Toilets are inherently scary. This holds true across cultures, even though different cultures (and even genders) experience public toilets differently. Below I take a look at a short horror story by Stephen King with a few examples of toilet horror by other authors, in which the public bathroom is utilised for storytelling purposes as a horror venue.

i think we’re in a golden age right now because in the past going to the bathroom was very gross and in the future the toilet is going to have like an ai in it that talks to you or something. so this is really the most dignified time there will be for going to the bathroom

@tinybaby

TOILETS AND JAPAN

In the final year of the last millennium I was a university exchange student, sent to a rural part of Kyushu, one of the four main island of Japan. (Kyushu is the big one at the bottom.) I was in Japan to study Japanese language. One of my Japanese language lecturers was a sociologist and, I shit you not, his area of interest (at least, that year) was bathroom culture, and how bathroom behaviour differs between Asia and the West.

I can see how he happened upon that interest. He worked with us exchange students and he must have noticed how Japanese bathroom culture is quite different from the bathroom culture of my own home countries (New Zealand and Australia).

Namely:

In Japan, you won’t find toilet doors which stop about a foot off the floor. Japanese people, in general, absolutely hate using toilets in which passers-by can hypothetically see your feet. This isn’t only to do with the fact that many Japanese toilets are squat toilets (and your entire naked butt would therefore be visible), but also to do with the fact that, once inside a toilet, you’re meant to NOT EXIST.

One of my fellow exchange students had noticed this four years earlier when I was on a different, high school exchange program in Yokohama. She called goodbye to her host mother one morning before trotting out the door to school but the host mother was nowhere to be found. Had she slipped and fallen? Worried, my New Zealand friend went looking for her host mother.

The host-mother was in the toilet (with the door closed, of course). Why hadn’t she hollered back? Later, after returning home from school that same day, my New Zealand friend caught a tongue-lashing from the Japanese woman, who believed it the height of rudeness to chase someone down to say something to them when they’re in the toilet. In Japan, if someone’s in the toilet, they are dead to you.

This has something to with Shinto and cleanliness, I don’t remember it was ages ago.

Anyway, if you’re ever in Japan, don’t stride into a public toilet area and start yakking to someone at the mirror, as often happens in Western women’s toilets. Worse, don’t even think about chatting to your friend/family member through the closed toilet door. You will put every other patron off whatever they’re trying to do in there.

In a bid to overcome a general reluctance to pee and poo in public, the fancier Japanese toilets make a tune when you’re tinkling so others nearby can’t hear your flow. Without that feature, Japanese will flush constantly instead, wasting a lot of water.

We are at our most vulnerable when we’re expelling, and this is not only a Japanese issue. Most people, I suspect, would be somewhat familiar with the wish to poo in private if possible, especially people acculturated as women.

But it makes sense that toilet horror naturally makes its way into Japanese urban legend.

Urban legends are contemporary forms of folklore that are often used to provide lessons in morality or explicate local beliefs, dangers or customs.

Another allure of horror is relevance. The audience finds some kind of relevance in the film, whether it can be universal like the fear of death, the unknown, or cultural, social, religious relevance. For example, South Korea is a highly competitive country and is the one of the top countries with the highest suicidal deaths. Because of strict studies in middle school and high schools, many students commit suicide by falling off of the rooftop of their school. There are many films with young girls coming back to haunt their enemies with long black hair and pale skin—a highly profitable film genre due to its social relevance.

The Aesthetics and Psychology Behind Horror Films

The most famous of the Japanese ‘toilet legends’ is “Toire no hanako-san“, or “Hanako of the Toilet”. A girl dies in the school toilets (because of a WW2 bombing, or because she suicided etc.) Now she haunts the toilets. Your classmates can summon her. The stories vary, in true urban legend style. Each school has its own.

At the other end of the privacy spectrum are not Western countries, that’s for sure. My fellow Chinese exchange students that year in Kyushu told me how they’d been toilet trained in kindergarten. Teachers lined them up in a single long row. They’d all drop their little daks in unison and hopefully pee into a small, purpose-built gutter running along the bathroom wall.

After learning this fact, I had a nightmare in which I was busting to pee but I must have been in China because the public toilet was literally a massive room with a trench (no cubicles). I couldn’t go. (I woke up busting to pee, of course.)

“HERE THERE BE TYGERS” BY STEPHEN KING

If a collectively scary thing exists in the world, Stephen King has you covered. In this case, the horror revolves around a school bathroom. Not all Stephen King work is for adolescents, but this short story would find a natural audience of 12-13-year-olds (despite starring a Year 3 student). If teaching literary terms, “Here There Be Tygers” is a readily-accessible example of the personification of a psychological state (fear personified as tiger).

It’s easy to forget how old Stephen King is. This short story was first published in 1968. So if reading this with an adolescent come 2021, there is… more to discuss.

I deduce Stephen King wasn’t a huge fan of school toilets as a student (and perhaps even when he was briefly a teacher) because there’s a horrible bathroom/locker room scene in Carrie, his first published novel. For everyone who starts menstruating around adolescence, bathroom time takes on a very clear and obvious horror: Blood symbolism and all that entails.

SETTING OF “HERE THERE BE TYGERS”

Though written in the 1960s, this school toilet feels universal. It’s not a realistic toilet block and could be in any school. It exists in an underground space, inheriting all the fear and symbolism which comes from universal conceptions of the underworld.

STORY STRUCTURE OF “HERE THERE BE TYGERS”

PARATEXT

THE TITLE

The title of this short story borrows from William Blake, who famously spelled tiger like tyger in 1794, before spelling was standardised. Blake’s poem compares a tiger to fire (the orange stripe thing works nicely) and wonders how God can come up with a scary tiger and then make a lamb. What the heck. How? What kind of anvil does God need to make both of those COMPLETELY DIFFERENT creatures? (Blake thinks of God as a blacksmith, which you would, wouldn’t you, if you lived through the 1700s? And isn’t everything made with anvils?)

Anyhow, from what I can gather, the spelling of Tyger is the only aspect Stephen King borrowed from Blake for this short story, along with a bit of Blake’s gravitas I suppose, in the quest to create a story which links a contemporary fear to our ancient past.

But actually, the grammatical construction of this title is more interesting than the spelling of tyger. The grammar comes from Medieval cartographers who would write, “Here there be X” when creating their maps. The X was always some scary thing.

Aside from King, other writers have made use of this sentence construction.

- Here There Be Monsters a 2018 short film

- Here, There Be Dragons by James A. Owen

- Children’s author Jane Yolen has written a series of five books, all starting with “Here There Be” in the title. (Dragons, Witches, Unicorns, Angels, Ghosts, ftr.)

RAY BRADBURY’S HERE THERE BE TYGERS

Ray Bradbury used this exact title before Stephen King did, back in 1951. In Bradbury’s short story, prospectors from Earth go by rocket ship to a distant planet to see if it’s any good for harvesting resources. They find paradise, but the planet preternaturally knows what everyone wants, which is horribly disarming to them. The all-male crew returns to Earth and reports a hostile environment.

It’s an icky story to read if you know female objectification when you see it, because Bradbury constantly compares this paradisiac planet to a woman who gives up everything she has (The Giving Tree, but for adult men), with the idea that she (the planet) must be doing all this for some kind of creepy, manipulative, entrapment purposes.

Bradbury’s story was too expensive to shoot for The Twilight Zone. I’m glad about that. But a Russian company adapted it for short film in the late 1980s and added a woman to the cast, a love interest, which is an excellent example of how ‘add a woman and stir’ doesn’t fix gender issues.

If you really want to hear it, you may be able to unearth the BBC dramatization of Bradbury’s short story somewhere e.g. on YouTube. “Here There Be Tygers” was broadcast 2011.

What about Stephen King’s short story of the same title? Any gender issues here?

Well, yes, and not because the woman dies at the end. (Men die all the time in stories.) More on the misogyny below.

SHORTCOMING

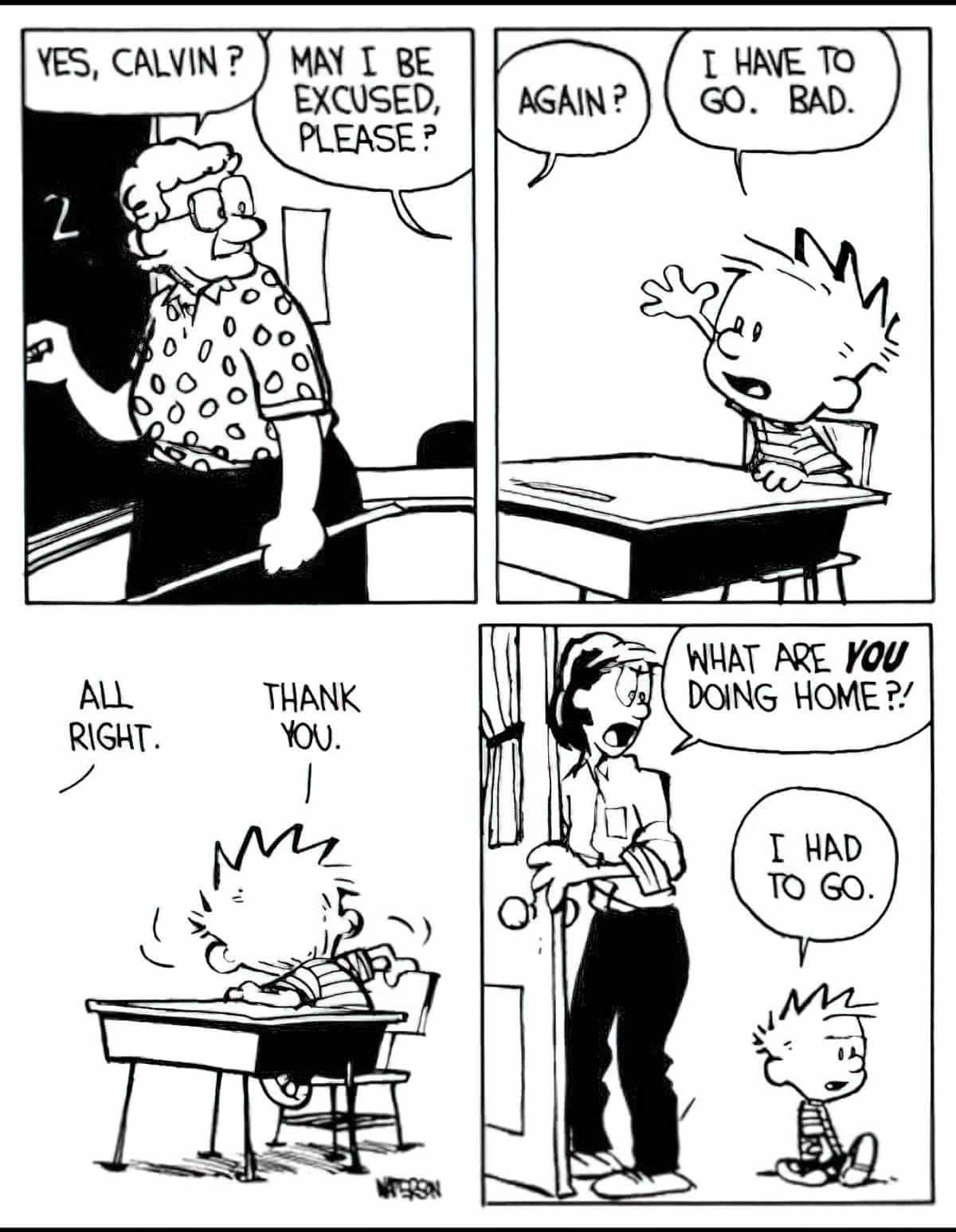

The main, viewpoint character of “Here There Be Tygers” is a child. He is stuck in class at his school but needs to use the toilet. He’s left things a bit late because he requires permission to leave from the teacher. He’s about to pee his pants if she doesn’t let him go.

DESIRE

Surface desire: To use the toilet

Underlying desire: To feel safe in his school and avoid humiliation. This story is basically about humiliation. It’s also about breaking away from the surveillance of women on the journey to becoming a man.

OPPONENT

Like any good horror story, there are two layers of opposition here, one from the everyday human world (the teacher), the other from the supernatural world (the tyger).

King encourages us to interpret this tyger as a figment of the boy’s fear. Fear can be as influential on behaviour as any real creature.

THE TEACHER

Why, in storytelling, are middle-aged women so frequently utilised as shamers, specifically for bodily function? I’m sure Bakhtin would’ve had something to say about this. Mikhail Bakhtin was a Russian philosopher and literary critic whose work only came to prominence in the 1960s, decades after he died, and by no coincidence, around the time Stephen King wrote this very story. This is not to say that Stephen King necessarily read Bakhtin. Big Ideas have a funny way of entering the collective consciousness and influencing artists anyway, hence Modernism exists in art, in which Einstein influenced artists even though the artists probably were not reading his theories.

Specifically, Bakhtin wrote about the Bodily Principle, which describes our idea of the body as grotesque. Even our own bodily functions gross us out. Gross out books are popular with middle-grade audiences (for a very short, specified developmental period) because as (privileged, able-bodied) children we move from being cared for to caring for our own bodies, claiming them as our own.

I can think of numerous young adult stories in which the mother finds the son’s sheets and the son is embarrassed that she’s anywhere near them. A particularly icky scene which springs to mind: Clay Jensen’s mother of the TV adaptation of Thirteen Reasons Why (an icky franchise for many reasons which I won’t get into here, but none of my reasons are to do with the treatment of a difficult topic in YAL). In one episode, Clay’s mother refuses to let him wash his own sheets when he clearly wants to shove them into the washing machine himself. (Ah yes, it’s been written up as a trope at TV Tropes.)

I’m not sure if the actor who plays Clay’s mother in the Netflix adaptation of Thirteen Reasons Why meant to eroticise the shame of her teenage son, or if she was told instead by the director to simply shame him or maybe do something cute, but that’s how the laundry scene comes across to me. Likewise, the mother-stand-in teacher of King’s “Here They Be Tygers” takes equally problematic delight in shaming this boy, in a highly uncomfortably erotic way. (In Stephen King’s case, I am 100% sure that’s exactly what he meant to create.)

Note that these women aren’t real; they have been created by adult men.

So why do men write women like this? I believe it comes down to the discomfort men feel, sitting with the masculine societal requirement that they be grown, strong providers but were also little boys once, who needed round-the-clock care. They once needed their mothers (it’s almost always mothers) to toilet train them, and to clean their male equipment, change their nappies and so on. Mothers can sometimes have a hard time stepping back around adolescence, and I’m sure that’s part of it too. Even if she steps back just fine, it’s so often the mother managing the household, washing the sheets, vacuuming under the beds, knowing exactly what’s going on in every room of the house. So the perception of middle-aged-woman interference exists, independent of reality or motherly intention.

I’m guessing that’s where stories such as this one come from. “Here There Be Tygers” is not only a narrative about the fear of school toilets; this is about a specifically cishet masculine fear of requiring care (or sex) from women yet hating to be so reliant on it. (Right across Stephen King’s stories, masculinity is a big theme. However, he frequently fails to encourage reader critique of the toxic status quo.)

PLAN

The boy of “Here There Be Tygers” is pretty limited in what he can ‘plan’. Like any kid in school, he’s hemmed in: fully timetabled, heavily supervised. This fact of childhood (and high school) is tackled most frequently by children’s book authors, who frequently kill off the mothers or otherwise whisk caring but interfering adults out of the way.

The main characters of classic cosmic horror are equally constrained, and equally without backstory. This boy is an archetype — he is supposed to be all of us, anyone who ever went to school and needed to use those big, scary toilets. This character is also, very specifically, a boy child, though when it comes to specifically boy children written by male authors, I’m not always convinced they realise they’re writing anything other than a universal human.

THE BIG STRUGGLE

The first battle is between the boy and his teacher and her clear wish to humiliate him in front of his peers. she insists on using the word ‘urinate’, and cutesy names for bodily functions exist in language for a reason. The medical terms somehow make the function sound more disgusting. (I’m sure there are solid phonological reasons I am yet to investigate.)

Then there’s the tiger in the toilet, of course, and the whole death scene.

ANAGNORISIS

King has tricked us. He’s persuaded us that this tyger is a personification of a boy’s fear, but the big reveal: The tiger is real!

NEW SITUATION

We don’t find out what happens after the death but the boy arrived to us in statu nascendi, which influences how much we expect to know after the battle and anagnorisis part of the story. (We expect much less about what happens at/after the end when we don’t care about a character as an individuated entity.)

EXTRAPOLATED ENDING

You could read this story another way. Maybe the boy sees himself as harbouring a tiger within — his own inherent violent streak — and it is the boy himself who kills his teacher in the toilet, We Need To Talk About Kevin style. Grim.

I prefer the reading where the killing of the teacher is a masculine overcoming of fear-of-mothers and their bodily interference, in the journey to becoming a socially accepted man. This is a particularly misogynistic reading because he only overcomes his fear by literally killing off the woman, but honestly, this text presents its misogyny on a platter.

RESONANCE

The 1960s was the Wild West of schooling, when larger, more anonymising schools existed but before anti-bullying initiatives were in place, long before the Zero Tolerance policies against violence and harassment. This was the era of “Sort it out between yourselves”, of corporal punishment dished out lightly. Even though schools aren’t like that anymore, today’s school toilet blocks are barely less scary. Take the TikTok bathroom trend of 2021, which made it to my own teenager’s high school.

My own (Australian) teenager’s high school recently sent an email to parents asking for information about vandalism which took place in the boys’ toilets. Someone removed the cubicle doors, causing several thousand dollars worth of damage.

The same email explained that this is part of a 2021 Tiktok challenge in which students vandalise their school then post the video on the social media platform for likes.

Even more ominously, another 2021 Tiktok challenge required students to physically assault their teachers, and too many took up the challenge. Stephen King could never predict the emergence of Tiktok when writing this story back in 1968, but the ending of “Here There Be Tygers” reads a little differently after considering these TikTok trends, no?♦

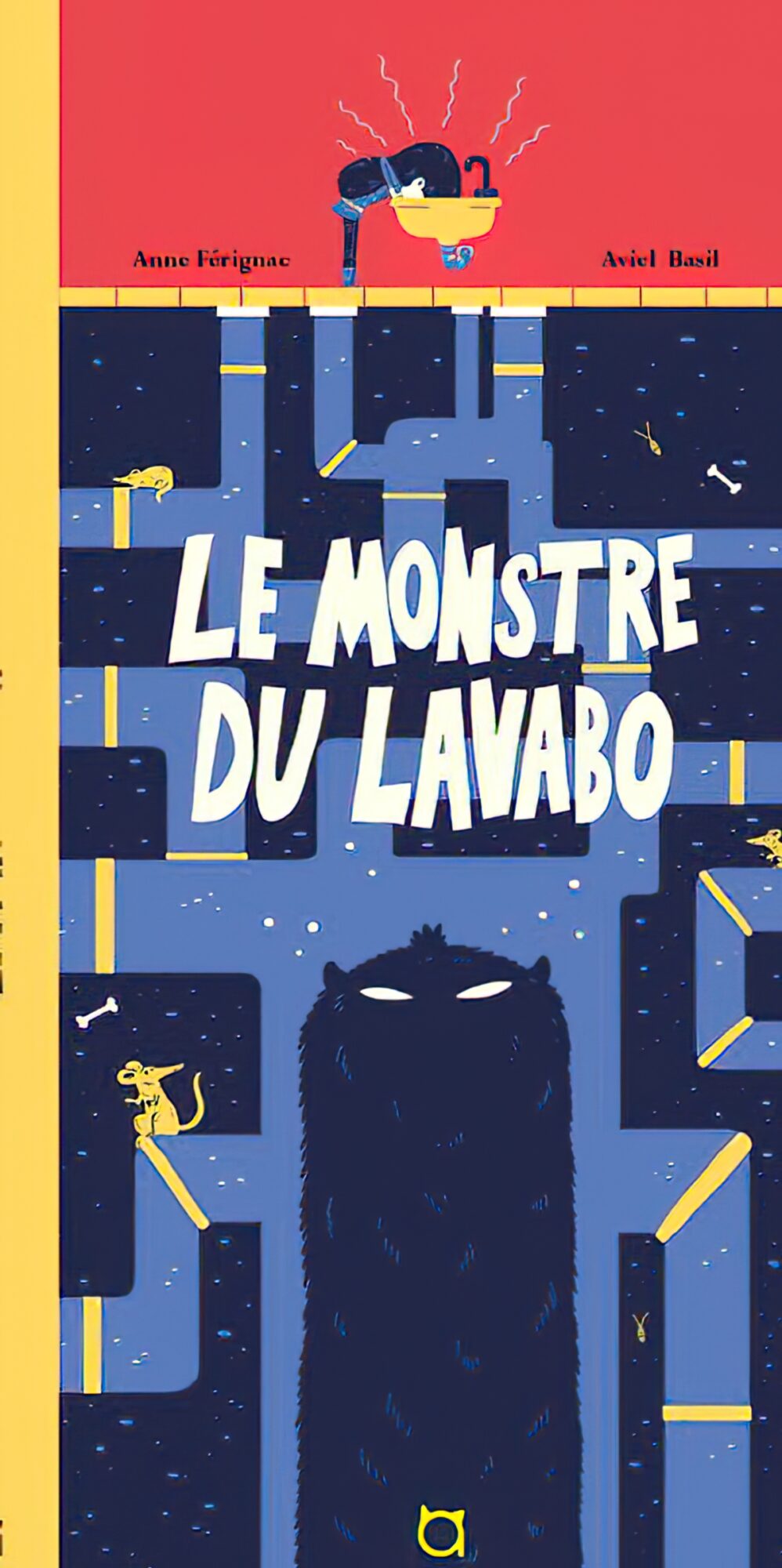

TOILET HORROR IN CHILDREN’S LITERATURE

Toilets, bums, farts, poo… It’s all part and parcel of children’s humour.

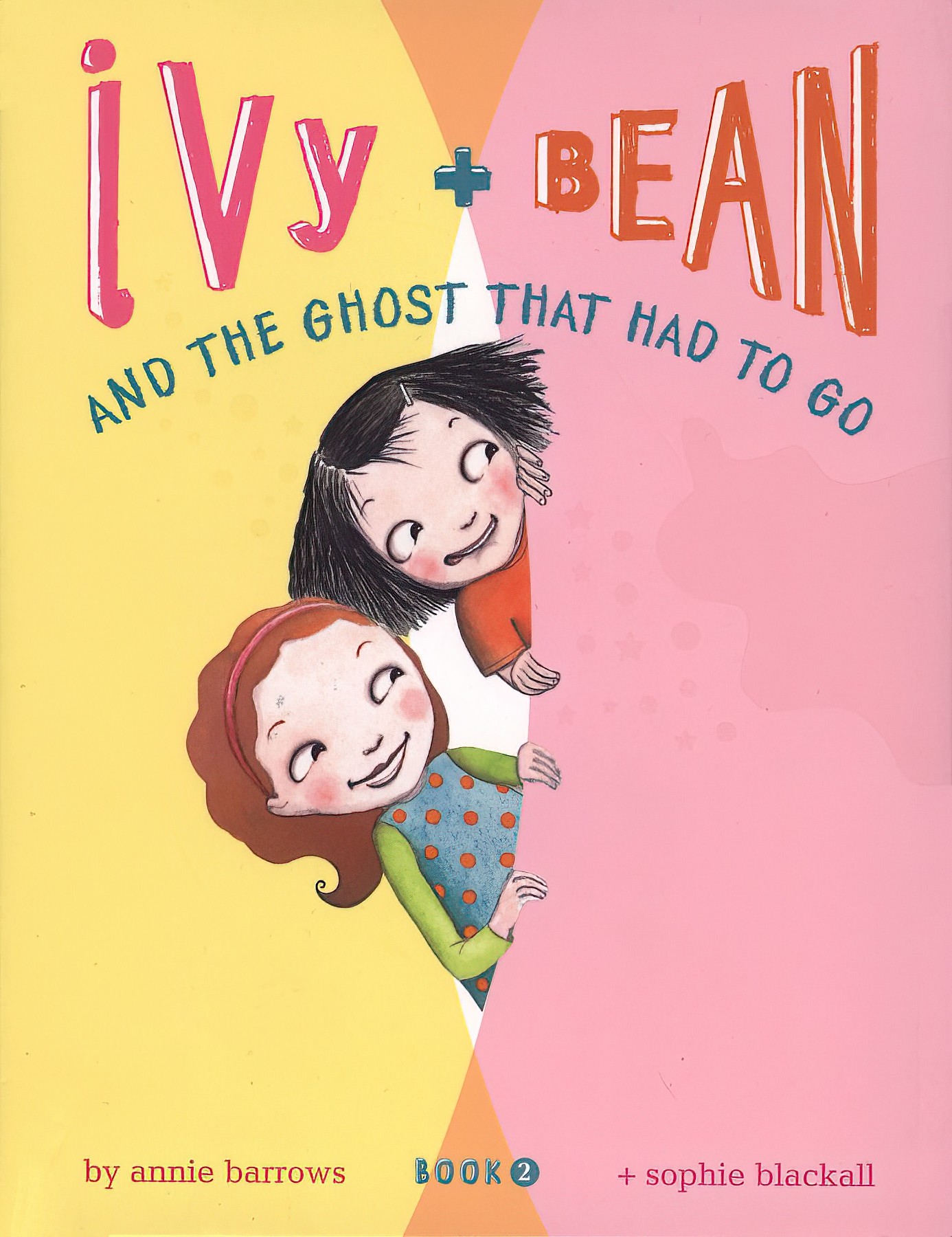

Ivy + Bean And The Ghost Who Had To Go is an Ivy + Bean chapter book about a legend which takes off in a school when someone starts a rumour that, you guessed it, there’s a ghost in the girls’ bathroom. Note the pun in the title, which speaks to the cosy vibe.

Plumbing in general is scary. First your poo is there, then it’s not. Moreover, as it disappears, cistern water makes a freaky, loud gurgling sound. We don’t know where it goes or what’s down there. Could be a monster’s stomach. If you sit on the toilet while you flush, maybe you’ll be sucked down with the poo. (A genuine childhood fear of mine.)

BATHROOM FEAR IN STORIES FOR ADULTS

In adult film, bathrooms are frequently a place where characters try to rid themselves of trauma. Underwater scenes of all kinds can be linked to fear of the bathroom as well.