pretty awful how baseline human activities like singing, dancing and making art got turned into skills instead of being seen as behaviors

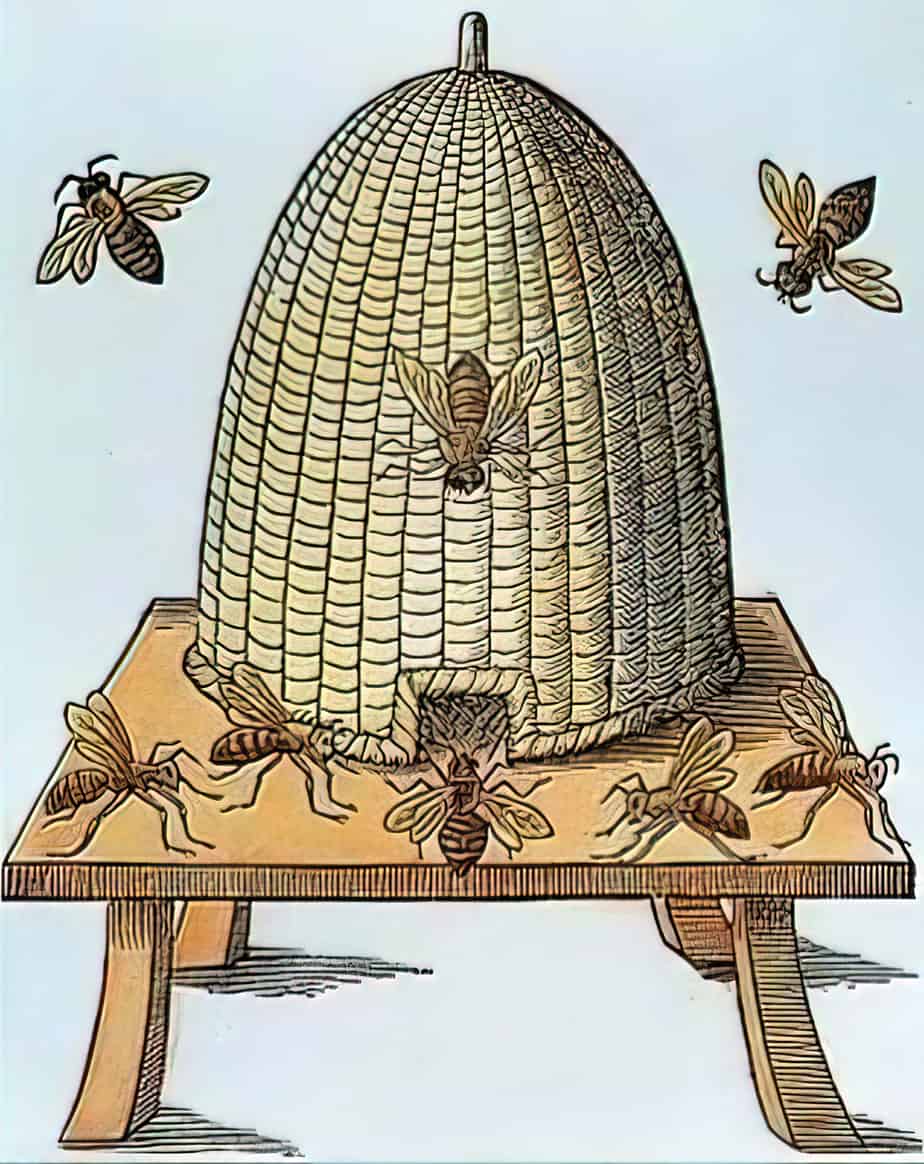

so now it’s like ‘the point of doing them is to get good at them’ and not ‘this is a thing humans do, the way birds sing and bees make hives’

goldhornsandblackwool

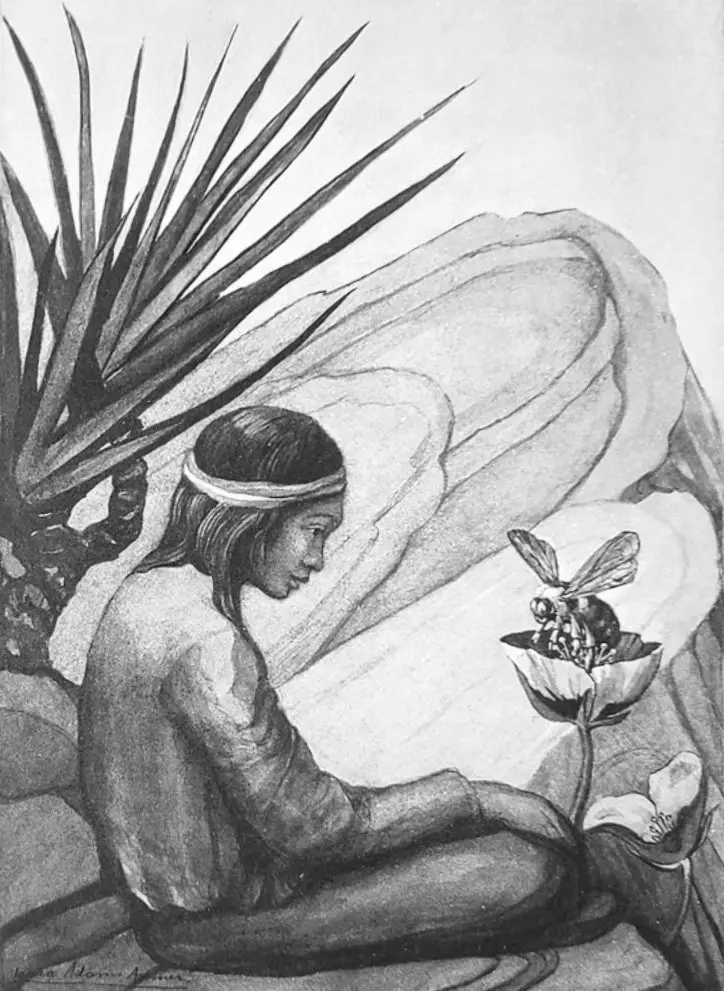

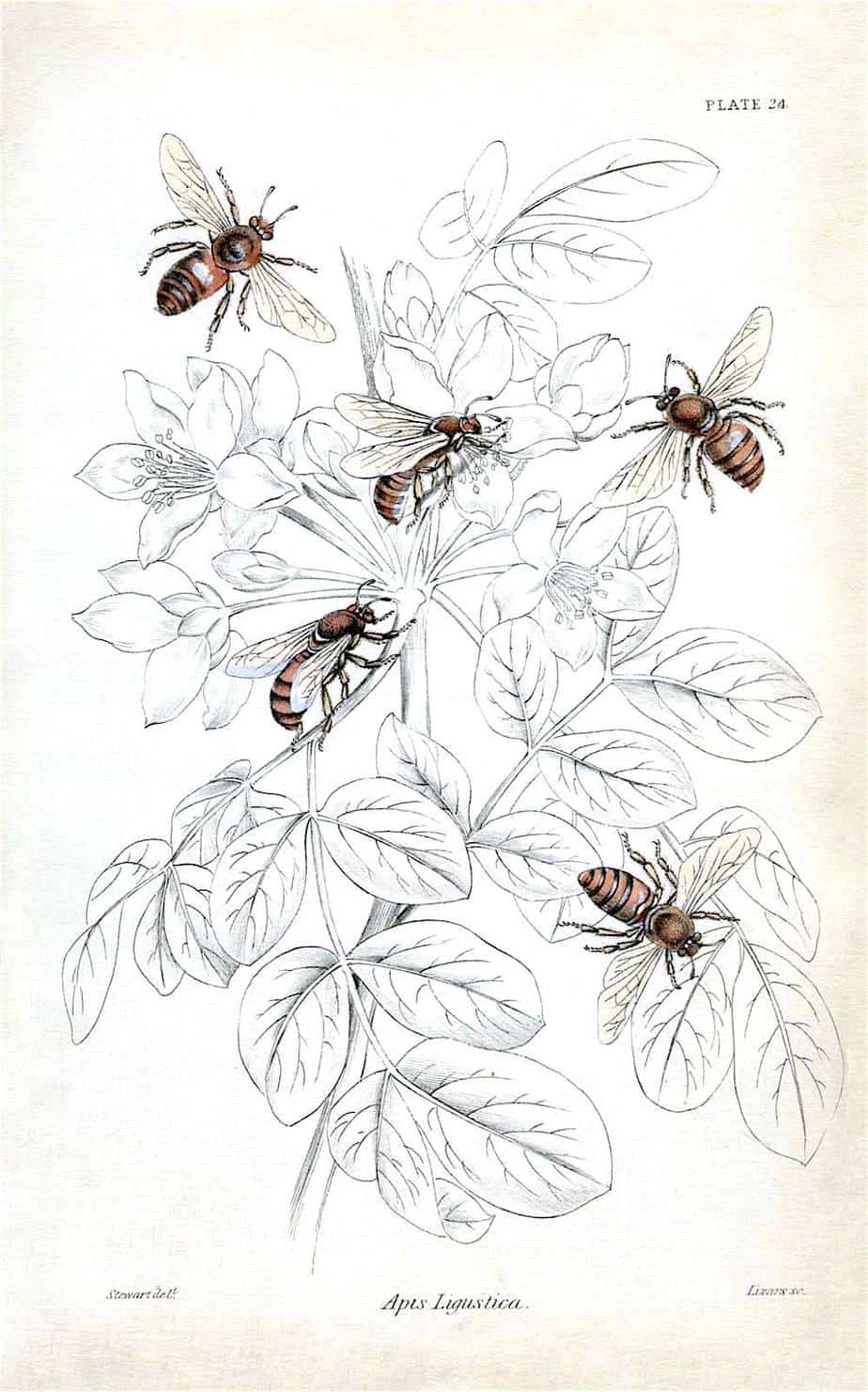

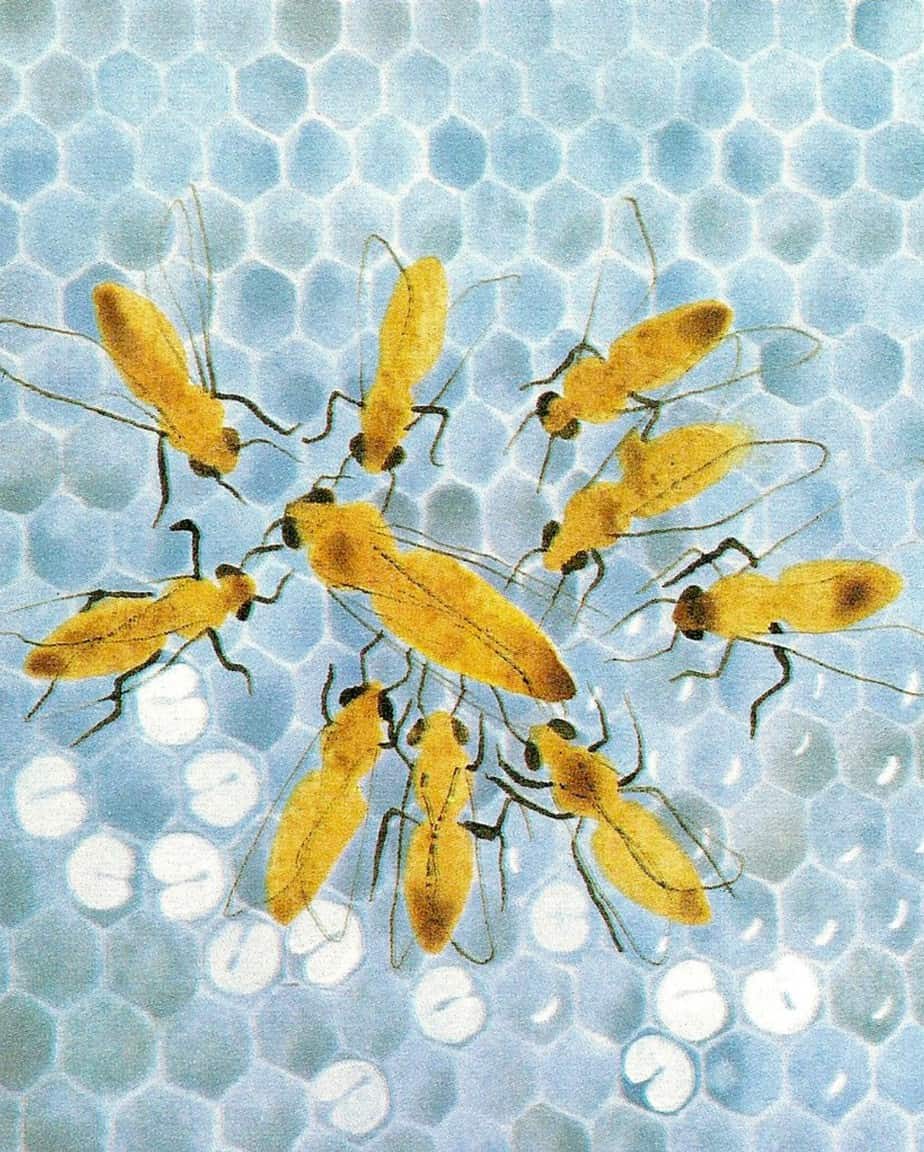

Bees are strongly associated with flowers. Bees didn’t exist until flowers existed, although wasps did.

Honey is one of the oldest known preservatives and our first sweetener.

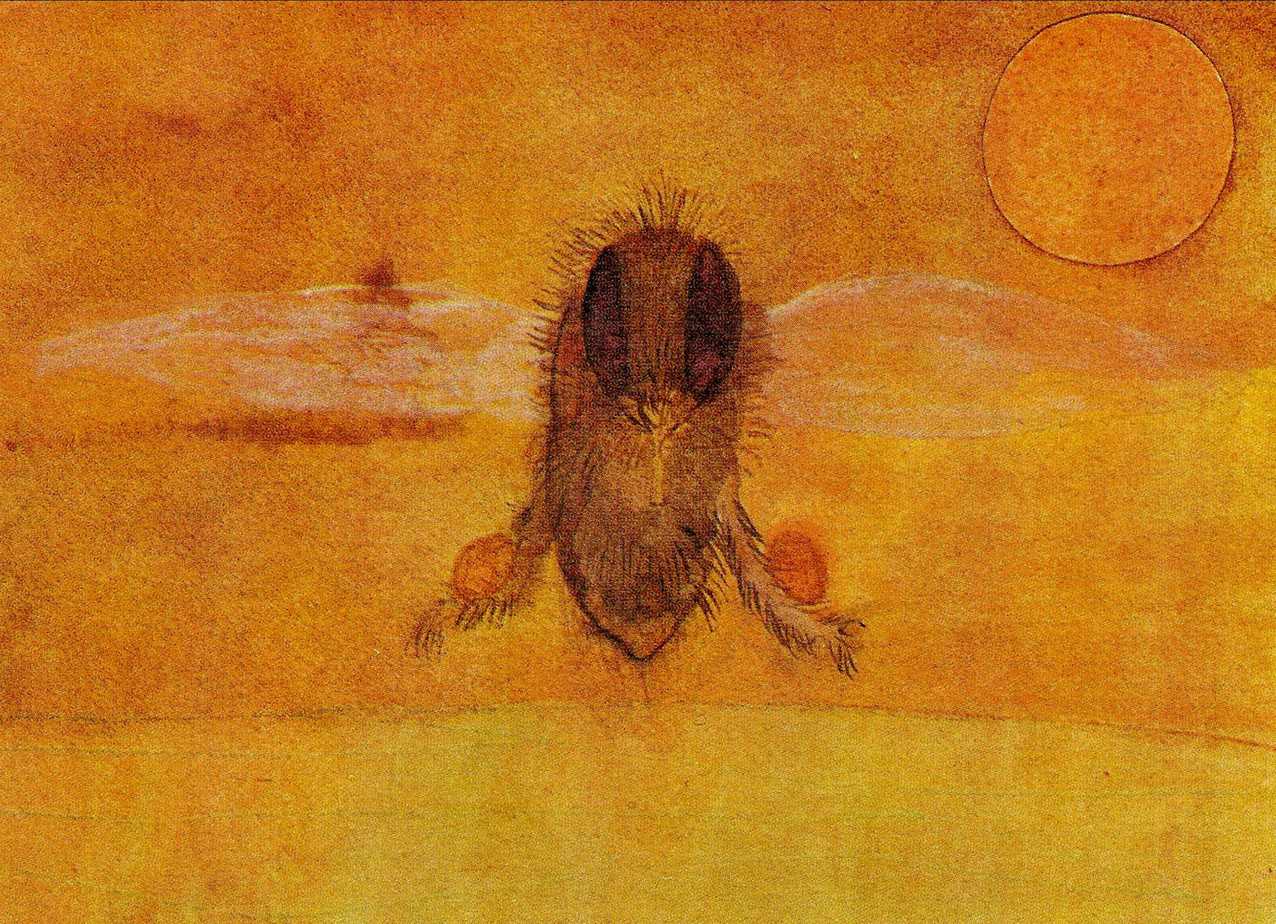

Bees are associated with gods and goddesses all around the world. The humming of bees might be interpreted as the voice of the Goddess, as she is considered evident in all parts of creation.

Symbolism overlaps with that of butterflies. Depending on time and culture, bees represent transformation and also the human soul, ephemeral and fleeting, transitioning between life and death.

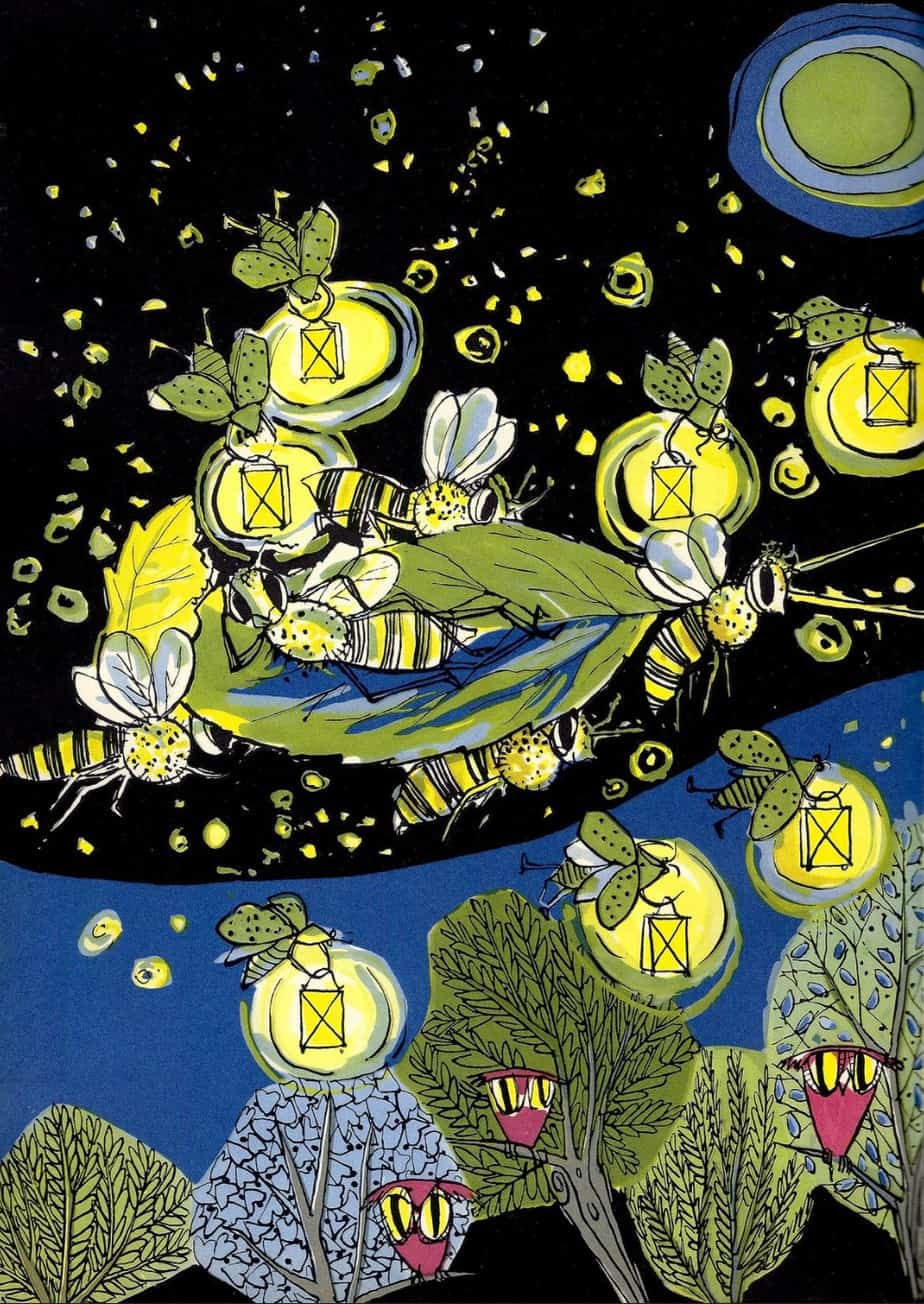

According to some historians, the Celts came to Britain specifically for the black bee and its honey. Britain was known as the Isle of Honey due to the huge number of wild bees flying about. The Celts believed bees to have great wisdom, acting as messengers between worlds.

Here in Australia, Aboriginal cave paintings of bees date back to ~10,000BCE. These paintings also seem to include images of men carrying bags of honey over their shoulders.

Most people in Adams, New Hampshire, know me by name, and those who don’t, know to steer clear of my home. It’s often that way for beekeepers—like firefighters, we willingly put ourselves into situations that are the stuff of others’ nightmares. Honeybees are far less vindictive than their yellow jacket cousins, but people can’t often tell the difference, so anything that stings and buzzes comes to be seen as a potential hazard. A few hundred yards past the antique Cape, my colonies form a semicircular rainbow of hives, and most of the spring and summer the bees zip between them and the acres of blossoms they pollinate, humming a warning.

I grew up on a small farm that had been in my father’s family for generations: an apple orchard that, in the fall, sold cider and donuts made by my mother and, in the summer, had pick-your-own strawberry fields. We were land-rich and cash-poor. My father was an apiarist by hobby, as was his father before him, and so on, all the way back to the first McAfee who was an original settler of Adams. It is just far enough away from the White Mountain National Forest to have affordable real estate. The town has one traffic light, one bar, one diner, a post office, a town green that used to be a communal sheep grazing area, and Slade Brook—a creek whose name was misprinted in a 1789 geological survey map, but which stuck. Slate Brook, as it should have been written, was named for the eponymous rock mined from its banks, which was shipped far and wide to become tombstones. Slade was the surname of the local undertaker and village drunk, who had a tendency to wander off when he was on a bender, and who ironically killed himself by drowning in six inches of water in the creek.

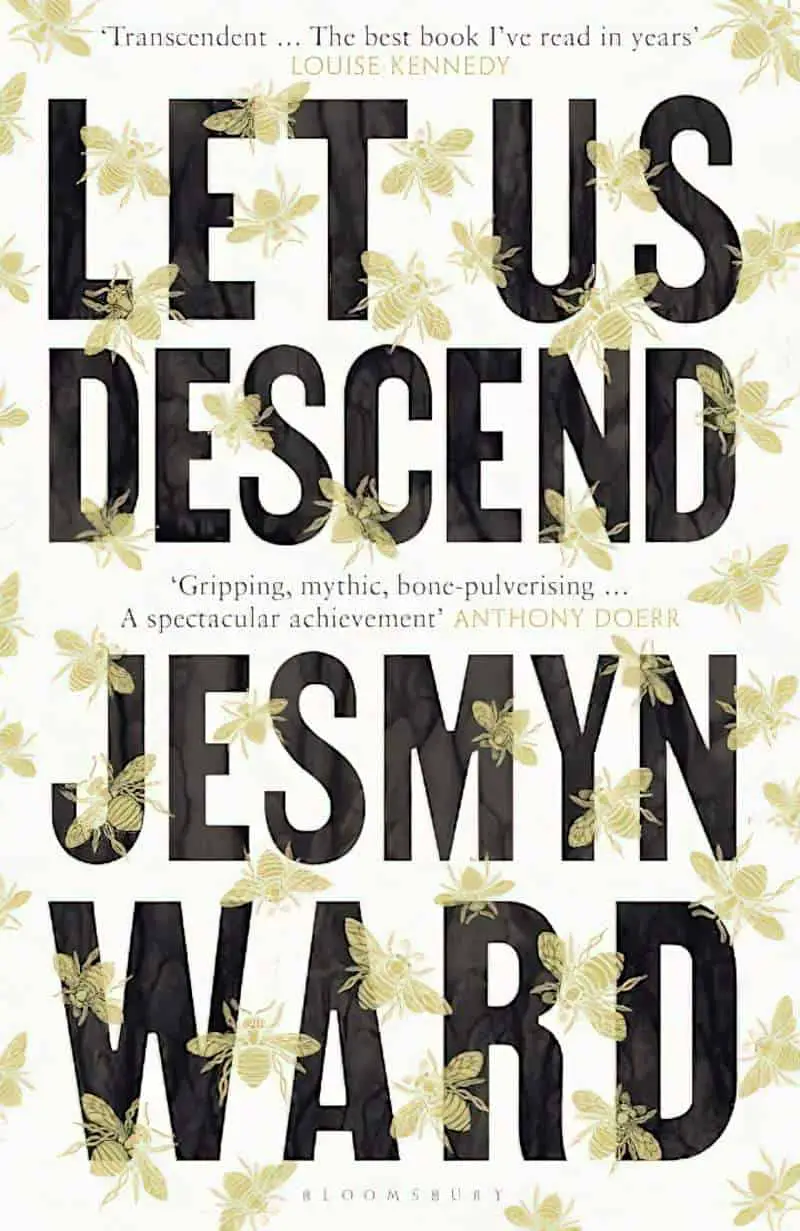

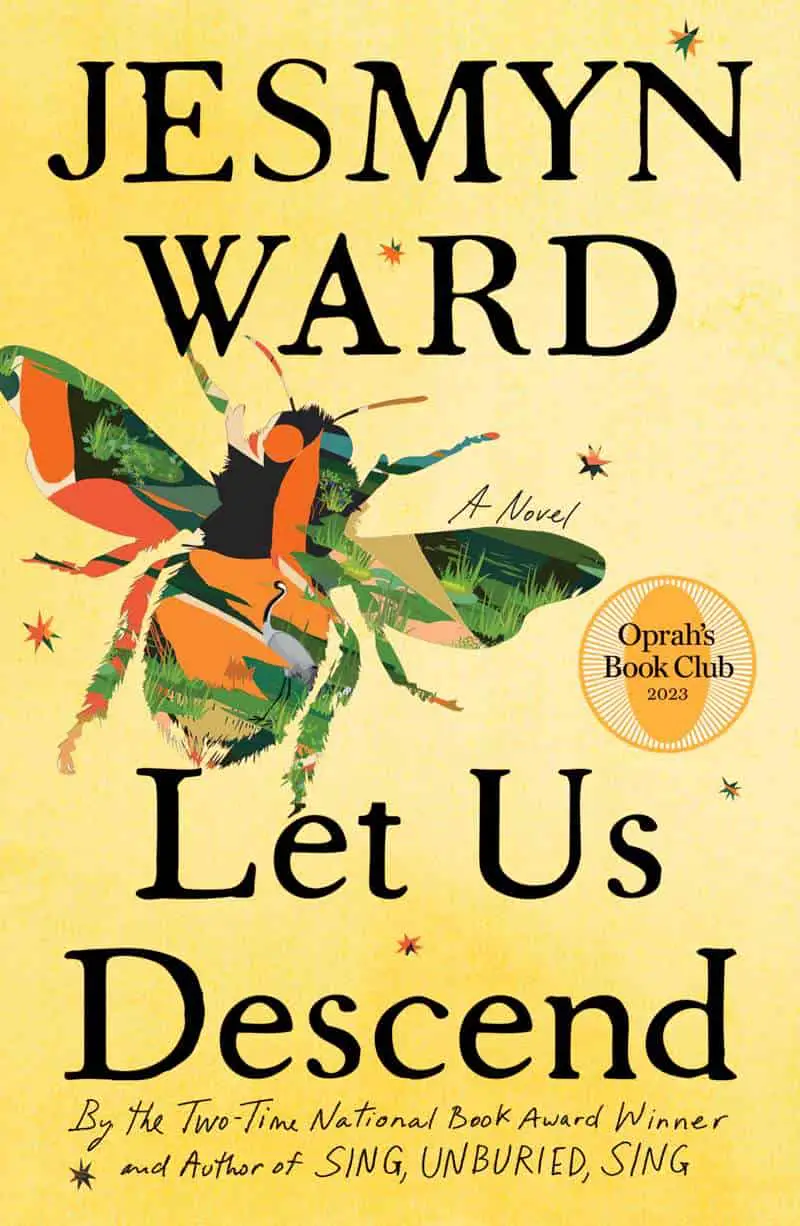

from the opening of Mad Honey, a 2022 novel by Jodi Picoult and Jennifer Finney Boylan

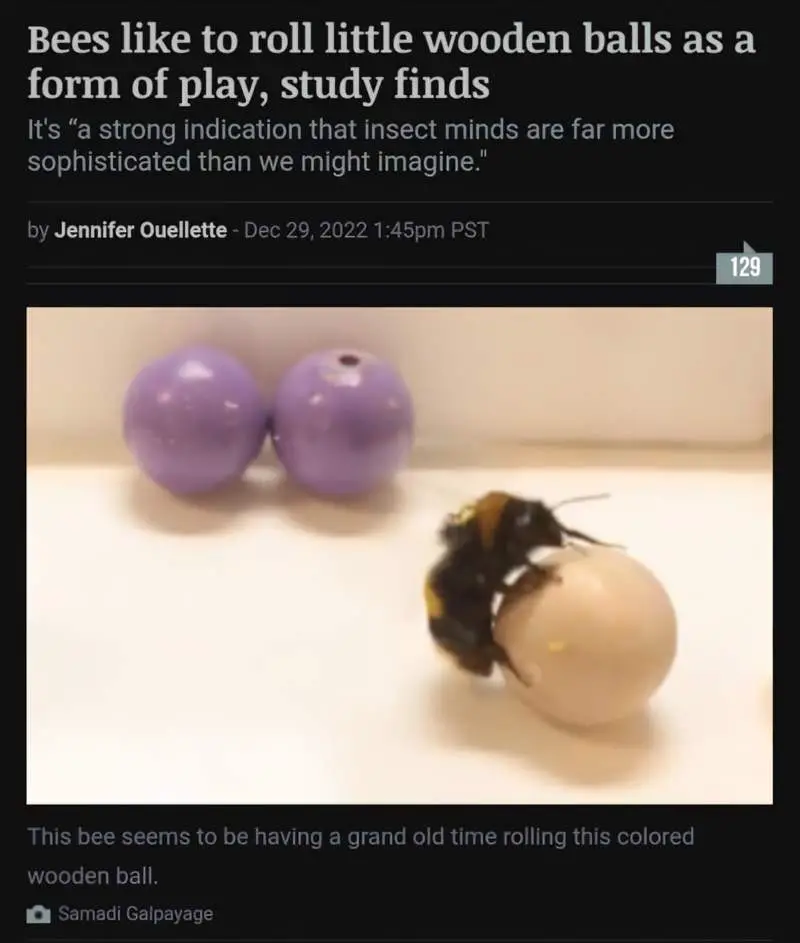

In this week’s episode of Talk Nerdy, Cara is joined by Dr. Thomas Seeley, professor of biology at Cornell University and international expert on bees. They talk about his new book, “The Lives of Bees: The Untold Story of the Honeybee in the Wild.” Topics include honeybee physiology and behavior, backyard beekeeping, and what we can learn from wild bees to improve our relationship with these fascinating creatures.

The clearing itself was pleasant if the unweeded rows of young shafts of corn were not before him. The wild bees had found the chinaberry tree by the front gate. They burrowed into the fragile clusters of lavender bloom as greedily as though there were no other flowers in the scrub; as though they had forgotten the yellow jessamine of March; the sweet bay and the magnolias ahead of them in May. It occurred to him that he might follow the swift line of flight of the black and gold bodies, and so find a bee-tree, full of amber honey. The winter’s cane syrup was gone and most of the jellies. Finding a bee-tree was nobler work than hoeing, and the corn could wait another day. The afternoon was alive with a soft stirring. It bored into him as the bees bored into the chinaberry blossoms, so that he must be gone across the clearing, through the pines and down the road to the running branch. The bee-tree might be near the water.

Second paragraph from The Yearling (1938)

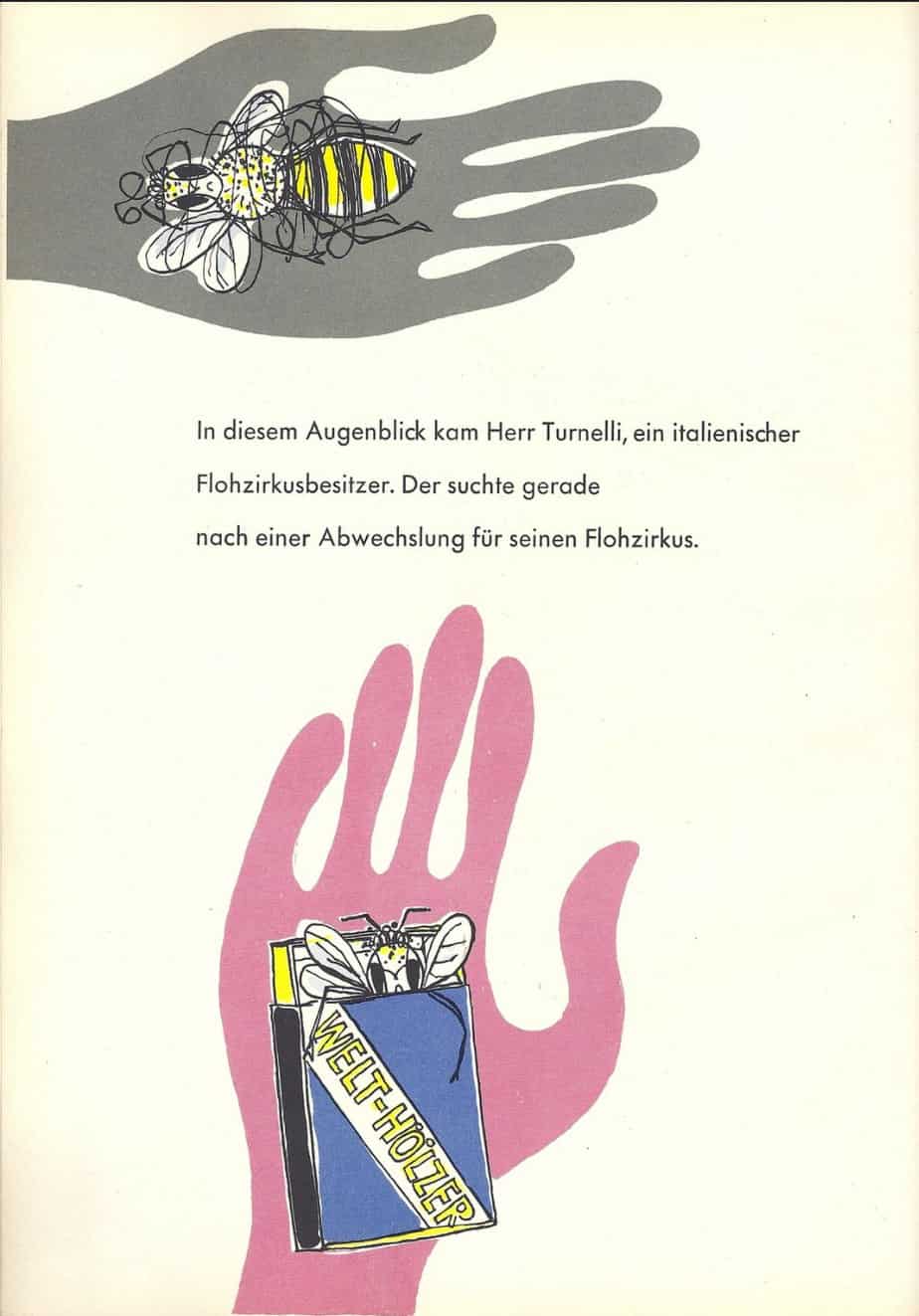

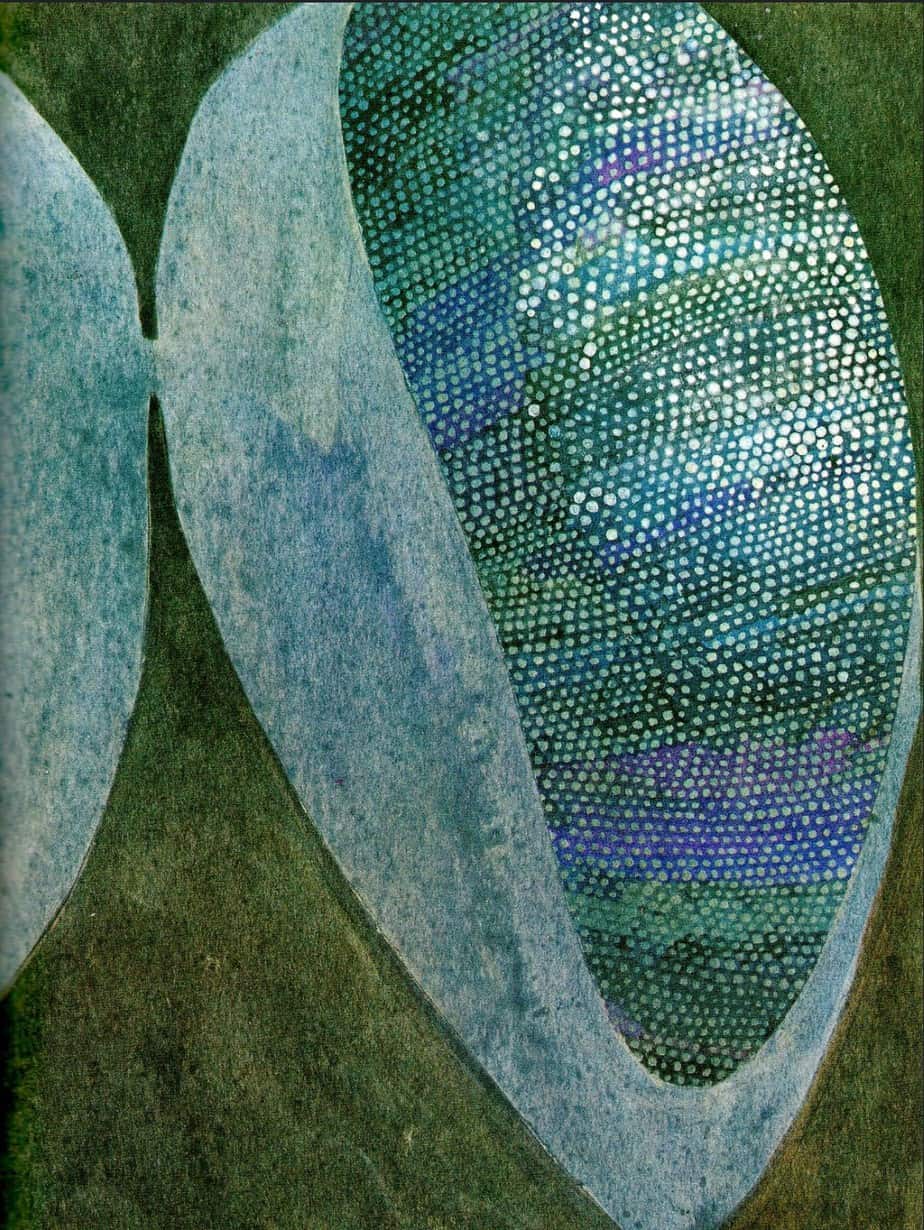

This is a rather scary looking bee. Don’t bees sting from their butt ends rather than their noses?

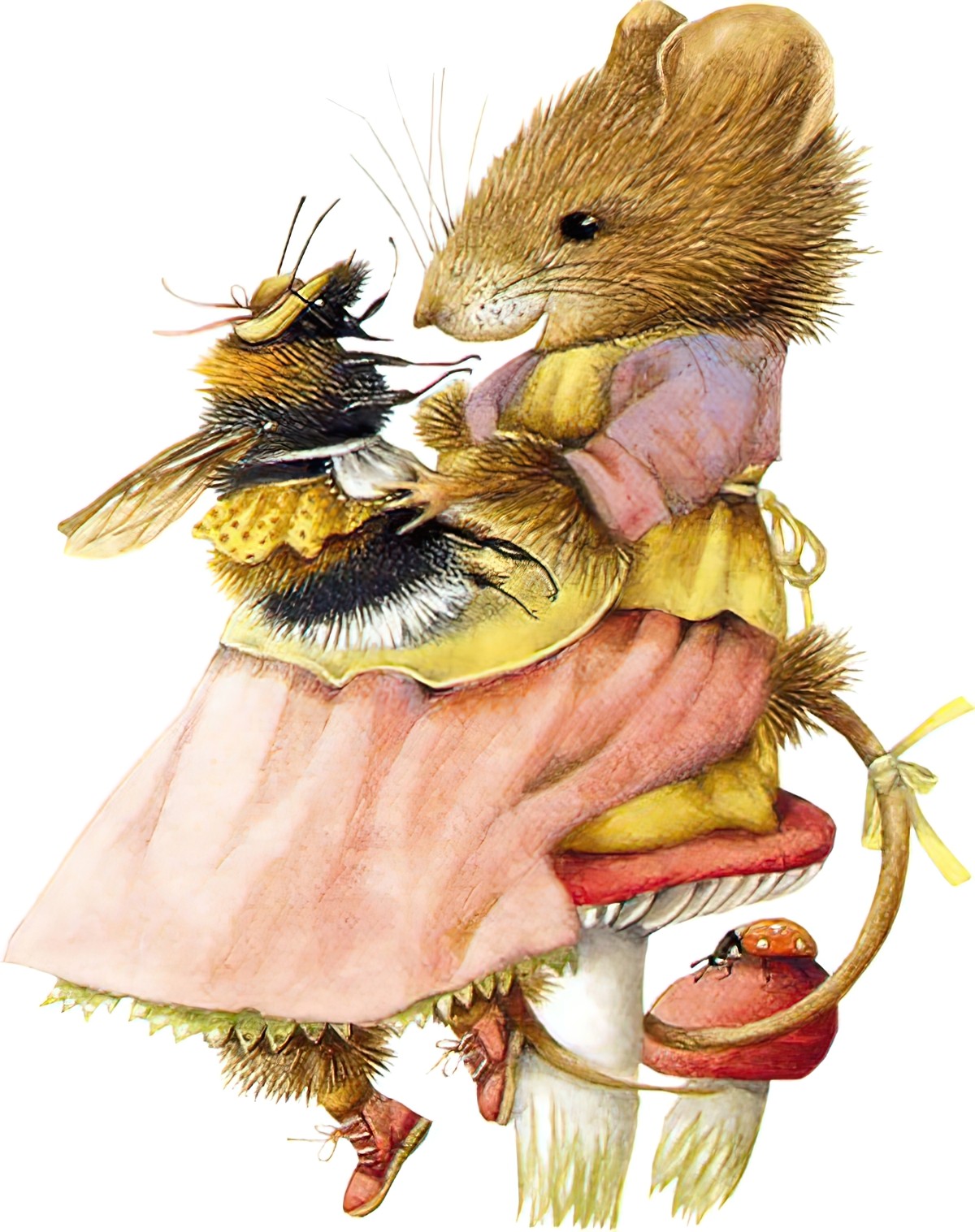

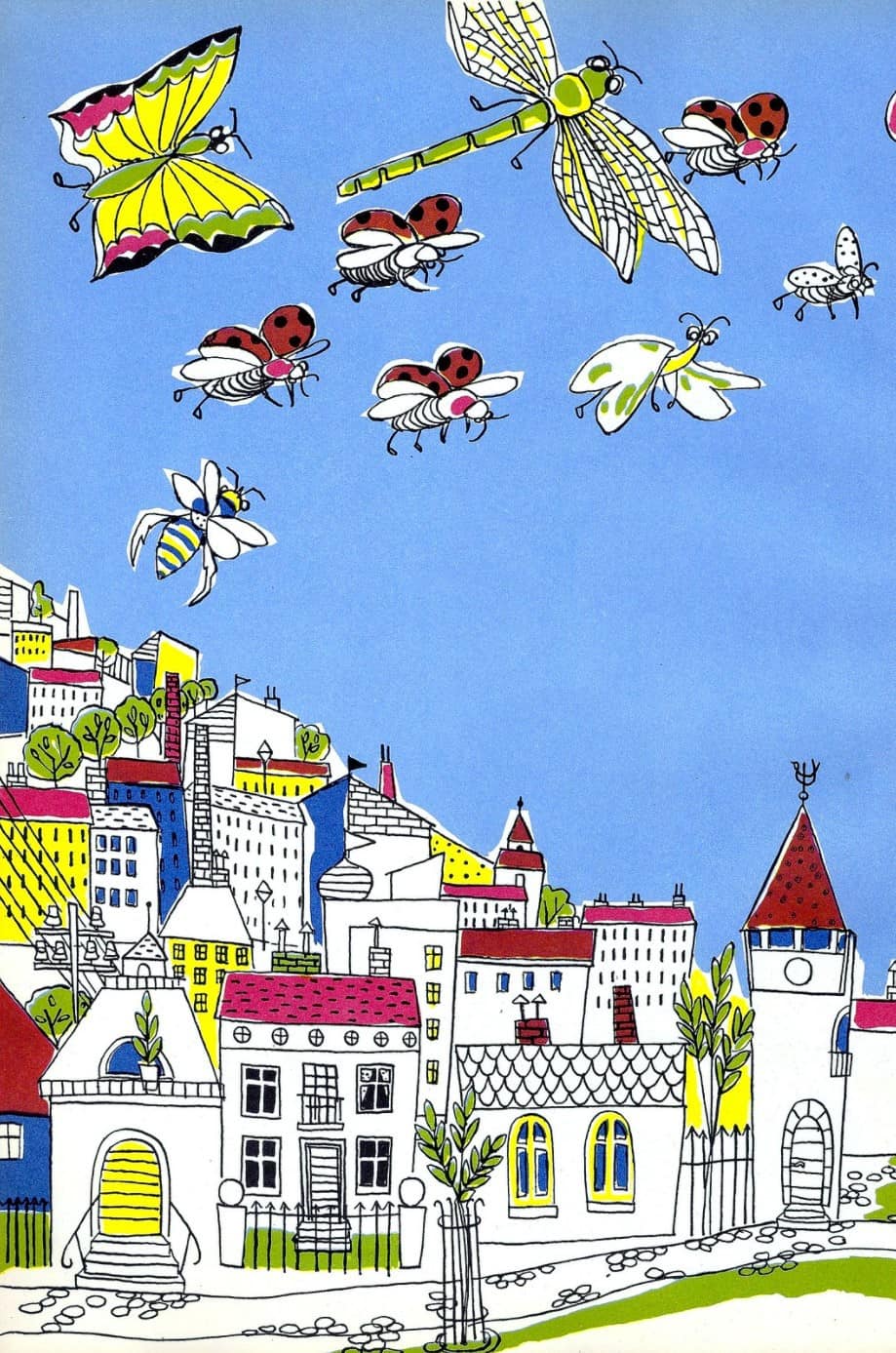

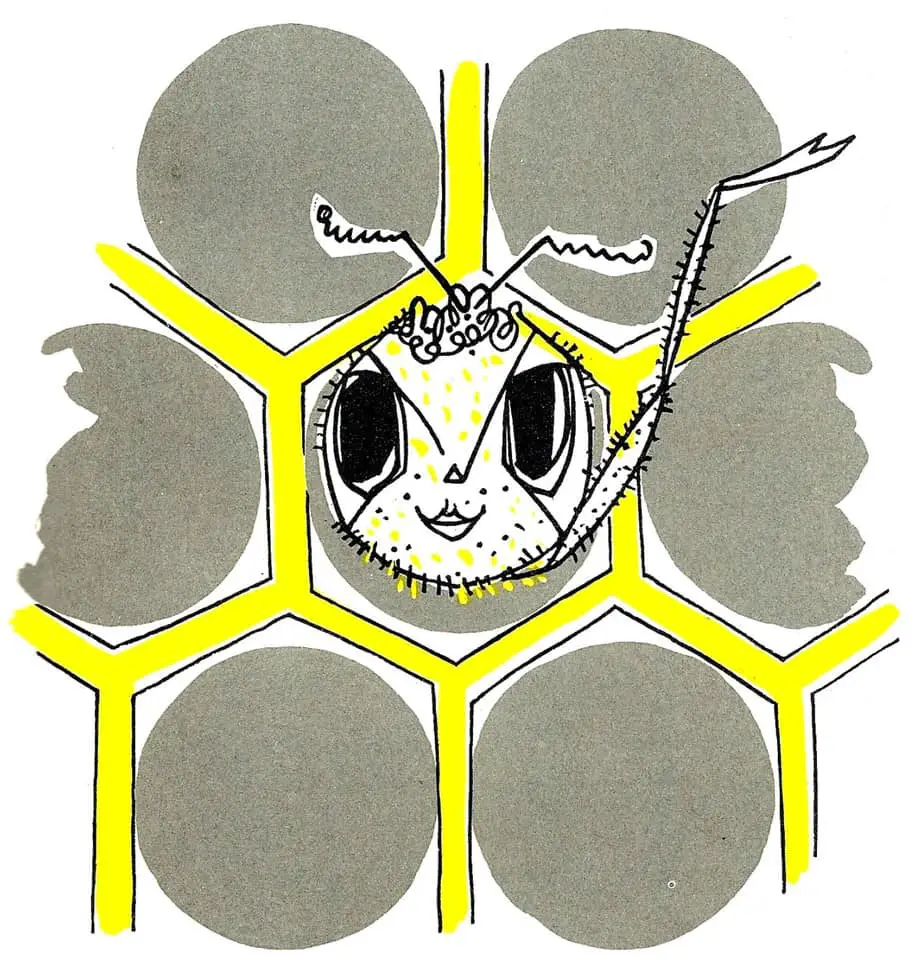

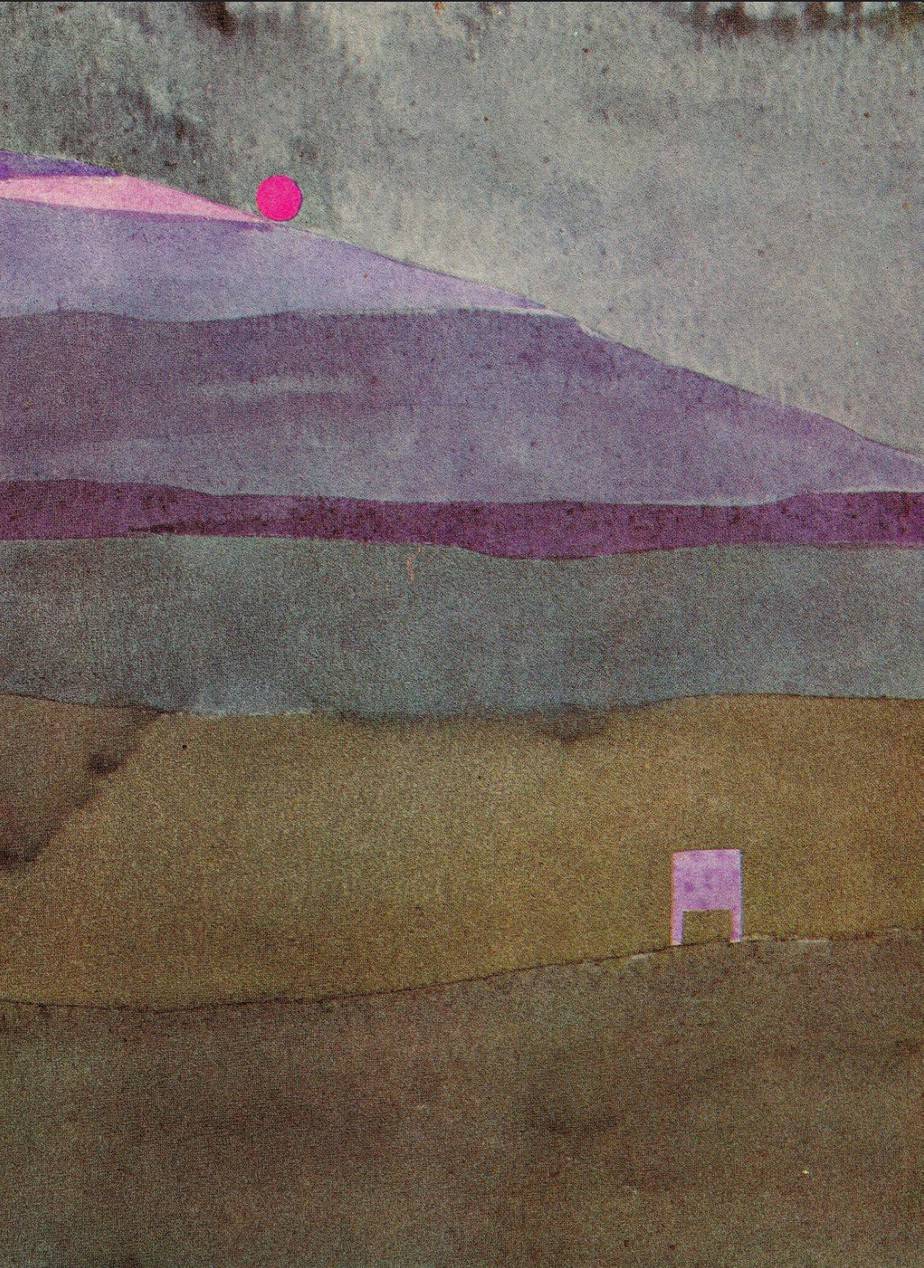

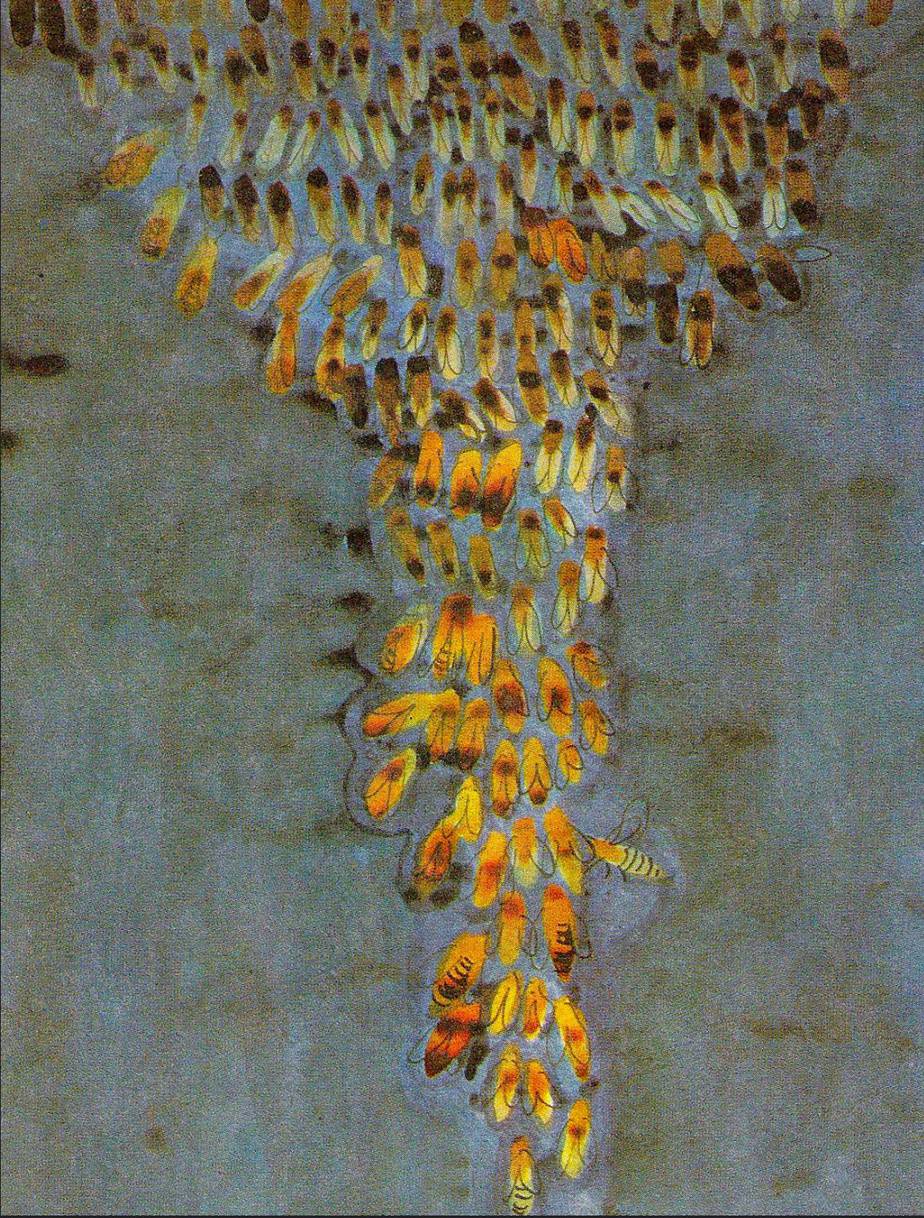

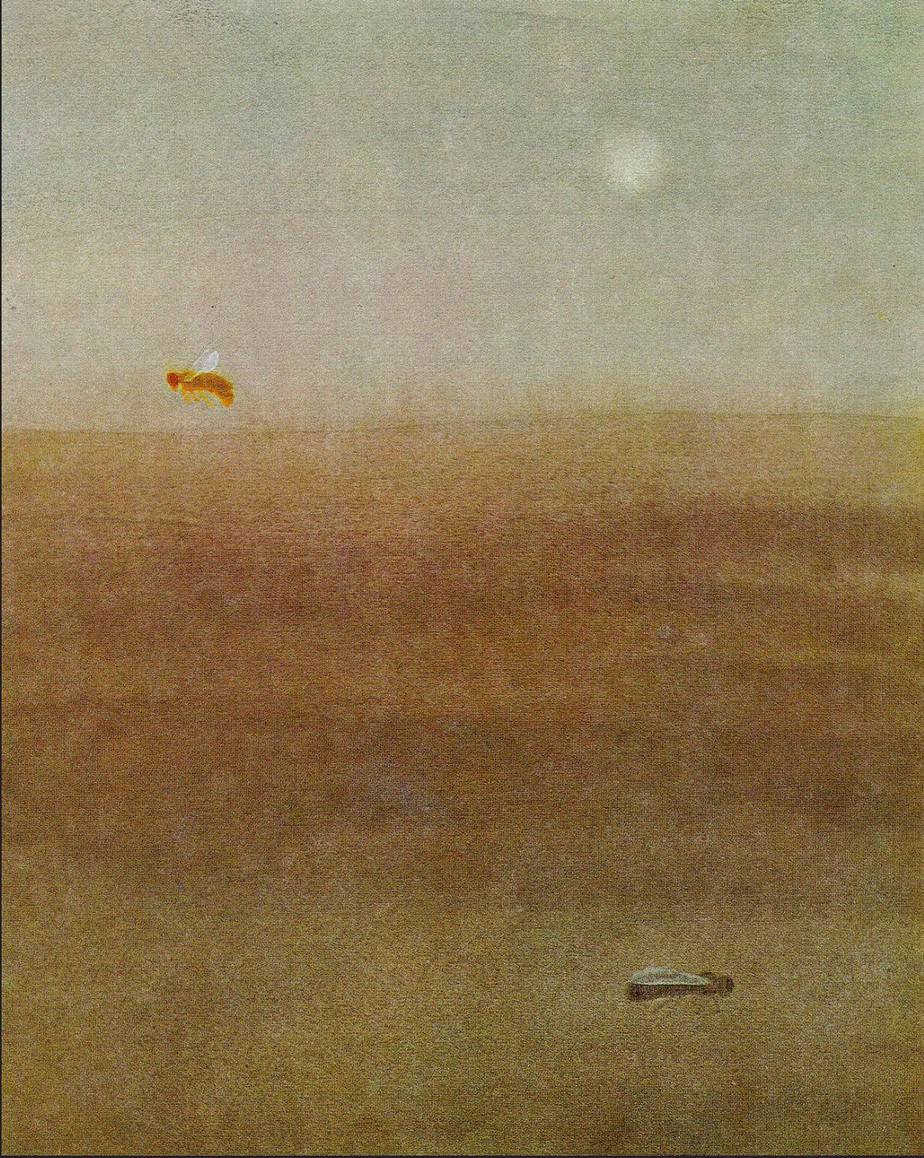

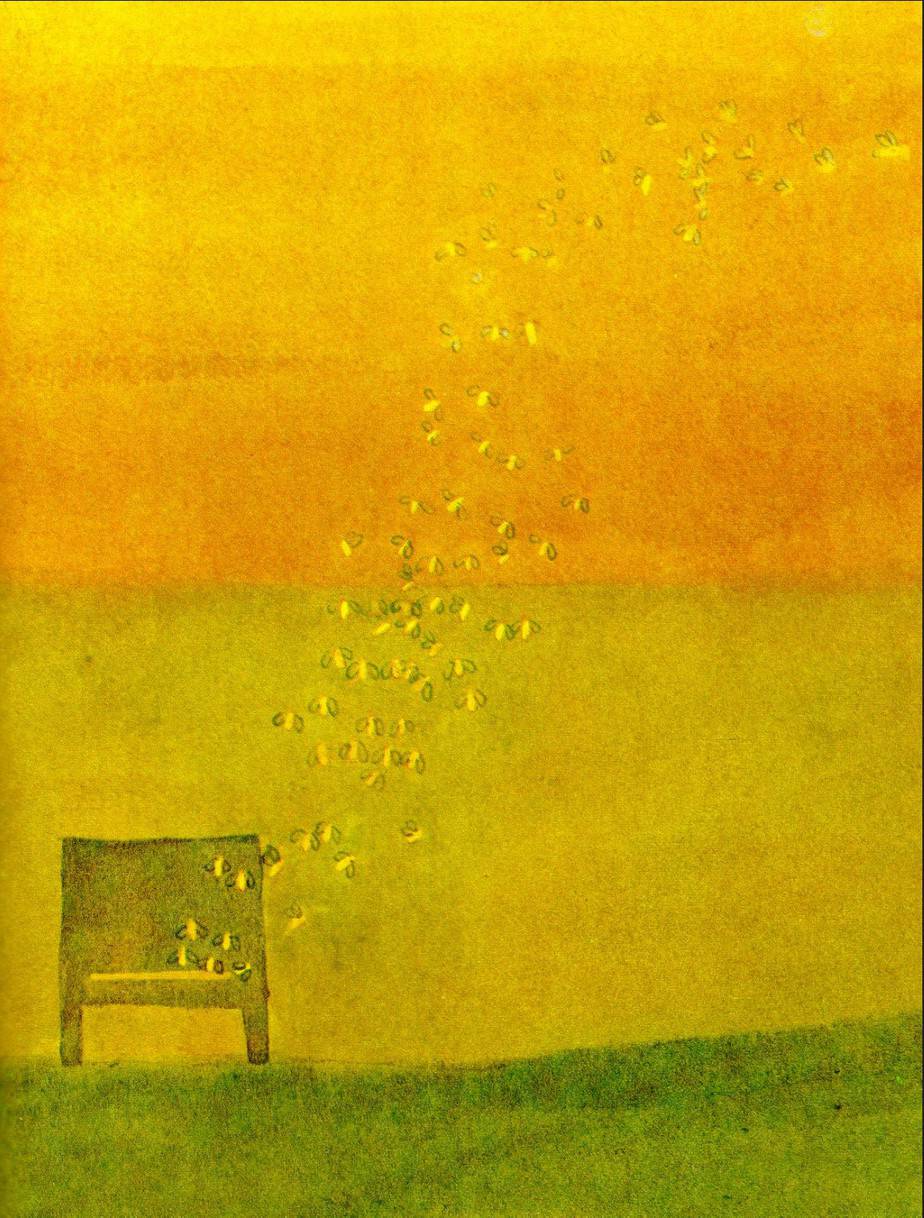

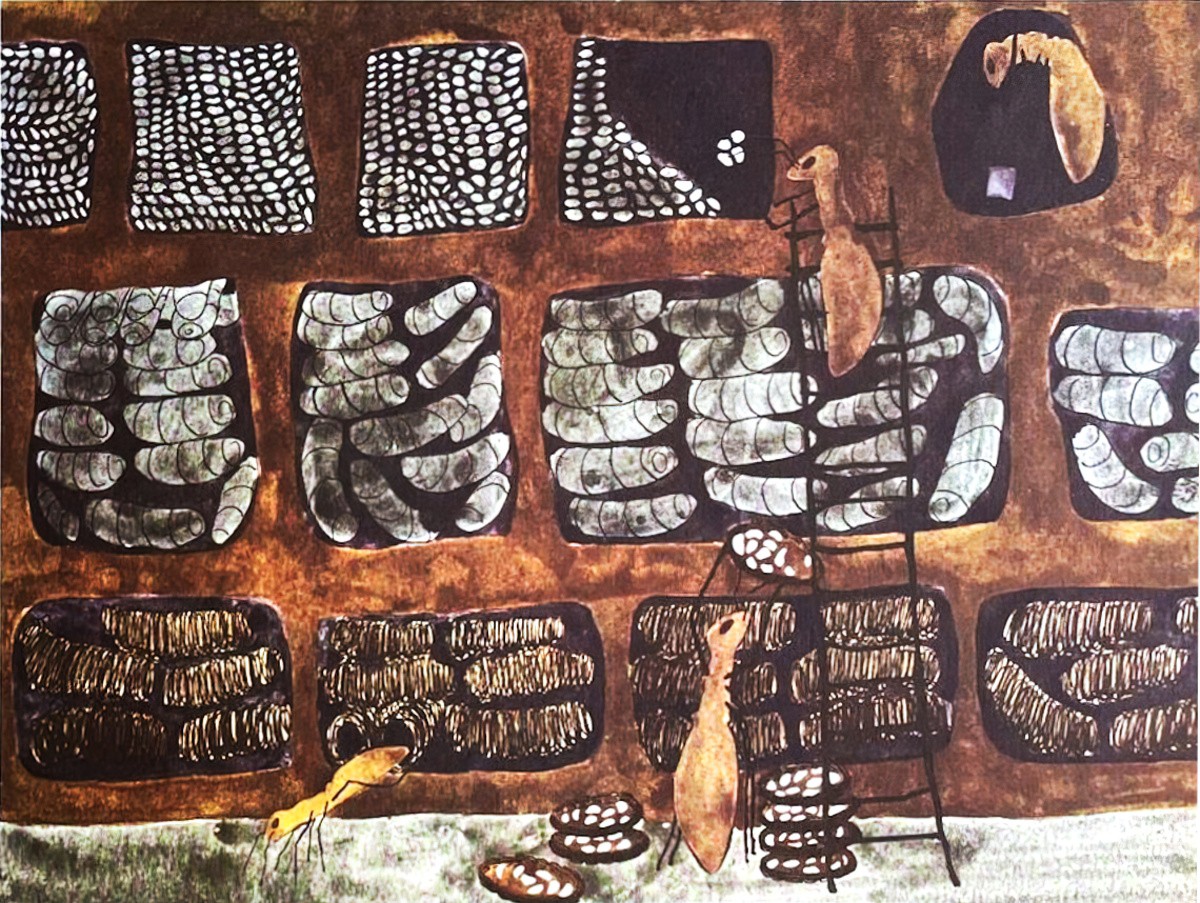

THE HONEYBEES (1967) by Colette Portal

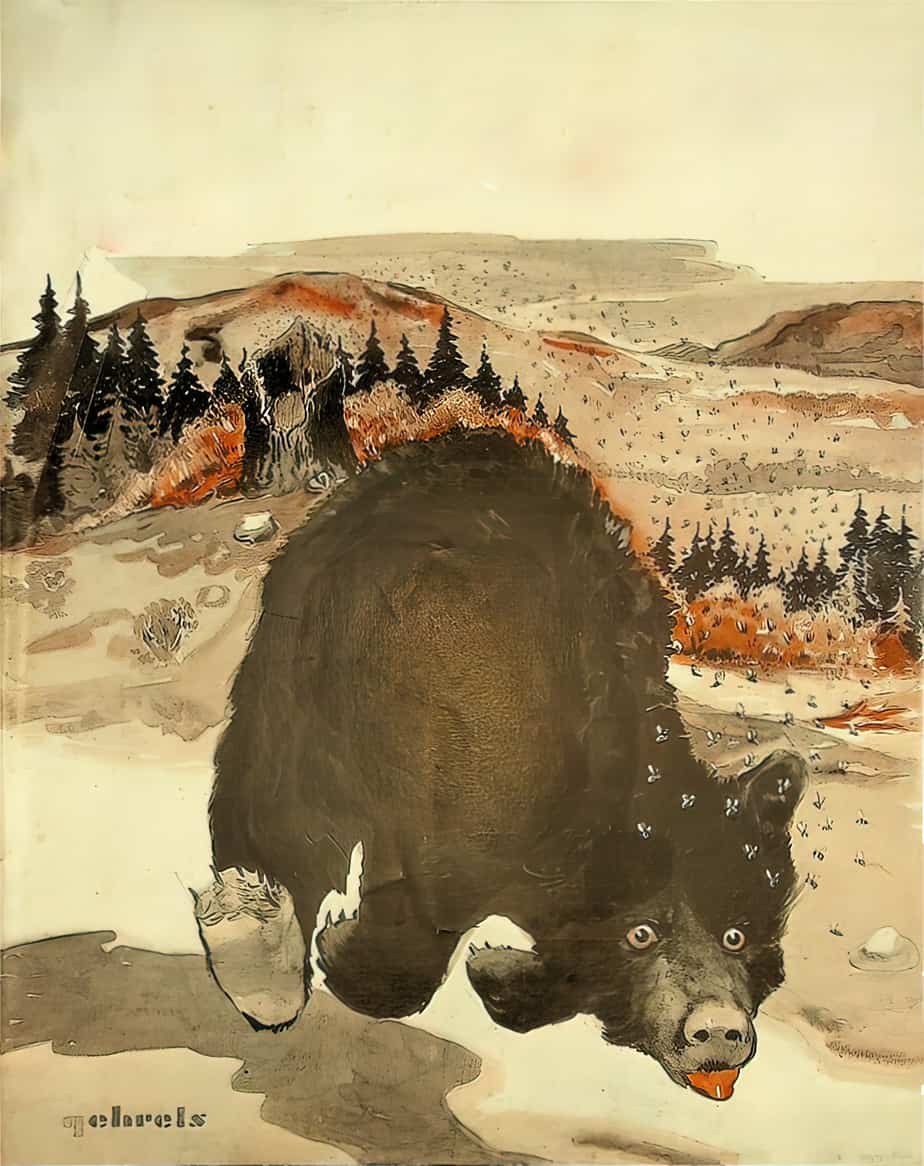

The mushroom forest came to an end. A cheerful grasshopper munched delicately at some dainty it had found—the barrel-sized young shoot of a cabbage-plant. Its hind legs were bunched beneath it in perpetual readiness for flight. A monster wasp appeared a hundred feet overhead, checked in its flight, and plunged upon the luckless banqueter.

There was a struggle, but it was brief. The grasshopper strained terribly in the grip of the wasp’s six barbed legs. The wasp’s flexible abdomen curved delicately. Its sting entered the jointed armor of its prey just beneath the head with all the deliberate precision of a surgeon’s scalpel. A ganglion lay there; the wasp-poison entered it. The grasshopper went limp. It was not dead, of course, simply paralyzed. Permanently paralyzed. The wasp preened itself, then matter-of-factly grasped its victim and flew away. The grasshopper would be incubator and food-supply for an egg to be laid.

from The Forgotten Planet at Project Gutenberg