“Bliss” is a short story by Katherine Mansfield and one of Mansfield’s last. “Bliss” is offered as an example of a ‘lyrical’ short story.

From a writing point of view, “Bliss” is interesting for its struggle scene, in which the main character experiences purely positive emotions rather than the negative charge which normally goes hand-in-hand with the ‘Battle’ part of a story.

Likewise, the anagnorisis phase is not a SELF-revelation but a plot revelation (more commonly known as a ‘reveal’) which serves to prevent the main character from understanding something deeper about her own psychology. In this respect, “Bliss” is a similar story to Annie Proulx’s “In The Pit” (though in every other respect the stories are nothing alike).

It is possible to read this story many times at different levels and on each reading to notice a new detail. It did much to establish Katherine Mansfield’s reputation as a ‘modern’ writer. Although Virginia Woolf despised it, T.S. Eliot and others regarded it with considerable interest. There is clever satire in the grotesque caricature of the London/Garsington intelligentsia, yet there are moments of quite lyrical beauty and colour which impress themselves on the mind with vivid clarity. Through the character of Bertha, Katherine Mansfield explores the nature of the feminine friendship and female sexuality, both of which are recurring preoccupations in much of her work. Underneath the brittle sophistication the reader senses the underlying tension as it mounts to its disquieting climax.

Katherine Mansfield: The woman and the writer by Gillian Boddy

What Happens In “Bliss”?

Thirty-year-old Bertha Young is blissfully happy, preparing to spend the evening with bohemian, artsy friends who arrive for a dinner party at her house in London. At the end of the evening she catches sight of her husband and friend in the entrance hall and realises that the two are having an affair.

Connection To Mansfield’s Own Life

Mansfield wrote “Bliss” only one week after a haemorrhage which indicated the seriousness of her lungs.

I can’t imagine Mansfield’s state of mind at that time — surely not entirely blissful? Or perhaps Mansfield was experiencing some emotional ups to counterbalance the downs. She did write to her husband, John Middleton Murry, that her awareness of nature had heightened after her terminal diagnosis. Perhaps news of your own impending death can be enough to give you something akin to a psychedelic hit, alongside all the other emotions.

It is quite possible to achieve a state of bliss without chemical input. In his book How To Change Your Mind, Michael Pollan mentions breathing techniques and meditation as other ways of accessing this part of our brains. Apart from deliberate and focused efforts to achieve a state of bliss, bipolar disorders include manic states which present as the flip side of unbearable lows. The human brain has the capacity for extremes of emotion. Most of us coast along in the middle on an ordinary kind of day.

A scene starts in one place emotionally and ends in another place emotionally. Starts angry, ends embarrassed. Starts lovestruck, ends disgusted.

Jane Fitch, from 10 Rules For Writers

A Mushroom Diversion

I am inclined to go a bit off-piste in my interpretation of this short story. (My unimaginative English lit tutor thought so.)

FTR, I don’t seriously think Bertha is high because she ingested something, but revisiting “Bliss” did leave me wondering: Did young New Zealand bohemians know about mushrooms in the early twentieth century? Though Mansfield grew up in New Zealand, this story is set in England. Were they used recreationally in England in the early 20th century?

Psychedelic mushrooms aren’t mentioned in New Zealand literature until almost 100 years after Mansfield’s birth, but obviously people knew about them long before mycologists were writing them down in books.

New Zealand has its own varieties of magic mushrooms endemic to New Zealand. I can’t easily find information on magic mushroom use among Māori populations prior to European arrival, but mushrooms were a small part of traditional Māori diet. (Wood ear was eaten by Māori people, who called it “hakeke”.) Surely at some point someone tried an hallucinogenic mushroom and discovered its powers by accident. That said, Māori didn’t really like mushrooms and ate them only when nothing else was about. (Unlike Chinese people, say, for whom mushroom is an important part of the diet.)

European New Zealanders didn’t seem to know much about magic mushrooms until the 1980s, after news of the psychedelic era in America had been widely disseminated. (In pre-Internet days these things took a while. Plus, New Zealand was always England focused rather than America focused until about then.)

Still, I’m left wondering, partly with facetious interest, if Mansfield ever went for a mushroom scavenge on Mt Vic. Wellington is said to be magic mushroom capital of New Zealand and would have been the perfect place for Bertha to experiment with psilocybin. This housewife seems high on something.

Okay, here’s my argument, though:

Colours seem to pop for Bertha. She notices how different objects match because of a shared hue: the fruit with the carpet, Eddie’s scarf with his socks. She’s seeing patterns where most people would not make note of such coincidence.

She’s noticing small details in the way of a child, as reported by users of psilocybin.

Michael Pollan describes an intense experience with a tree, and Bertha really has a thing for that pear tree.

Bertha is on a different emotional wavelength from her husband. Her husband wants to talk to her about time — about putting dinner off for an extra ten minutes — but Bertha seems to have lost her awareness of time passing until he calls, and his mention of it irritates her somewhat.

She sits up and feels ‘quite dizzy, quite drunk‘. (This indicates some kind of altered state doesn’t line up with a typical psilocybin experience, in which case the body feels heavy.)

Mrs Norman Knight seems to shapeshift into a ‘very intelligent monkey’ even after taking off her coat with monkey decorations on it.

The dialogue of Bertha’s guests is quite strange, made up of fragments rather than full thoughts, which may be how Bertha hears it: “I have had such a dreadful experience with a taxi-man; he was most sinister. I couldn’t get him to stop. The more I knocked and called the faster he went. And in the moonlight this bizarre figure with the flattened head crouching over the lit-tle wheel . . . “

If Bertha had been up on Mt Vic, I know who she was with earlier. Her wonderfully camp friend Eddie. Eddie has also lost all concept of time. “I saw myself driving through Eternity in a timeless taxi.”

She has to try hard not to laugh at something that’s not all that funny (‘Face’s funny little habit of tucking something down the front of her bodice–as if she kept a tiny, secret hoard of nuts there’.)

Mansfield’s creation of Bertha is in some ways a fictional recreation of herself. She is satirising the very same social set she herself was a part of — bohemian arty types sharing big (ridiculous) ideas for one-act plays (a ripe genre for making fun of), and decorating a room in absurdist fashion — ‘a fried-fish scheme’. The narration is what we’d now call ‘close third person’ — we see this dinner party through the viewpoint of Bertha and Bertha alone. If Bertha is making fun of her own bohemian friends, she’s feeling separated from them. You could describe her as being on her own planet. (Mansfield referred to her character of Bertha as ‘artist manqué‘, meaning an artist who has failed to live up to expectations. She and her friends seem drawn into Emperor’s-New-Clothes ridiculousness posing as art.)

“You’re of course, absolutely right about ‘Wangle’. He shall be resprinkled mit leichtern Fingern, and I’m with you about the commas. What I meant (I hope it don’t sound high falutin’) was Bertha not being an artist, was yet artist manqué enough to realise that those words and expressions were not and couldn’t be hers. They were, as it were, quoted by her, borrowed with… an eyebrow… yet she’d none of her own. But this, I agree, is not permissible. I can’t grant all that in my dear reader. It’s very exquisite of you to understand so nearly.”

Letter to Murry, March 14, 1921

- She’s feeling this (wholly imagined) connectedness to Pearl Fulton. She’s lost some of her sense of ego.

But as Mansfield showed us in “A Windy Day”, adolescence can feel like that too. Hormones can do it. Bertha is a thirty-year-old housewife but she has not yet come of age. She has yet to experience sexual awakening. Her name is literal and symbolic: Bertha Young.

Bertha is likely bisexual, as was Mansfield. What she’s feeling towards Pearl seems simple erotic attraction, though Bertha is reading a whole lot of mystical meaning into it. A character such as Bertha wouldn’t have known the word or the concept ‘bisexual’. This is Bertha trying to make sense of her attractions.

Freudian Stuff

Mansfield is known for her Freudian themes. At this point in her life especially, she’s interested in repression.

REPRESSION

Up for debate: Did Bertha know that her husband was having an affair with her friend?

“How idiotic civilisation is. Why be given a body if you have to keep it shut up in a case like a rare, rare fiddle?”

Could Bertha have known all along about her husband’s affair with Pearl? Mansfield explores the psychology of repression in “The Fly”, written just before she wrote “Bliss”, in which an old man has developed techniques for avoiding any sort of thoughts about his only son killed in the war. When Bertha tells herself that her husband rushes after Pearl because he feels bad about some social sleight, this could be part of a bigger story she tells herself about Harry: How his meanness is really just him being funny, and he’s the sort of man one has to get to know. The irony is, Bertha herself doesn’t know her own husband.

NARRATION

The story works through symbolism, carefully selected detail and the clever unobtrusive fusing of the central character and narrator.

Gillian Boddy

The elliptical narrative style of “Bliss” would support the view that Bertha can’t finish a full thought. The question is, why not? Oftentimes Bertha cannot finish her next sentence and allows herself to be distracted. Perhaps the reality of her life is too uncomfortable.

Take the first paragraphs. Bertha speaks as if observing herself from a distance. Her words are not her own. She thinks one thing then immediately edits herself, as if observing herself taking part in some drama. Her words are simply a collection of quotations, gleaned from elsewhere.

Much use is made of dots and dashes, throughout Mansfield’s work, but especially in this story. Bertha’s feelings are reproduced in breathless, repetitious sentences. The broken syntax — full of dashes and exclamation marks — make the language seem (faux-)spontaneous, like someone thinking out loud, or like someone doggedly determined to live in the moment (and therefore avoid putting uncomfortable pieces of evidence together… the husband late home, who arrives at the same time as Pearl…)

Symbolism and Imagery of “Bliss”

THE PEAR TREE

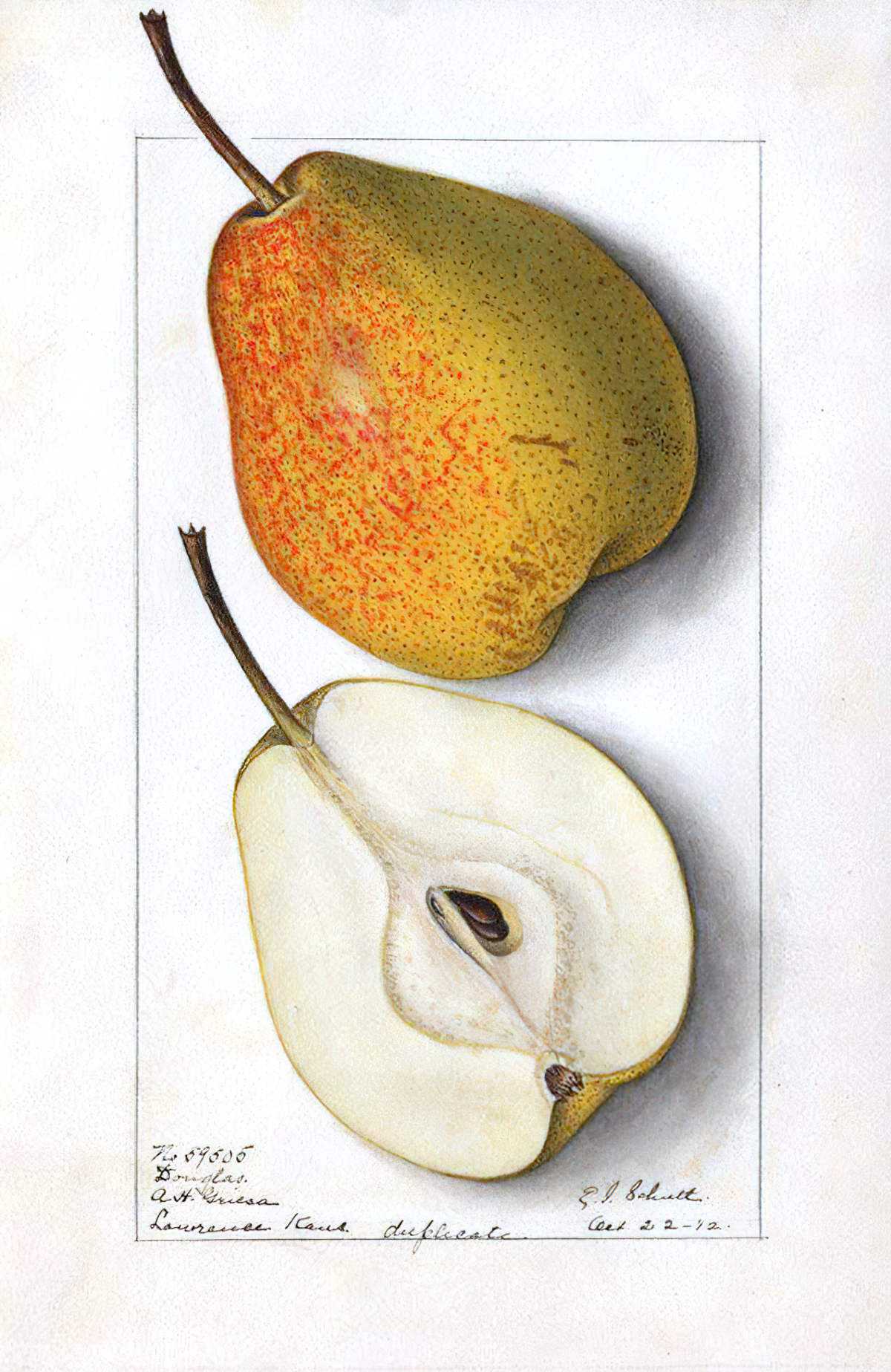

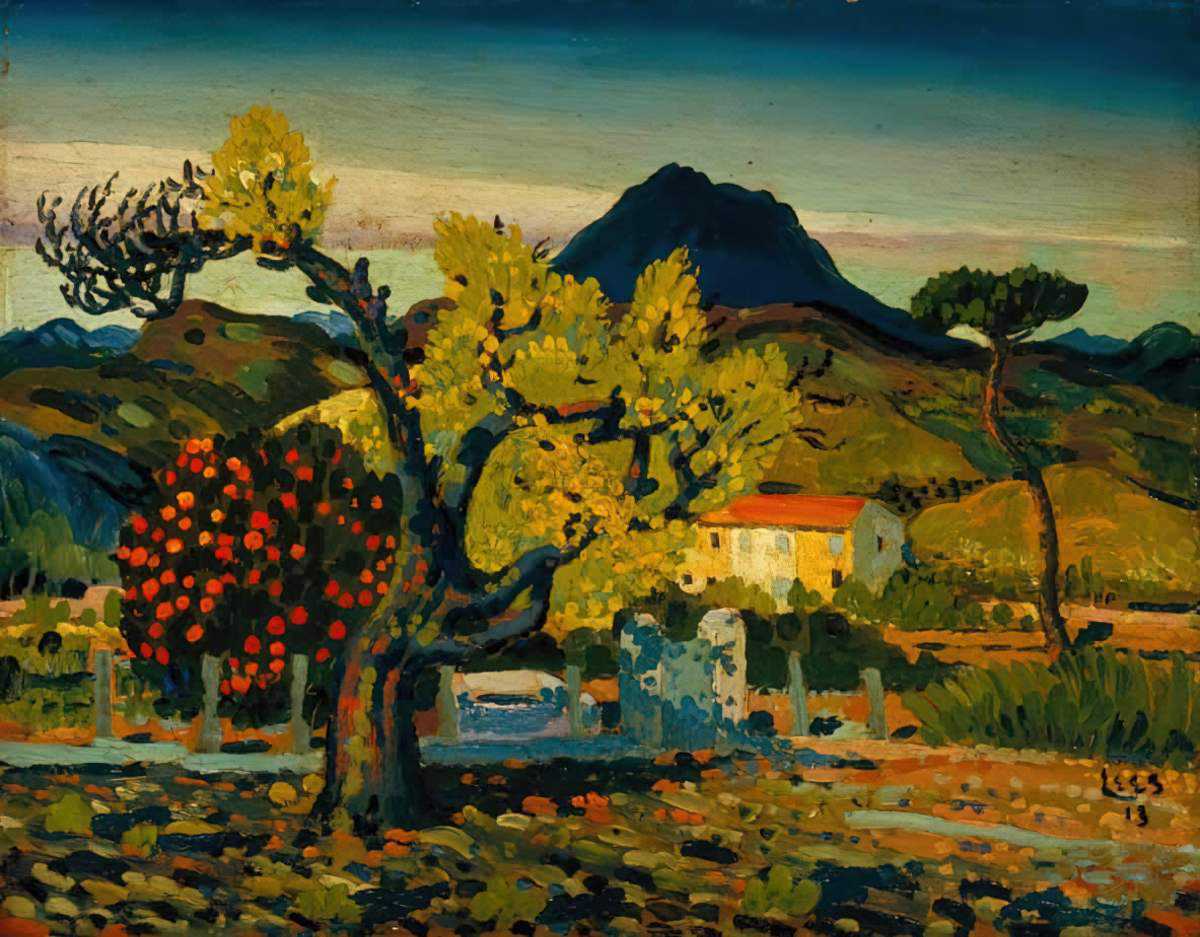

In Mansfield’s short stories, birds, trees, insects and objects are often introduced by means of a precise comparison e.g. the pear tree in “Bliss”: ‘At the far end, against the wall, there was a tall slender pear tree in fullest, richest bloom; it stood perfect, as though becalmed against the jade-green sky’.

What of the two cats? The beauty is somewhat diminished by the appearance of the cats — one is grey and pregnant, the other black, following like a shadow.

Some have said the pear tree is a phallic symbol. When both women look at the tree they’re both looking at Harry. I may have gone awol on a psilocybin interpretation, but I think this is a bit of a stretch. Almost everything can be phallic in literature.

The pear tree could be a symbol of nature’s indifference to human suffering.

Or the tallness of it may represent Bertha’s homosexual aspirations, realised suddenly to their fullest. The flowering of the tree could symbolise the flowering of her sexual feelings. ‘[Bertha] seemed to see on her eyelids the lovely pear tree with its wide open blossoms as a symbol of her own life.’ Across literature, blossoms are a common symbol of sexual maturation and release. The flowering tree could be a symbol of Bertha’s life, and the image of the cat appears once more after Bertha realises her husband has been unfaithful.

Combine these possible meanings, the tree might represent masculinity after all — the tree is tall and assertive and represents the ‘masculine’ part of Bertha’s sexual desire.

Bertha herself isn’t quite sure about the significance of the tree, and the symbolism of the tree remains only vague to the reader.

- The first mention of the pear in storytelling is in Homer’s (9th century BC) epic poem, The Odyssey.

- You find pears, apples and figs throughout Christian iconography, probably as a metaphor for any kind of sacred tree. It frequently appears in connection with Christ’s love for humankind.

- Paintings of pear were found in the ruins of Pompei.

- Elsewhere in the world the pear means a wide variety of things. China: justice, longevity, purity, wisdom. Korea: grace, nobility, purity, comfort. Also good for female fertility, health, and sitting exams. The flower is meant to resemble the face of a beautiful woman. But the transience of petals is a metaphor for the sadness of departure. In many other parts of the world the pear symbolises the human heart, which it kind of resembles.

- Pears need to be cross-pollinated. A lone pear tree won’t give you any fruit, or reach ‘its potential’.

- People hasten fruit bearing by causing the tree damage — “punishing” them — driving iron pegs into the trunk and so on. Pear trees are therefore associated with pain.

- Pears are associated with temptation. The Bible talks about an apple in the Garden of Eden, but actually the name of the fruit tree is not mentioned in the biblical text. 13th century illustrations suggest apples. Two hundred years later everyone thought it was an apple. But honestly, that fruit could just as easily have been an early variety of pear.

- When did the pear make it to Europe? We don’t know exactly. It may have been independently domesticated or it could have been introduced by the Greeks who founded Marseille in 600 BC. Most likely, it was introduced by the Romans. Charlemagne gets the credit for establishing the first collection of pear in France. Charlemagne was the rules of the Franks in the ninth century — so, the early medieval period.

- By the late 1500s pears were common in England. Shakespeare makes a few references to pears. He didn’t seem to like them much. Maybe the bard accidentally picked a stewing pear and tried eating it raw? Who knows. He certainly considered the pear phallic, kind of like how bananas are commonly considered today. ‘As crest-fallen as a dried Pear…I must have saffron to color the Warden pies… O, Romeo… thou a Poperin Pear.’ (A sexual euphemism — ‘pop her in’. (Another fruit I’ve never encountered, the medlar, was thought to resemble an ‘open arse’, actually referring to the vagina. The medlar is Persian, and closely related to the pear.)

- Pears are closely associated with France. Pears were really popular from the 16th to 19th centuries, where many varieties were cultivated.

- They fruit from May to December in the Northern Hemisphere, so are associated with that time of year.

- Charles Dickens also used pears as sexual metaphor. From David Copperfield: ‘I suppose you have sometimes plucked a pear before it was ripe, Master Copperfield? I did that last night, but it’ll ripen yet! It only wants attending to. I can wait?’

- ‘Pyriform’ means ‘pear shaped’, but this refers to European pears. Asian pears are round and crisp (think of the nashi). Asian pears don’t need to be softened before eating.

Sun and Moon Imagery

Mansfield like sun and moons in her stories, and even named one story “Sun and Moon”. In “Bliss”, the earlier imagery for Bertha’s happiness is symbolised by a series of sun images. Later in the story, the sun image is linked to the moon (via a candle metaphor). This suggests prelapsarian innocence – i.e. before the world is supposed to have turned to shit. (Lapsarian refers to the Fall of Man — a Calvinist idea.)

HEAT AND COLDNESS

Mansfield returns to images of hot and cold throughout “Bliss”, referring back to ‘that bright glowing place – that shower of little sparks coming from it’. As the story progresses, the metaphor of sun and sparks becomes a form of shorthand for Bertha’s state of mind, and perhaps of her eventual ‘seeing the light’.

STORY STRUCTURE OF “BLISS”

SHORTCOMING

Anthony Alpers, who wrote The Life of Katherine Mansfield, believed the women in this story are humanised whereas the man are types.

Bertha is young, naive and perhaps repressing the reality that her husband and friend are in love.

DESIRE

Bertha wants to enjoy a dinner party surrounded by interesting friends, and by one friend in particular — a beguiling young woman.

OPPONENT

Character webs become more interesting when opponents and allies are not who they at first appear to be. Bertha thinks Pearl is an ally, but it is eventually revealed that she is a firm romantic opponent. (As is her husband, Harry.)

PLAN

Because Bertha is in a blissful mood, she’s not really in ‘planning’ mood. Matilda of “The Wind Blows” is similarly driven by her mood. Bertha flits from one blissful thing to the next, remaining deliberately in the moment. There’s nothing sequential or logical about her party planning, but we assume she made at least some of the arrangements. (I suppose cook was out back making the soufflés, though Bertha takes credit for ordering them.)

BIG STRUGGLE

Underneath the brittle sophistication the reader senses the underlying tension as it mounts to its disquieting climax.

Gillian Boddy

Which is the ‘big struggle’ scene in “Bliss”?

In a Mansfield short story, the big struggle scene is probably some emotionally charged moment. The big struggle scene in this story is the strong image of two women staring at the same pear tree. We don’t know this until later, but they’re looking at the same man. This scene is an interesting example of a ‘big struggle’ scene which contains the direct inverse of what we’d normally expect from a big struggle — Bertha is filled with utter joy. Not fear, not anger, nothing negative. Joy. But that joy has a certain big struggle-like rugged determination about it. She is determined for Pearl to be joined to her in spirit. This is reminiscent of your archetypal big struggle.

ANAGNORISIS

Perhaps Mansfield does a bit of a bait and switch when it comes to the anagnorisis (which is more of a plot revelation than a deeper understanding of Bertha’s own self). We might expect that by the end of this story Bertha will have come to understand her attraction to Pearl as sexual. The reader can clearly see this situation for what it is, yet Bertha cannot.

But no. She has no such anagnorisis. Her anagnorisis is cut-off short. Instead, her revelation is that her husband is in love with her friend (to whom she is also attracted). I put that very deliberately in parentheses.

This is especially bad timing for Bertha, whose sexual attraction for Pearl has prompted — for the first time ever — a sexual attraction for her own husband.

NEW SITUATION

The abrupt ending leaves the reader wondering what will happen to Bertha now that she finally understands the irony of that bliss that earlier ‘she did not know what to do with’. Will she finally grow up— or is she trapped in this deceptive world of polite pretence?

While a plot-driven story would offer the satisfaction of narrative closure — a definite ending — nothing is finally resolved in “Bliss”. Not overtly, anyhow. We have to read the symbols.

Mansfield’s imagistic patterns are important in that they suggest various levels of meaning not always inherent in the action of the story, create ironic contrasts and support themes with rhetorical figures.

Julia van Gustaren, Katherine Mansfield and Literary Impressionism

Certainly, Bertha is shattered and crestfallen. But Mansfield ends not with Bertha but with the pear tree, the story’s central image. The pear tree hasn’t changed at all, juxtaposing with Bertha’s extreme change in emotional valence.