“Beer Trip To Llandudno” is the mythic journey of a group of middle-aged men, ostensibly on an ale-tasting expedition, metaphorically on a life journey towards death. This short story is included in Barry’s Dark Lies The Island collection (2012).

Kevin Barry won The Sunday Times EFG Private Bank Short Story Award 2012 for this particular story and I’m feeling pleased with myself because I immediately spotted the genius in this one, without knowing about the award.

Here’s Kevin Barry interviewed soon after learning he’d won it.

(It’s interesting to hear Barry say that he writes 10-12 short stories a year but only one or two of those will be good enough for publication. Therefore, one collection every five years is about the right pace for a short story writer.)

Like a number of Alice Munro stories, “Beer Trip To Llandudno” involves a plot in which two characters meet after a long absence. It is a surprise to find the other has aged. There’s nothing more confronting as a reminder that you, yourself, have aged equally (or worse).

DEATH AND LITERATURE AND LIFE

A lot of stories are about death when you really drill down. (All of them?) In young adult literature, the arc is often the main character realising (psychically as well as intellectually) that they are going to die one day. Roberta Seelinger Trites has written about that, especially in relation to Heidegger’s concept of Being-toward-death.

When a story’s main characters are in their forties, they often experience a second Being-toward-death realisation. I’m in my forties myself, so I see how it happens. I lost my first friend to health reasons at the age of 40. And I was saying to a same-aged bloke the other day, things start breaking down when you’re 40. He agreed: “I’ve never been to the doctor so much I have in the past two years.” I ran this idea past my own doctor. She said, “Yes, 40 is a defining age.”

And one of the last things my 40-year-old friend posted to Facebook before he died was a meme that went something like, “Welcome to your forties. If you’ve been lucky to make it this far without anything wrong with you, just wait. You’re about to get something.” Matt died a year ago today as I write this.

I’ve so far been lucky in the health stakes — health is always a temporary state of being — but I wasn’t six months forty when I realised I can’t play tennis anymore without proper warm-ups. Learnt that the hard way. This second Being-toward-death moment reminds us that there’s nothing we can do to stave off death — death is coming for us no matter what. Life also seems to speed up around this time. (I’m told it only gets quicker.)

What would Heidegger call the middle-aged equivalent of Being-toward-death? The characters in Kevin Barry’s “Beer Trip To Llandudno” are overweight, heavy drinkers, strangers to exercise. All of that is right there on the page. By the end of the story the narrator realises he’s no longer youthful. Perhaps Heidegger would call this life stage ‘Being-significantly-closer-toward-death’, or the German equivalent thereof.

Psychologists speak of Death Anxiety. This is very different from the young adult realisation that death will come for you (eventually) because life’s possibilities have yet closed off to you. Perhaps this is that.

SETTING OF “BEER TRIP TO LLANDUDNO”

SEASON

It’s summer. The temperature doesn’t seem outlandish compared to where I live here in Australia, but it’s easy to forget that the late 30s with humidity is pretty unbearable, especially when the buildings have been built for warmth rather than for cooling.

Seasons are highly symbolic in storytelling — sometimes ironically so. Summer, in its non-ironic meaning, symbolises youth, health, vitality, the ‘best times’, where fun memories are made. These guys are out together hoping to non-ironically create their own summery excursion, making new memories, behaving like lads.

But the summer symbolism is ironic in this one. The heat is not fun but oppressive now. In contrast to the oiled limbs of the young women they see on their travels, the heat only makes their arses ‘manky’. They take off their shirts and reveal their overweight, middle-aged, beer-swilling bodies — throughout the story they are described as pigs.

On the pig theme, they stop in at some pub to rate some famously good pork scratchings. What became of those particular pigs? Pays not to think about it, but the imagery of death is right there in the (gallows) humour, and in the motif of the pig.

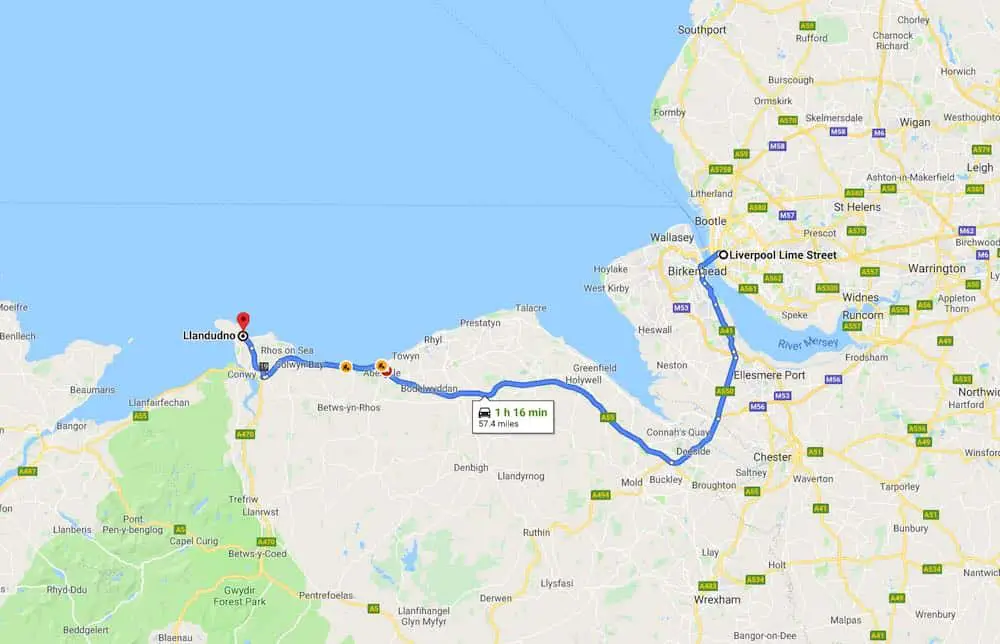

GEOGRAPHY

- Lime Street (Liverpool)

- Rhyl (mentioned)

- The Toxteth estates (skirted by the train)

- Aigburth station — ‘offered a clutch of young girls in their summer skimpies’

- Birkenhead — ‘shimmered across the water. Which wasn’t like Birkenhead.’

- Cheshire — ‘We had dark feelings about Cheshire that summer. At the North West Beer Festival, in the spring, the Cheshire crew had come over a shade cocky. Just because they were chocka with half-beam pubs in pretty villages.’

- The Marston’s

- Flint Castle — where Bolingbroke was backed into a corner

- Abergele — the men run out of beer

- Colwyn Bay

- Rhos-on-Sea

- the Penrhyn sands

- Little Ormes Head

- Llandudno (North Wales)

- The Heron Inn — an anticlimax, ‘a nice house, lately refurbished, but mostly keg rubbish on the taps

- The beach — they walk past it, thronging with youth

- Prom View Hotel — by now it is ‘dogs-dying-in-parked-cars weather’. This is where Mo meets his old flame.

- The Mangy Otter — with the good pork scratchings. The carpet has diamonds and crisps ground into it. The men decide to linger here. Big John remembers a beer from when he was sixteen years of age. This pub symbolises middle age — you start to look back on your youth and you’re afraid to go on further, for example to a pub with Crippled in the name…

- The Crippled Ox on Burton Square — ‘TV news shows sardine beaches and motorway chaos. There was an internet machine on the wall.’ (What era is this? Before smart phones, I take it — early 2000s?) They talk about how Mo has let himself go. The narrator recalls a ‘screaming barney with the missus’. Billy says they won’t be suffering from the heat much longer as there’s a change due. Thinking of hot nights, the narrator says he’s inclined to get up and watch astrophysics documentaries on BBC2 — this is him getting older and being able to take in the larger view. Mo turns up with scratch marks down his cheek.

- Henderson’s on Old Parade — the men originally plan to head here but change their minds after Mo’s reappearance.

- The train back home — Mo talks about how they ‘turn around’ and the girl is 43.

- Flint Station

- Connah’s Quay — Tom N notices new buildings since last time he passed through here. We learn that Tom N has been put on the sex offender’s register.

- Out Speke way — terrace rows with cookouts on the patios. ‘Tiny pockets of glassy laughter’ heard ‘through the open windows of the carriage. Families and what-have-you.’

- Liverpool — ‘you’re not back in the place five minutes and you go sentimental as a famine ship.’

- The Lion Tavern

- Rigby’s

- the Grapes (of Wrath)

CHARACTERS IN “BEER TRIP TO LLANDUDNO”

COMEDY

The comedy of “Beer Trip to Llandudno” derives from the futility of the mission juxtaposed with the seriousness of the characters. A similar comedic set-up can be seen in the TV series Detectorists, in which the outsider (the audience) is encouraged to laugh at characters who take metal-detecting so seriously that in-group factions develop. In “Beer Trip To Llandudno” who cares what these men think about the beer and how the rating system is set up? They do, is all.

Stories about in-groups with shared hobbies have a few things in common:

- The main characters care A LOT about their passion

- The passions are esoteric. (I’m put in mind of The Dull Men’s Club).

- These stories tend to star men who will never be alpha males, so they get together to be the alphas of their own, separate worlds.

- Everyone else in the setting cares not a jot.

- A few of the opponents are actively dismissive. Often those dismissive characters will be women and girls. (In Detectorists, one of the characters observes that women seem to be immune to obsessions. I disagree, but that does describe the stereotype expressed across the oeuvre of these stories.)

- The male main characters are often blatantly sexist. They can’t be alpha men, but at least they’re not women. Asexual archetypes are also pretty common.

- It’s true that most comedies involve an element of ‘niche passion’. The characters in The I.T. Crowd, for instance, have highly specialised knowledge of computers. Joey from Friends has a thing about sandwiches. Kramer from Seinfeld seems to have developed a new obsession every episode (soup, fruit, etc.).

- The main characters of these stories must know a lot about their subject matter, which means a tonne of research by the writer. These characters often know little about anything else, and lead chaotic lives.

- On screen the roles will be played by ‘character actors’ (or the literary equivalent). No leading men here. They have little social capital outside their own limited subculture.

- If they lose their subculture of friends they are left with very little. Remaining part of the gang is everything. Exclusion is a type of death. (That happens in this story.)

- Within the subculture there will be constant jostling for hierarchy. This serves to show the audience that the human wish for power and social capital is a part of the human condition, and happens at every level. These stories remind us that whatever power big struggle we are involved in, it looks ridiculous to anyone with a wider, birds’ eye view. Such comedies lend themselves well to dark commentary on death, because the audience asks, What am I doing with my life? Are my daily interpersonal big struggles life and death matters?

FAMILIAL RELATIONSHIPS

As mentioned in the interview above, others have pointed out that each of the men fulfils a role within the ‘family’ of friends. ‘We were family to Mo when he was up at the Royal…’

The Members Of Real Ale Club, Merseyside Branch

One thing that connects them is that they don’t approve of lagers, or of anyone who drinks them.

Narrator

Well-prepared and knows what’s what with his Illustrated Guide to Britain’s Coast

Mo

The child, asking questions about the route (rather than looking it up himself); interested in the roller coasters and water skiing. Down a testicle since spring (emasculating him)

Tom Neresford

Stomach troubles. Has never been far. Has been put on the sex offenders’ register. (I’m inclined to think this was for a good reason, unlike the interpretation of his mates, who prefer to think of it as a miscarriage of justice.)

Everett Bell

‘wasn’t inclined to take the happy view of things’. Knows a lot e.g. about history and Shakespeare. “My brother got the house, my sister got the money, I got the manic depression.” ‘Half mad’

Billy Stroud

‘the ex-Marxist’, ‘involved with his timetables’, has an earpiece in, listening for the news and the weather. He is the organiser, and therefore I take it he’s the ‘mother’ of the group. Cemented when he says that cold stuff makes you hotter overall because it makes the body work harder — he seems to be the one organising the food as well as any logistics. However, he is also described as ‘innocent’. Perhaps he is one of the children?

John Mosely / Big John

‘if there was a dad figure among us it was Big John with his know it all interruptions’. Decides when it’s time for the group to move on. Jobless for the past 18 months.

STORY STRUCTURE OF “BEER TRIP TO LLANDUDNO”

“Beer Trip To Llandudno” is your classic mythic journey. In story, train trips are often symbolic of the one-way ticket through life. Typical of a road trip journey, the characters in “Beer Trip To Llandudno” (chosen family) jockey for position with their own minor conflicts, but meet true opponents along the way. By the end of the story the main character will have come to some realisation, and home will never be the same again. In this case, our ‘main character’ is the first person narrator.

PARATEXT

My wife and I were living in Liverpool at the time and the heating in our flat was really terrible. So we had no option but to go to a pub across the road called The Lion Tavern of an evening—just to keep warm, you understand. It was a real ale pub and the local branch of CAMRA [the Campaign for Real Ale] was often in there. And one night I went up to the bar and there was a newsletter about recent outings by this group of ale enthusiasts and I just thought, “Fucking gift,” you know? A beer club’s outing gives the perfect shape for a story.

Interview with Kevin Barry at The Paris Review

SHORTCOMING

The narrator is on a ‘fun’ trip but doesn’t yet realise he’s too old to really enjoy it. The heat is going to really get to him. He’s going to be maudlin, and not just because of the beer.

DESIRE

He wants to have a good time like a young man out with the lads. He wants to remind himself that he is young and full of life.

OPPONENT

The companions are allies for the main part, but there’s niche in-fighting regarding his dual roles on the committee.

The main opposition comes from the people they meet who remind the men that they are no longer young.

Mo’s old-flame Barbara is the stand-out opposition, therefore, because she has aged. ‘A lively blonde, familiar with her forties but nicely preserved, bounced through from reception.’ Notice how the men notice her age. The narrator says ‘but’ instead of ‘and’ in that sentence. It’s easy to see how a woman has aged; not so easy to turn the mirror back on yourself if you’re a man. (When asked, women tend to say we begin to feel old at age 29; for men it is 58.)

The young women also remind these men that they are old. They admire the girls’ bodies knowing they can’t have them. (Although perhaps one of them hasn’t realised that — which might explain why he’s on the sex offender’s list.)

PLAN

The men have planned a journey through Welsh pubs. Their task is to rate beer and snacks.

BIG STRUGGLE

The running argument (comedic for its triviality) is that the narrator should not be holding two positions in Ale Club, outings and publications. Finally he steps down from writing the newsletter. We know this is the main Battle scene because it directly precedes his Anagnorisis. He has lost the big struggle to keep both roles and ends up getting rid of them both.

ANAGNORISIS

First I want to talk about Kevin Barry’s preferred narration in relation to the various Anagnorisis experienced by his storyteller narrators.

The first person voices in a Kevin Barry story are so realistic I have to remind myself it’s not the author narrating — it’s an invented character. Generally, these narrators are able to step back and view their own intradiegetic selves as comedic characters, along with the rest of the crew. This particular narrator fits that description. How is he able to step outside himself? Because he’s gained enough perspective over the course of this particular story that he is able to see himself as a flawed individual.

Sometimes one of the more difficult decisions when writing our own short stories is choosing the style of narration. First person? Third person (close)? Third person (distant)? If, like Kevin Barry, you want your main character to have stepped back and seen the comedic, human side of themselves by the end of the story, this first person narration works well.

Of course, this particular Anagnorisis is all connected to the realisation that he’s not young anymore, but I went into that up top.

What does the narrator do, which tells us, the reader, he has achieved that particular realisation? Well, he steps down from his role as newsletter writer. He can’t face writing any more obituaries.

In short, the narrator has developed Existential* Death Anxiety over the course of one day out with the ‘boys’. In order to reach this point, it is said you need the following three things, and since the brain is still developing until about age 25-30, these milestones generally only come with middle age:

- a full awareness of the distinction between self and others

- a full sense of personal identity

- the ability to anticipate the future

*Existentialism: an outlook which begins with a disoriented individual facing a confused world that they can’t accept. Existentialism’s negative side emphasizes life’s meaningless and human alienation. Think: nothingness, sickness, loneliness, nausea.

NEW SITUATION

By stepping down as the writer of obituaries, sometimes of very young men (around the same age as these characters), the narrator is turning away from death. And for now, that is how he will cope with it.

This is the difference between the 40s and the 80s — not many octogenarians are able to turn away from their own impending deaths — they’ll have lost too many peers. Their own health has deteriorated and they feel it keenly. A story about 80 year olds would feel quite different from this one.

FURTHER READING

Social spaces and non-places: The community role of the traditional British pub

Reid Allen, 6th December 2022

(Yes, Wales is a part of Great Britain.)