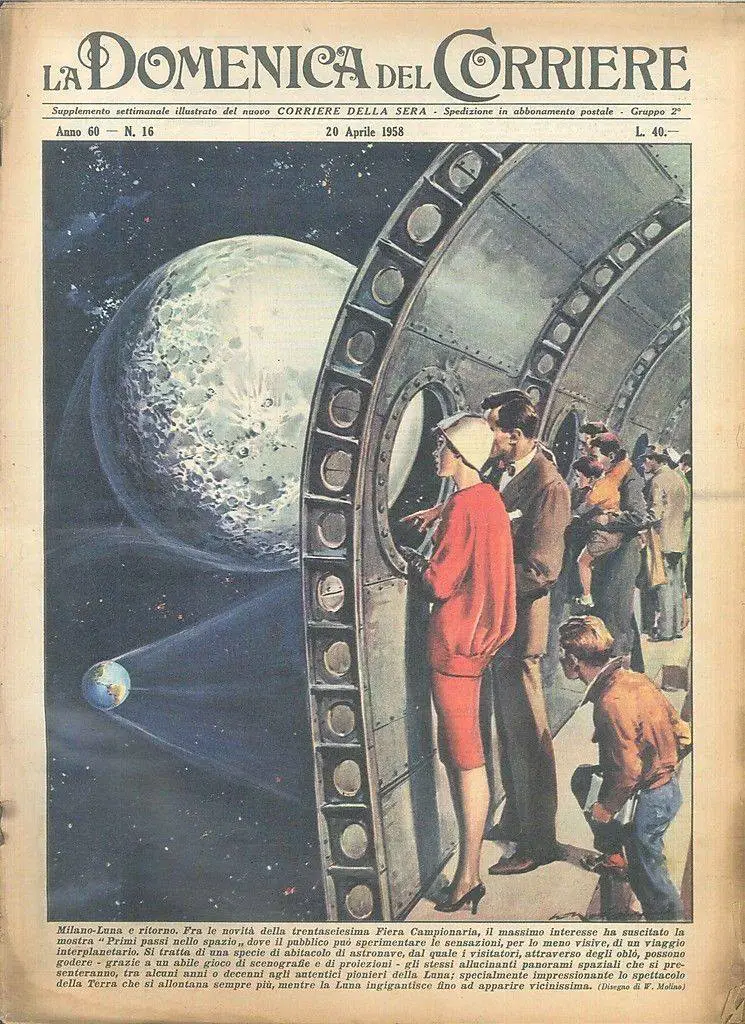

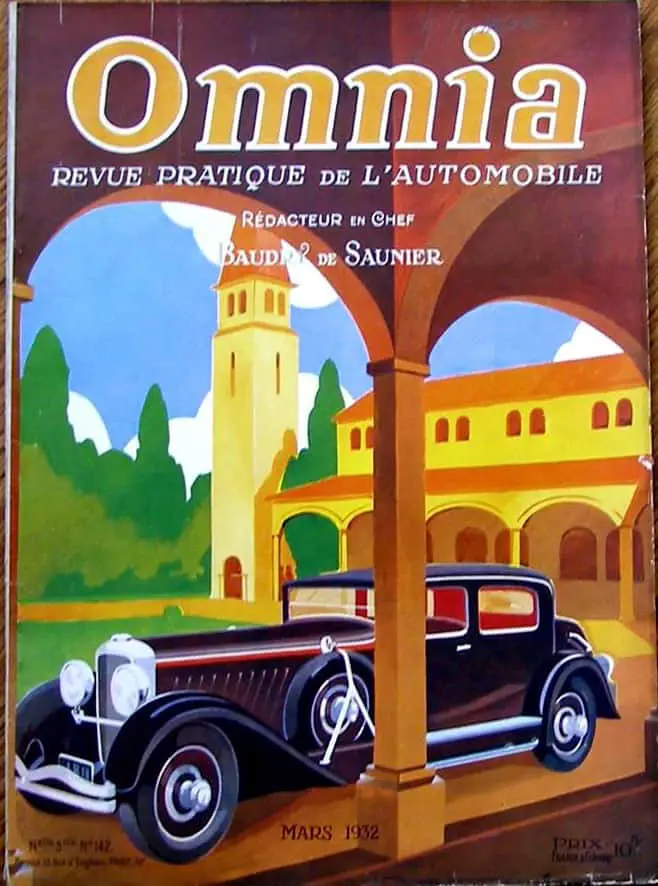

As a framing device, arches, archways and arcs are useful to illustrators. Below are various examples of archways in art and illustration.

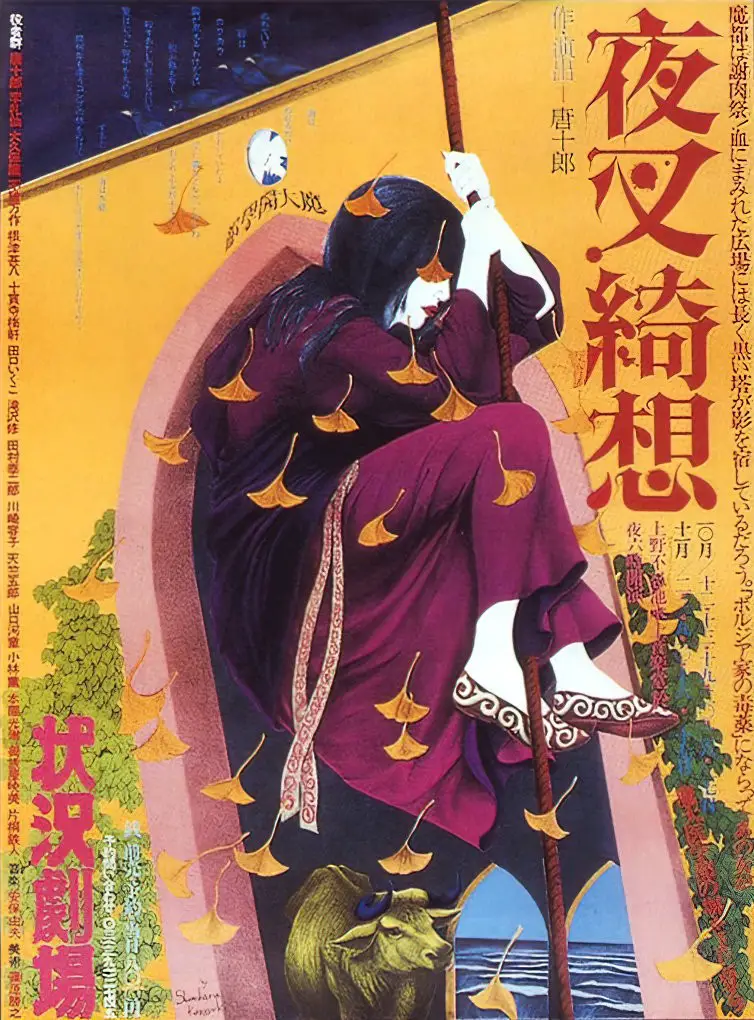

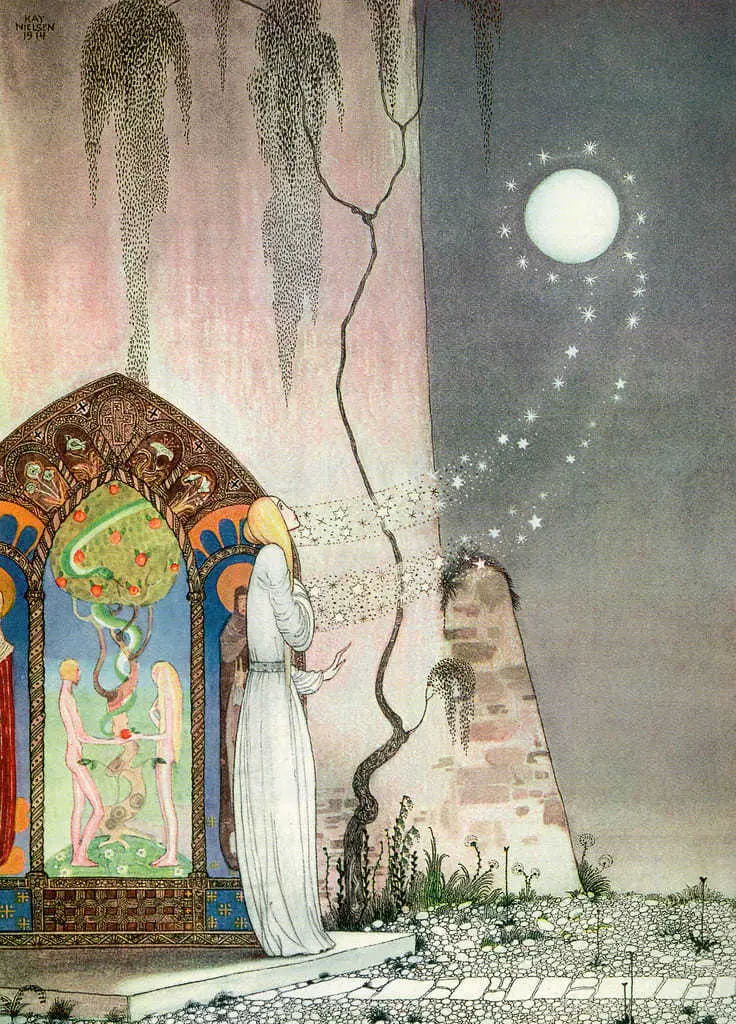

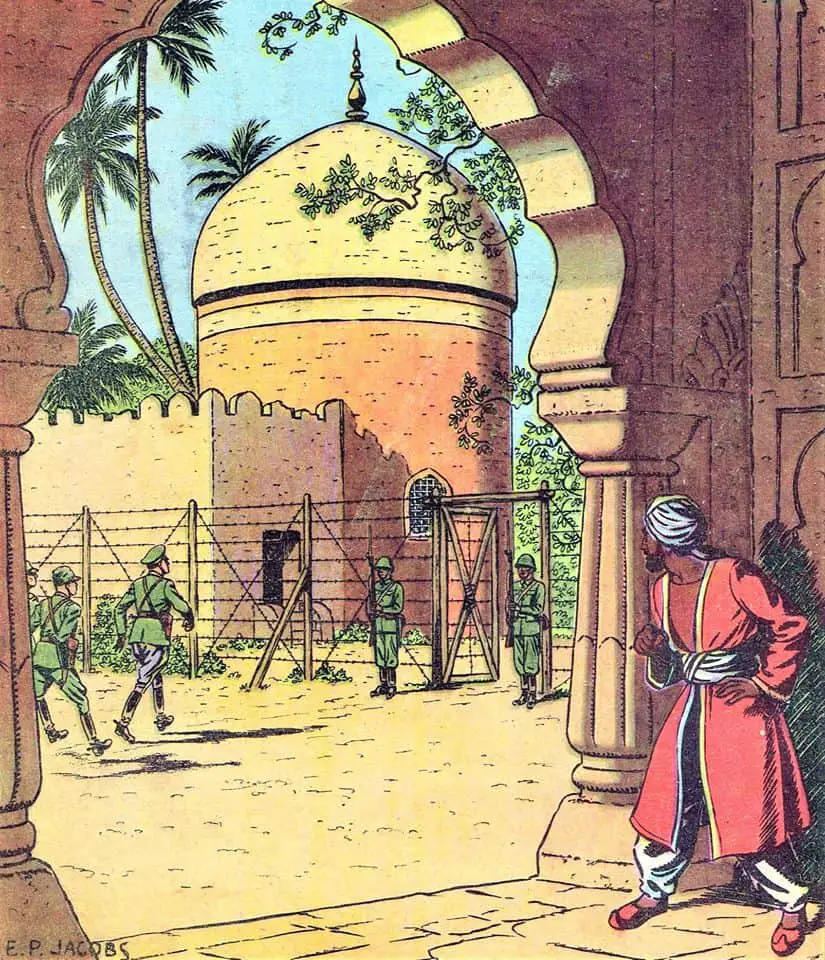

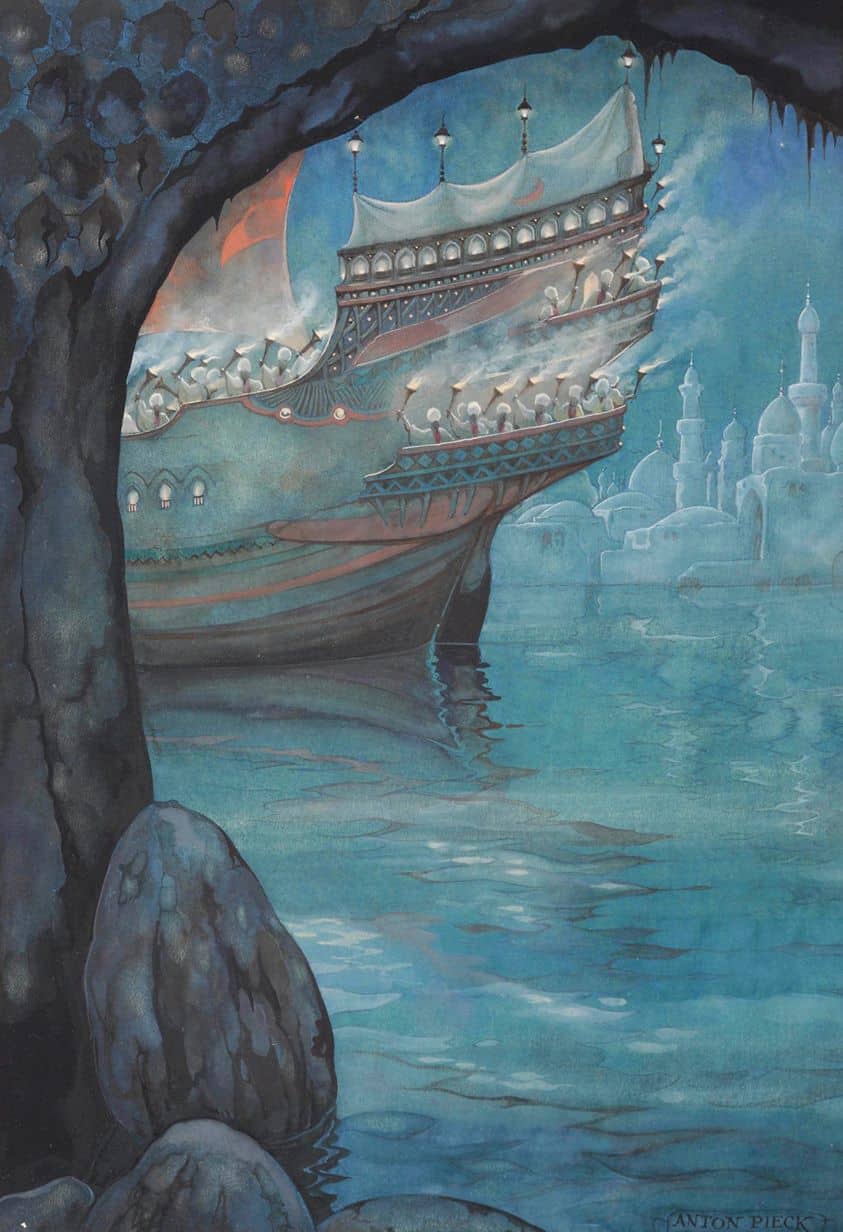

If you look up symbolism of the arch, you’ll be taken to the underworld of tarot readings and superstition. These days, the archway is considered a practical and aesthetically pleasing architectural structure, but in fiction and art still functions as what academics might call a boundary into liminal spaces. Fantasy enthusiasts might think of it as a kind of portal.

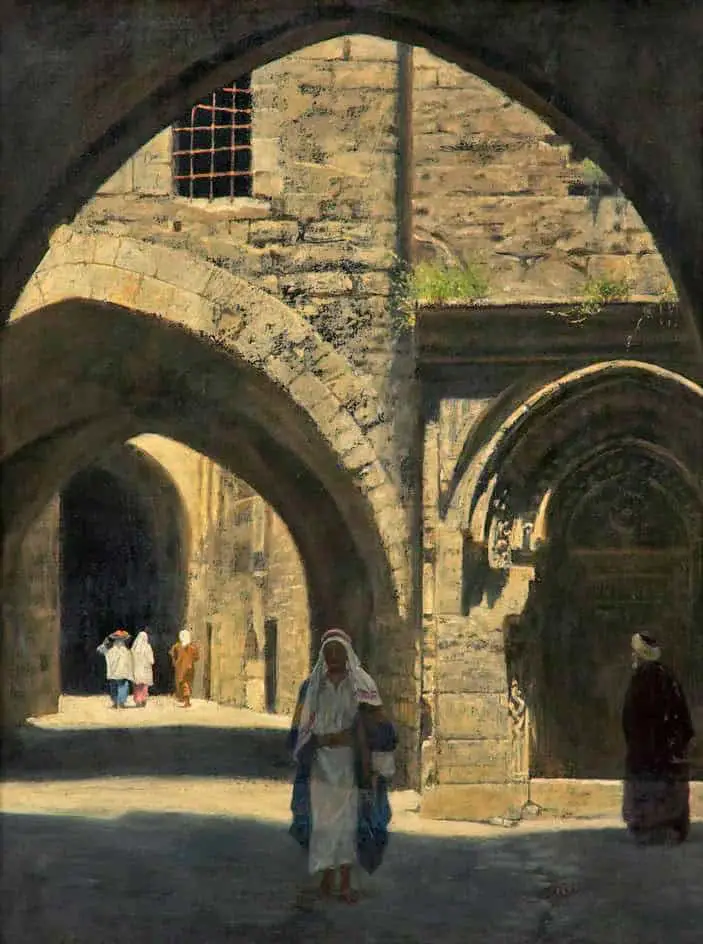

These ideas around archways (and similar structures) transcend time and culture.

What’s the inverse of an archway. You probably won’t think spontaneously of ‘meadow’, but Ruth B. Bottigheimer made a study of fairytale illustrations. Because there are so many collections of illustrated fairytales, she focused on fairytale collections in which each story featured a single image. Which part of a fairy tale do illustrators consider the most worthy of capture? Bottigheimer honed her study down further to the tale of “Goose Girl”. The paper is called “Illustration and Imagination”, and lists the three main conclusions:

- Overall design of illustrations remained constant over decades.

- Particular details within the illustrations gradually changed in ways that reflected changing cultural expectations.

- Illustrators’ choice of illustration moment in “The Goosegirl” reliably predicted how the same illustrator depicted heroines in other tales: archway illustrations were associated with a heroine’s humiliating degradation, while meadow scenes correlated with a heroine’s shining triumph.

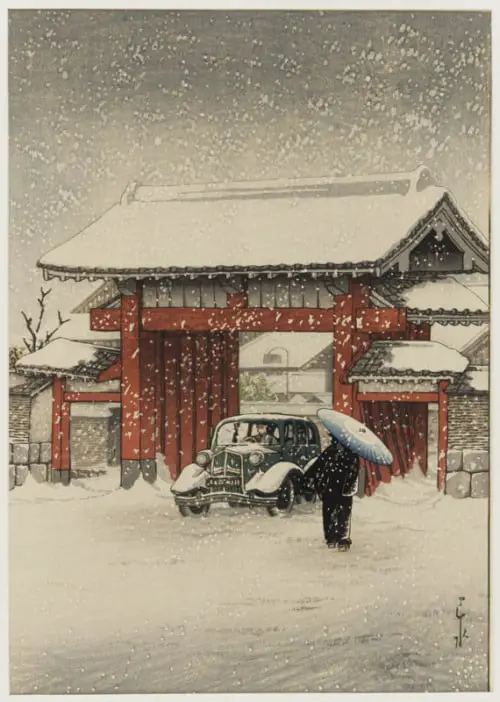

In some cities and towns, street architecture offers many beautiful views.

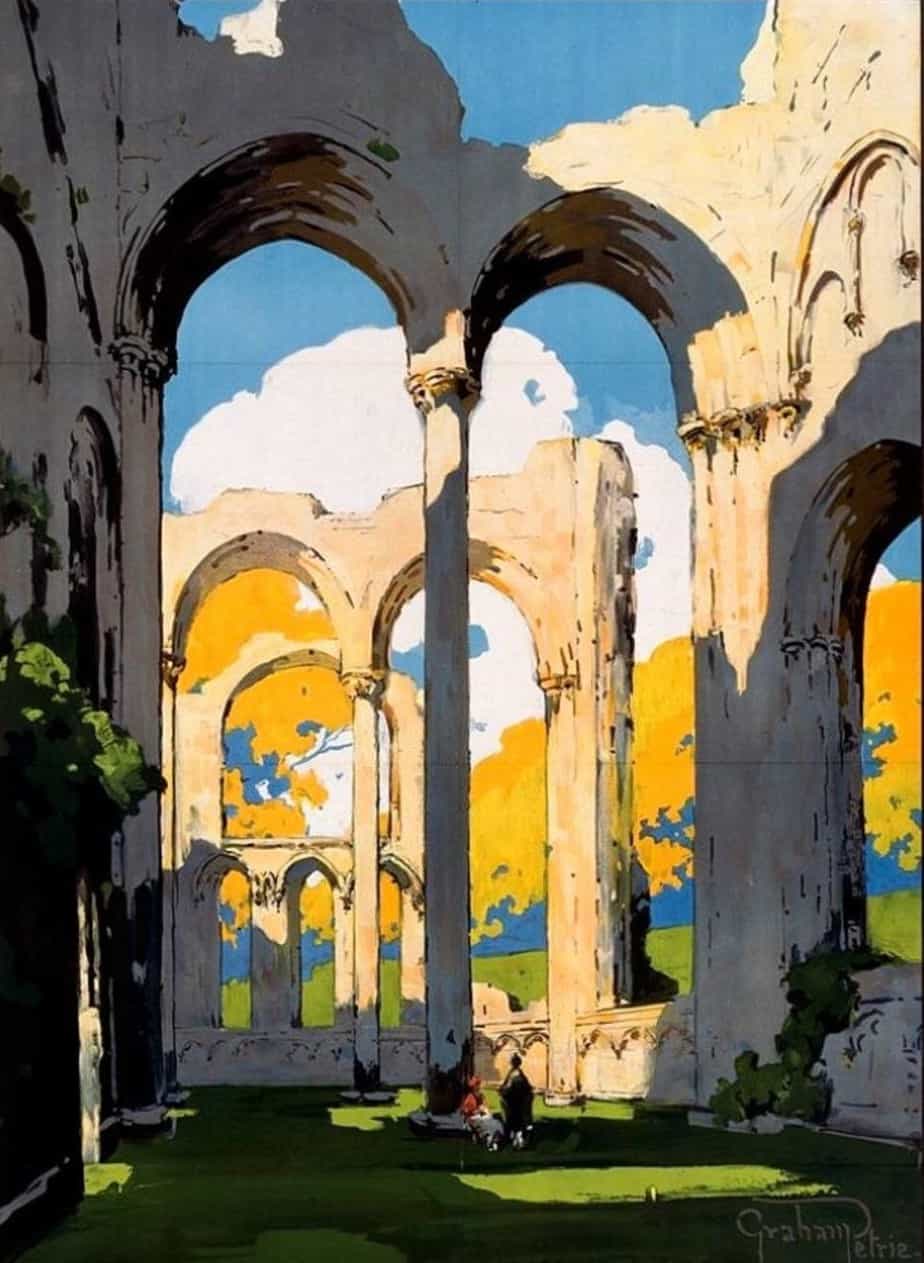

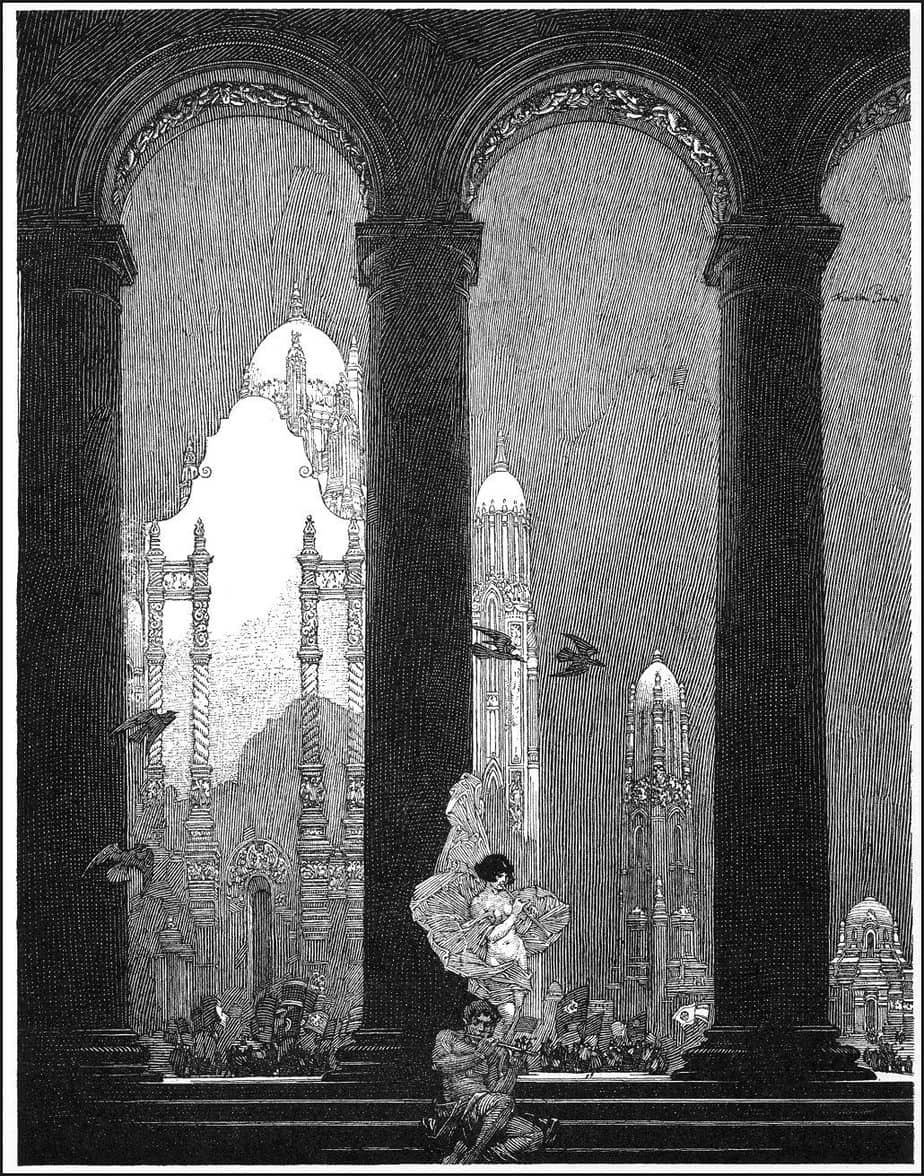

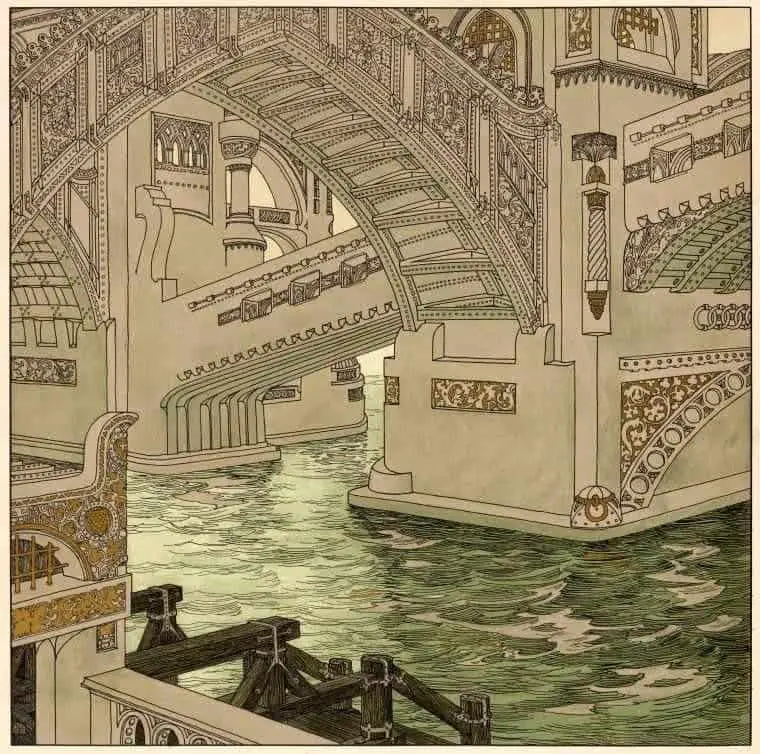

The examples below are two-point perspective, using the archway as a simple frame, or a diptych (almost a triptych) in the example by Franklin Booth.

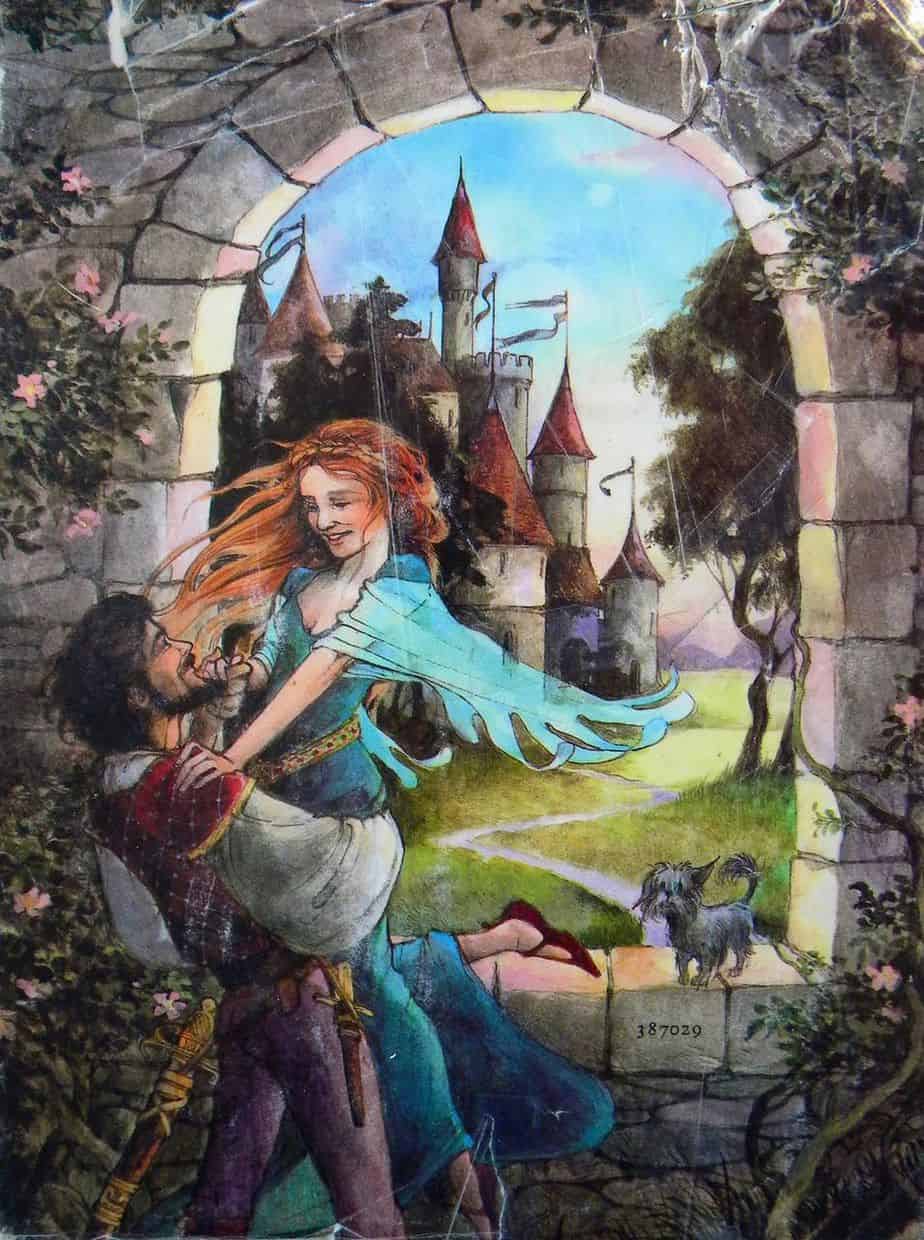

When illustrating The Sleeping Beauty, Trina Schart Hymen made much use of archways in framing. Aside from the compositional reasons, we can pinpoint the practical: a storybook (Medieval) tower features archways for windows. But the arches of Sleeping Beauty are equally symbolic, functioning as a ‘keyhole’ view of the world. This is another young woman cossetted in an attempt to keep her safe. See also Rapunzel and many other fairytale princesses.

The arch is a strong structure — a ‘pure compression form’ in engineering terms, and often the last thing standing after a castle ruin.

See: How Bridges Work from How Stuff Works.

The archway isn’t always a simple arc. Here is a decorative example, with a mise en abyme arch-within-an-arch effect. The rich people in the gallery are as removed from the plebs below as the plebs are removed from the fiction playing out on that stage.

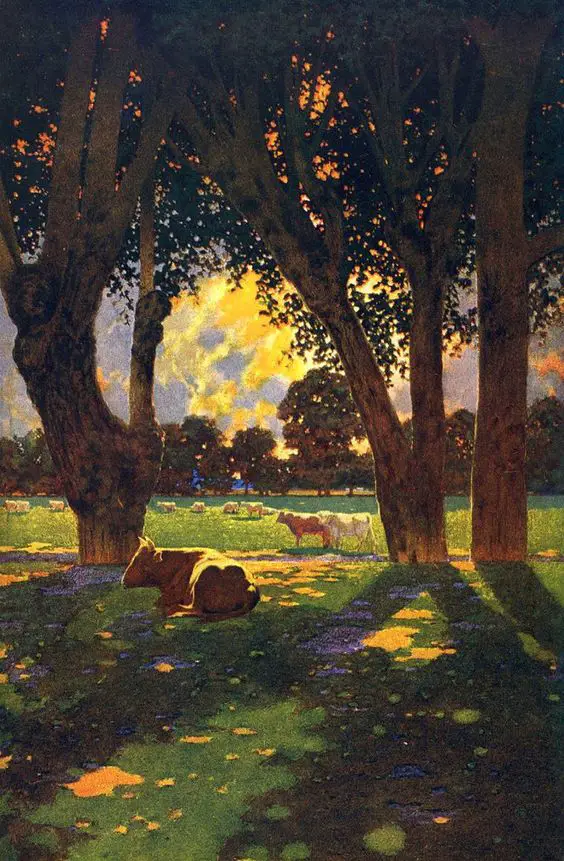

Trees can form a natural, beautiful arch, turning a natural scene into a type of dwelling, almost a cathedral in this case. The forest is nature’s cathedral.

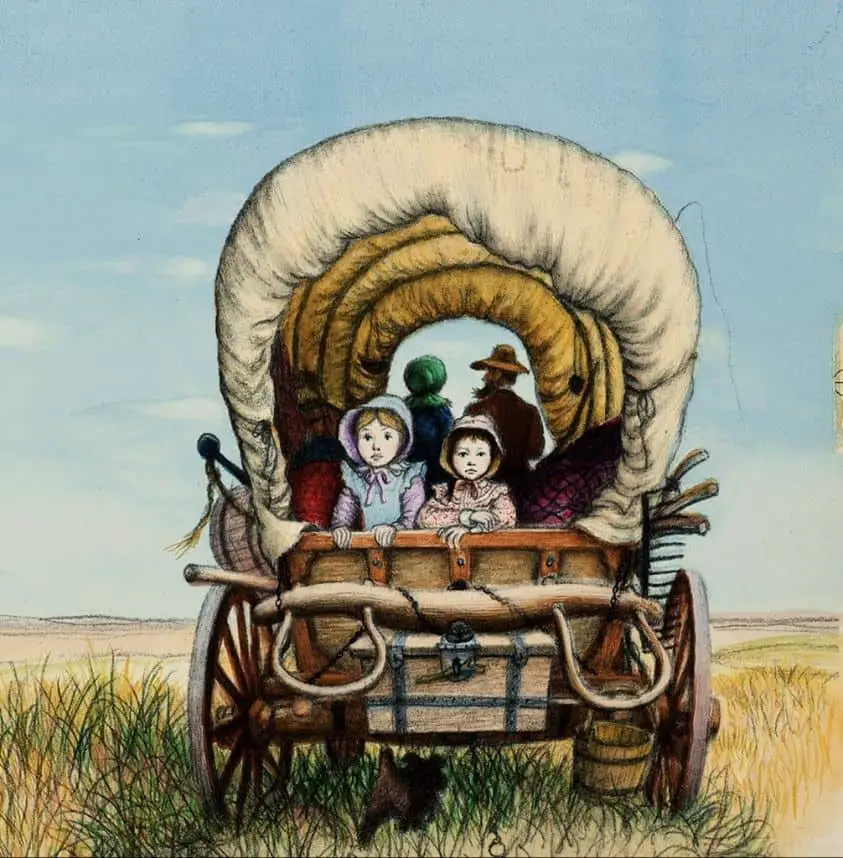

And an arch isn’t always an archway at all. Garth Williams uses the arch in a compositionally similar way to how the artist above drew the audience in the theatre. Two girls, emotionally separate from the parents, but with parents guarding their safety. Though this family occupies the same space, the girls are having a different experience from the adults.

Archways are a common feature in landscape design. Below is an example illustrated by Beatrix Potter.

The garden arches below are functioning more as an umbrella might function, to draw attention to the character, who might otherwise get lost in this busy birds-eye composition.

But the viewer isn’t always meant to notice the arch. Sometimes the arch frames a character. In the illustration below, Thumbelina and the rat each want something different. There’s a border between them. It’s subtle, but it works.

Certain types of bridges make perfect framing arcs.

Fantasy illustrators can find any number of ways to incorporate an arch into composition.

Archways are used in home architecture and interior decoration. The canopy bed also offers a natural arch and framing device. There are many, many examples of canopy beds in art and children’s illustration.

In the comical illustration below, the eye is drawn to the man trying desperately to get out of his parked car. Artist Dick Sargent makes use of the rule of thirds, and intersects the man’s head with the beam of an archway. The archways also insert distance between the man and his car, and the people catching the train. He struggles; they get onto their public transport without fuss.

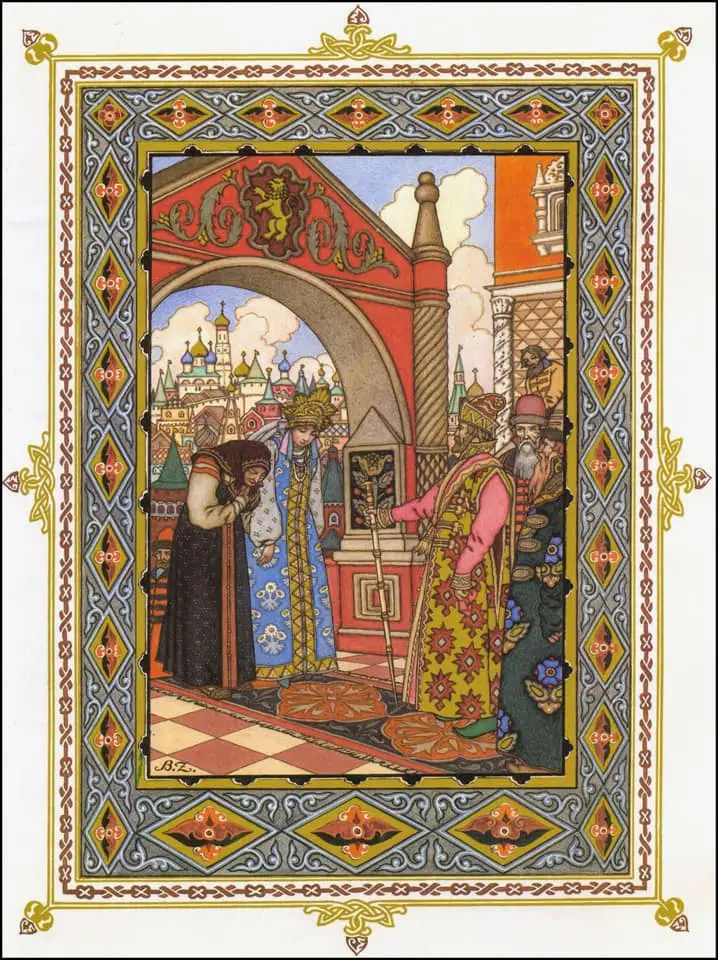

Header illustration by Russian artist Boris Zvorykin (1872-1942)