Conflict, conflict, conflict. Writers seeking storytelling advice are constantly bombarded with the message: Every story needs conflict; nay, every scene! But is this really true? When advice-givers say ‘conflict’, what are they really talking about?

Successful stories don’t need conflict… if conflict means arguing, wrestling and wishing each other dead.

Stories need opponents.

Here’s the thing about opponents: An opponent can be someone you love. An opponent can love you hard, right back. For the purposes of a story, two characters only need to want different things. This turns two loving characters into natural story-worthy opponents. Opposition is unrelated to kind intentions.

I recently listened to an interview with Rutger Bregman, promoting his new book Humankind: A hopeful history. Despite much evidence to the contrary, Bregman would like to remind us that humans are wired for kindness.

It’s very hard to write interesting fiction about good people, right? There’s this saying from Tolstoy, the Russian author, who once said, “Every family is happy in exactly the same way, while every unhappy family is unhappy in a unique and peculiar way”… It’s just hard to tell good stories about people who behave decently… The good is often pretty boring. It’s one of the reasons why I write about Lord of the Flies in my book.

Why has Lord of the Flies become such a hugely influential novel? Well. Partly because it’s just exciting. Kids love reading about kids on an island who behave in a really terrible way. So that’s at least part of the reason. I could think of other reasons as well. It’s deeply embedded in Western culture, this notion that humans have evolved to be… selfish, deep down. One scientist called Frans de Waal calls it ‘veneer theory‘: Civilisation is only a thin layer. Below that lies raw, human nature. This idea comes back again and again and again.

Rutger Bregman in interview

Bregman does not like veneer theory, observing that the stories we tell ourselves are the stories we become.

This is why we seek out kindness in children’s books. Even the most pessimistic person can mostly believe in the goodness of children as tabula rasa, and the potential for children to grow into decent adults if exposed to kindness.

If it’s very difficult to write interesting fiction about good people, and children’s authors are doing just that, then children’s authors must be among the most accomplished writers out there.

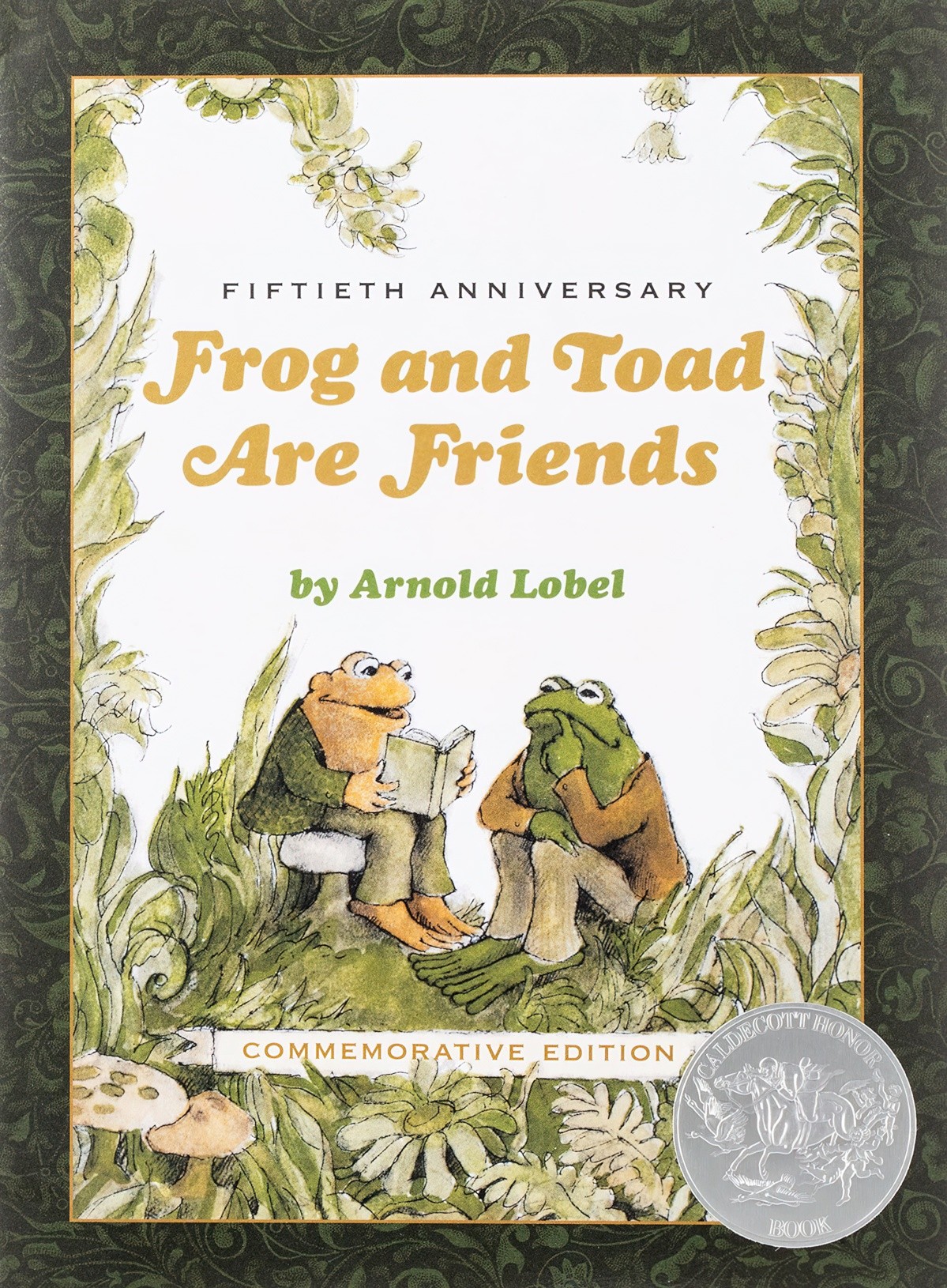

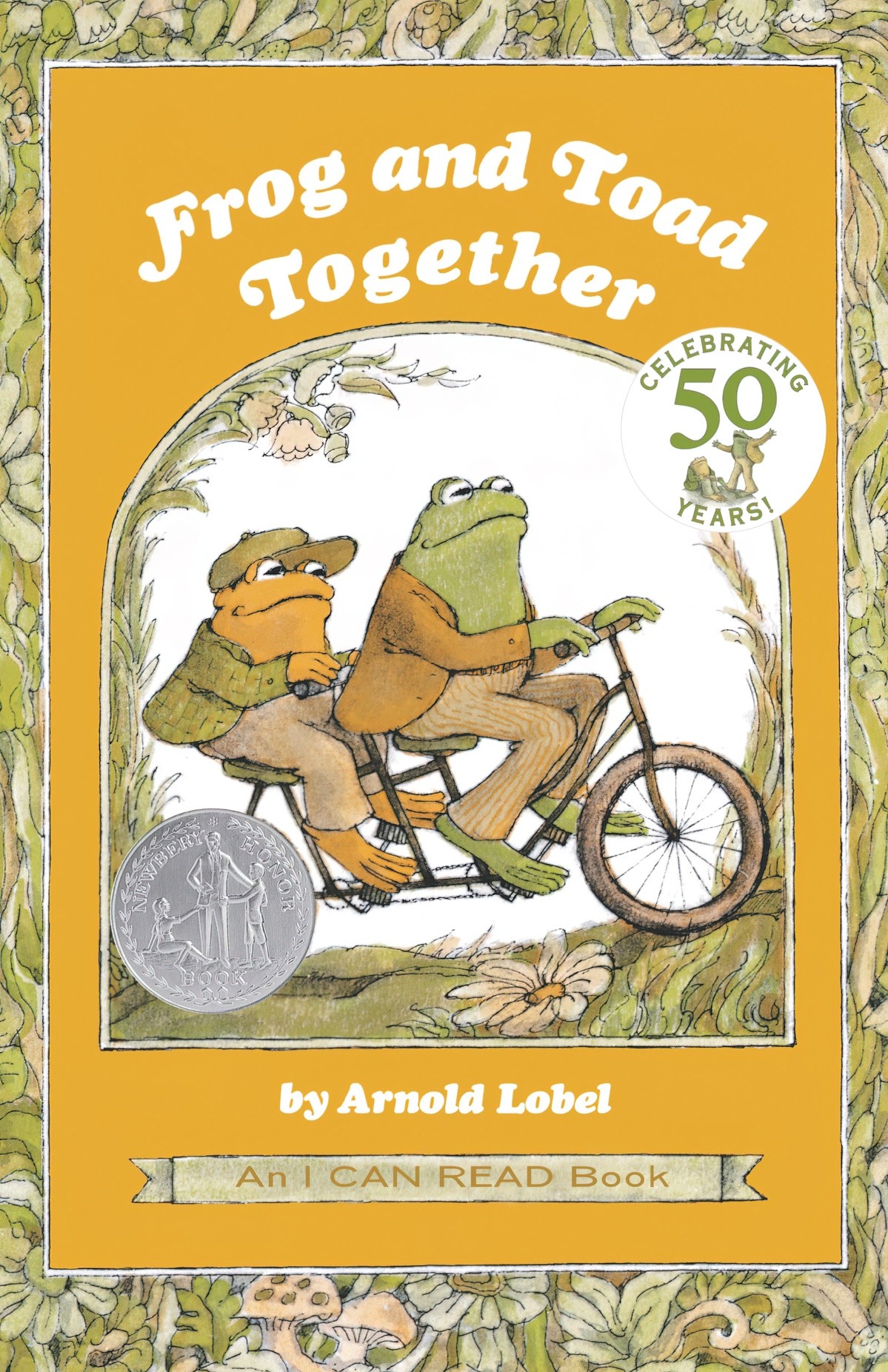

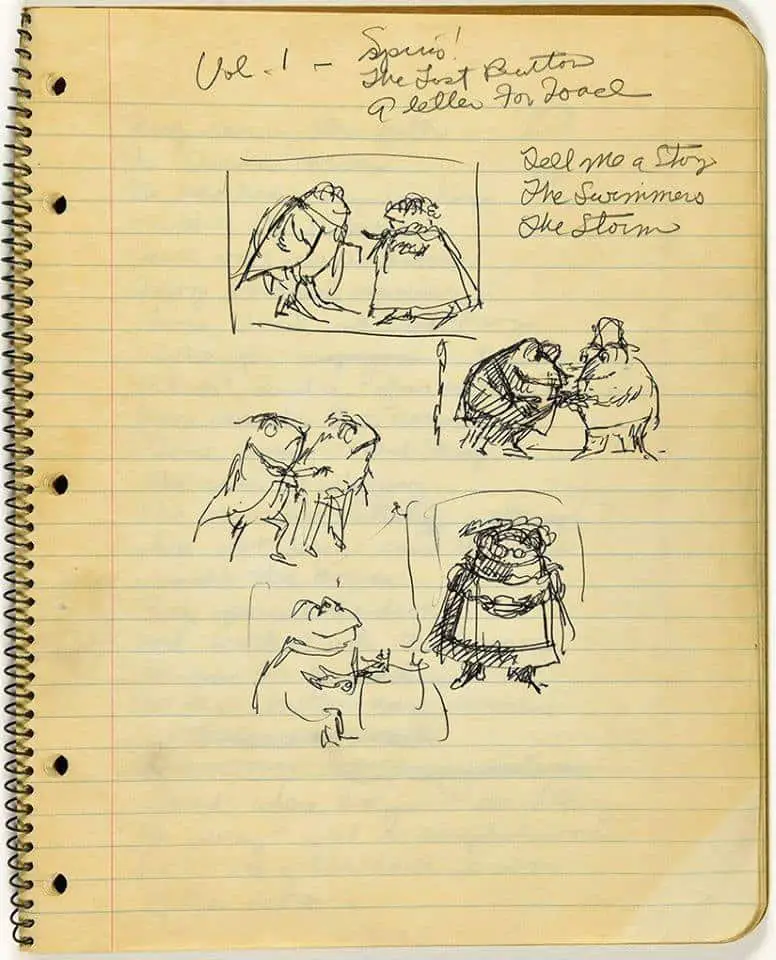

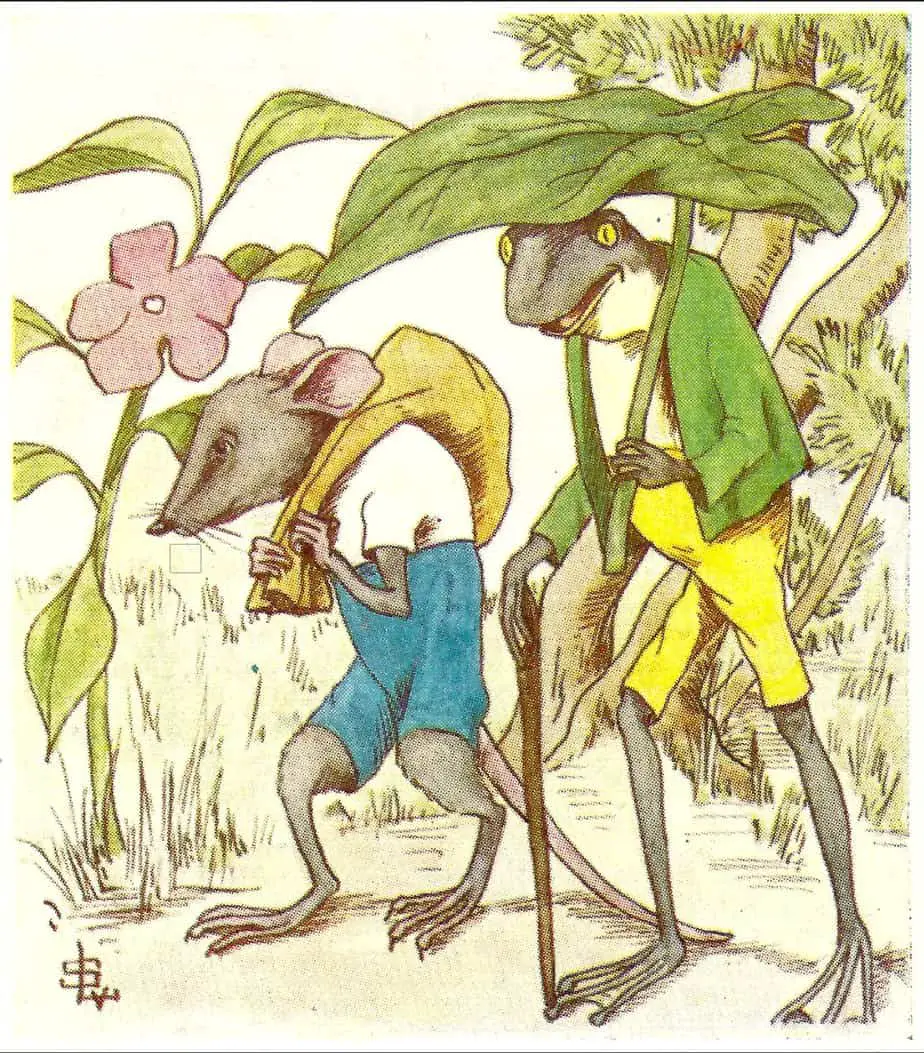

Let’s take a close look at a series renowned for its kindness: the Frog and Toad early readers by American author and illustrator Arnold Lobel (1933-1987).

The Frog and Toad stories were published between 1970 and 1979.

THE STORY WORLD OF FROG AND TOAD

Some time ago, “The Rules of Road Runner” were made public. I was a big fan of Road Runner as a kid, so it was interesting to see the guidelines which guided the creators. Riffing on that, here are what appear to be Arnold Lobel’s rules for my favourite early readers: Frog and Toad.

- Frog and Toad live in a utopia similar to that of The Wind In The Willows. Characters don’t worry about money or food. As in any arcadia, every life necessity exists in abundance. Characters worry instead about threats from unknown opponents who live in the ‘forest’ around them (actually hills, a swamp, meadows, a river and woods). And because they don’t have to worry about money or food, they are freed up to worry about other things, such as a lost button. This describes the well-cared-for child experience of the world. (I never worried about food; I worried terribly about what I’d do if my shoelace came undone with no one around to tie it up for me.)

- Though Frog and Toad are of proportional size among their own small cast of characters, Lobel gives us the feeling that there are creatures out there far bigger than they are. Readers have a few clues about this: Grass grows tall as trees. Frog tells a story about a giant frog (who looks exactly like himself dressed in a sheet).

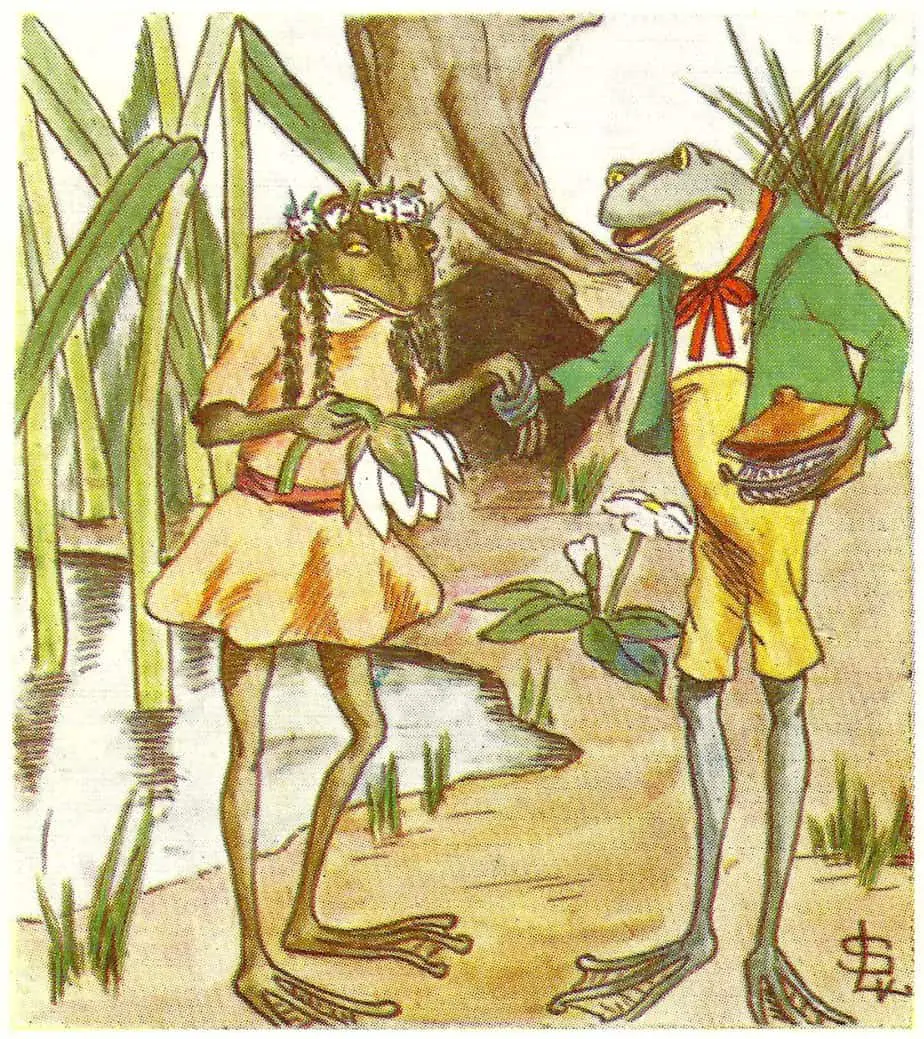

- Frog and Toad dress like early 20th century country gentlemen living in genteel poverty. (Toad’s bathing suit is from the 1920s.) Neither Frog nor Toad ever wear shoes, which helps to remind readers that they are amphibians, not just humans with weird, warty heads.

- There are no humans in the stories. The reader never knows if the animals are speaking like humans to each other, or else using a kind of animal talk.

- The ‘forest’ is a symbolic forest, if not an actual forest. Bad things lurk in there à la The Hundred Acre Wood. If fearsome creatures appear, it turns out they are not monsters at all. This plot is reminiscent of Winnie-the-Pooh (e.g. The Worzle.) The reader is left with the impression that everything terrible is imaginary. (The emotional content of Frog and Toad is reminiscent of A.A. Milne and I’d wager Milne was a strong influence on Lobel.)

- There are four distinct seasons in this world. Along with other cultural signifiers such as the summertime tradition of eating ice-cream, or cookies in the home in front of a hearth, a Christmas tree in December, the Frog and Toad world is a take on northern USA.

- The colour palette is limited to muted greens and greys, reminiscent of the murk of a pond. The original books were printed with separations. Arnold’s daughter Adrianne (also an artist) explains that her father made the muddy brown out of red and green. He also muddied the green by mixing bright colour together. In this way, even Lobel’s colour mixing is symbolic in that it relates directly to Frog and Toad, who appear ‘muddy’ on the outside, but who in fact comprise bright, beautiful colours underneath.

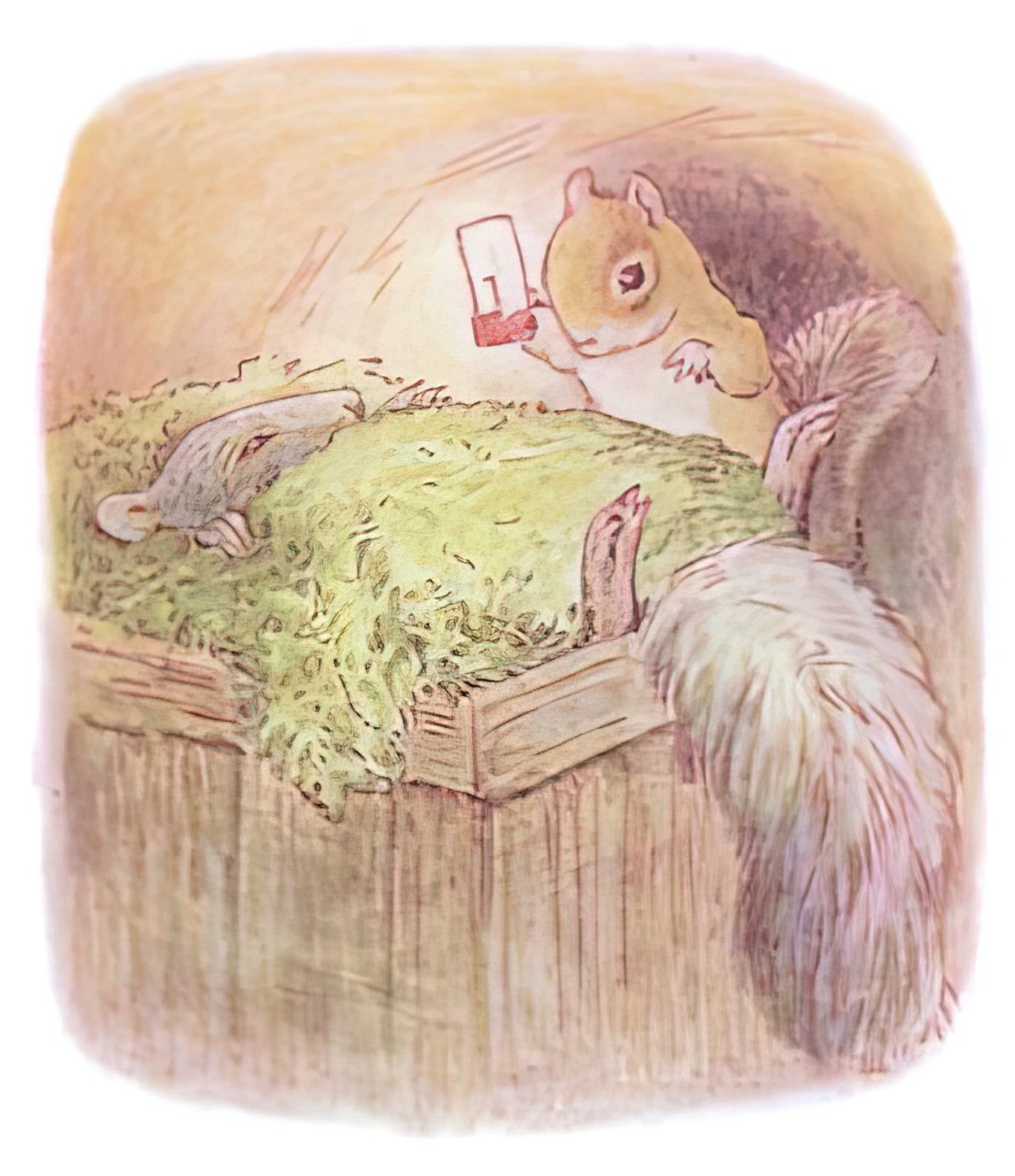

- Frog and Toad are adorable but not cute. As an interesting contrast, Beatrix Potter was one of the first author illustrators to create a lovable main character out of a frog. Because it hadn’t been market tested, her publishers were not confident readers could ever fall in love with Jeremy Fisher. So Beatrix Potter went out of our her way to make the illustrations of Jeremy Fisher as beautiful as possible. By the time Arnold Lobel deliberately created a murky palette for his Toad and Frog illustrations, Beatrix Potter had proven to the world of publishing that readers can indeed fall in love with amphibians. Morever, Lobel showed that readers can fall in love with amphibians even when they are not ‘pretty’. Lobel’s unpretty frog and toad are a deliberate subversion on the assumption that we need to go out of our way to appeal and appease (aesthetically and otherwise) before we are deserving of love. Lobel teaches us that we are all deserving of great love, no matter what we look like or how useful we are to other people. We only need to be kind.

- On a spectrum of anthropomorphism (from completely animal to completely human but in an animal’s body), Frog and Toad are near the fully anthropomorphised end, meaning we code them as (almost) fully human. In these stories, Lobel rarely draws our attention to the fact that they’re amphibians, not men, and when this is done it is subtle, and for comic effect e.g. Toad looking ‘funny’ in a swimming costume. However, the young, emergent reader won’t necessarily get the layer of the joke where toad looks funny because he’s a water creature wearing human clothing. Stories have a layer for children and a layer for adults, which children may or may not get.

- Other animals are less anthropomorphised than Frog and Toad, our main characters. Other animals don’t wear clothes and live in animal homes such as bird nests.

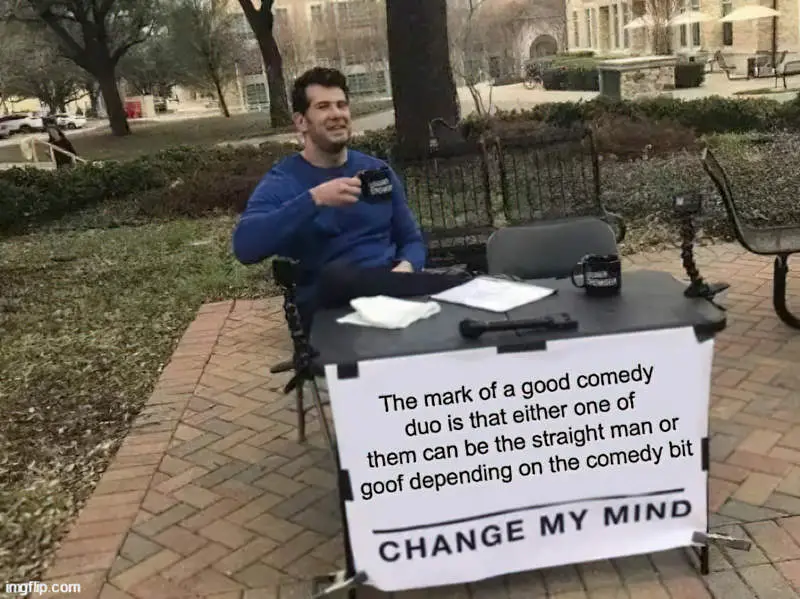

- To use comedy terminology, Toad appears to be the straight guy, with an occasional depressive streak. Frog is bigger in size and more happy-go-lucky. However, the line between funny guy and straight guy isn’t a clear and strict one. Their relationship is more balanced, as good friendships always are. Lobel seems to go out of his way to balance the friendship.

- Like Sesame Street’s Ernie and Bert, another pair of masculo-coded characters who share their lives together, Frog and Toad are on-the-page friends. If Frog is there when Toad wakes up, it’s clear the pair have not slept in the same room; Frog will be looking in through the bedroom window as if he just arrived. However, in line with Kenneth Grahame’s Wind In The Willows, there is a clear, queer subtext running right through a number of these stories, legible to anyone ready to find it, but otherwise hidden.

- Because these are early readers, vocabulary is limited and sentence structure is simple. But because adults read early readers alongside their young children, the best early readers are truly dual audience. Each Frog and Toad story carries a universal message which applies to all ages.

- Meaning: each story has two layers: a narrative layer (the plot) and an aesthetic layer (thematic).

- The narrative layers (the plots) are plentiful across the corpus of children’s stories. But Lobel’s aesthetic layer is specific to the Frog and Toad story world.

- The aesthetic (theme) is always friendship. Every story ends as an affirmation of the deep, abiding relationship between two characters. This friendship runs so deep that no ugliness or depressive slump or misunderstanding can break it.

‘Queer’ not as being about who you’re having sex with (that can be a dimension of it); but ‘queer’ as being about the self that is at odds with everything around it and that has to invent and create and find a place to speak and to thrive and to live.

bell hooks

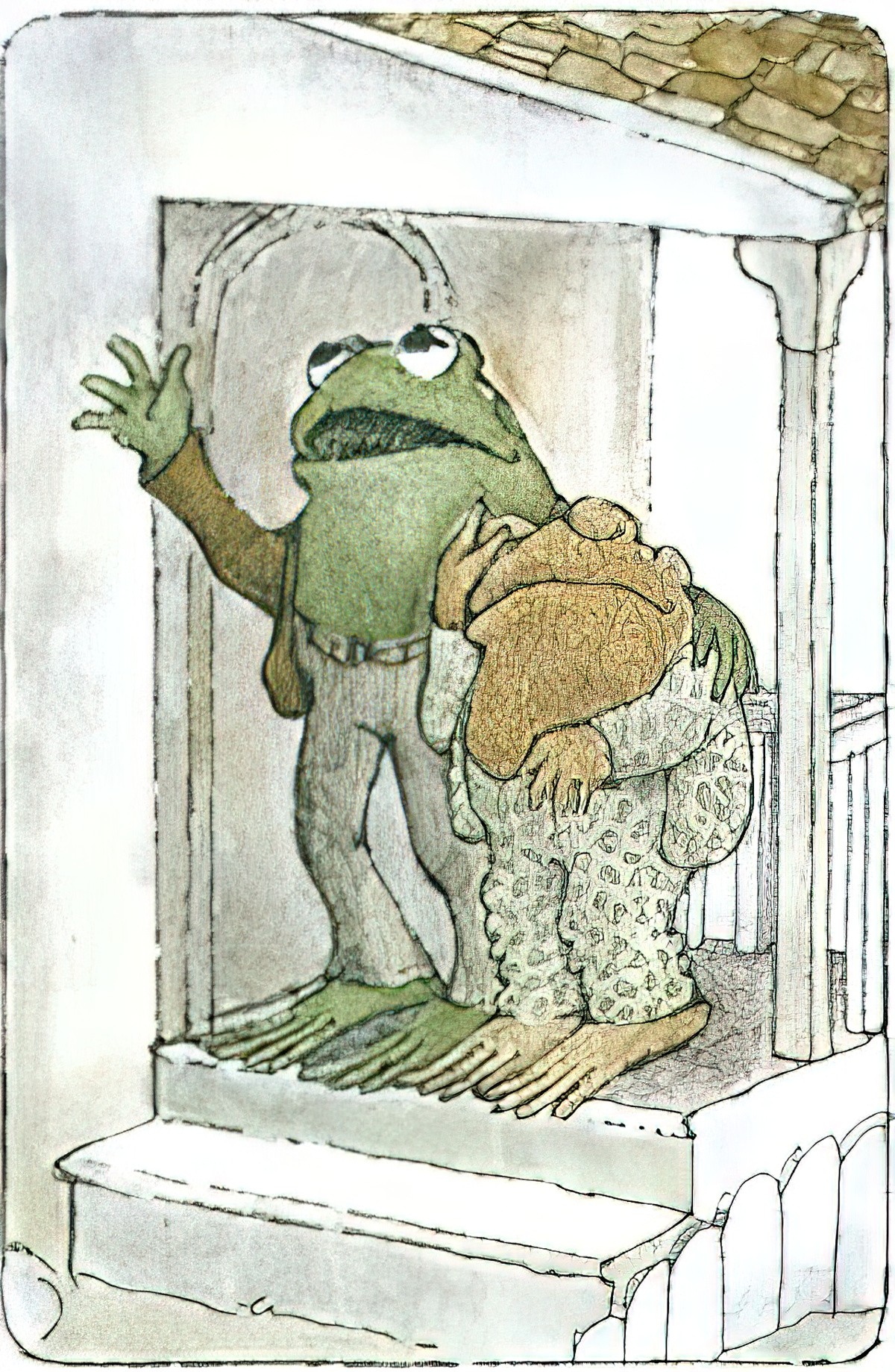

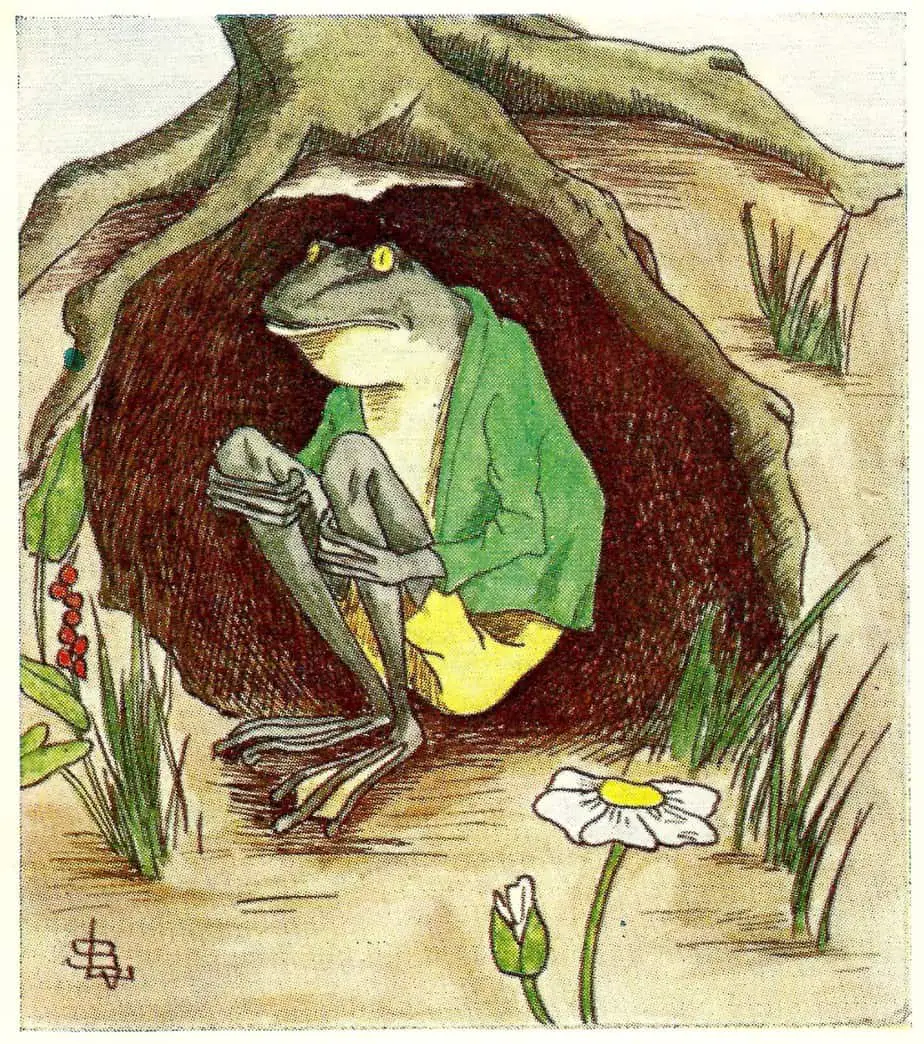

TOAD’S HOUSE

The house is a Tardis — bigger on the inside than on the outside. The ground floor has a fireplace, a chair and Toad’s bed in a corner of the room. There is a window next to the bed with opens, and a china cabinet on the wall. There’s a reading light with a pull string switch.

The porch doubles the square meterage although, to be fair, we don’t know how far the house extends left into the long grass. Quite a ways, I’d suggest.

In cartoons, don’t think too hard about the story logic of architecture. It’s part of the humour.

Toad also has a cellar, of all things. He keeps items such as ropes down there, for pulling Frog out of hypothetical holes. He also has an attic. This is where he keeps his lantern. (The second storey is not a second storey per se; it must be the attic.)

He hangs cooking implements on wall hooks rather than tidying them away in cupboards. This allows easy access to a frying pan, which can be used to whack a hypothetical baddie over the head.

Toad’s house is your archetypal picture book dream house.

FROG’S HOUSE

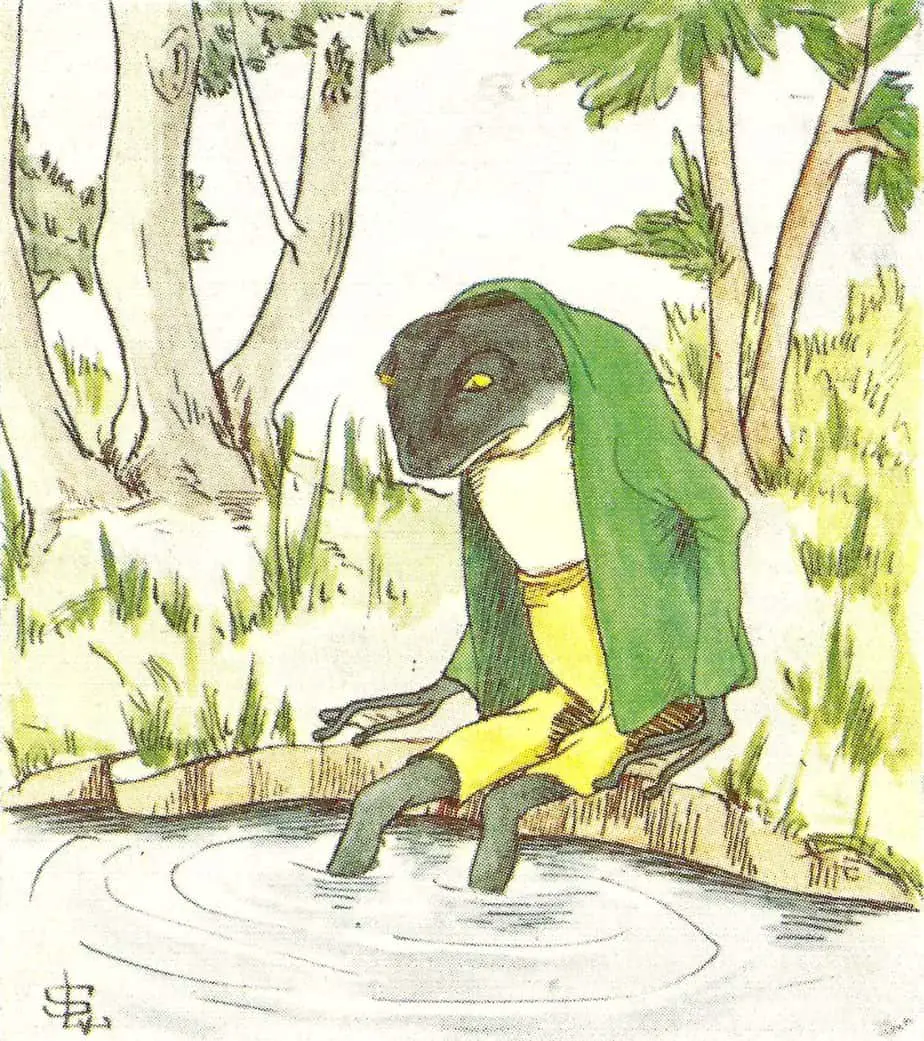

We don’t learn that Frog even has a house until “The Letter”, in which we see Frog sitting at his writing desk. I thought he might live outside in nature, more like a real frog. (After all, he swims without a swimming costume.)

Later we learn that Frog is a keen gardener, whose house is surrounded by beautiful daisies. He has a small garden shed with a rake in it, and a pergola where he seeks shade to do his potting.

In both houses, there are shutters on the windows, suggesting a storm season. We don’t see electricity or running water. These tiny houses have the amenities of the Ingalls’ settler cabin in Little House On The Prairie but with the white picket fence reminiscent of 1950s suburban American utopia.

FROG AND TOAD ARE FRIENDS

SPRING

Frog tries to coax Toad out of bed so they can enjoy spring weather together but Toad only wants to stay in bed. His excuse? It’s not yet ‘half past May’.

“We will skip through the meadows and run through the woods. In the evenings we will sit right here on this porch and count the stars.”

“You can count them,” said Toad. “I’m going back to bed.”

Frog finds Toad’s wall calendar and rips off all the pages between November and May. Trusting his own wall calendar more than he trusts his friend Frog, Toad is convinced it is May and he gets out of bed.

Until the end of the story, the reader hasn’t known what month it actually is. The final image offers a clue: There is still snow heaped on the path as the two friends go out to enjoy the weather. It would help to know how much snowfall Frog and Toad can expect over winter, but it seems to me that Frog has ripped off too many pages and it’s not yet May at all.

TV Tropes calls this Clock Tampering.

Clock tampering is the art of changing the time on a clock so that you could make time be in your favour and trick others into believing it to be the true time.

Clock Tampering entry at TV Tropes

In this case, a calendar, though ‘half past May’ suggests the calendar functions more like a clock, guiding hours rather than months, morphing time away from chronos and into kairos (fairytale time, where time doesn’t work as it does in the real world). Normally when characters tamper with a clock they are characters in a thriller or a mystery story. This low stakes story subverts any expectations readers might bring around trickery and craftiness.

After all, maybe it is actually May already?

THE STORY

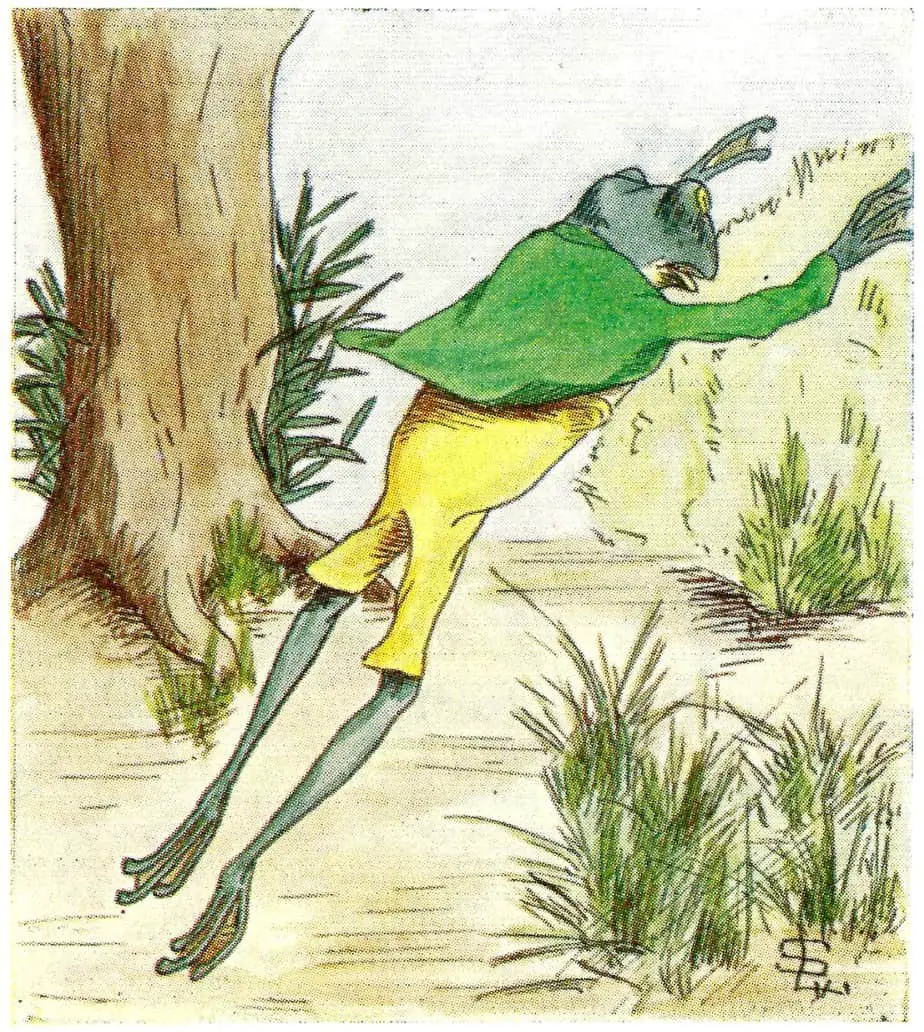

In “Spring”, Lobel introduced us to an enthusiastic Frog and a depressive (on-the-page ‘sleepy’) Toad. This makes sense given the basic differences between toads and frogs. Toads are better known for their crawling whereas frogs are better known for their leaping, which we anthropomorphise into the human emotion of enthusiasm.

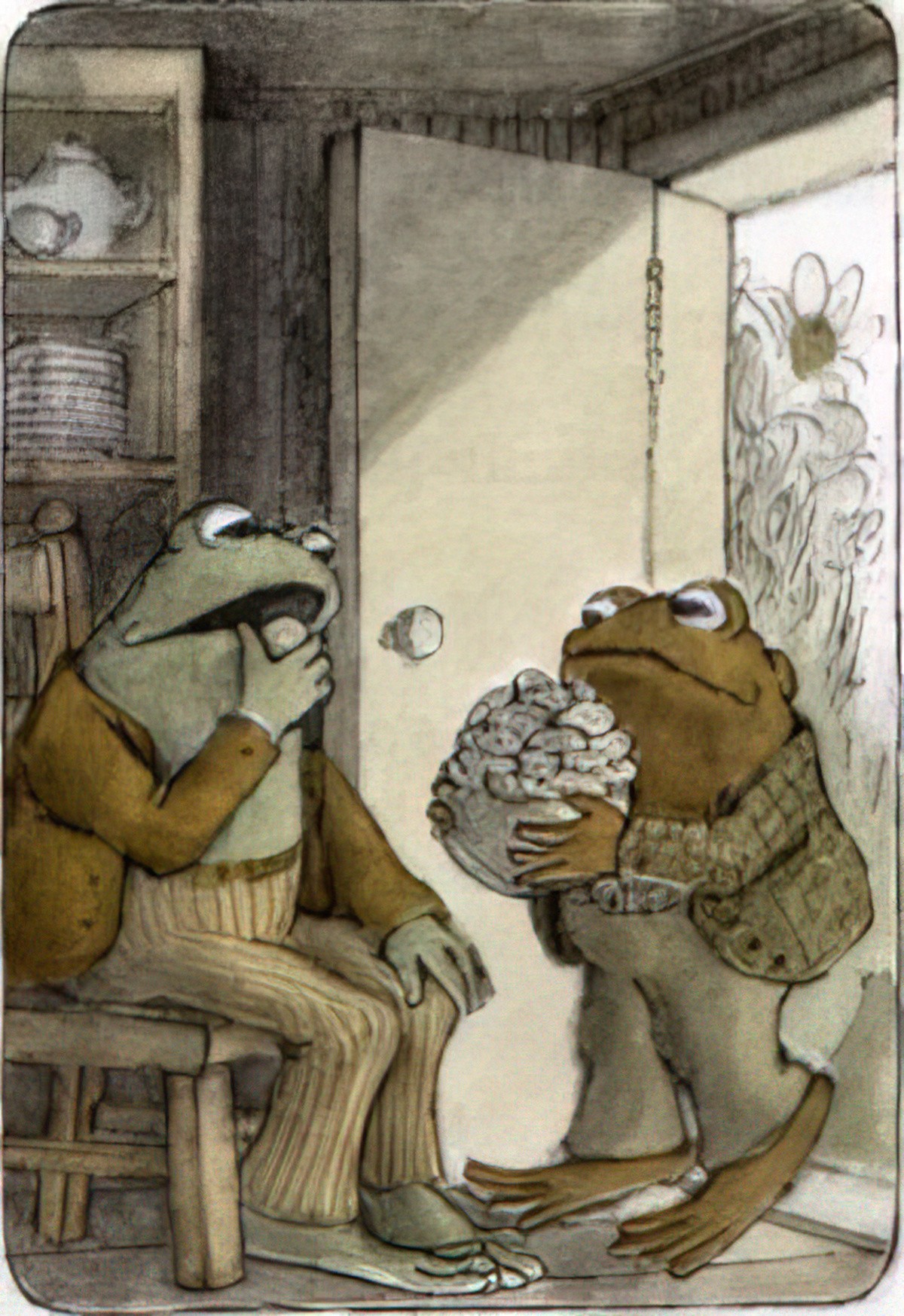

But in this next story, it is Frog who is still in bed. Toad is the one lifting his friend up. Frog is sick and is therefore ‘looking quite green’ (“even for a frog”, in case we missed the joke). It’s not clear to me that Frog is really sick, per se. I think he’s just jonesing for a cup of tea in bed, and a story. So, attention, basically.

Toad invites Frog into his own (single) bed for a rest. He sets about taking care of the supposed invalid, bringing him cups of tea and whatnot. Frog really really wants a story.

But Toad can’t think of a story. This reminds me of something I read about Arnold Lobel: Illustration came fairly easily to him, but writing was absolute torture.

I wonder if Arnold tried standing on his head, because that’s what Toad does. Next Toad pours many glasses of water over his head. Finally he bangs his head against a wall. All the while, Frog is watching on, wondering what on earth he’s doing.

Frog tells Toad he’s all better now and doesn’t need a story. But, as in the other Frog and Toad stories, there is another possible subtext: Frog isn’t better at all (if he ever was sick). He’s becoming increasingly concerned about his friend, and tells him he’s better as a form of protection.

Frog and Toad switch places because it is Toad who is now feeling sick. As in a Regency romance, throwing a glass of cold water over your head is enough to give you a deadly flu.

Now the reader gets a story-within-a-story. Frog tells a story about two good friends. This story creates a mise en abyme effect, as he is telling Toad the story the reader has just read. (He gets better at telling stories. Just wait.)

Hearing the same low-stakes story twice can be a little tedious, so the gag is that Toad falls asleep listening to it.

In this second tale, Lobel has established that Frog and Toad really do have a reciprocal caring relationship, which is what I love so much about this pair. Cishet couples in picture books so often comprise a woman (a mother figure) doing the lion’s share of the caregiving.

Beatrix Potter also wrote a story about a masculo-coded animal caring for another masculo-coded animal of a similar but not identical taxonomy. You’ll find this storyline in Timmy Tiptoes, and his caring relationship with Chippy.

This storyline is unfortunately rare in contemporary children’s literature. For one thing, adults (who buy the books) think twice about a male character inviting another male character into his bed. (This is the panic that happens when a culture hovers between full awareness but not full acceptance.)

Inevitable gay reading aside, contemporary children’s literature contains very little in the way of convalescence. Modern culture does not permit time to rest and recuperate. Go back to early 20th century children’s literature and it’s easy to find stories in which someone is sick and in bed, resting. No doubt you can think of a few modern exceptions. (There’s a Charlie and Lola story in which one of the siblings is in bed, sick with a cold.) But in general, contemporary children’s book characters go to bed to sleep, not to rest for days on end. The availability of pain medication and antibiotics has changed convalescence culture (but lets see what the 2019 pandemic does to children’s literature).

When Toad and Frog get into bed to rest, this harks back to an earlier Golden Age of Children’s Literature (earlier than the 1970s, when Lobel was writing).

A LOST BUTTON

Although this book is an early reader, constrained by length and word choice, “A Lost Button” contains the complexity of a lyrical short story, with two separate layers.

Characters losing and then finding personal items is a not-uncommon drama in children’s picture books. Another more recent example: I Want My Hat Back by Jon Klassen. In fact, all of Klassen’s hat books are about a beloved hat that someone has lost. (Across all three books, Klassen offers a parallactic reading experience: What it’s like to find something, lose something, and find something together with your friend.)

In these Lost Item stories, a viewpoint character realises they have lost something, the search begins, other characters (may) step in to offer (unsuccessful) help.

So far, so pedestrian, except for the amusing fact that Frog and Toad discover a highly improbable number of buttons which aren’t theirs, until Toad exclaims, “The whole world is covered with buttons, and not one of them is mine!” which could be a metaphor for so many experiences in life. It’s not easy to insert philosophy into a pedestrian plot, and also to make it amusing, but Lobel has done it. And, actually, when my husband lost his wedding ring, it was amazing how many of the shops at the mall he visited had a men’s wedding ring waiting for collection behind the counter, none of them belonging to him. (Men of the world: You marry with no history of ring-wearing. They are supposed to fit snug.)

Fro writers, these Lost Item plots are difficult to tie up. There has to be a surprise. Obviously, characters cannot simply find the button in a bush or something, not even after that wonderful line.

The twist: After searching far and wide, the button is at Toad’s house on the floor.

This twist is relatable, but still wouldn’t make for a satisfying ending to the story. There has to be something more, and Arnold Lobel delivers, because this is where the characterisation and theme of friendship kicks in. No matter which children’s plot Lobel uses, he brings it back to friendship, every single time. This gives him so much more to work with.

Another way of putting it: There’s a dramatic plot (searching for the lost button) and an aesthetic plot (about relating to others). Once the button is found, Lobel has tied up the dramatic thread, but he hasn’t done anything much with the aesthetic (relationship) thread yet. These are the words used by Charles May. May was talking about lyrical short stories but they apply equally to Lobel’s early readers.

Feeling bad about all the trouble his friend has gone to, Toad sews all of the other found buttons onto his own jacket then gifts his jacket to Frog.

In case you’re wondering about my husband’s wedding ring, after cleaning the house from top to bottom I finally decided to tackle Mt Washmore and put the clothes away in a cupboard, like a regular adult. The wedding ring was on the bedroom floor, beneath a pile of clean washing.

A SWIM

This one is hilarious but also sweet and relatable. Perhaps it’s more relatable for older readers than young ones, who typically have easy-to-live-in bodies and gad about naked without shame.

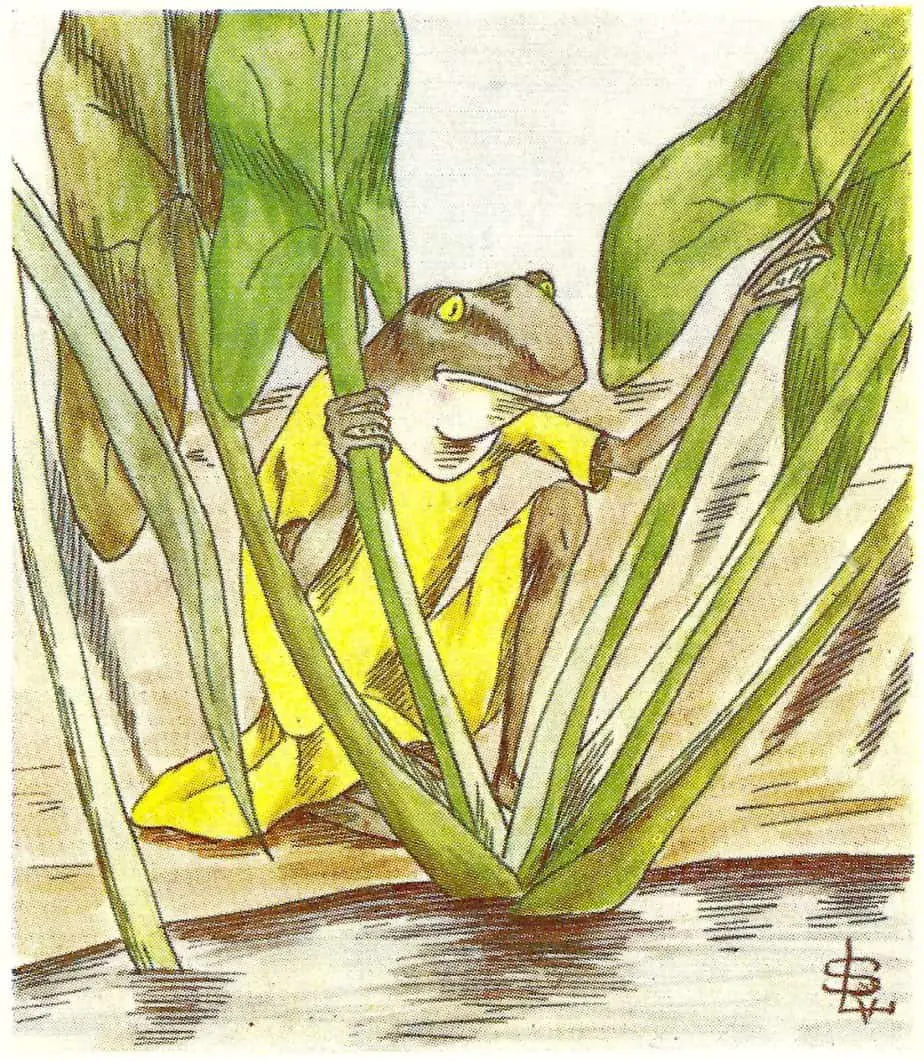

Poor Toad has a lot of body shame. He is warty and murky brown. He wants to go swimming with Frog but he doesn’t want to swim naked. So he wears a bathing suit.

This is already a genre satire: Children’s stories which star anthropomorphised animals as human stand-ins are so popular and common (thanks, Beatrix!) that they are no longer funny as spectacle (look! a frog wearing clothes!). We go about our reading lives completely ignoring the fact that Olivia is a pig, a little girl in an actual pig’s body, or whatever. There often seems no reason for this, either (spoiler: there always is, but it’s Doylist).

Animal stories are, these days, regularly spoofed by the very authors who create them. Self-spoofing. In this case an amphibian, whose natural habitat is the water, is timid about going into the water without human clothes. Zebras who wear striped pyjamas is a similar sort of gag. (In fact, Toad’s pyjamas look a lot like his greenish, warty self.) This visual humour works perfectly because it doesn’t pull readers out of the story world unless they are ready for it to, and therefore works for a dual audience (of adults and children). Meaning: if young children are fully immersed in the world, they won’t notice the ridiculousness of it.

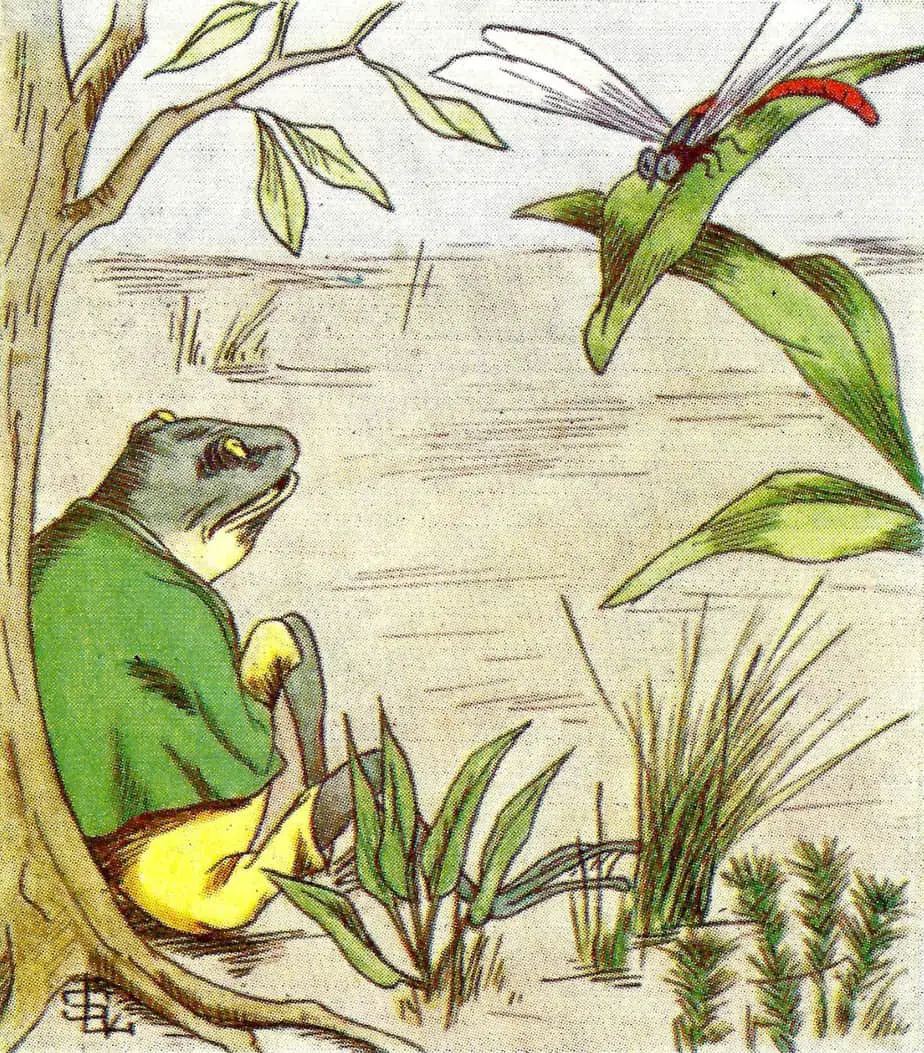

Toad agrees to get into the water but Frog isn’t allowed to look at him because he “looks funny” in his swimming costume. Other animal characters come to the water and, being a good friend, Frog tells them to go away because Toad thinks he looks funny in his bathing costume.

The various creatures decide they’d really like to see Toad looking funny in his bathing costume so they lurk nearby, waiting for him to come out.

Toad stays in the water, feeling trapped. This reminds me of a song we were made to sing at school assemblies: “Itsy Bitsy Teeny Weeny Yellow Polka Dot Bikini”. The song is about an adolescent girl wearing a bikini ‘for the first time today’, and experiencing the objectification of everyone around her. Like Toad, she stays in the water until she turns ‘blue’.

And in case you think the objectification of prepubescent girls started in the modern era, Dick Clark’s ‘joke’ about an eight-year-old in a bikini completely misses the mark for a modern audience. (The ‘joke’ rests on the naïve notion that no one watching could possibly find an eight-year-old girl in a tiny bikini arousing.)

Me: “No, queen. You come out of that water and slay that bikini right now!”

After I see the bikini…

Me: No wonder she didn’t wanna come out.

Commenter on the YouTube video

Eventually, Toad is so cold in the water that he has to come out. At this point, Arnold Lobel subverts our expectations of children’s books, which are endlessly affirming about difference. There’s a huge category of picture books in which an animal is different from all the other animals, but by the character’s actions, they earn their rightful place in the group. The worst of these stories are a product of our capitalist society. The rejected character must literally earn his place in a group by doing work. Then he is accepted.

It is very difficult to write one of ‘affirming difference’ stories without also conveying — by accident, perhaps — that we are only acceptable if we have something useful to offer the group. If you can’t look the same, you must compensate somehow.

Elmer the Elephant allows white people to talk about racism without actually talking about race. This story is pretty good as far as ‘affirming difference’ stories go, but Elmer still proves his worth to the group because he has a sense of humour. (At least he doesn’t prove his worth by having a super long trunk or something, reaching down the highest berries for the shorter elephants, Rudolph the Red-nosed Reindeer style.)

But is that what we really want kids to learn? That acceptance is conditional? That if you don’t look ‘right’ then you must make up for this difference by being useful, or even funny?

When Toad gets out of the water, all the animals laugh at him. Likewise, all the other animals laugh at Elmer the Patchwork Elephant when the rain removes his mask of grey berries in the rain. Elmer’s peers say something affirming about how Elmer is still a very valuable member of their group… because of his sense of humour. He’s useful to the group because he makes them laugh. This only reinforces the conditional nature of acceptance.

Arnold Lobel subverts this entirely. Lobel’s politics seem different, and revolutionary, because half a century later disability activists are still hard working on this: Everyone is acceptable by dint of being alive in the world. No one has to prove their worth, not by how we look, and certainly not by what we do, because some humans cannot ‘do’ anything to benefit us.

So when Toad gets out of the water, everyone laughs at him, including his best friend in the whole world, Frog, who admits to finding Toad funny in his bathing costume. Is this a tragedy? No, because the worst happened and Toad simply ‘picks up his clothes and walks home’.

In the following stories we understand that Frog has seen Toad at his most vulnerable and loves him anyway. Toad did nothing to ‘earn’ this level of acceptance. He is neither useful nor funny. He’s not even brave. Despite laughing heartily, Frog’s acceptance of Toad is the most affirming acceptance of all.

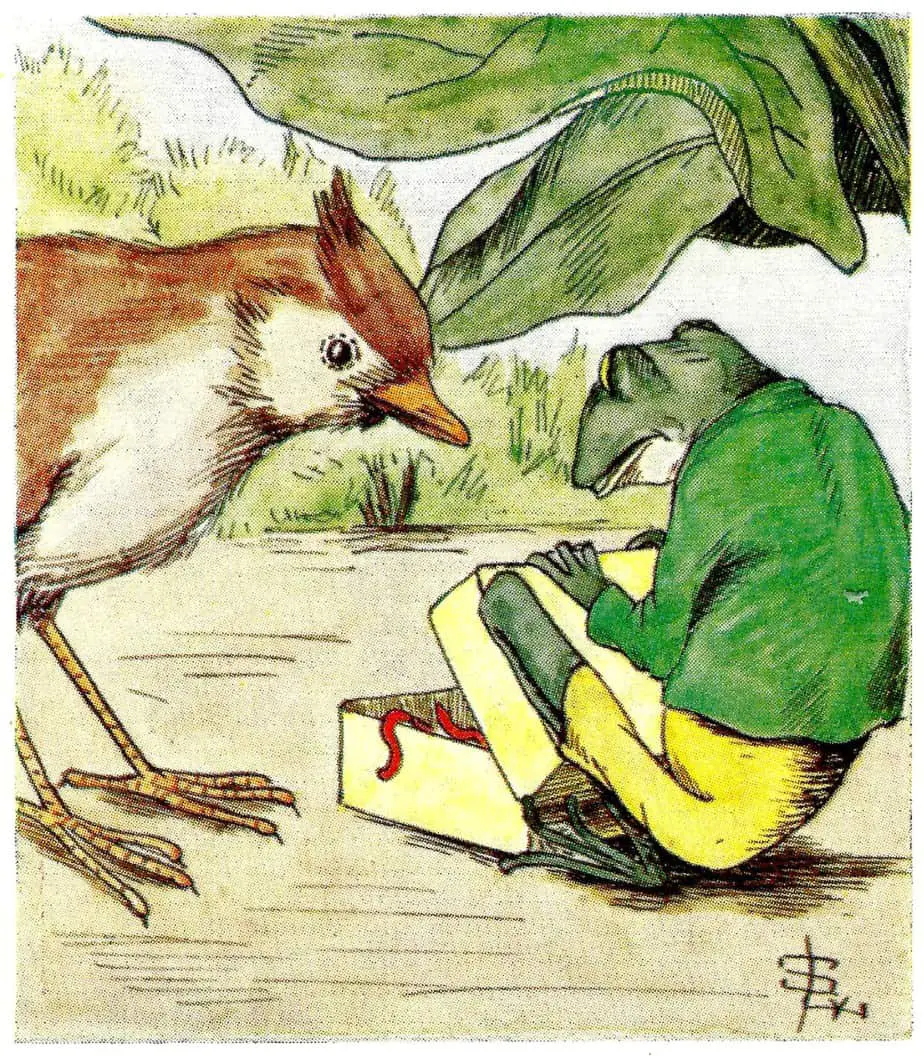

THE LETTER

“The Letter” almost counts as an antiplot.

Toad has fallen into one of his depressive slumps because he never gets letters. We never see him writing letters, either, and frankly if you don’t write letters you shouldn’t expect to get any back. It’s easy to lose a bit of patience for Toad. (Readers generally don’t have much patience for characters with no oomph.)

However, characters such as Toad do exist in the world — there’s a bit of Toad in all of us — and writers create stories around these characters rather than about them, per se. Frog turns Toad’s slump into a story because it is Frog who makes a plan: To write a letter to Toad. (Some kind of plan is necessary before a story works.)

Unfortunately, the snail who promises to help deliver Frog’s letter to Toad is very slow. This is where the young reader will be in ‘audience superior’ position. Readers of all ages will know that when a snail says ‘right away’, that does not mean ‘right away’.

These days, ‘snail mail’ appears to be a pun. But when Lobel wrote these stories he can’t have foreseen the day when regular postal mail was known as ‘snail mail’ to distinguish it from email. He wrote this before email became part of popular communication.

The snail ruins the surprise of a letter because Frog gets to Toad’s house first. Also, by the time Frog notices Toad’s slump, Toad is too far gone and refuses to check his letterbox anyway. So Frog and readers are robbed of the joy of seeing Toad receive his letter.

But really, would it be that fun to watch Toad open Frog’s letter? Would it, really? Sometimes it’s best if storytellers skip the entirely predictable parts of a story. This is why we don’t see a wedding or a funeral in The Power of the Dog. These off-screen scenes played out predictably, despite being designated life-changing moments for the characters. Some of the most interesting stories work because they zoom in on the small things: the let-downs in life, the small moments which appear to be insignificant but which are in fact turning points.

Something massive does happen in this story. This is the story where Frog tells Toad he loves him. Like a man who proposes by putting a diamond ring in a sausage, which is then swallowed whole, the dramatic plot (the romantic gesture of a letter) didn’t go to plan, but that doesn’t change the aesthetic reality between our two main characters.

Notice, too, that Frog is wearing the coat covered in buttons which Toad made for him the story before last.

Separately, I would suggest that Toad never gets any mail because there’s no postal service in the world of Frog and Toad. Someone has very optimistically put up a mail box hoping one will start up, but every other animal in their world is an actual animal, so.

FROG AND TOAD TOGETHER

Frog and Toad Together was a Newbery Honor Book.

A LIST

Toad likes routine. He likes to know what’s about to happen. This is probably a response to his generalised anxiety, which sometimes slips into depression.

Only a special kind of friend has the patience for an anxious type such as Toad, because Toad can sometimes barrel forth and impose his own plan upon Frog. This is what happens in this particular story. Toad does not so much invite Frog on a walk as insist he goes along. But Frog is the sort of creature who doesn’t mind last-minute plans. In fact, he thrives on novelty. This means he is up for a walk at no notice.

Toad’s list blows away on a gust of wind. Frog tries to catch it but can’t. But Frog sits with Toad in his anxiety until night-time. This is just the sort of friend Toad needs.

The end gag is a subtle word play on Toad being a ‘stick in the mud’. He literally takes a stick and writes in the swamp mud before allowing himself to fall sleep.

THE GARDEN

In the previous story, Lobel establishes Toad as a stick-in-the-mud who has a tendency to micromanage.

In this one, ridiculously, humorously, Toad thinks he can micromanage seeds as they grow into flowers. He must learn to relinquish control, as he cannot determine the rainfall, the soil temperature and so on.

Unable to step back entirely from his garden (inspired by Frog’s beautiful garden) he busies himself by ostensibly looking after the seeds but actually by looking after himself. He reads a story so the ‘seeds’ will not be afraid. He lights candles so the ‘seeds’ won’t be afraid of the dark.

Sometimes, when we think we’re doing something for someone else, we are actually doing it for ourselves.

There is a difference between caregiving and caretaking. The difference is that caretaking comes from fear: We want someone we love to feel better so that we can feel better ourselves. Genuine caring, or caregiving, comes from the loving part of ourselves.

It is only when Toad falls asleep that the seeds come out of the ground, flourishing on their own without his micromanagement.

The gag is that Toad never learns any of this. At the start of the story Frog told him that having a nice garden is ‘hard work’. Toad has misinterpreted the nature of the hard work entirely. Frog would’ve meant weeding, replanting, digging holes, that sort of work. Toad’s work has mostly been worrying, which had no bearing on the seedlings at all. He has no self-revelation regarding his own tendency to expend effort which has no bearing on results.

When comedic characters think they have an epiphany but it’s the wrong one, this is sometimes called an anti-epiphany. TV Tropes calls it an Ignored Epiphany, though for me this term doesn’t work because something has to be seen before it is ignored, and Toad doesn’t see anything at all. In psychology it is called self-deception, which can metastasise into denialism.

Here’s what Toad could have learned, were he in therapy instead in a darkly humorous early reader:

We can choose between responding to something out of fear or out of love. Choosing how to respond is the hardest part. We must first pay close attention to our own body and examine our own thoughts. We must accept our negative thoughts and name them for what they are, even if this is uncomfortable and challenges how we see ourselves. The next choice we make: we either speak and act out of fear, or out of love. Choice is at the heart of everything we experience. When we remain unaware of our own emotions we will continue to respond out of fear.

By the way, do you think Toad can really play the violin? I think those seeds were waiting for the screeching to stop.

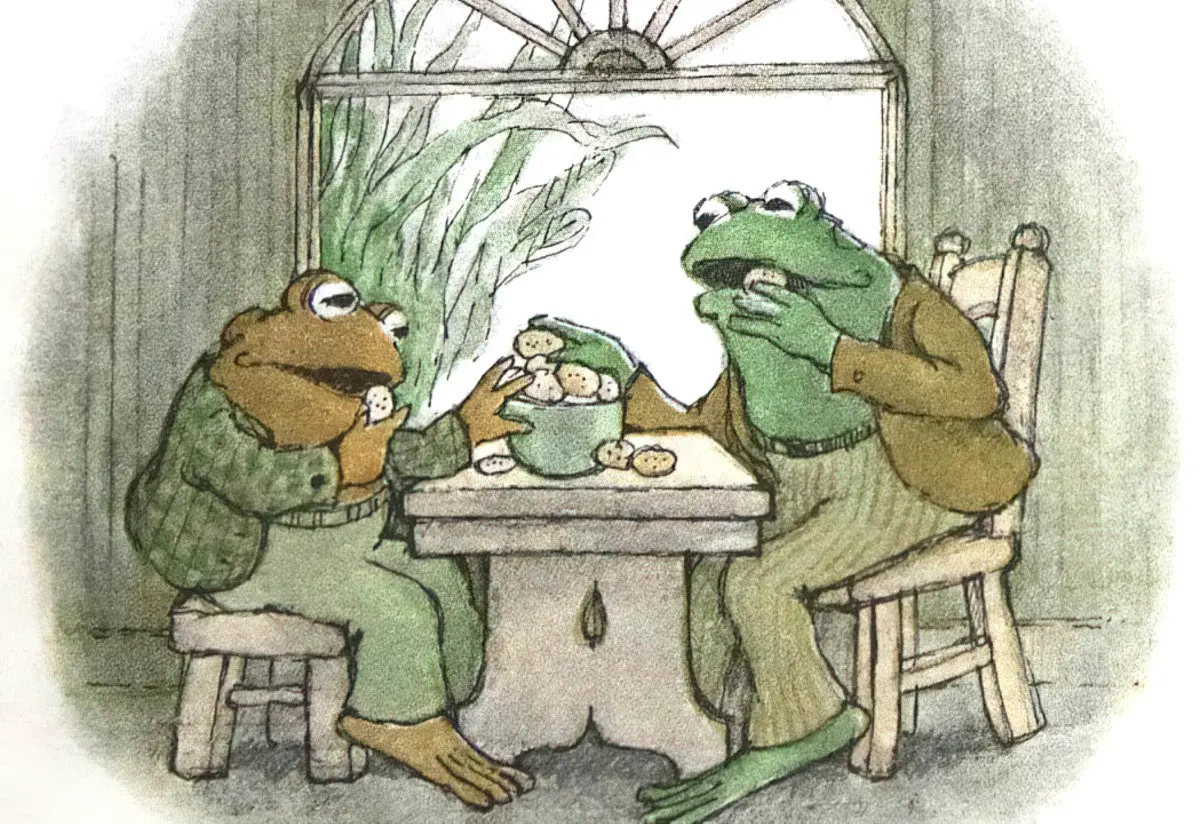

COOKIES

What is love if not, “I saw this and thought of you?” Or, in this case, “I baked these delicious cookies and I ran straight to your house so you could try them, too.” These cookies are an expression of Toad’s love for Frog.

The psychological battle in this story: Toad and Frog agree they should stop eating cookies otherwise they’ll both get sick. But the cookies are too delicious. They come up with various ideas for how to hide the cookies from themselves, but hiding something from yourself never, ever works. You always know it is there.

Eventually, they get rid of the thing they cannot hide by giving it away entirely. (They give the cookies to the asshole birds. More on them below.)

But Toad cannot bear being without this delicious part of himself, so scurries straight home to bake a cake.

On the page, this is a story about willpower, but it is really about accepting the part of ourselves which we cannot change.

The cookies could be anything, for example conversion therapy. More broadly, the desire to rid yourself of cookies might come from a dominant culture which does not accept what (or who) you love. Notice that Toad and Frog both love these cookies equally, and they share the experience together.

DRAGONS AND GIANTS

Once again, Lobel takes a common picture book plot and adds friendship aesthetics to it.

The plot? Two characters leave the house, go on a journey, encounter various scary creatures and situations, then return home. This is known in children’s literature circles as the home-away-home plot but is itself a take on the Odyssean mythic journey. (In the adult version, the hero doesn’t necessarily return home, but always ends up a different person.) Bears in the Night is your archetypal example of this type of story written for a single (not dual) audience of children. Young readers delight from the fright.

In fairy tales, heroes don’t need much of a reason to leave home. Third brothers leave home simply ‘to seek their fortune’. Modern storytellers add more detail, and there is usually some kind of quest or mission: Something to be conquered, something lost which must be found… etc.

Why do Toad and Frog leave the house? They’ve been reading a book of such fairy tales and may have come to the conclusion that leaving one’s house is mandatory. They would like to test their own bravery. Toad may fear he is on the precipice of full-blown agoraphobia.

In the previous story, Lobel wrote about the queer experience of denying joy in a culture which does not permit queer euphoria. Following on from that, I find it impossible not to read this story as an allegory for venturing out into a queerphobic world with the omnipresent, lurking threat of gay hate crime.

Frog and Toad ultimately seek refuge in each other.

Arnold Lobel didn’t live long enough to see a culture in which it became safe to talk about non cishet relationships, but unlike Kenneth Grahame, he left behind a daughter who has been able to talk about the queerness of Frog and Toad a little. Lobel’s daughter has said that Frog and Toad are an early fictional example of two same sex animals who love each other. This was her father starting to come to terms with his orientation.

Go back into stories from antiquity, and we find many stories about men who love each other.

Take Achilles and Patrolcus, close comrades in the fight against the Trojans. In the 5th and 4th centuries BC, their relationship was portrayed as same-sex love (cf. the works of Aeschylus, Plato, Pindar and Aeschines). In that era, in that part of the world, homosexual love was no biggie; morality centred around how much control one had of one’s urges, and had little to do with gendered orientation. Foucault wrote all about that.

By the way, I mostly code Frog and Toad as gay because we know that Arnold Lobel was gay. Sticking to what’s on the page, however, I code Frog and Toad as homoromantic aces. It’s overly simplistic to collapse romanticism and sexual orientation into a single aspect of a person, but romantic attraction and sexual attraction are different.

THE DREAM

Toad has a dream which turns into a nightmare. If we go Jungian with the dream, Toad’s showing-off on-stage suggests a desire to be seen, truly seen, by Frog. Not only that, he wants to impress.

But he worries that if he hoards all of the grandness for himself, this will diminish his best friend. In the dream, Frog’s shrinking corresponds to Toad’s own impressiveness. What he really wants is to be seen, but not as better than who he really is. After all, he can’t really play the piano without making a single mistake. His deepest desire is to be seen for his Toady flaws, and loved by Frog anyway.

Frog arrives and wakes Toad from his nightmare. They spend ‘a fine, long day together’ and the outro image shows Toad giving Frog a piggyback, or perhaps they are playing leap frog.

Leap frog is a game in which players take turns leaping over one another; no one is ‘king’ over the others. It is a truly reciprocal pastime with no winner and no loser. Everyone is a frog.

FROG AND TOAD ALL YEAR

DOWN THE HILL

This story begins like the first in the Frog and Toad series: Frog raps upon Toad’s door and tries to coax him out of bed to go outside and play in the snow.

Toads in cold regions do hibernate in the winter. Many frogs do, too, but some kinds of frog (tree frogs) aren’t very good at it. They sometimes try to burrow into a crevice and end up freezing to death. The frogs who hang out at the bottom of ponds have better luck.

Well, that’s depressing. Back to Frog and Toad: if Lobel was thinking of real frogs and toads when he wrote this series, I’m guessing he was thinking of a tree frog for Frog, because Frog isn’t good at hibernating. He’s out and about, wanting to have fun in the snow.

Turns out he’s not very good at that, either, because despite his enthusiasm for sleds, he flies right off the back of it.

Toad starts to have fun, thinking how wonderful it is and how safe to be on a sled guided by Frog, who is sitting right behind him, keeping him safe. A bird tells him Frog is not, in fact, sitting behind him. This is the bit where Toad freaks out.

Without Frog, Toad almost plunges to his death. (Thanks, bird.) Frog has been watching from the top of the hill and comes to pull Toad out of the snow.

The reader learns a ‘mind over matter’ lesson, but Toad doesn’t. He goes back home to bed, as grumpy as he was at the start of the story.

Men were permitted to be more overtly joyous in earlier times. This jockey advertisement looks overly performative, sure, but the guy also looks joyous.

Contemporary audiences might view this as homoerotic. Not something that crossed the minds of most WW2 audiences.

THE CORNER

In the best story-within-a-story structures, the wrapper story is thematically related to the story one diegetic level down.

In the wrapper story, Frog and Toad were caught in the rain. They seek refuge at Frog’s house. Toad isn’t happy about being soaked (despite being an amphibian, which adds a layer of humour). Frog tells him to dry himself by the stove. He provides tea and cake.

Recognising that Toad is cranky, Frog tells him a parable. (Or is it a fable, since the characters are animals? What if the animals telling the story are coded as human… The distinction between parable and fable is far from binary.)

In Frog’s story, his wise father tells him spring is just around the corner. Spring is a metaphor for good times after bad. Frog keeps looking round corners but finds disappointing, ordinary things, not spring. Then it rains. Pathetic fallacy (rain as sadness), linking the parable back to the wrapper story.

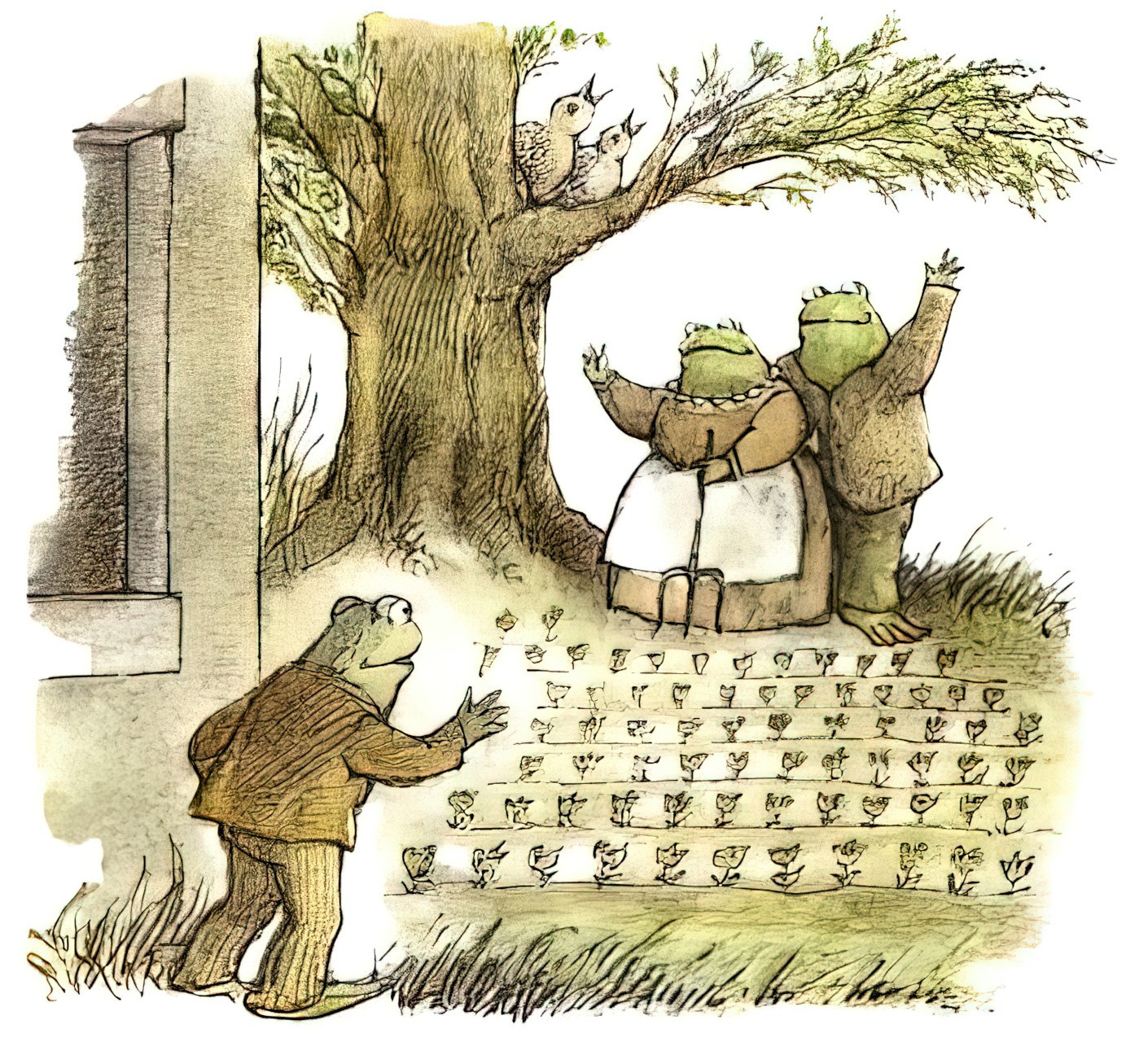

Eventually he tries peeking around the corner of his own house and sees the sun coming out, and his cherished parents in their vegetable garden.

The parable teaches Toad (and the reader) that no matter how bad things seem right now, hold onto the idea that things will eventually get better. Because they will.

The story ends with Toad and Frog checking round the corner of Frog’s house ‘to make sure that spring has come again’.

From the window casing it is clear that Frog has inherited his parents’ house. He never left home; his parents must have died.

This is not a part of the story, but when Frog ‘sees’ his parents in the garden, waving from the other side of it, I feel like they’re ghostly apparitions.

ICE CREAM

Julia Donaldson wrote the foreword to The Complete Collection. I see similarities in their work. Lobel’s “Ice Cream” is reminiscent of Donaldson’s “The Gruffalo“.

Frog and Toad sit by a pond, as frogs and toads sometimes do. They fancy some nice, cold ice-cream, as humans sometimes do. Toad goes to the shop and buys two big ice-creams but on the way back to the pond they melt onto his face and he looks like Elephant Man.

A mouse alerts Frog to a terrible creature coming their way. Then other animals bring warning. Frog hides behind a rock.

But when Frog sees the monster with horns (actually cones) he knows from Toad’s voice that the ‘monster’ is his friend Toad. This is where Lobel departs from typical picture book plots.

The expected thing would be for Frog to get a big fright, not knowing it is his best friend. Young audiences enjoy watching a character get a fright. The unmasking phase of a story is often the most satisfying for the audience — a result of all the hero’s hard work (in a detective story) or a deep breath (in a thriller). In a comedy, the audience is often in superior position. Young readers know it is Toad; Frog does not.

Lobel doesn’t give readers that small thrill. Why not?

Because a true friend knows us, sees us, even when we are are looking our worst. A transgression comedy, with its compulsory unmasking at the end, would go against the main rule of the Frog and Toad story world: These two characters know each other deeply, and accept each other as they are.

THE SURPRISE

Lobel has already shown us how Frog and Toad’s relationship is caring and fully reciprocal. It is reciprocal despite utilising a commonly seen comedy duo: The grumpy, depressive one and the enthusiastic one. (Mitch and Cam of Modern Family are absolutely this.)

Lobel’s “The Surprise” is the ultimate example of reciprocal caring because Frog and Toad both do exactly the same favour for each other (raking leaves) without the other knowing about it.

The wind ruins their plans by messing up all the leaves before either character can notice the favour the other has done. Both Frog and Toad derive much enjoyment from doing something for a friend with no expectation of reward. Both go to bed thinking of how pleased the other must be to find their yard raked.

There is no unmasking phase in this story, either. And this is the main difference between a Frog and Toad story and more typical stories. Neither character ever finds out what happened.

The aesthetic, fable layer? It is better to give than to receive. This message can also be found in the Bible. It speaks a wider truth about humanity and relationships:

I have shewed you all things, how that so labouring ye ought to support the weak, and to remember the words of the Lord Jesus, how he said, It is more blessed to give than to receive.

Acts 20:35 (King James Version)

Other stories about doing something for someone else include:

- The Giving Tree (problematic to many readers because of the extreme and gendered self-sacrifice within a wider culture of misogyny)

- The Very Cranky Bear (has the exact same issues as The Giving Tree but is newer, and Australian)

- Sidewalk Flowers (avoids this issue entirely; the femme-coded main character keeps a flower for herself)

A large proportion of picture books about sharing and kindness involve a character arc in which toddler-like characters learn that sharing is a kindness.

CHRISTMAS EVE

Toad’s clock is broken. We almost forget this fact, which only comes back at the end, as the story comes full circle. (Like an analogue clock.) Frog and Toad are masculo-coded but the stories are femme-coded, insofar as plot structures are binary gender. Looking at stories written ‘for girls’ and stories written ‘for boys’, the girl stories are centered around the home, intimately to the seasons (and the moon — menstrual cycles, get it?). Boy characters in ‘stories for boys’ leave the house and go on a mythic journey, which makes them mythic.

That’s what I mean about girl stories. Academics have studied this stuff. (See Maria Nikolajeva.) Frog and Toad stories are girl stories even though they star boys. Gender is bullshit, yadda yadda, but gender rules are very influential, yadda yadda.

Have you forgotten about Toad’s broken clock yet? We forget about the clock because Toad is terribly worried about Frog, who he is expecting for a Christmas celebration. His worries spiral out of control. He has very specific fears about which terrible calamities may have befallen his best friend. To save his friend, Toad retrieves rope from the basement, a frying pan from the kitchen, and a lantern from the attic.

Like the expanse of his worried imagination, Toad goes up and down all over his house. He is frantic with activity. See? This is why Toad’s house needs a symbolic attic and a symbolic basement.

By the time Toad opens his front door to embark upon his rescue mission, Frog is there, about to knock. Frog was busy wrapping Toad’s Christmas present, which is a new clock.

It is now that we remember Toad’s clock is broken, and we realise Frog is not late at all. Without a clock to guide him, Toad has lost all track of time. Like his lists, he needs a clock to keep his imagination in check. (I would suggest Toad is a highly phantasic sort of creature.)

Frog understands all this about Toad and has known exactly what to get him for Christmas.

We never find out what Toad has got Frog for Christmas, but if you turn back to the first page of this story you’ll see a present under the tree. We can safely deduce this gift is for Frog, since Toad doesn’t have any other friends.

What do you think is in it? I would really like to know, but Lobel knows when to withhold information and let the reader’s imagination fill in some tantalising holes. Literal Mystery Boxing. Before Mystery Boxing had a name.

I think Toad gave Frog some paints and paint brushes. (Can you see why I thought that?)

DAYS WITH FROG AND TOAD

TOMORROW

This story teaches kids to clean up their room. I have encountered a few picture books with this lesson, none of them fun. But Toad is highly relatable when he thinks he’d rather stay in bed and ‘take life easy’ than clean up.

The ‘parental’ figure of this story is Frog, who turns up out of nowhere and points out all the things that need doing. But that’s where his parental coaxing stops, because Toad realises on his own that if he gets started today, and approaches tasks one small chunk at a time, he can relax properly afterwards without the guilt and the dread. He goes back to bed feeling better about life in general.

This form of coaxing is a more modern way of parenting than was popular in the 1970s, in which parents regularly said, “Good boy”, “Good girl”, without realising that they were creating external motivation in children but not framing tasks as an intrinsically motivated form of care, for self and others.

THE KITE

Three asshole robins appear in this one. (We’ve already seen an unhelpfully straight-talking Crow: “But Toad, you are alone on the sledge.”) Birds are the enemy in this series.

Frog and Toad try unsuccessfully to fly a kite. The robins, who can fly using their wings, which they grew themselves, laugh and laugh and tell them their kite will never fly.

True to form, Frog is not so easily discouraged. He tries something different rather than give up. The robins laugh and jeer.

The robins are a stand-in for our inner voice which tells us we can’t do something if it doesn’t work the first time.

I’m inclined to think the other animals in this animal utopia can’t talk at all — whatever they ‘say’ is really the inner voice of Frog and Toad, the only animals who can communicate with each other.

Making use of the rule of three, the kite does fly on third attempt due to a combination of running, waving, jumping and shouting. The reader will understand that the shouting has nothing to do with the physics; the shouting is an expression of perseverance and enthusiasm in the face of difficulty.

The kite ends up flying higher than those robins ever could. Frog and Toad watch it meditatively. The kite is a symbol of their high spirits.

SHIVERS

What is the raison d’être of the horror genre? Audiences watch horror for various reasons, but one pleasurable sensation is ‘horripilation’: That physical sensation of high alert in the face of possible threat. This must be what dogs feel when they raise their hackles at birds. (Or is that just my dog?)

This story begins with a take on, “It was a dark and stormy night.” (“The night was cold and dark.”) Like “Once upon a time”, this opening is from the oral culture of storytelling and alerts listeners to what kind of story they can expect.

Very young children love picture books which induce this feeling. My own kid’s favourite horror story was It’s A Bear! by Jez Alborough. Hallowe’en books such as Creepy Carrots by Aaron Reynolds and Peter Brown are also successful in creating pleasurable thrills. The rule: The kid has to return safely home.

But Frog and Toad are already at home. Frog makes a ‘fresh pot of tea’, sits down and begins to tell a story. He tells Toad a story with all the good tropes: Getting lost in nature, a cannibalistic legendary creature, dark woods, two huge eyes.

Toad interrupts to ask if this is a true story but Frog replies mysteriously, “Maybe yes and maybe no.” Toad asks another few times as Frog recounts how he fools the monster frog and ties him up with his own skipping rope. Fortunately, ogres in fairytales are stupid and easily fooled.

Frog never reveals whether the story is true or not. He has managed to scare himself as well as Toad. They sit in front of the fire with their teacups shaking. Lobel makes sure to tell us that they are enjoying this feeling very much.

THE HAT

We have already seen how Lobel plays with size in these stories for children. Children’s books — like fairy tales — are full of shrinking and growing, and massively oversized objects, infestations of creatures (mainly cats and mice though they could be Minions) and tiny little people (sometimes in mice bodies) living among the regular folk. When storytellers play with size, they create resonant imagery.

We’ve already seen an oversized hat in Lobel’s “The Dream”, in which Frog shrinks, in contrast to the large feathered troubadour hat which Toad wears to show off in.

This story is like a kind version of Roald Dahl’s The Twits. The Twits are a married couple who are absolutely horrible to each other, constantly playing mean pranks. The story is so mean that our standard two (Year 3) teacher refused to read it to us. In one prank, Mr Twit keeps adding increments to Mrs Twit’s chair legs, to convince her she’s got ‘the shrunkles’.

Lobel’s “The Hat” utilises a similar sort of plot: One character secretly does something for another while convincing them that their body is changing. But the intention is completely different, because Frog has accidentally gifted Toad a hat which is too big for him. Toad refuses to stop wearing it because Frog gave it to him for his birthday and it is therefore special. But he keeps hurting himself because it falls down over his eyes and he can’t see where he’s going.

Frog tells him to go to bed and think big thoughts. That way his head will grow bigger.

Toad goes to bed and thinks about the largest things he can, enjoying the sublime in high mountains covered in snow and so on. Note how the mountain shrouded in cloud looks like it is wearing a hat. Toad is prone to self-aggrandising dreams, which is ironic considering he doesn’t exhibit much self-confidence while awake.

Meanwhile, Frog creeps into Toad’s house. He retrieves the hat from Toad’s coat stand (only the hat is on it), takes it back to his own house and shrinks it by soaking it in water. He carefully puts it back where it was.

Now the hat fits perfectly. Frog and Toad re-do Toad’s special birthday by going on another walk. This time Toad doesn’t bump into anything and they have a much better time.

ALONE

Deep friendship is secure friendship. Securely attached friends understand that just because you want some time alone doesn’t mean you’re breaking off the entire thing. Friendships are possibly even more difficult to navigate than romantic relationships because we have scripts for ending them. Sometimes people break the rules for ending romantic relationships, in which case we call it ‘ghosting’. But how do we end friendships? We don’t call it ghosting, but ghosting is how it’s typically done: One or both parties back slowly away. Neither party acknowledges that this is what’s happening.

Tacking a note to your door saying you want some time alone isn’t exactly an emotionally literate thing to do. I mean, some indication you’re not mad is necessary here. And that aggressive full-stop. These guys are clearly of the Silent Generation, correctly punctuating sentences ‘correctly’. I don’t imagine Frog would think much of text speak and emoticons.

Honestly, this note feels a little out of character for Frog by this stage. I might expect a note like this from Toad, but isn’t Frog always up for everything?

This is the exact point, of course. All the way through this series, Lobel has been careful to avoid the easy binary character duo of a depressive one and a happy-go-lucky one. It is high time Frog was allowed a little down time. I was starting to think Frog is doing a little too much of the heavy lifting in this relationship anyhow. He’s always the one pumping Toad up, getting him out of bed, coaxing him into tidying his house, coming up with the stories. He does so much work in this friendship it makes sense that he needs time to recharge before once again tending to Toad’s gigantic needs.

These guys don’t really respect each other’s needs sometimes. We’ve earlier seen Frog literally pull Toad out of bed and dress him in outdoor gear. Sure, it was his own benefit and Frog knew Toad would eventually enjoy himself, but these stories aren’t what you’d turn to when teaching consent.

Rather than leave Frog alone, as clearly requested, Toad looks in the windows, looks in his garden… He eventually finds him on an island by himself.

Toad knows what it’s like to be down in the dumps, wishing for company without being able to ask for it. I mean, that’s Toad all over. So he assumes this is what’s happening to Frog.

Toad returns home and prepares a picnic to cheer Frog up. Fortunately, this allows Frog all the alone time he needs. By the time Toad returns with the cheer-up picnic, and finds a turtle to transport him to the island on its back, Frog is pleased to see him.

True to form, Toad has anxiety-spiralled into believing Frog doesn’t want to be his friend anymore. Symbolically, the picnic gets spoiled in the sea journey.

But Frog isn’t sulking or wallowing at all. He reveals that he only wanted to be alone to think of how wonderful it is to be a frog ‘and because I have you as a friend’.

Moral of the story: Alone time doesn’t mean wallowing.

I feel this is a message extroverts have been slow to pick up on, though a lot has been said about introversion since Susan Cain’s book. now the extroverts of the world are feeling misunderstood. When the Frog and Toad books were published, we were nowhere near that point.

CONFLICT AND KINDNESS IN FROG AND TOAD

What are the takeaway points about storytelling and kindness? Can lessons from the Frog and Toad stories carry over into other genres?

First up, adult audiences love kindness. There are many, many examples of unexpected kindness in popular stories. ‘Unexpected’ is key. Kindness feels cathartic after great misunderstanding or other kind of conflict. When storytellers take a mean character and show them being kind, this is a sure-fire way to create pathos in the audience.

In their own small ways, Frog and Toad are mean to each other. They are mean without trying to be mean. It’s not even ‘meanness’; Frog wants to play, Toad does not.

In some of the Frog and Toad stories, the two friends want exactly the same thing e.g. to enjoy a scary story. The opponent then comes from the story-within-a-story.

We are told stories don’t work unless opposition is human. It’s all very well to create a cyclone or a flood as opposition (as in a disaster story), but this isn’t enough to sustain interest. The cyclone/flood is simply too powerful. A story feels hopeless and unsatisfying. Stories do require human (or anthropomorphised) conflict. Frog and Toad are the human opponent for each other. They resemble archetypal romantic opponents, sometimes secure in their long friendship, at other times suddenly plagued with relationship-doubt: We cannot become too complacent even in our most secure relationships, Lobel teaches us. A bit of occasional insecurity can remind us how lucky we are to have someone. So it is for Frog and Toad.

Sometimes, Toad’s worst enemy is his own inner-voice. Lobel externalises Toad’s inner voice by giving them the form of talking birds. Birds work well because they can appear out of nowhere and, like an annoying inner-voice, hover above his head. They don’t go away until Toad himself conquers them.

Even in stories for an adult audience, the inner-voice is frequently given human form. Writers call this The Shadow In The Hero, but it comes from Jung. An opponent attacks a hero’s greatest collection of weaknesses.

Stories don’t need villainy — unless they are superhero stories or a related genre. We are such complex individuals that even in the most loving circumstance, we will butt heads with those we love the most.

FOR FURTHER INVESTIGATION

Frogs and Toads in Art and Illustration

A list of Frog and Toad tropes at TV Tropes

Film director Chloe Zhao makes stories which contain great kindness. Even within these stories of kindness, characters come head-to-head, because they each have their own weaknesses and want different things. See Nomadland and also The Rider.

There is a 1985 claymation adaptation of Frog and Toad Are Friends.

At McSweeney’s there’s an article called Frog and Toad Are Self-Quarantined Friends, which I’ve seen shared a number of times since the start of the 2019 pandemic.

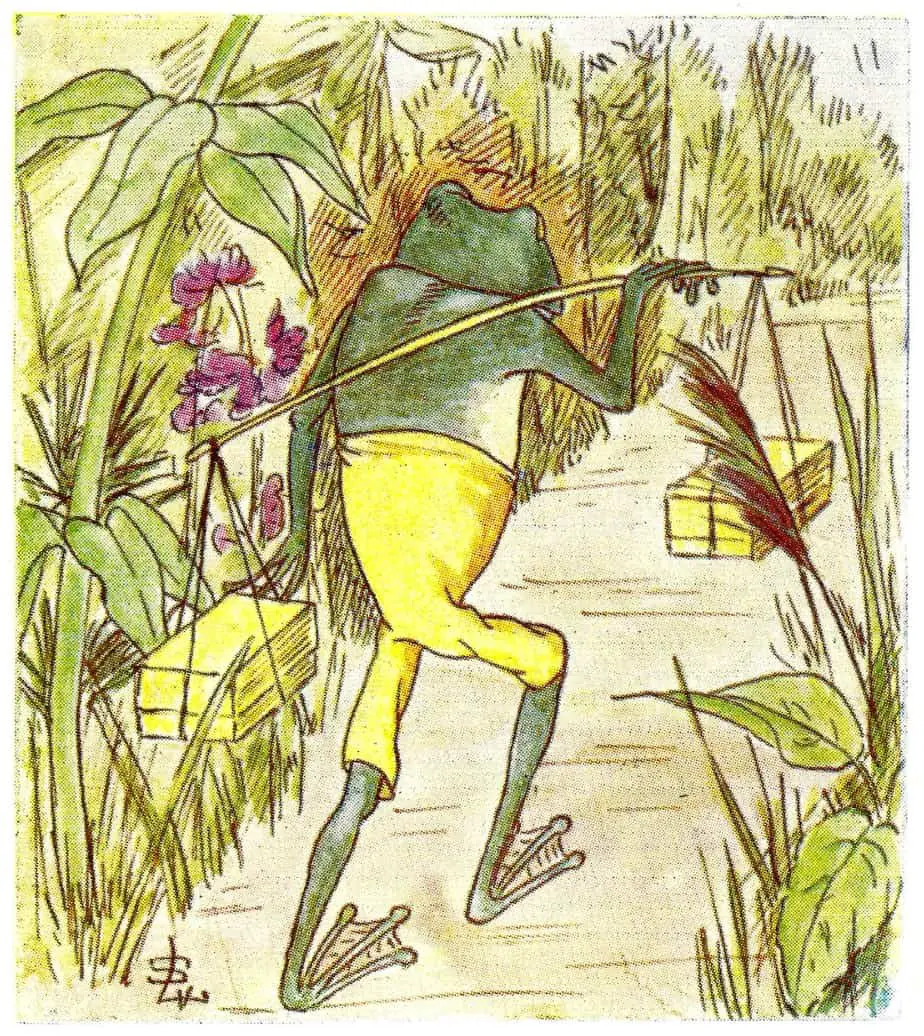

Unfortunately for me I can’t read Dutch otherwise I’d check out the story Het kikkerboekje, out of copyright and therefore available online. This frog looks charming to me, in the same way as Lobel’s amphibians look charming.

The following thread on the things abled people could learn from the disabled community might be a round-up of how Frog and Toad love each other:

Non-disabled people in my life don’t know how to love me like disabled people do. I’m so thankful for all my disabled friends who know how to provide care, rest, support and love. Disabled love is critically different from my other interactions with the world.

I really wish non-disabled people could learn to love in the same caring modalities. Love looks like remembering my food intolerances. Love looks like saying “that sucks” when I complain. Love looks like calling to check in and telling me stories.

Love looks like someone bustling around at home doing everyday things that wanted to call just to be with me across time and space. Love looks like not trying to fix everything and just allowing bad days to be bad. Love looks accepting my need to isolate as much as possible.

Love looks like spaces for shared grief. Love looks like celebrating our mere existence and survival in a world so set on eradicating us. Love is everywhere in disabled communities.

Originally tweeted by Nicole Lee Schroeder, PhD (@Nicole_Lee_Sch) on April 15, 2022.

Life lessons about solitude, from a frog and a toad from NPR