“At the Bay” (1921) is considered one of Mansfield’s best short stories, by a writer at the height of her powers. This is one of the three about the Burnell family, who also star in “Prelude” and “The Doll’s House“.

“At The Bay” is an interesting case study for writers, for so many reasons. Notably:

CHARACTERISATION

The way Mansfield creates her characters in pairs, to compare and contrast them. If one character goes visiting, so does her counterpoint character.

ANTI-EPIPHANIES

This is an example of a story in which no one has any big self revelation. Like Mad Men famously achieved, the characters go about their own lives, continuing to make mistakes, learning little, and that is how life really is. This is the ultimate realism, though it can feel to the reader like ‘nothing happens’. We tend to say of these stories, ‘It’s not got any plot’. Or, it’s an ‘anti-plot’.

A GREAT EXAMPLE OF A LYRICAL SHORT STORY

But apart from the lack of growth, “At The Bay” does conform to classic story structure, and even the lack of Anagnorisis is replaced by characters who suddenly change their emotional valence, either because they are practising ‘opposite action’ or because they suddenly become scared or whatever.

MASTERFUL CHANGES IN EMOTIONAL VALENCE

Mansfield’s scenes each feel complete in their own right because the emotional valence changes from beginning to end. Linda starts off with no emotional affect, but ends the scene beaming at her baby boy. Beryl starts off scared with Mrs Kember than feels jubilantly free for a second. Stanley rushes into the water triumphant to be first. He is immediately irritated to find he is not first after all. Mansfield’s emotions swing from one extreme to the other. If we find our own scenes emotionally flat, a read of “At The Bay” should set us back on the right track.

DEPICTION OF A CHILD’S POINT OF VIEW

Mansfield also has a real affinity for children. She recreates play scenes and child interactions so authentically, without glossing over the fact that the hierarchy between children can be brutal. There’s nothing mawkish about these children.

THE ARCHETYPAL EXAMPLE OF ‘ENCLOSURE TECHNIQUE’

The story divides into twelve sections. Mansfield is using the ‘enclosure technique’.

The prototype of the enclosure technique is in “At The Bay”, where themes, characters and settings of the 12 sections are structurally enclosed, presenting the different characters in their activities, thoughts, fears, fantasies and dreams, from dawn to dusk. The enclosure -technique functions structurally and thematically.

Each of the sections in “At the Bay” are juxtaposed, by different points of view, imagistic patterns and all the sections co-exist, not in subordination but in juxtaposition. All the various sections, with all the different perceptions of life, like pieces of coloured glass pierced by various shafts of light, form the episodes in the lives of the Burnells and Trouts. Life is just as random as that. The enclosure-technique is used as a unifying force.

Julia van Gunsteren, Katherine Mansfield and Literary Impressionism

Mansfield illustrates her own attitude towards the events that shape a life. Life comprises a series of moments just like these. This montage of scenes is therefore a recreation of the haphazardness in life. Or in other words, the structure of the story works symbolically. That interaction between form and meaning is a feature of modernist writing.

STORY STRUCTURE OF “AT THE BAY”

Like James Joyce’s Ulysses (1922) and Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway (1925), ‘At the Bay’ covers just one day from different points of view. Modernist writers followed the example of cubist artists, who used multiple perspectives to delineate their subjects.

Beryl Fairfield has become friendly with a controversial figure, Mrs Harry Kember: ‘the only woman at the Bay who smoked’. The other ladies consider her ‘very, very fast. Her lack of vanity, her slang, the way she treated men as though she was one of them, and the fact that she didn’t care twopence about her house and called the servant Gladys “Glad-eyes”, was disgraceful’. It is widely assumed that her husband must have married her for her money.

Linda Burnell, Beryl’s sister, is married, with children; Beryl is single and childless; neither woman has found fulfilment. Beryl indulges in fantasies about a lover, and in the final scene she is propositioned by a man. Although she recognises him, the reader is kept waiting. Her feelings fluctuate: initially, she senses the possibility of achieving her desire for ‘a new, wonderful, far more thrilling and exciting world than the daylight one’. When Beryl reaches the gate, she becomes terrified: ‘The moonlight stared and glittered; the shadows were like bars of iron’. Harry Kember urges her on; yet she fears the ‘little pit of darkness’ beyond the fence. Ultimately, Beryl faces a moment of understanding and, again, the reader wonders what her prospects will be subsequently.

An Introduction To Katherine Mansfield’s Short Stories

Each of the characters have their own shortcoming (described below). If there’s a ‘main’ character it’s Beryl, the unmarried sister. She longs for freedom. But she’s terrified of freedom. (Considering whether a main character achieves freedom or increased slavery is one interesting way of looking at story arc.)

Beryl has no Anagnorisis at the end when her friend’s husband comes to her bedroom window to seduce her — instead she retreats into herself, which is ostensibly the opposite of what she longs for. She longs for admiration and freedom, but remains hampered by her fear of danger.

SETTING OF “AT THE BAY”

This is the story of an upper-middle-class household near Wellington in colonial New Zealand. This is a constricted social environment where gossip can run rife.

PRELAPSARIAN SETTING

Prelapsarian means ‘before the Fall’, and describes a kind of utopia. Stories aimed at a child audience often open this way. The Prelapsarian setting of “At The Bay” illuminates the world of childhood, where nobody knows the answers to certain, fundamental questions.

“At the Bay” opens with a panoramic, utopian description of the bay. A camera-like eye follows the shepherd, his sheep and the dog. We also have details such as a murmuring, sleepy sea. Mansfield transfers the epithet of ‘sleepy’ from the characters to the sea, bringing the entire world to life.

MUSICALITY

Phonology underlines the lullaby feel of this Prelapsarian world.

Sibilance: a hissing sound is created within a group of words through the repetition of “s” sounds.

Take note of the sibilance in the passage below:

the sound of little streams flowing, quickly, lightly, slipping between the smooth stones, gushing into ferny basins and out again. … a faint stirring and shaking, the snapping of a twig and then such silence that it seemed someone was listening

Assonance: the rhyming of two or more stressed vowels

The eye switches to Stanley Burnell. In “Prelude“, dark bush surrounds the house and garden. In “At the Bay”, the story moves in and out of the house to the sea and shore. But the characters seek answers to the same questions.

This time, The Burnell Family go to the beach, finding a new environment in which to explore their interactions and their philosophies on life and death.

IMAGERY IN “AT THE BAY”

This is Mansfield’s attempt to demonstrate in art the triumph of:

- beauty over ugliness

- mystery over simplicity

- artistic knowledge over nature’s baseness

Mansfield deftly sets up the themes and imagistic pattern in the first section by describing the microcosm of the bay in detail. Sea and earth merge together: a metaphorical statement of the mutability of time and life.

Sheep Bleating

The children hear sheep in their dreams. Later they will face fear.

The dog

The dog’s natural impulse is to frolic. But due to training she trots beside her master. The characters, too, must maintain control over their impulses and natural inclinations. When the dog runs from the path onto a rocky ledge and ventures too far she retreats hurriedly,. The human characters will do the same thing during the day to come.

Also, the Trouts’ dog (Snooker) sleeps on the steps of one of the bungalows, He he looks dead. This suggestion of mortality sets the tone for the conversation to follow between Kezia and her grandmother. (If it influenced plot we’d call it ‘foreshadowing‘.)

The eucalyptus tree

Mansfield does a lot with trees and plants, whether it’s the aloe in “Prelude“, the beech tree in “The Escape“, the pear tree in “Bliss“, and a vast selection of drooping and bowing personified flowers, which to Mansfield have psychological meaning for her characters.

Something immense,’ like an ‘enormous shock-haired giant with his arms stretched out.

A meeting will take place there. Alice hurries towards it when spooked about being on the road alone. She will duck inside to see Mrs Stubbs who is going to have a photograph of a giant fern tree enlarged, a continuation of the phallic imagery. (Alice dwells on size.)

Like the aloe in “Prelude“, the gum tree serves as a symbol of sex (birth) and death. This is part of what makes “Prelude” and “At The Bay” feel like a diptych (a single image across two separate canvases).

The manuka tree

Its blossoms will fall and scatter and be brushed aside as ‘horrid little things’. The blossoms symbolise Linda’s questions about the meaning of life. Linda sees herself as a leaf blowing about. She feels there’s no escape. But unlike the scattered blossoms of a tree, life offers Linda sensual pleasures. Her question is partially answered when she sees her baby smile. As in “Prelude“, Mansfield presents Linda as an earth-goddess by showing her connection with nature and specifically with the tree.

On this point, the Japanese manga (and also animated film) 5 Centimeters per Second would make a good compare and contrast.

As you probably guessed, cherry blossoms are highly symbolic in Japan.

The encounter between the dog and the cat

This foreshadows the encounter between Beryl and Harry Kember.

There has been some time lapse since the readers met these characters in “Prelude” but there have been no significant changes in their relationships and routines. This is in line with Mansfield’s underlying thesis:

- People are essentially unchanging

- Time is constant

- People and time continue on an unbroken line that extends from the past into the future, crossing the present.

The Tide

Here’s the thing about beaches — this is where the land meets the sea. Seems obvious, but worth pointing out because when there’s a beach in a story, this points out attention towards something else merging. The significance of water in “At The Bay” is apparent from the opening passage, with mention of the sea, the dew.

What’s merging here, in this story?

Well first, life and death are unified.

There’s this Jungian idea that water is an ever-moving, feminine flow and Katherine Mansfield utilised that. The bay, as a body of water, bears a heavy weight of historical, mythical and psychological meaning.

For more on that, see The Symbolism of The Ocean. In “At The Bay”, the ocean symbolically rises to meet the characters — in the first scene, two of the characters are literally in the water. Later, Beryl and Mrs Kember enter the water, but at other times as well, the characters feel the ocean meets the bungalow. These characters are living in a kind of liminal space, symbolised at that point ‘where the ocean meets land’, but also in terms of freedom vs. liberation, and in terms of their sexuality, both exciting and scary at once.

Freedom

The illusion of freedom is central to “At the Bay”.

Linda gave up a life of travelling to marry a man she loves only sometimes. She has conformed to society’s expectations by having children and tending to her husband, though there are many times she doesn’t feel great love towards any of them.

Then Linda is seduced by the sight of her baby boy lying on the grass beside her. She experiences joy, another form of motherhood’s entrapment.

When Jonathan tells her he feels like an insect trapped in a room, he is explaining a variation on the same theme: ‘something infinitely joyful and loving’.

Likewise, Jonathan Trout imprisons himself in an office for all but three weeks of every year. Unable to find a way to escape, he thinks he would rather be a prisoner in a jail.

Even the sheep are controlled by the dog, but the dog is inhibited by the cat on the fence. As Bob Dylan said, ‘You have to serve somebody.’

Freedom is symbolised by the water and each character’s attitude towards it:

- Linda wants to escape ‘up a river in China’ but, ironically, is the only character who doesn’t go to the water at the bay during the day.

- Jonathan Trout is a ‘trout’ in the water with a comically symbolic name. He gives himself to life easily and wholeheartedly yet is inhibited by his job.

Life and Death

Kezia asks her grandmother about death, but neither of them understands the nature of it. The grandmother’s way of dealing with grief is to think on it for a short time then put it out of her mind. The uncomfortable conversation Kezia tries to initiate about the dead relation turns into a game of love and affection. The meaning of life and death ultimately escapes them.

The grandmother, and Kezia, under her influence, are practising what we now call ‘opposite action’. This skill is part of dialectical behaviour therapy. Marsha Linehan developed this therapy in the 1990s as a modified version of cognitive behaviour therapy.

This is probably an evolution on the work of vitalist psychologists such as William James. Mansfield definitely read James and found his work fascinating. A main idea (radical at the time) is that actions and emotions are more of an interacting cycle. Beforehand people thought that we behave a certain way because we feel a certain way, and that’s all that was to it. When the grandmother decides to do something fun with her granddaughter rather than continue to think sad thoughts, she is practising ‘opposite action’.

When Lottie sees the face at the window and screams it’s not simply that the children have overactive imaginations, but also that they understand something about death: an intuitive understanding, symbolised by Jonathan’s bearded face.

Life and death merge on some other plane which transcends human experience. The characters see them merge at points throughout the story: The rock pool becomes a microcosm of the universe. Beneath the water there is a glimpse of the unknown.

Linda contemplates mortality sitting under the bush. The flowers fall as soon as they flower. And when Mrs Fairchild and Kezia take a nap, the peaceful rest itself is a prelude to death.

Connected to this is the theme of…

Darkness and Light

A pattern throughout the story is contentment and joy followed by disappointment and disillusionment. This is like the natural cycles of the earth: night, day, night, day. This is evident as the story takes place over the course of a day, in itself measured by darkness and light.

The story does end on a positive note; we know that the next day will follow.

See also: The Symbolism of Darkness and Night

CHARACTERS OF “AT THE BAY”

Mansfield describes the activities of characters against the background of ocean tides. In “Prelude” she used the waxing and waning of the moon to this end.

The group of characters in the story correspond very closely to the extended family in which Mansfield, as Kathleen Beauchamp, grew up. Kezia Burnell; her older sister, Isabel; and the younger Lottie correspond respectively to Kathleen, Vera (or Charlotte), and Jeanne Beauchamp.

“The boy” (as the baby in the story is called) occupies Leslie’s position in the family and bears his nickname. The Burnell parents, Stanley and Linda, closely resemble Harold and Annie Beauchamp. Linda’s unmarried sister, Beryl, and their mother, Mrs. Fairfield (a bilingual pun on “Beauchamp”), live with the family, as did Annie’s sister (Belle) and mother (Mrs. Dyer).

Sharing the Burnells’ holiday at the beach are Linda’s brother-in-law, Jonathan Trout, and his two boys (Pip and Rags). Their surname mocks that of Kathleen’s uncle, Valentine Waters, and his sons, Barrie and Eric. The Crescent Bay of the story corresponds to Muritai Beach (across the harbor from Wellington city), where the Beauchamps and the Waterses spent their summer holidays.

Encyclopedia.com

Stanley

Stanley fancies himself in a class of his own. If he fails to be first in the water, he will let this insignificant battle ruin his morning. He plays games of substitution to make his life seem smoother. But he is constantly plonking himself in competitive battles. For Stanley, life is a zero sum game. Everything is a business and he must negotiate profitably. He doesn’t want unnecessary human interaction. Stanley’s time is precious. By avoiding what he considers ‘time wastage’, Stanley has his own way of dealing with the unwelcome knowledge of mortality.

- Stanley engages the entire household in a race against time to find his cane. When Linda breaks a rule he penalises her. He does not say goodbye. But he has to wave to avoid losing face in public.

- Stanley recoups his losses by bringing home gloves. He feels guilty, and his ‘love language’ is to buy a present in lieu of saying sorry.

Jonathan Trout

Stanley’s brother-in-law also plays games but of a completely different sort. He role-plays in a game of masquerade to hide his overall dissatisfaction with his lot. He is a smart man in a menial job (as a clerk) and probably consoles himself with the knowledge that deep down he’s smarter than most other people, including people who out-earn him. Case in point, his ridiculous brother-in-law, who he likes nonetheless.

His older son Pip resembles him in looks: dark hair and eyes with pale skin, tall and lanky.

His surname — that of a fish — makes him seem a little ridiculous to the reader, especially as we first meet him in the sea.

Beryl Fairfield

Beryl is an unusual character because on the one hand she lives in a dream-world, hoping that one day her prince will come to rescue her, and on the other hand, is not naïve to the ways of the world. She understands the dynamic between the Kember couple, for instance.

Beryl’s play-acting, like Jonathan’s, allows her to escape her unsatisfactory life but she is her own audience. She plays games to evade knowledge of the meaning of life. Beryl is childlike. The children are capable of seeing a piece of green glass as a beautiful emerald as big as a star. This is how Beryl is able to imagine herself.

All of these games, played by the adults, juxtapose against the innocent games played by the children. What does this tell the reader? All of life is make-believe, with rules, penalties and rewards.

Beryl’s attempts to ‘discover herself’ juxtapose against Lottie’s efforts to compete with her older sisters. Lottie is frequently left behind, sometimes literally. She is unable to navigate a stile. Sometimes she can’t grasp the rules of a game.

Similarly, Beryl fears she is missing out on life as a spinster. When Lottie screams at the whiskered face in the window this foreshadows Beryl freezing in horror when a man appears outside her bedroom window later.

For Beryl, the day at the bay is a frustrated attempt to find a life and lover. Stanley can see there is something wrong with her humour; Beryl is mindful of Stanley and cross with Kezia over breakfast. Beryl’s humour changes when she stops the coach and has a chance to socialise with one of the passengers. She is also happy when Stanley leaves – a feeling shared by all the women in the Burnell household. “Their very voices were changed as they called to one another…”

Is Beryl bisexual? I don’t think so, necessarily. I think she enjoys any kind of sexual attention from anyone, but my guess is that sex with any gender scares her to death. As Mansfield shows us in “Prelude“, her fantasies cease before any actual physical interaction, stopping at the romantic ‘prelude’ in which lovers first meet and the man declares his infatuation.

Linda Burnell

Linda Burnell is one of three daughters. (One is Beryl; the other is the unnamed mother of Rags and Pip). Linda is half-way between youth and age. She has three daughters of her own, replicating the structure of her natal family. Isabel, the eldest, remains an undeveloped character — the caricature of a bossy big sister. Linda aligns most closely to Kezia, as they share the same concerns. (In the same vein, Lottie’s concerns reflect those of Beryl.)

This kind of juxtaposition of characters affords a sense of continuity to the story; a sense that time exists beyond the single day spent “At the Bay”, that time stretches over generations and beyond. Mansfield does the same in “Prelude“, using various symbols.

Mansfield explores the themes of identity and sexual conflicts via the character of Linda. Her father once promised that they would both run away together. That didn’t happen; Linda found Stanley instead, as a substitute for her father. Her baby boy holds a hope for Linda’s expression of her masculine side.

Today we attach words to psychological conditions and we might say Linda Burnell is dealing with postpartum depression. She has no strong feelings for her baby. We now know how common perinatal depression is, so it’s hardly a radical reading of the text. Added information we understand after “Prelude“: Linda has been told she has a weak heart, and child bearing may kill her.

This also applied to Mansfield’s own mother, but biographers wonder if Mrs Beauchamp really had anything wrong with her. When society required women to have baby after baby after baby until menopause, declaration of a weak heart was about the only way for a married woman to control her own fertility.

The Stanley Josephs Family

The Josephs Family provides a neat contrast to the Burnells. In comparison, the Josephs family is vulgar and bad-mannered. (Their lady-help blasts on a whistle and hands out dirty parcels. The basin of fruit-salad has turned brown. The children play ‘like savages’.) Meanwhile, Mrs Fairchild sits genteel in her lilac cotton dress and black hat. The Burnell children no longer play with the Samuel Josephs children, nor do they attend their parties. A similar white class snobbery comes fully to the fore in “The Doll’s House“.

Mrs Kember

Depicted as sinister. Notorious locally because she refuses to conform to societal conventions, including what it means to be a woman. The landscape reflects this nebulous way of living. The shoreline itself blurs the boundary between sea and land. (For more on this see my posts on liminal spaces and beach as setting in stories.)

Although Mrs Kember has money, she breaks social conventions in her relationships with men and with her servants. She smokes, which makes her a ‘fast’ woman for the era. She cares nothing for her house. She does not have children in an era when contraceptives were a futuristic invention. She behaves with men as if she were one of them.

Beryl is hardly a forward looking woman herself. Why is she drawn to Mrs Kember when those other ‘ninnies’ are scared of her? Mrs Kember represents the freedom which simultaneously attracts and terrifies her. Beryl is seductive with and seduced by Mrs Kember. She becomes shy then reckless, defiant of other women on the beach. She undresses boldly and joins Mrs Kember in the water.

With her ‘black waterproof bathing cap’, Mrs Kember is the image of Satan and like Satan she is constantly shifting forms. Later that night, Beryl puts Mrs Kember’s words ‘You are a little beauty’ into the mouth of an imagined suitor.

Mr Kember

Outrageous, like his wife. Later, scary.

How did he live? Of course there were stories, but such stories! They simply couldn’t be told…

That night, Mr Kember appears outside Beryl’s window. Because the reader is used to Beryl’s habit of fantasising (especially if you’ve already read “Prelude“) we are not sure at first if she’s imagined him. But he’s not an apparition at all. Beryl goes outside to him but she is (quite legitimately) frightened. Mr Kember makes fun of her fear, not understanding the social and physical consequences of a tryst, or the very real possibility that he’s not going to take no for an answer

Naturally, Beryl is frightened. Mr Kember calls her a ‘cold little devil’ and Beryl disappears back into her bedroom. Mr Kember has become an awful inverse of a fantasy lover.

Alice the Servant Girl

Alice is constricted in this place. Like Beryl, she has nowhere to go in the evenings. Her predicament mirrors Beryl’s, who we might expect to have more personal freedom as she is not a ‘servant’ but a member of the white upper-middle-class. But socially, Beryl is just as restricted as Alice.

When Alice visits Mrs Stubbs, their encounter mirrors Beryl’s encounter with Mrs Kember on the beach. This visit emphasises the role of women as guardians of tradition. If women behave like men, tradition is threatened. Mrs Stubbs says that ‘freedom’s best’ and Alice laughs but she longs for the security of the Burnell kitchen, safe from the dangers of sex, life and freedom. Both Beryl and Alice end up retreating back inside the safety of the home.

Sex again loses its boundaries when the oedema of the dead man and the oedema of pregnancy become one in Alice’s mind. (Oedema is a condition characterised by an excess of watery fluid collecting in the cavities or tissues of the body.) Alice ends up linking death with sex, which ruins the idea of sex for her, naturally. (Roberta Seelinger Trites has theorised that sex is taboo because death is taboo.)

Alice is Beryl’s counterpoint in age. Just as Beryl seeks knowledge from Mrs Kember, Alice visits an older woman, seeking wisdom. But neither Alice nor Beryl have any luck. Neither woman is any the wiser at the end of the story. Both Alice and Beryl are puzzled when the three younger girls meet the boys at the beach, digging for treasure. “At The Bay” is therefore an example of a story in which there is no Anagnorisis, and that is the entire point.

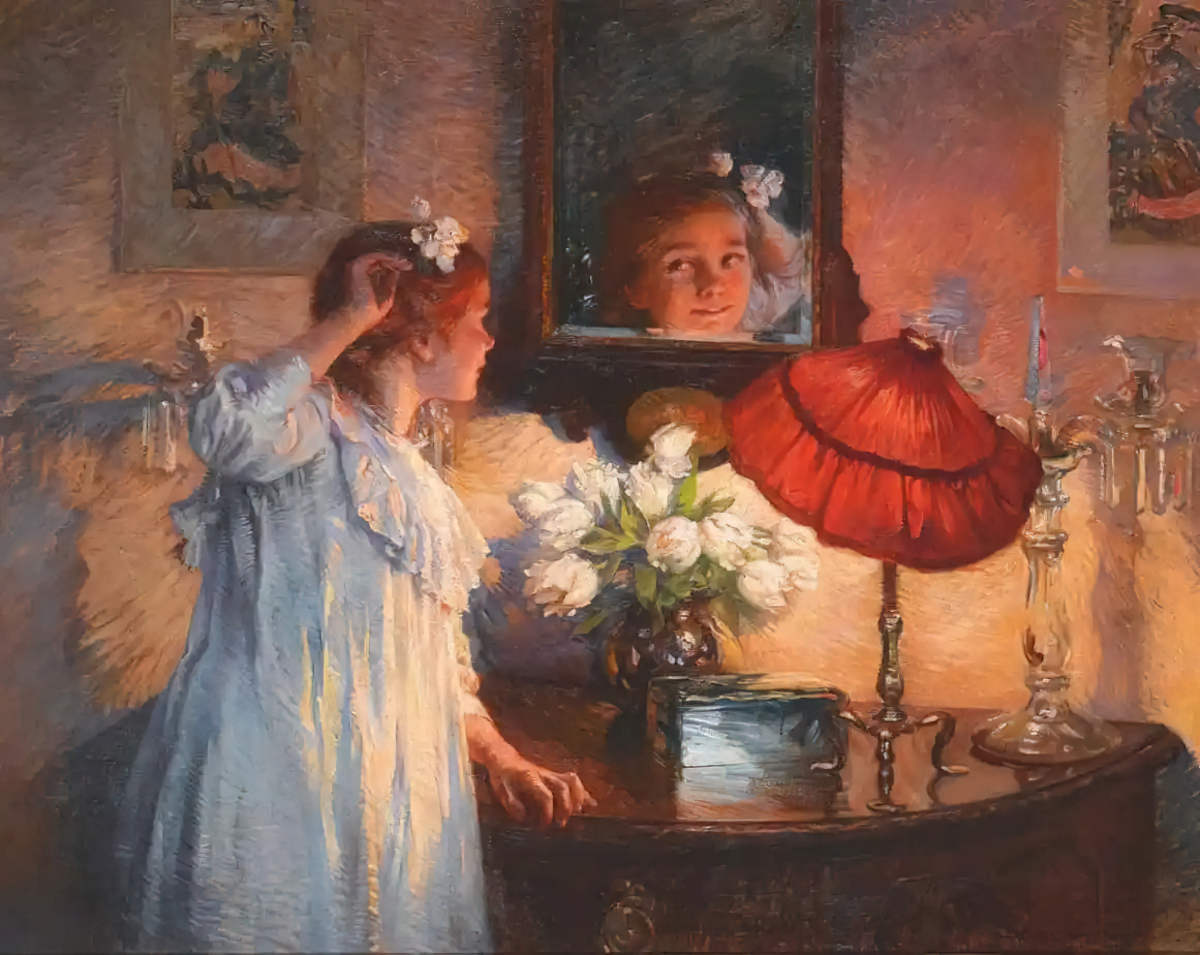

Header painting: Albert Chevallier Tayler — The Mirror 1914