Lectrology, the study of the bed and its surroundings, can be extremely useful and tell you a great deal about the owner, even if it’s only that they are a very knowing and savvy installations artist.

Terry Pratchett, Unseen Academicals

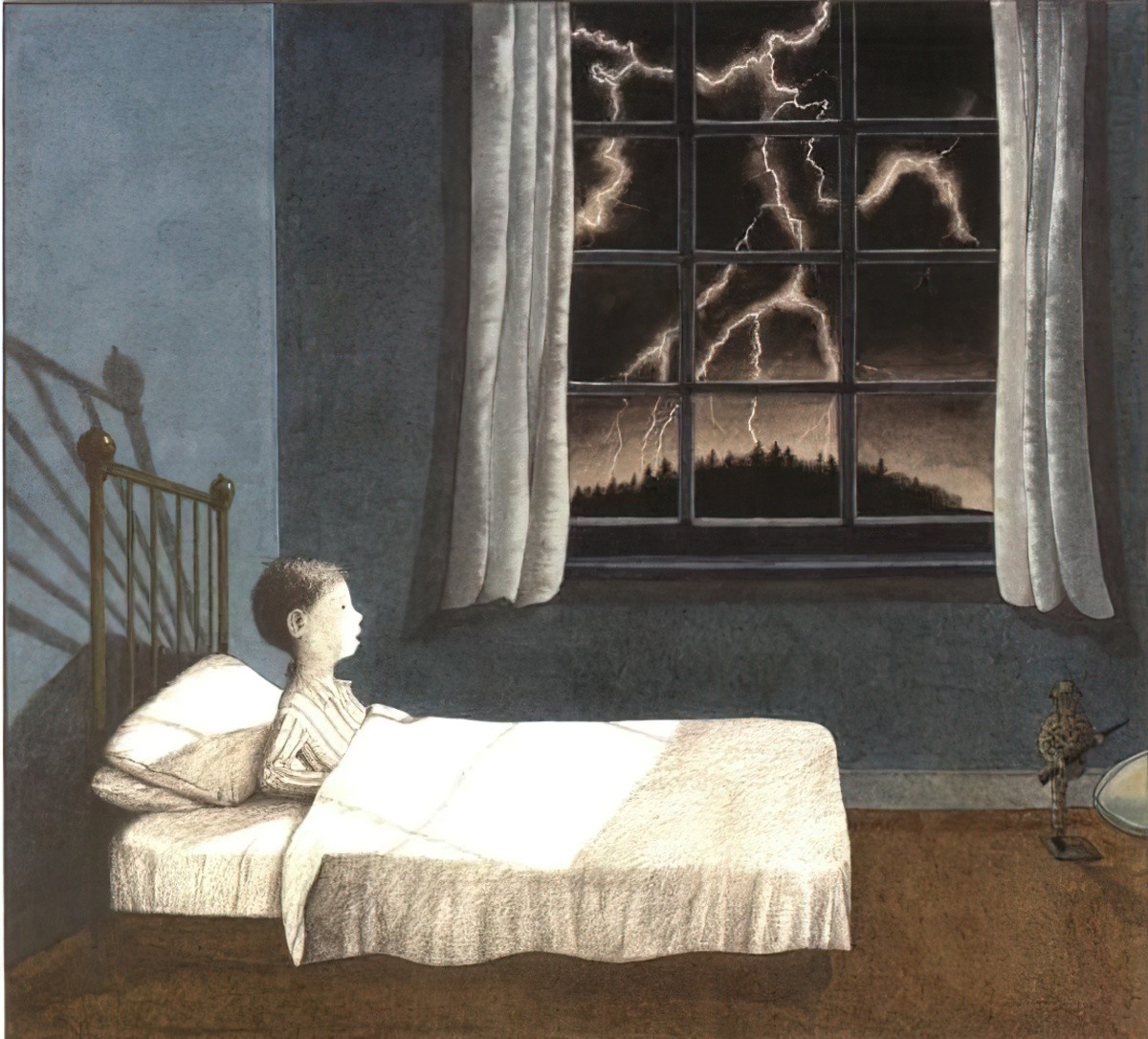

A character’s room can contribute to characterisation… Setting is frequently used to symbolize the character’s moods as well as power position. The bright sunny morning in the beginning of Anne of Green Gables corresponds to her hopeful expectations. A change of setting can parallel the change in the character’s frame of mind. A storm can symbolize the turmoil in the character’s psyche.

The Rhetoric of Character In Children’s Literature, Maria Nikolajeva

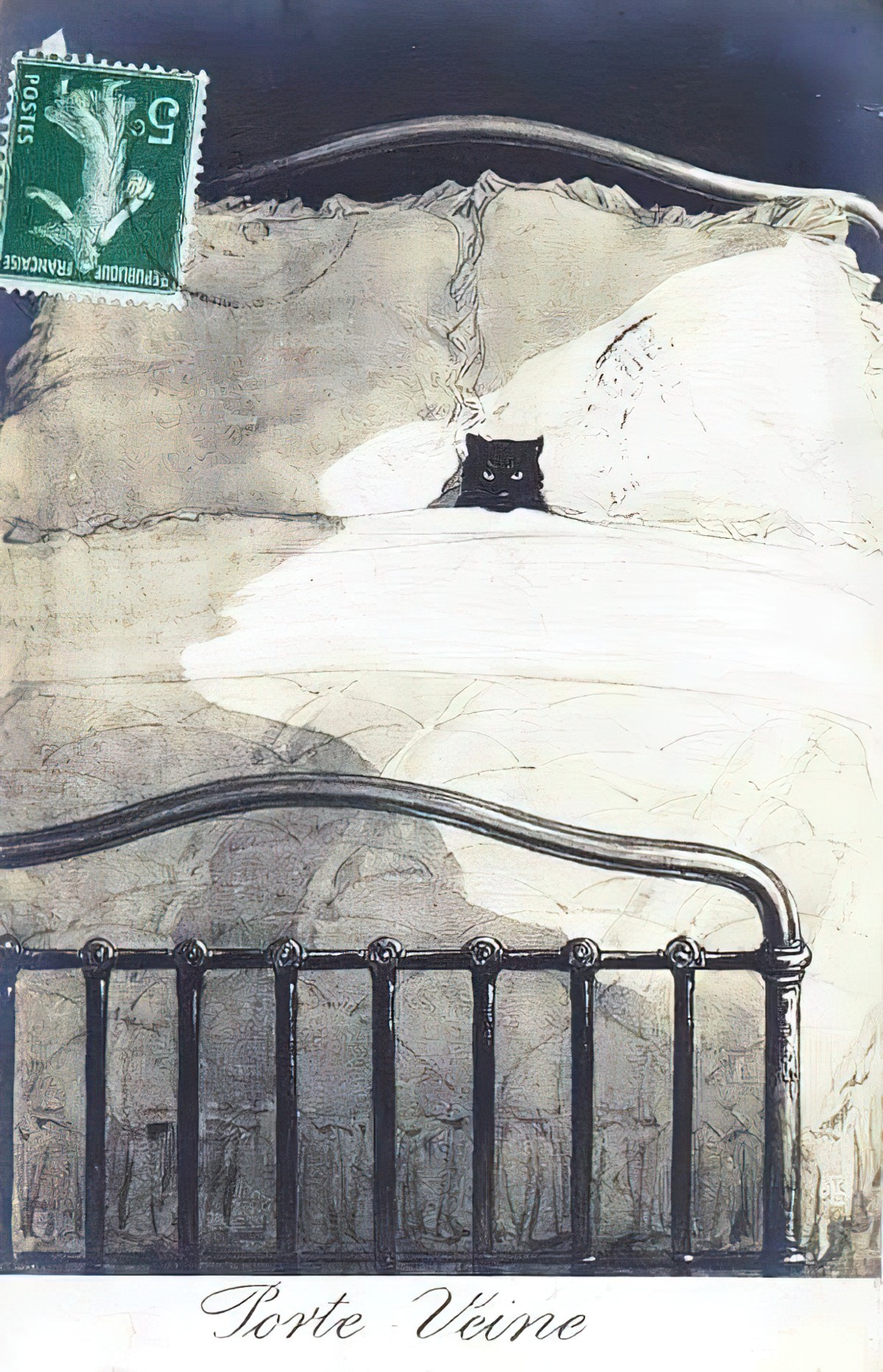

Each of us has three lives: public, private and secret. We are rarely afforded glimpses into the bedrooms of other people, a room which, in the West, bridges the private and secret selves.

CANOPY BEDS

Canopy beds can be cosy, or anything but.

But fiction lets us all the way in. In fiction, the bedroom can be a representation — perhaps ironic — of a character’s inner world.

EXAMPLE ONE: THE SPARTAN BEDROOM

Alice Munro is master at describing the ordinary, and so she shows us here, in her descriptions of bedrooms described as ‘Spartan’ or as bachelor pads.

My father slept in what had been a pantry, off the kitchen. He had an iron bed and a broken-backed chair he kept his stack of old National Geographics on, to read when he couldn’t sleep. He turned the ceiling light off and on by a cord tied to the bed-frame. This whole arrangement seemed to me quite natural and proper for the man of the house, the father. He should sleep like a sentry with a coarse blanket for cover and an unhousebroken smell about him, of engines and tobacco. Reading and wakeful till all hours and alert all through his sleep.

Alice Munro, “Queenie“

The ceiling of [Delphine’s] room sloped steeply on either side of a dormer window. There was a single bed, a sink, a chair, a bureau. On the chair a hot plate with a kettle on it. On the bureau a crowded array of makeup, combs and pills, a tin of teabags and a tin of hot chocolate powder. The bedspread was of thin tan-and-white striped seersucker, like the ones on the guest beds.

Alice Munro, “Trespasses“

He stood aside for Robin to enter the big front room, which had no rug on the wide painted floorboards and no curtains, only shades, on the windows. There was a hi-fi system taking up a good deal of space along one wall, and a sofa along the wall opposite, of the sort that would pull out to make a bed. A couple of canvas chairs, and a bookcase with books on one shelf and magazines on the others, tidily stacked. No pictures or cushions or ornaments in sight. A bachelor’s room, with everything deliberate and necessary and proclaiming a certain austere satisfaction. Very different from the only other bachelor premises Robin was familiar with—Willard Grieg’s, which seemed more like a forlorn encampment established casually in the middle of his dead parents’ furniture.

Alice Munro, “Tricks“

The room was almost square, perhaps a little longer than it was wide, with only one window that filled almost the entire far wall. So far, completely blank and empty, it was expectant, almost curious, and Natalie, standing timidly just inside the door, in the walls opposite the window, looked at the bare walls with joy; it was, precisely, a new start.

Shirley Jackson, “Hangsaman”

ANALYSIS

Square, one windowed, blank and empty, Natalie’s space is not quite the lavish palace setting one might hope for in a new start. Yet, this clinical style space is perfect for the girl “standing timidly” right at the threshold. Natalie’s apprehensive joy is mirrored in the room, personified in its “expectant, almost curious” reaction to its new owner. The space’s barrenness can be filled with Natalie’s belongings, thoughts, and feelings.

Repeatedly, Natalie’s “joy” comes from staring at the bare walls, and a projected potential. Newness creates safety. Though the walls are tan, the ceiling decorated “in the proper institutional bad taste, so uninspired as to be almost colorless, and the dark-brown woodwork and the smallness of the room made it seem cell-like and dismal” with one single bulb hanging over Natalie’s head, her impression is of comfort.

Though the “bad taste” and “uninspired” decor should be confining and “dismal,” Natalie’s first gaze into the room leaves her feeling satisfied and content. Her new space gives the impression of “setting her in a sort of package, compact and square and air and water-proof, a precise, unadulterated, fresh start…a new clean box to live in”.

This insular, sectioned off aesthetic equivalent of a jail cell instills contentment in entrapment. Natalie’s previous life in her stifled suburban space becomes a distanced version of her self (and, by extension, trauma) escaped through creating a sense of new and explorable setting.

The other side to Natalie’s expectations is a sense of dread that the room enforces. Not only does Natalie have her ideas for the room, but it is as if the room has always been waiting for her entry.

Its personified expectancy and curiosity lead into its “setting her in a sort of package,” coming alive to meet its new occupant. The room is as sentient as its new owner. […]

The struggle between what belongs in and out manifests in Jackson’s attention to smalL architectural symbols. Doors are a means to access the space in between, a threshold that creates the eerie connection between reality and non reality.

“Homespun” Horror: Shirley Jackson’s Domestic Doubling by Hannah Phillips

EXAMPLE TWO: THE TECHNICOLOUR BEDROOM

She woke in the night with the vibrating pink lights of the restaurant sign across the street flashing through her window, illuminating the other teacher’s Mexican doodads. Pots of cacti, dangling cat’s eyes, blankets with stripes the color of dried blood. All that drunken insight, that exhilaration, cast out of her like vomit. Aside from that, she was not hungover. She could wallow in lakes of alcohol, it seemed, and wake up dry as cardboard, flattened. Her life gone. A commonplace calamity. The truth was that she was still drunk, though feeling dead sober.

Alice Munro, “Fiction“

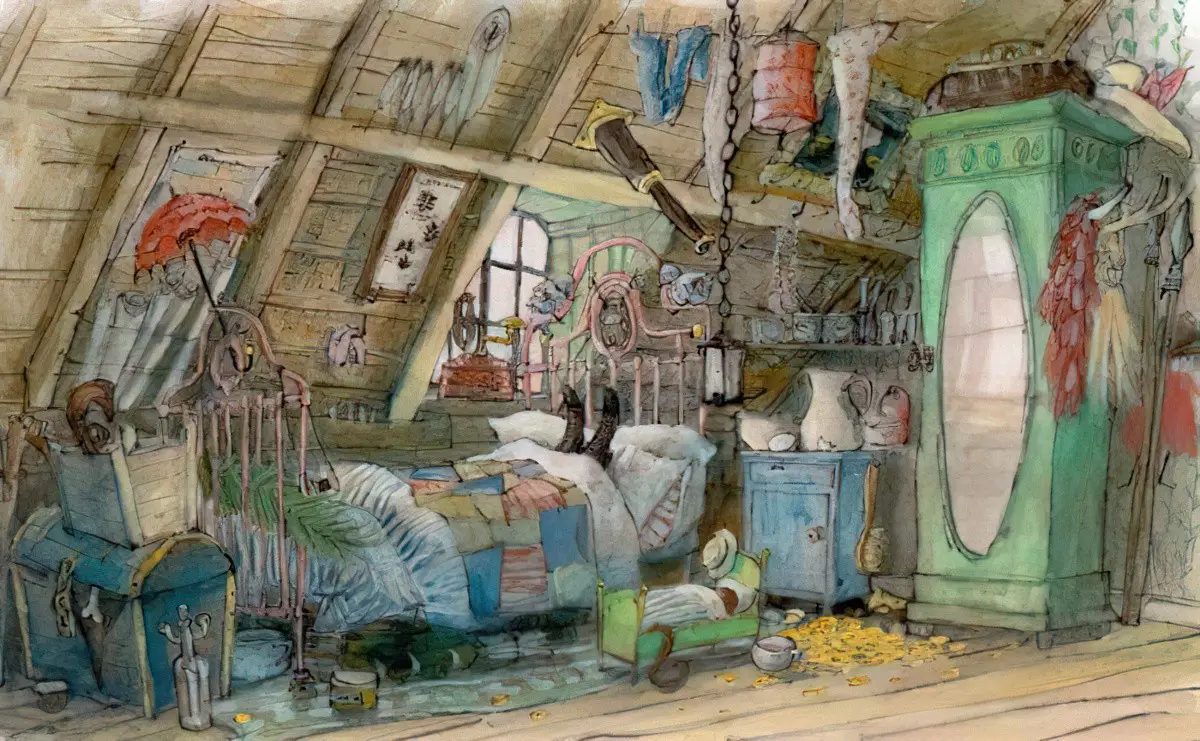

EXAMPLE THREE: THE ATTIC BEDROOM

Upstairs in her strange little room Harry dropped her pack on the floor, pleased to be up there, still hearing family voices but not having to answer them. Though the attic was called Harry’s room, it as not really a room at all, simply a floor laid over the ceiling joists and insultation, a space fitted in under the pointed “A” of the roof. Its dormer window looked out to sea across curved wands of bougainvillaea, and she shared the space with boxes of Christmas decorations. A little mirror without a frame hung on a nail in one of the diagonals that supported the iron roof. She could see tents, ground sheets, rolls of wallpaper left over from previous home improvements, and many other spare things that just might be needed some day. Here at night, over many years, the house had groaned and murmured to her…

The Tricksters by Margaret Mahy

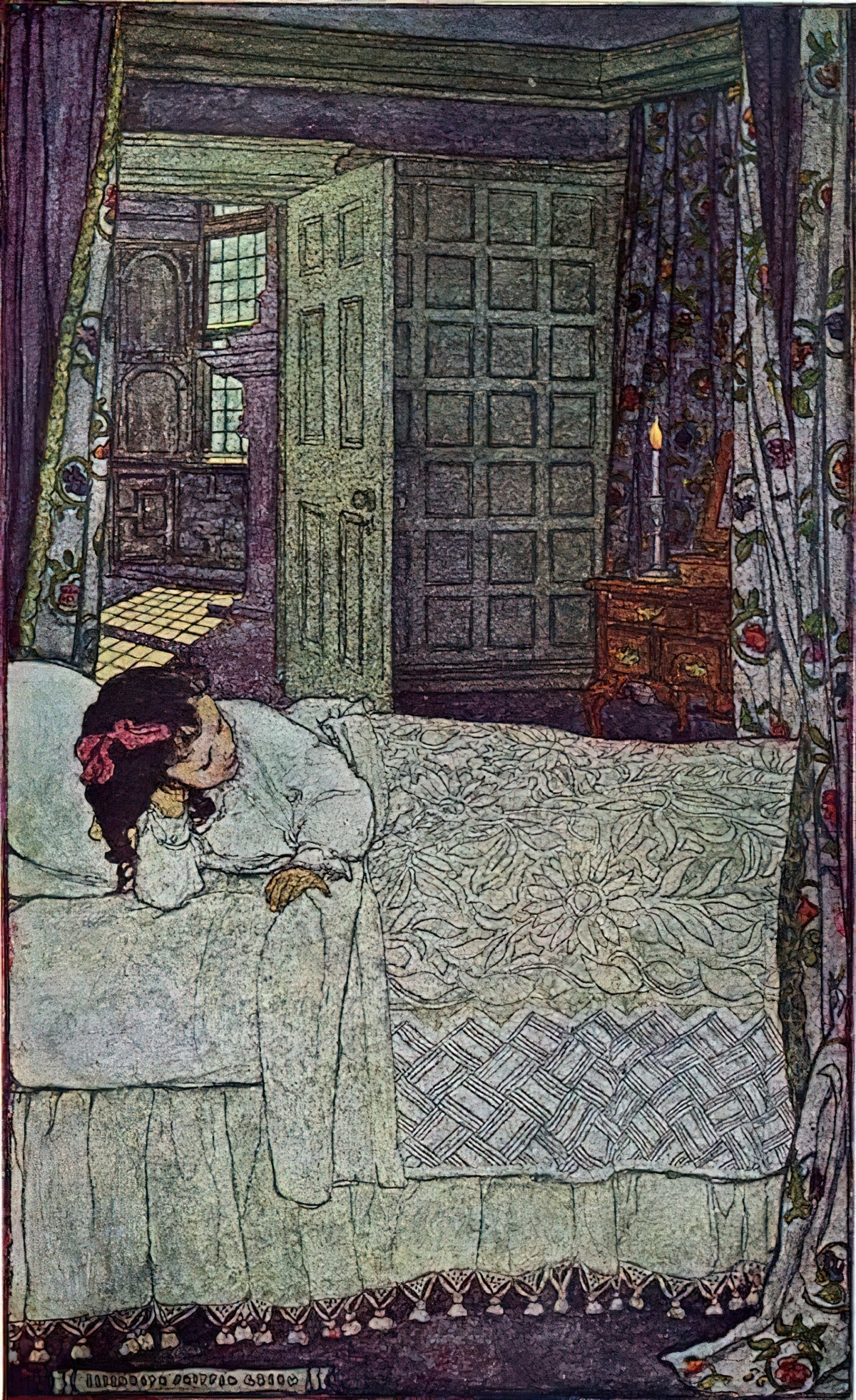

EXAMPLE FOUR: THE FOREST BEDROOM

The forest is symbolically rich for storytellers, multivalent in its associations — a place of refuge and a place of terror at once. The forest is basically the subconscious. That is how it functions in fairytale.

The bedroom from Beauty and the Beast (1945) is interesting because Beauty’s bedroom spills over into the forest. This is a story which delves into the deep subconscious. (The text below has been auto translated from French.) For ane xample of forest as bedroom in Sleeping Beauty see 12 Films Inspired by the Art of Gustave Doré.

The bedroom without walls, blending with surrounding landscape has been utilised by contemporary picture book illustrators, for instance Anthony Browne in Just A Dream. (In that post I offer other examples.) There’s A Sea In My Bedroom by Margaret Wild blends a child’s bedroom with the sea.

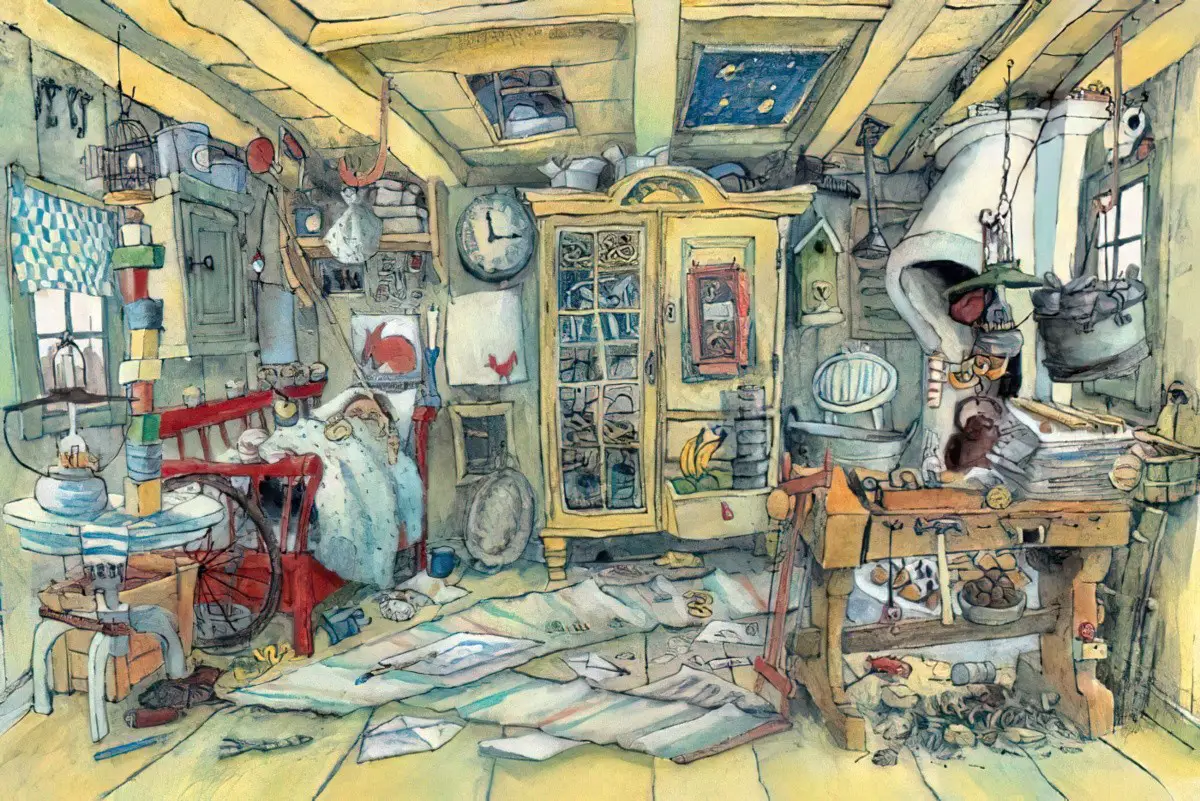

EXAMPLE FIVE: A MESSY BEDROOM

Can you think of one from your own life?

EXAMPLE SIX: A BOY’S BEDROOM

Here’s an Australian example:

On the ninth of December 1998, twenty-eight days before the awakening, five months after the car accident that gifted my mother her chronic back pain, she woke me with a kiss on the forehead.

‘Happy birthday to you, happy birthday to you.’ My bedroom blind rattled. ‘Happy birthday, dear Parker, happy birthday to you.’

I opened my eyes. My mother stood by my bed with her hands on her hips The wall behind her was blank; sometime during the night, the Lion King poster had fallen down again. It now formed the top layer of debris on my desk, above the uncapped markers, reams of drawing paper, chip packet Tazos, Nintendo magazines and stones I’d found at school.

‘Come and open your presents.’

I followed her into the kitchen. The air was musty, the linoleum tacky after days of continuous air conditioning. Stacked on the dining table was a modest pile of wrapped presents. On the slop beyond the kitchen window, the gums warped and shimmered in what must have already been furnace-like heat.

Denizen by James McKenzie Watson, 2022, rural gothic thriller and winner of the Penguin Literary Prize

EXAMPLE SEVEN: A SCANDINAVIAN NOOK BEDROOM

The illustration below is by English-Australian writer/illustrator Inga Moore and is set on a ship, but the bed is very similar to those in Scandinavian cottages.

In English they’re called Scandinavian box beds.

EXAMPLE EIGHT: A CHILD’S BEDROOM OCCUPIED BY AN ADULT

A vigil slips. But only because it has to. Only because sleep can’t always be staved.

Moongleam bleeds silver through cheap lace curtains. The window is shut, the trapped air hot. Dry and stifled.

This is a child’s room. Still. With a child’s adornments, but without a child.

On the wall is Mickey Mouse, redshorted and ringed by numbers. His arms frozen wide open. Splayed, like he’s ready to be dissected. The thin red secondhand doesn’t move or tick or tock. It just offers a determined, stunted flicker (stuck, stuck, stuck).

But Mickey grins a plastic grin and points gleefully at the numbers Three and Nine.

It’s three forty-five. It’s lightyears from midnight.

There is no music.

The bed has sloughed its covers. There are only two sheets (plastic under polyester) and there she lies. Supine. Thin and sweatglossed. You can see her rack of ribs embossing cotton.

She lies and she doesn’t toss, doesn’t welter. She’s pinned rigid, like she’s strapped down, held, like she’s ready to be…

If you look closely though, you can see how her eyelids fibrillate. Rapideyemovement. They flicker like a projection reel.

Ruburb by Australian author Craig Silvey, the opening to his first novel in 2004.

EXAMPLE NINE: A SLEEPING PORCH

Here was this man Tom Guthrie in Holt standing at the back window in the kitchen of his house smoking cigarettes and looking out over the back lot where the sun was just coming up. When the sun reached the top of the windmill, for a while he watched what it was doing, that increased reddening of sunrise along the steel blades and the tail vane above the wooden platform. After a time he put out the cigarette and went upstairs and walked past the closed door behind which she lay in bed in the darkened guest room sleeping or not and went down the hall to the glassy room over the kitchen where the two boys were.

The room was an old sleeping porch with uncurtained windows on three sides, airy-looking and open, with a pinewood floor. Across the way they were still asleep, together in the same bed under the north windows, cuddled up, although it was still early fall and not yet cold. They had been sleeping in the same bed for the past month and now the older boy had one hand stretched above his brother’s head as if he hoped to shove something away and thereby save them both. They were nine and ten, with dark brown hair and unmarked faces, and cheeks that were still as pure and dear as a girl’s.

the opening two paragraphs to Plainsong, a 1999 novel by Kent Haruf

EXAMPLE TEN: A QUIET, OMINOUS BEDROOM

He went upstairs once more. In the bedroom he removed a sweater from the chest of drawers and put it on and went down the hall and stopped in front of the closed door. He stood listening but there was no sound from inside. When he stepped into the room it was almost dark, with a feeling of being hushed and forbidding as in the sanctuary of an empty church after the funeral of a woman who had died too soon, a sudden impression of static air and unnatural quiet. The shades on the two windows were drawn down completely to the sill. He stood looking at her. Ella. Who lay in the bed with her eyes closed. He could just make out her face in the halflight, her face as pale as schoolhouse chalk and her fair hair massed and untended, fallen over her cheeks and thin neck, hiding that much of her. Looking at her, he couldn’t say if she was asleep or not, but he believed she was not. He believed she was only waiting to hear what he had come in for, and then for him to leave.

Do you want anything? he said.

She didn’t bother to open her eyes. He waited. He looked around the room. She had not yet changed the chrysanthemums in the vase on the chest of drawers and there was an odor rising from the stale water in the vase. He wondered that she didn’t smell it. What was she thinking about.

Then I’ll see you tonight, he said.

He waited. There was still no movement.

All right, he said. He stepped back into the hall and pulled the door shut and went on down the stairs.

As soon as he was gone she turned in the bed and looked toward the door. Her eyes were intense, wide-awake, outsized. After a moment she turned again in the bed and studied the two thin pencils of light shining in at the edge of the window shade. There were fine dust motes swimming in the dimly lighted air like tiny creatures underwater, but in a moment she closed her eyes again. She folded her arm across her face and lay unmoving as though asleep.

Plainsong, a 1999 novel by Kent Haruf

EXAMPLE ELEVEN: A SMALL OBJECT SPARKS A MEMORY

In a New York City bedroom, two 24-year-old bffs sleep in the same bed. The intimacy of sleeping together is contradicted by the narrator’s withholding information:

We laugh until we’re too tired to make any more noise. Vera flops onto her back. Our breathing slows. The room is dim except for the glow-in-the-dark star that clings to the ceiling.

“Where’d you get that?” she asks, as if she hasn’t slept in this bed countless nights, staring up at that very star. She points to it with her chin. “How come there’s only one?”

“Some guy gave it to me,” I lie. In fact, I stole it from a party in Harlem at a friend of a friend’s place. The apartment was hot and crowded, so I wandered deeper inside, looking for a space of my own. I landed in a closet-sized room with a shadeless lamp and a mattress on the floor, a single wall coated in stars. I peeled one off with my thumbnail and slid it into my purse.

“My mom wouldn’t let us have those stars,” I tell Vera. “I don’t know why. She would have liked them.”

“It’s weird how you talk about your family,” she says. “Like they’re dead.”

I choose not to respond, letting sleep take over. Next morning, I’m barely conscious when Vera slips out with her suitcase.

Mother In The Dark, a 2022 novel by Kayla Maiuri

EXAMPLE TWELVE: A TINY-BUDGET CITY BEDROOM

For some mysterious reason, there was a giant broken mirror resting against one of the walls, and I never bothered to remove it despite the obvious danger. I just used it to look at the lower half of my outfits and pretended the sharp edges couldn’t possibly hurt me.

I was so broke that I slept on an air mattress for the first two months. Some nights, I’d wake up flopping all over the place when it had deflated. Needless to say, I slept like absolute shit, and I would have continued to do so if one of my aunts hadn’t bequeathed me her old bed. My books, my most prized possessions, were stacked on industrial shelves that were likely purloined from a factory. And I didn’t have a closet, so the clothes that didn’t fit in my dresser (did I even have a dresser?) were strewn all over the place. When it was hot, I writhed in bed all night without an air conditioner; in the winter, I wore layers of clothes to keep from shivering. Another friend visiting me one evening took one look around and said, in disbelief, “Wow, you live like Charlie from Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory.” I was mildly insulted, but proud nonetheless to be living on my own with no one else’s help.

from Crying in the Bathroom, a 2022 memoir by Erika L. Sánchez

EXAMPLE THIRTEEN: A GRANDPARENT’S FARM HOUSE BEDROOM FROM A CHILD’S POINT OF VIEW

I was so young then I was put to sleep in a crib—not at home but this was what was kept for me at my grandma’s house—in a room across the hall. There was no fan there and the dazzle of outdoors—all the flat fields round the house turned, in the sun, to the brilliance of water—made lightning cracks in the drawn-down blinds. Who could sleep? My mother’s my grandmother’s my aunts’ voices wove their ordinary repetitions on the verandah in the kitchen in the dining room…

“Images” by Alice Munro (1968)

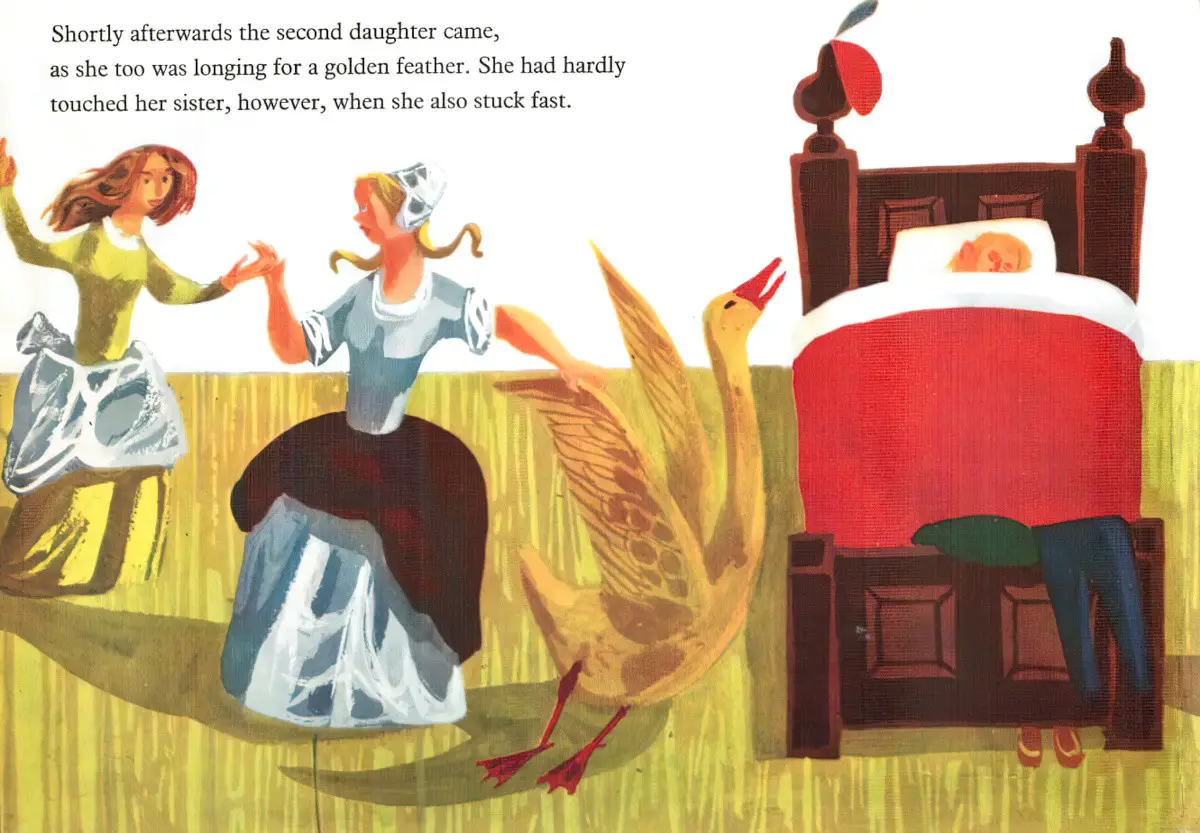

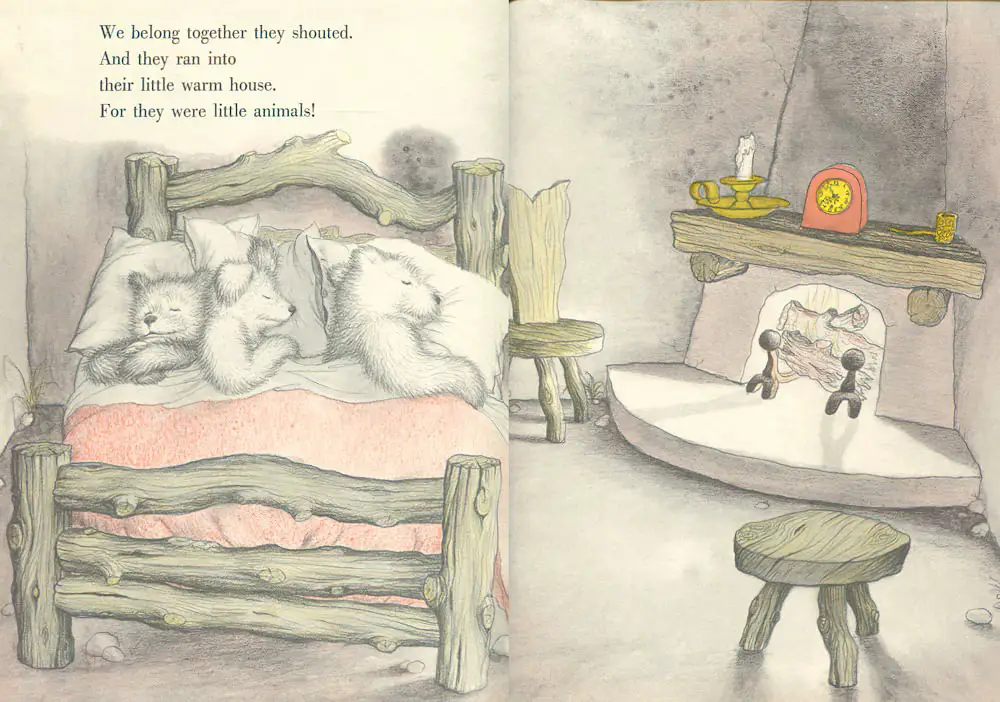

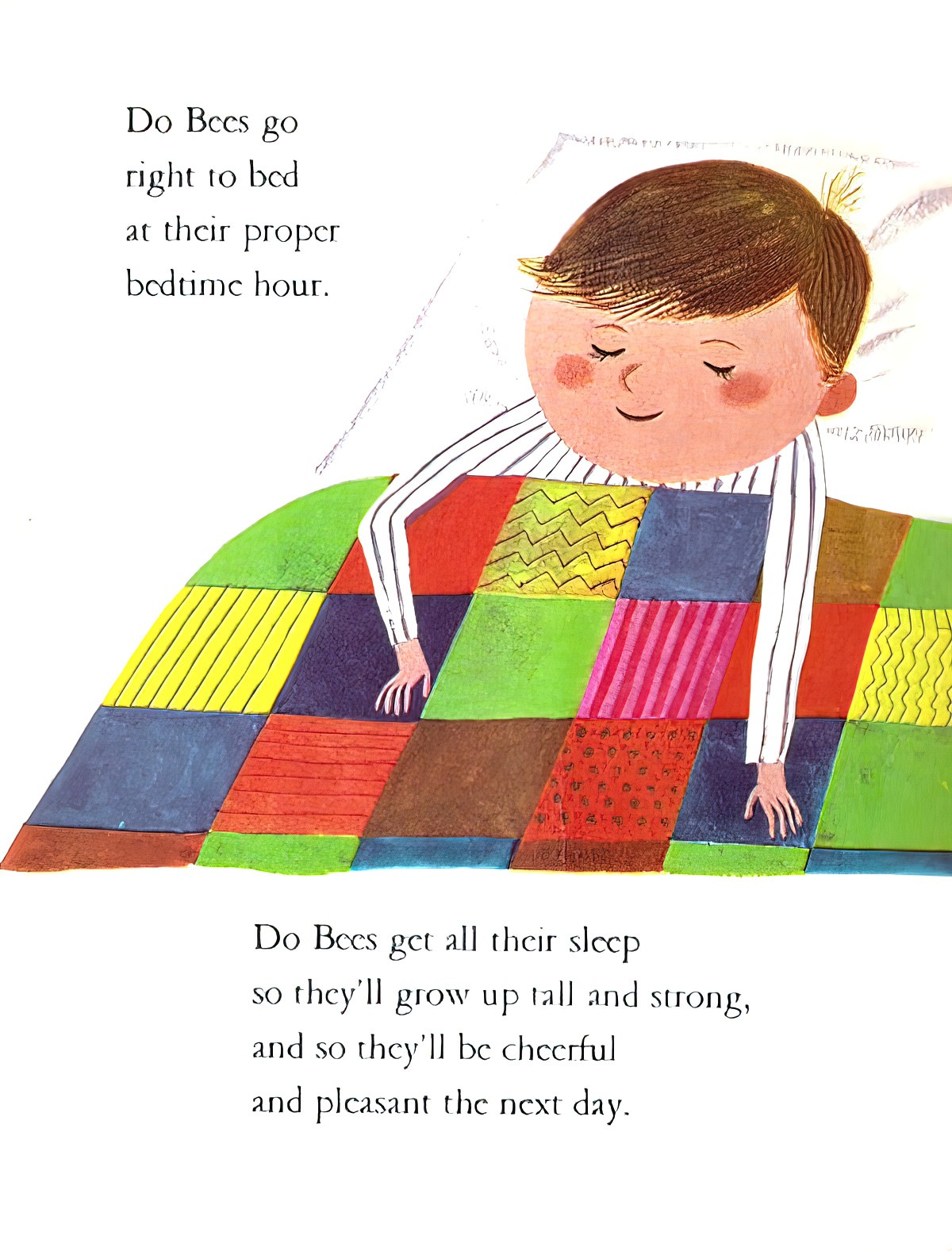

BEDROOMS IN CHILDREN’S STORIES

A typical home-away-home children’s story takes place over the course of a single day, and ends when the child is tucked safely into bed at night. No surprise, then, that Western children’s books feature many examples of illustrated bedrooms.

Note that tucking a child into their own bed at night is a specifically Western thing to do. Many non-Western children co-sleep with their parents until adolescence.

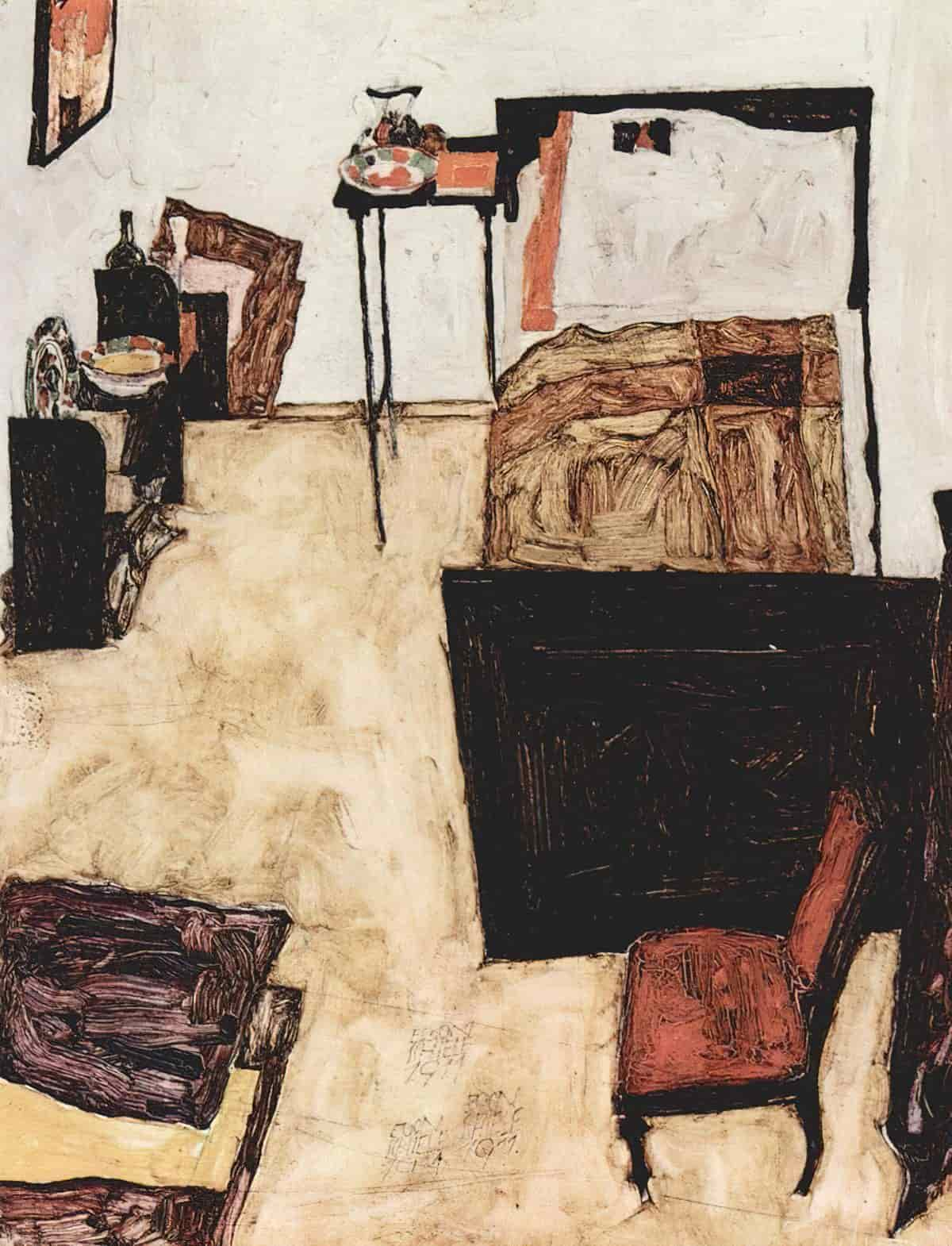

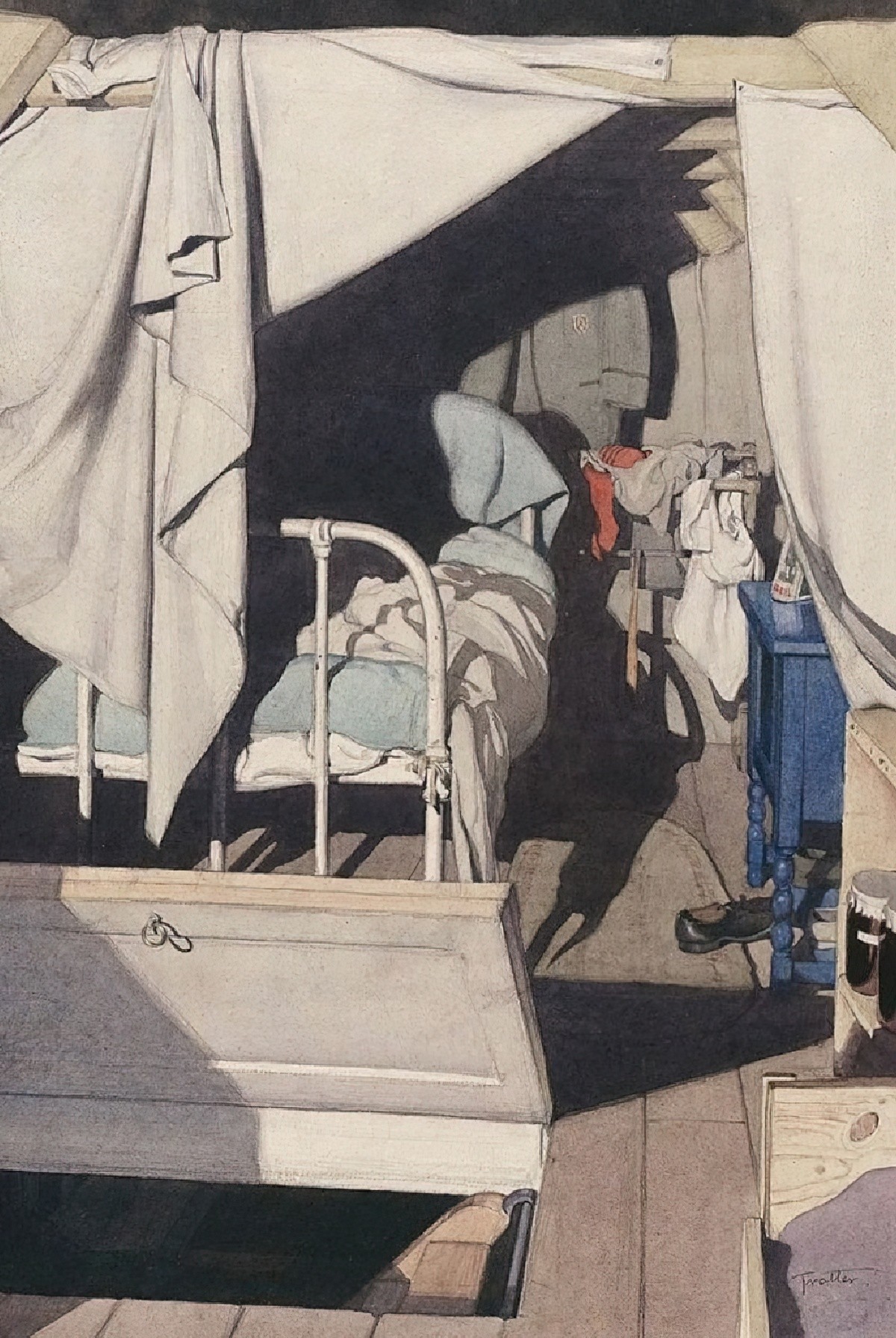

BEDROOMS IN FINE ART

SEE ALSO

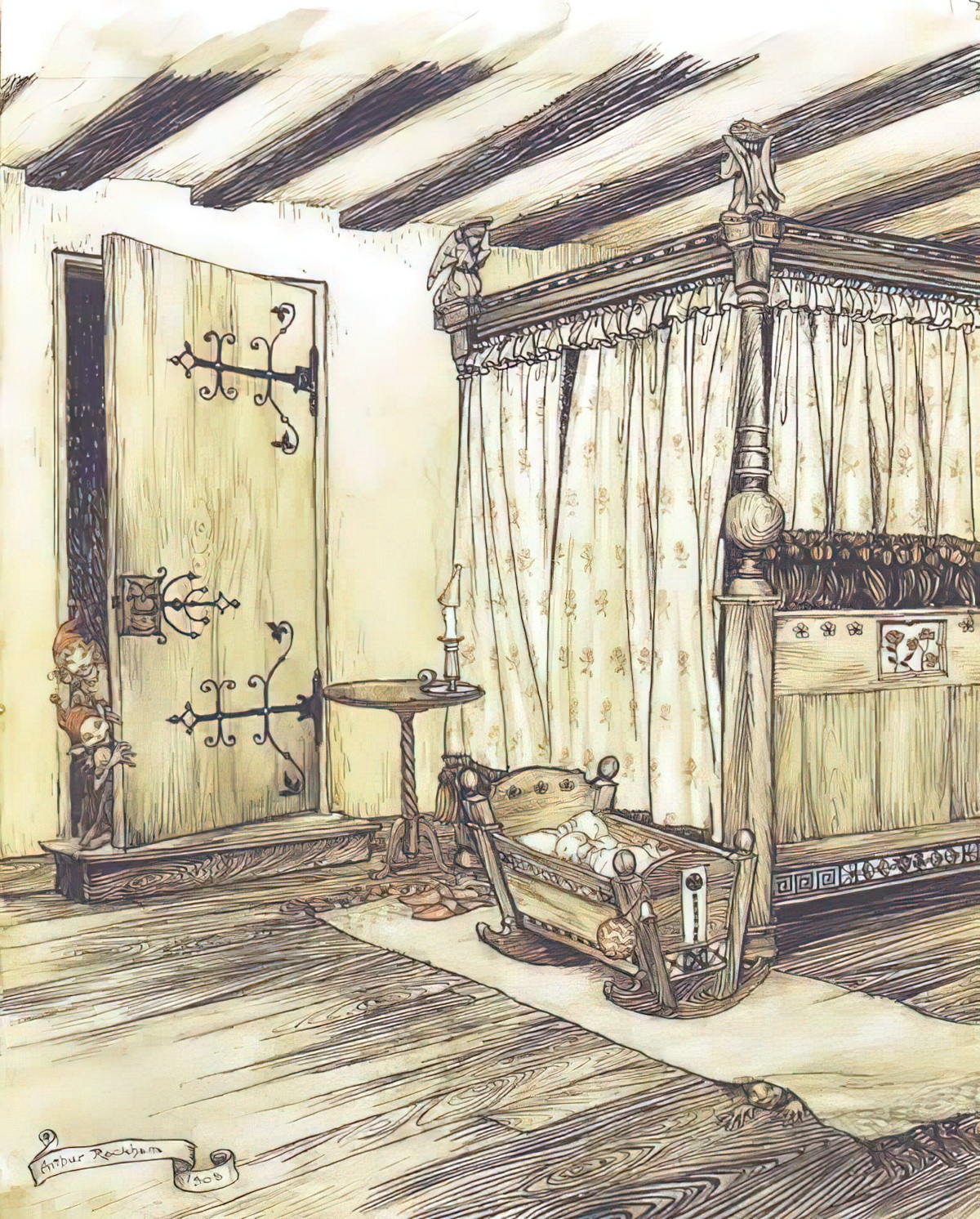

CRADLE TRICK: A sub-category of the “bed-trick,” this is a folk motif in which the position of a cradle in a dark room leads one character to climb into bed with the wrong sexual partner. It appears prominently in Chaucer’s “The Reeve’s Tale.” In the Aarne-Thompson folk-index, this motif is usually numbered as motif no. 1363.

Literary Terms and Definitions

The Bed: Laurie Taylor explores the social history of the bed and considers the chequered fortunes of the twin versus double bed at the Thinking Allowed podcast (BBC 4).

Teenage Bedroom is a Tumblr with photos of … well, it’s pretty self-explanatory. What vibe do you get from each of these bedrooms? Can you associate any with characters from novels you have read?

Rolled over: why did married couples stop sleeping in twin beds? A new cultural history shows that until the 1950s, forward-thinking couples regarded sharing a bed as old-fashioned and unhealthy from The Guardian

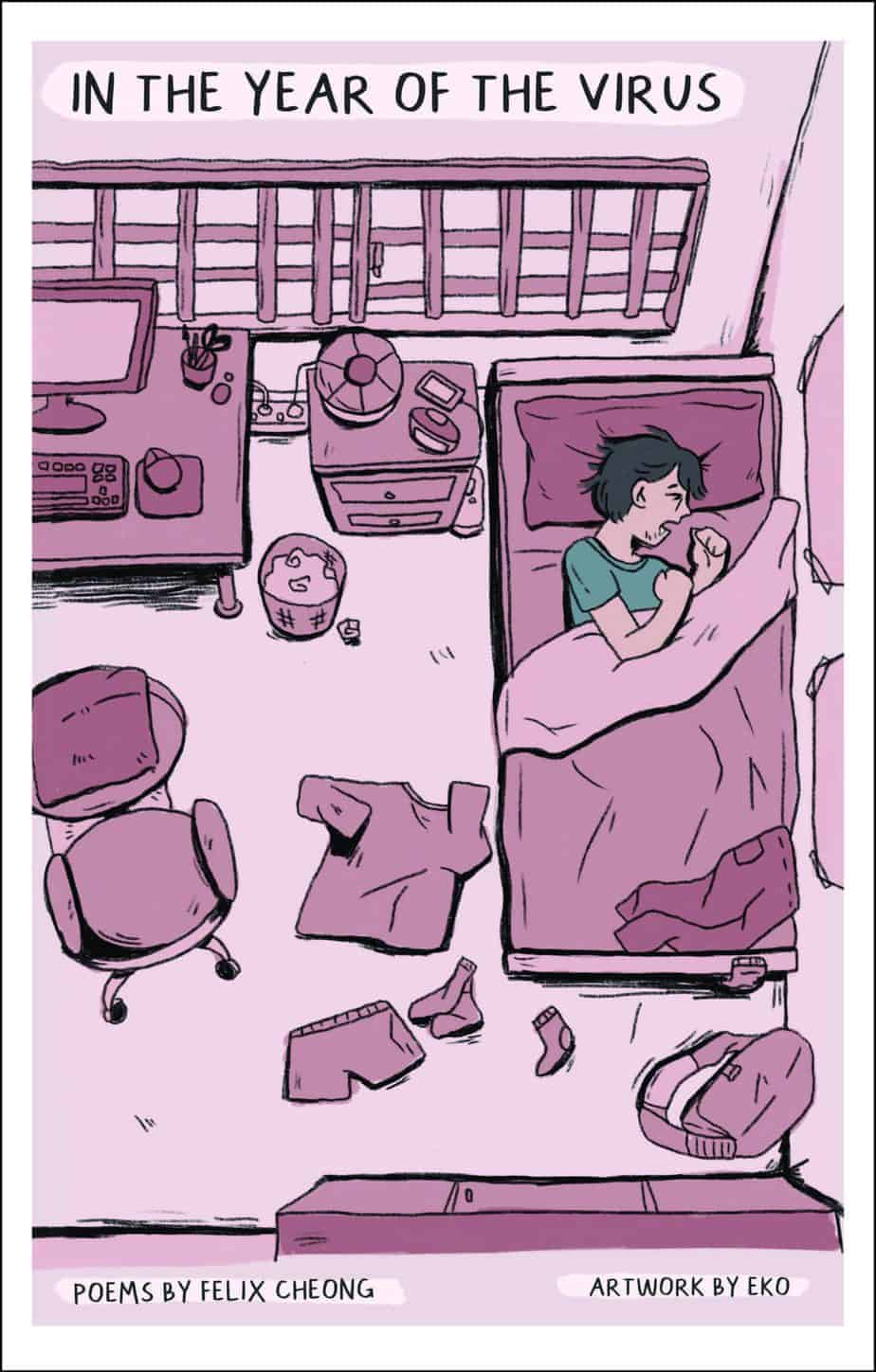

In the Year of the Virus is an innovative graphic comic book inspired by the Covid-19 pandemic. The story revolves around several characters affected — and infected —- by the viral outbreak. The text by award-winning writer Felix Cheong, adapted beautifully by artist Eko, examines our humanity as our lives are upended and ended.

This is a ground-breaking work that marries text with artwork and aptly captures the wild swings of emotion we all felt after the pandemic hit and the lockdown began.

Header illustration: Pets for Peter, 1950, Aurelius Battaglia, Italian American Children’s Book Illustrator