees as expendable, not the ones with grand destinies.

Leigh Bardugo, talking with The Mary Sue about moving away from her also popular but not mega popular blood lines stories

IN DEFENCE OF THE BLOODLINE ARCHETYPE

It’s impossible to write about chosen one stories without mentioning Harry Potter. J.K. Rowling’s series is proof that many readers love chosen one narratives. It’s also worth pointing out, because it’s easy to forget, that Harry Potter is now 20 years old. In sociological terms, that’s more than an entire generation. But even in 2018, Harry Potter remains super popular with young readers. Harry Potter is as popular as it ever was. The biggest argument in favour of chosen one stories: Readers love them.

Readers have always loved them, so I’d be surprised if we see the end anytime soon.

Commenter Bruce Hahne points out that the ‘un-democratic’ work ethic implicit in the Chosen One criticism is borne by an equally problematic Protestant work ethic. Taken too far, that, too, can marginalise entire groups of people who are unable to contribute to GDP: Hahne also gives us a brief history of Chosen One stories in popular culture:

Rule out The Chosen One as an origin trope and you kill Green Lantern (all of them), Thor, Harry Potter, Captain Marvel (Billy Batson version), Buffy, and probably about half of Greek mythology.

God also disagrees with you:

“And when Jesus had been baptized, just as he came up from the water, suddenly the heavens were opened to him and he saw the Spirit of God descending like a dove and alighting on him. And a voice from heaven said, “This is my Son, the Beloved, with whom I am well pleased.” (Matt. 3:16-17)

No hard work and right choices there, he was just chosen.

Storytellers use The Chosen One because it works, it continues to work, and movies that use this origin trope well make money.

BLOODLINE STORIES: TIME FOR A MODERN RE-VISIONING?

Some bloodline stories are less problematic than others, or perhaps problematic in a slightly different way. Compare Harry Potter to Matilda:

An interesting case … is Roald Dahl’s Matilda, who off the bat has a lot in common with Harry Potter— a young person in an obnoxious and abusive family who happens to have supernatural powers, both immediately relatable as heroes and providing the wish-fulfilment that we could magic ourselves out of horrible situations we’ve been raised in. Both end up leaving their toxic home environments and end up surrounded by people who love them. There’s a crucial difference between the two, though: Harry is saved by the reveal of his secret and much more appealing family lineage, and Matilda voluntarily leaves her biological family for better prospects.

Harry’s story is a much more common one: your life is terrible, orphan hero? Surprise, your real, but sadly dead and unable to help you, leading to you propelling the plot on your own, family were magical, giving you a portal to a better life you’ve been unknowingly destined for since the get go. This goes all the way back to Oliver Twist, the kicked-around workhouse boy discovered by chance by a rich old man who realises Oliver is his grandson. Happy endings ensue after plentiful struggle. This is a good narrative, and kind of so ingrained in our collective hearts that Matilda’s seems shocking in comparison: she left her blood relatives? But they were supposed to be where the hope was!

Matilda’s happy ending is being adopted, rather than the other way around. She finds someone kind and good, who knows her struggle, and together they rise up against the awful characters surrounding them and go off together to make their own family. Family is redefined as people who love, accept and protect you, and Matilda’s blood relatives are told, narrative-wise and literally, to go stuff themselves.

Afictionado

In other words, J.K. Rowling goes with the ideology that ‘your own family is best’, whereas Roald Dahl and his editor explore the possibility that some families are just terrible and you’re better off rid of them. This is still uncommon in children’s literature, but a surprisingly high proportion of adults are estranged from their natal families. This remains a cultural taboo.

One in 25 adult Australians will be estranged from their family at one point, but it’s a issue that’s rarely discussed openly.

SBS

Afictionado also points out that when we open our hearts to ‘found family’ stories (rather than ‘be loyal to your blood family at all costs’), this paves the way for a more diverse representation of family structure in fiction:

Matilda has a single adoptive mother. Lilo [from Lilo and Stitch] has her older sister, brother-in-law, extra-terrestrial best friend and two cross-dressing alien dads. Steven Universe has three (occasionally five) shapeshifting alien mums and a human dad who supports from the sidelines. Mako Mori has her adoptive father/teacher/saviour, drift companion and an entire army of international pilots and technicians who she’ll heroically protect.

Afictionado

FURTHER READING

“My Father Will Hear About This”: A Look at Magical Aristocracy from Afictionado