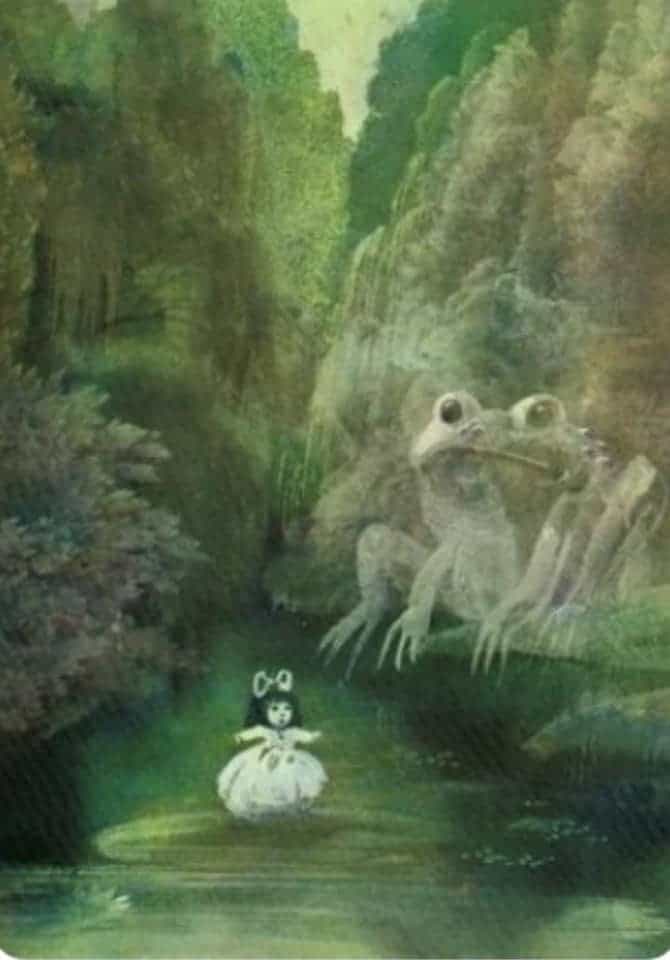

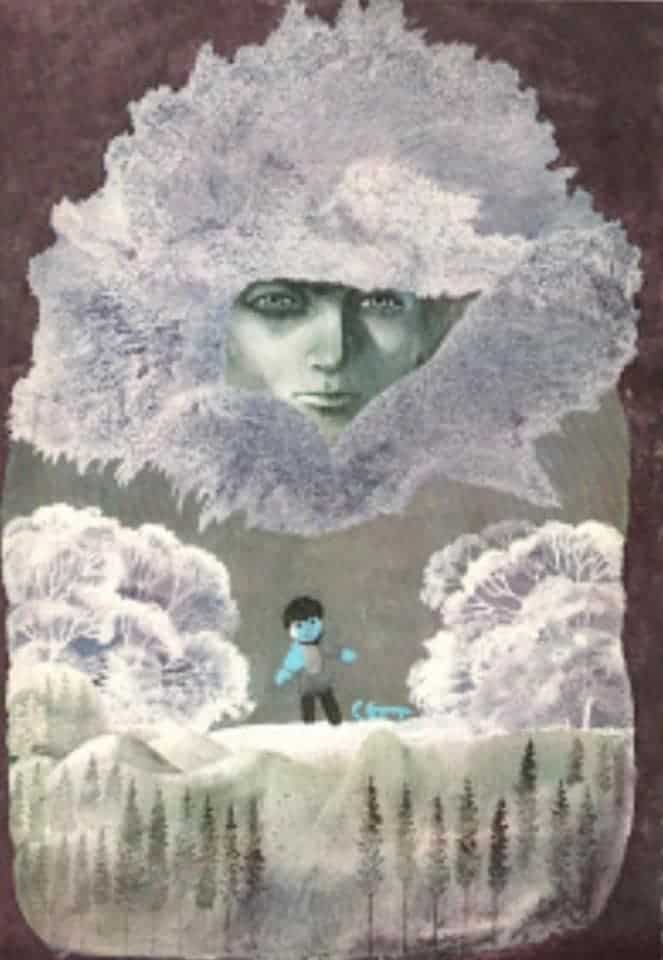

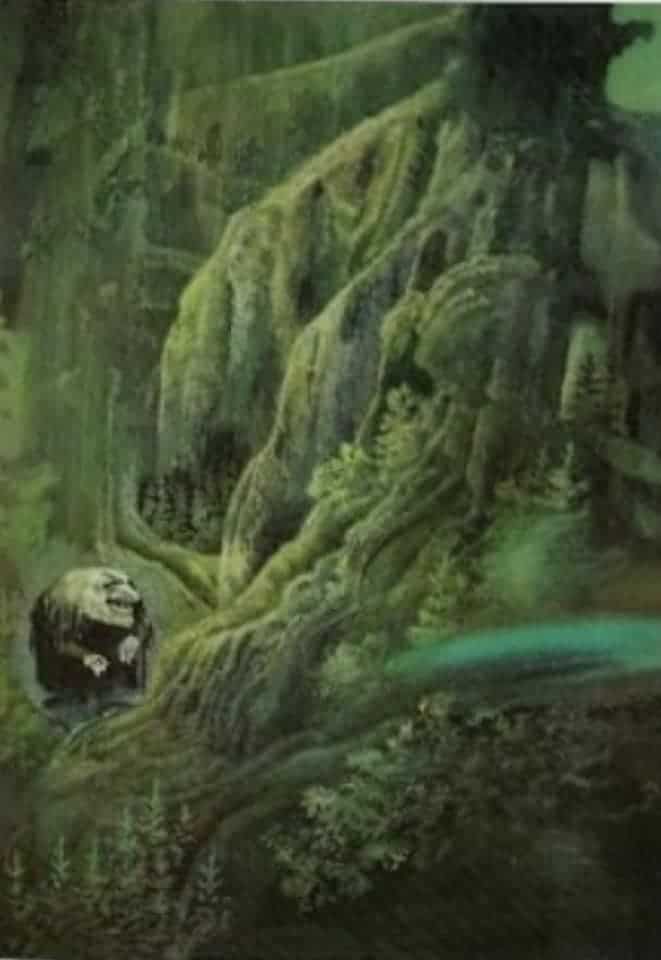

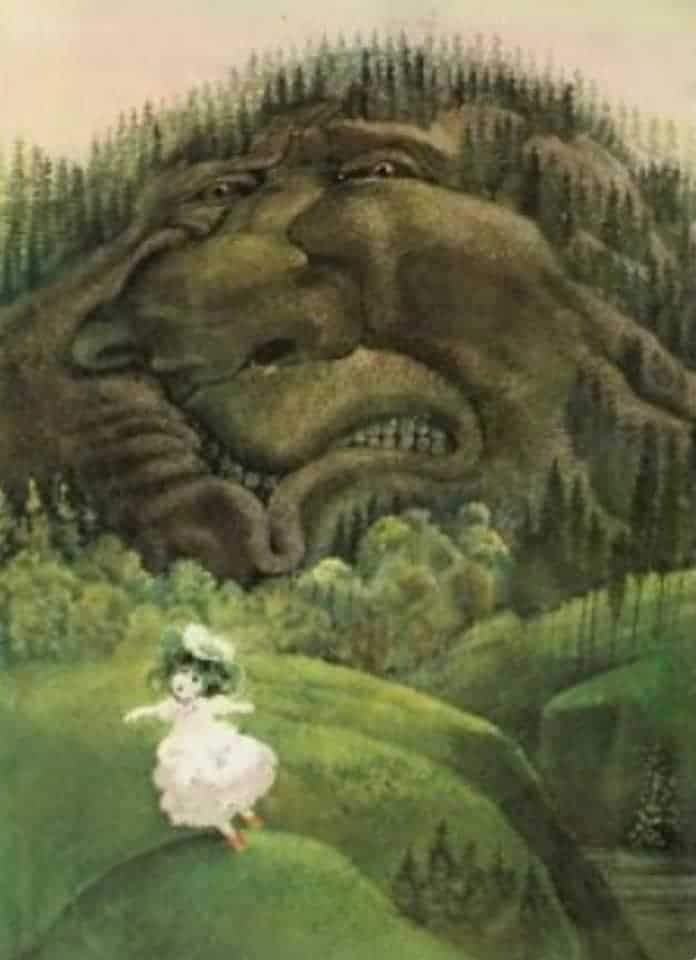

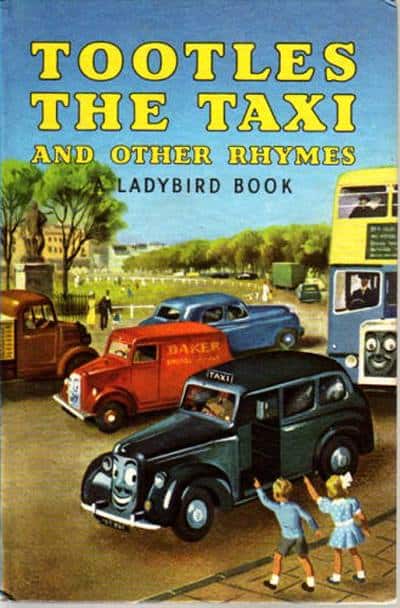

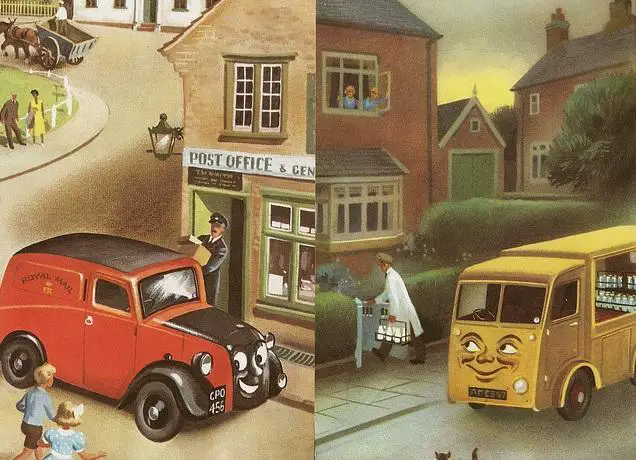

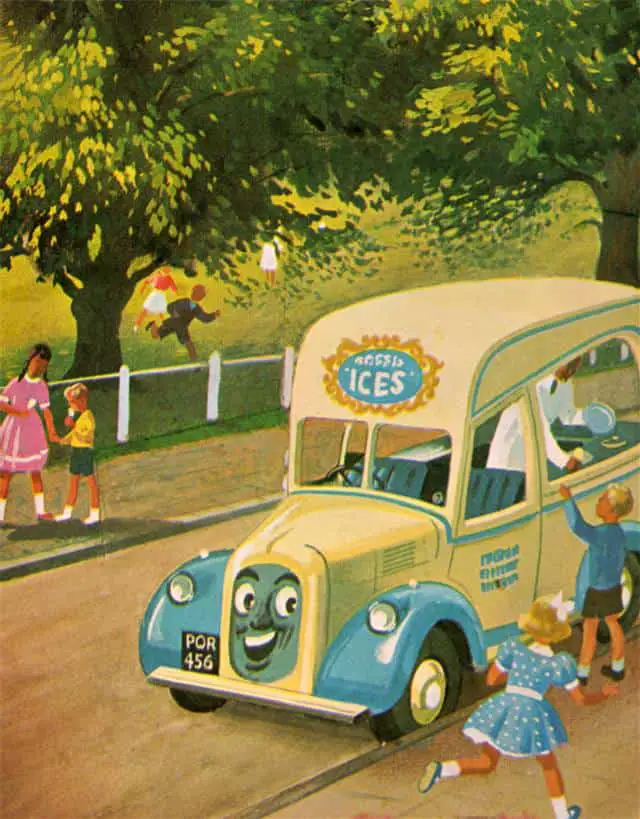

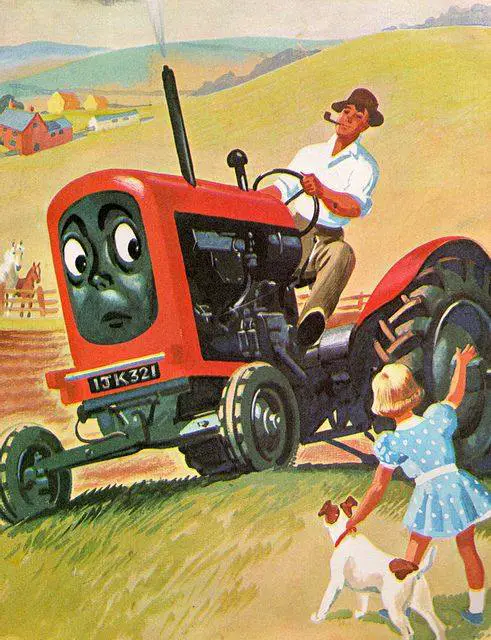

Anthropomorphism is the attribution of human-like characteristics, feelings, and behaviours to non-human characters such as animals, Gods, and supernatural creatures. Anthropomorphism is a similar literary device to personification.

IS THERE A DIFFERENCE BETWEEN PERSONIFICATION AND ANTHROPOMORPHISM?

anthrop = human

morph = shape

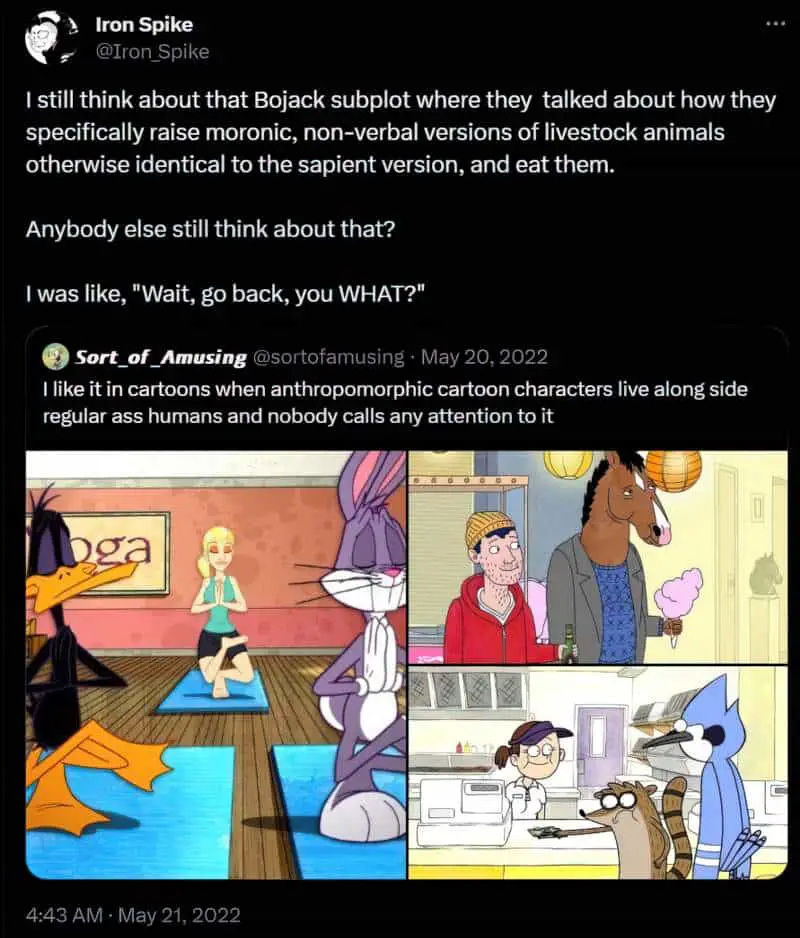

In pop culture the two terms seem to be used interchangeably. See, for instance, 10 Movies That Will Traumatise Your Child With Anthropomorphism from io9.

But some people like to maintain a distinction, despite the overlapping usage. I like this explanation:

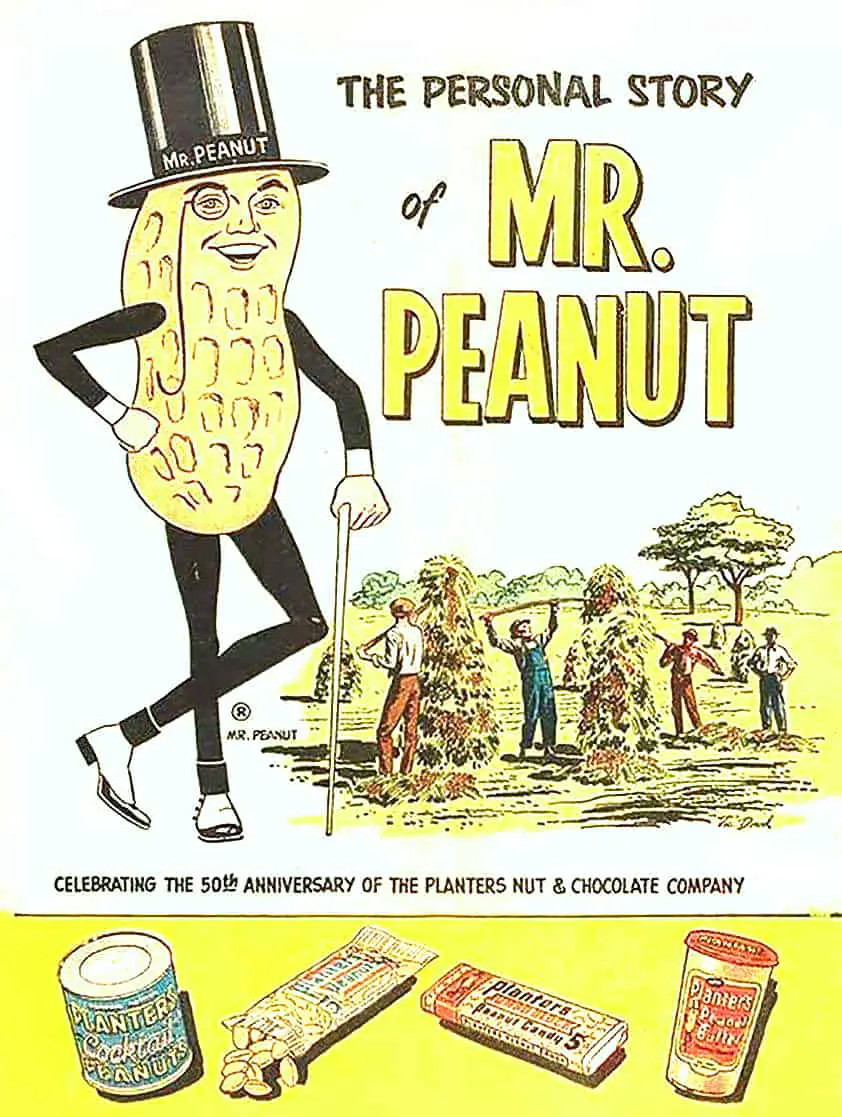

Both personification and anthropomorphization assert intangible human characteristics — such as consciousness and thought — onto an inanimate object, entity or animal. The difference is that anthropomorphization imposes physical or tangible human characteristics onto the subject to suggest an embodiment of the human form.

from the wordreference.com forum

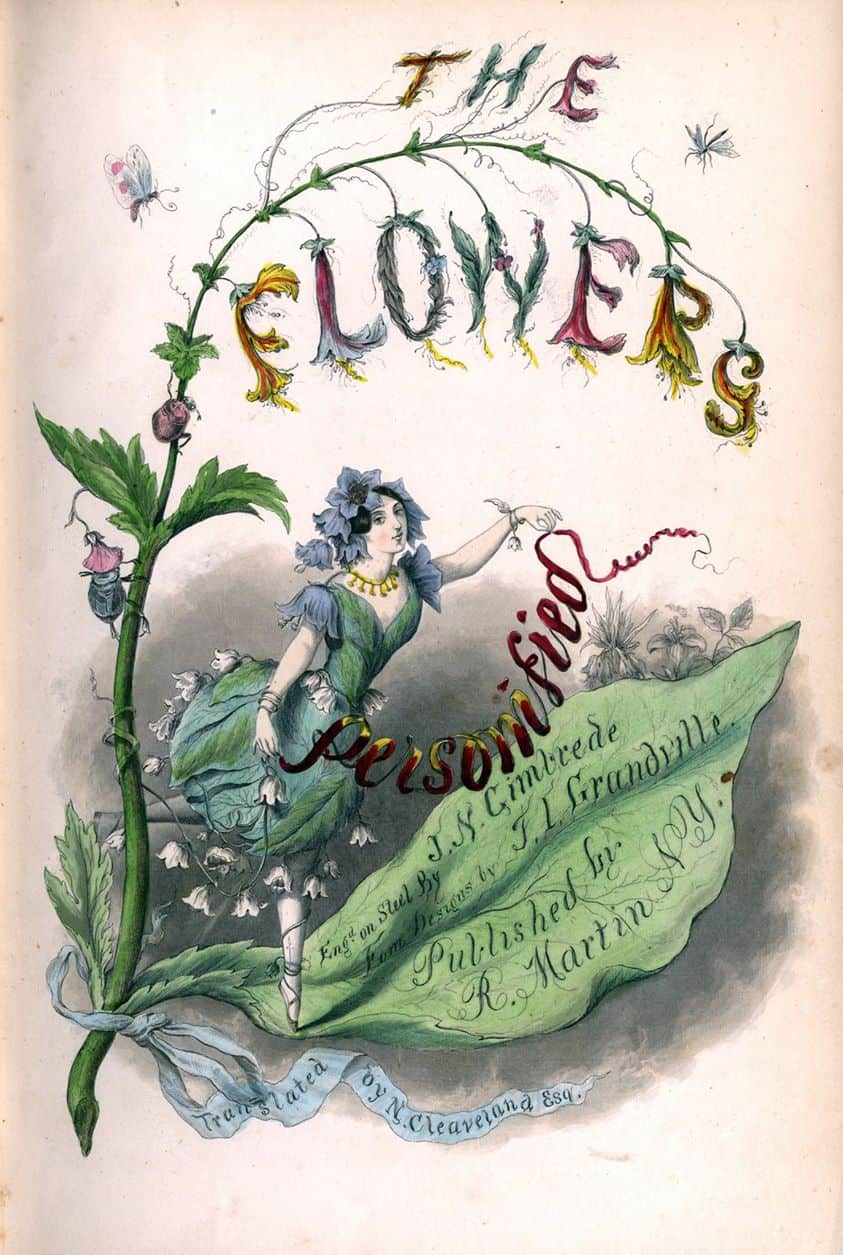

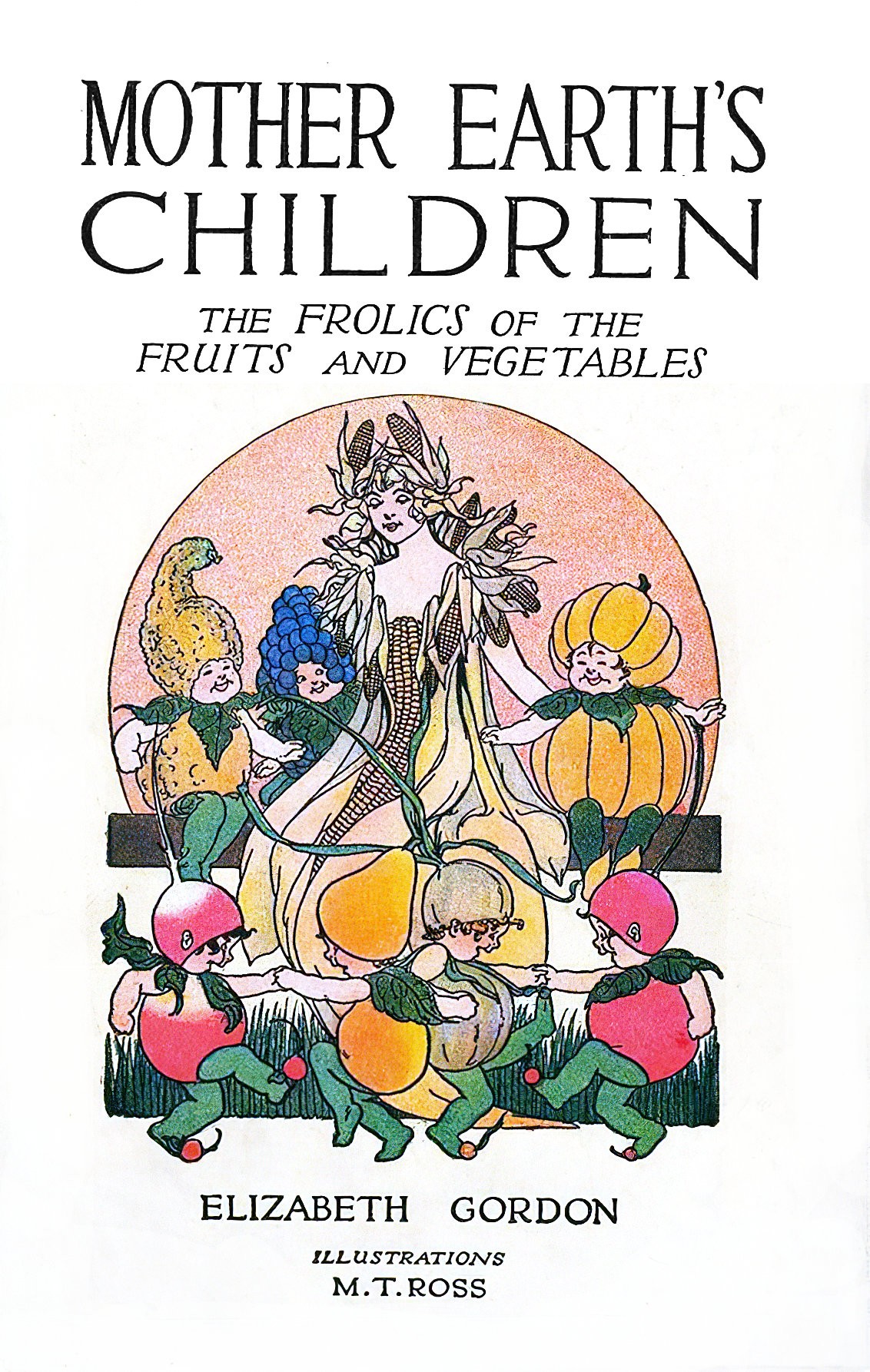

Personification pretends (for literary effect) to ascribe one or two human attributes (especially thoughts, feelings, intentions) to non-human things.

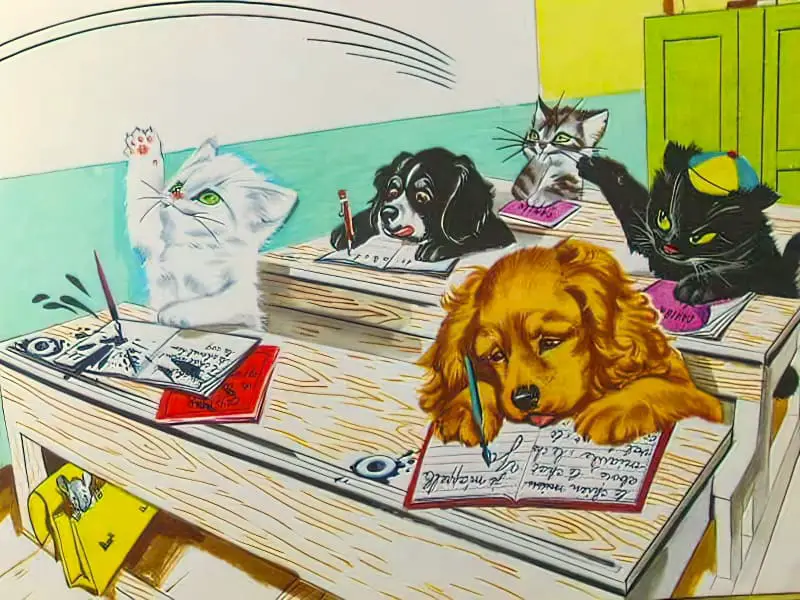

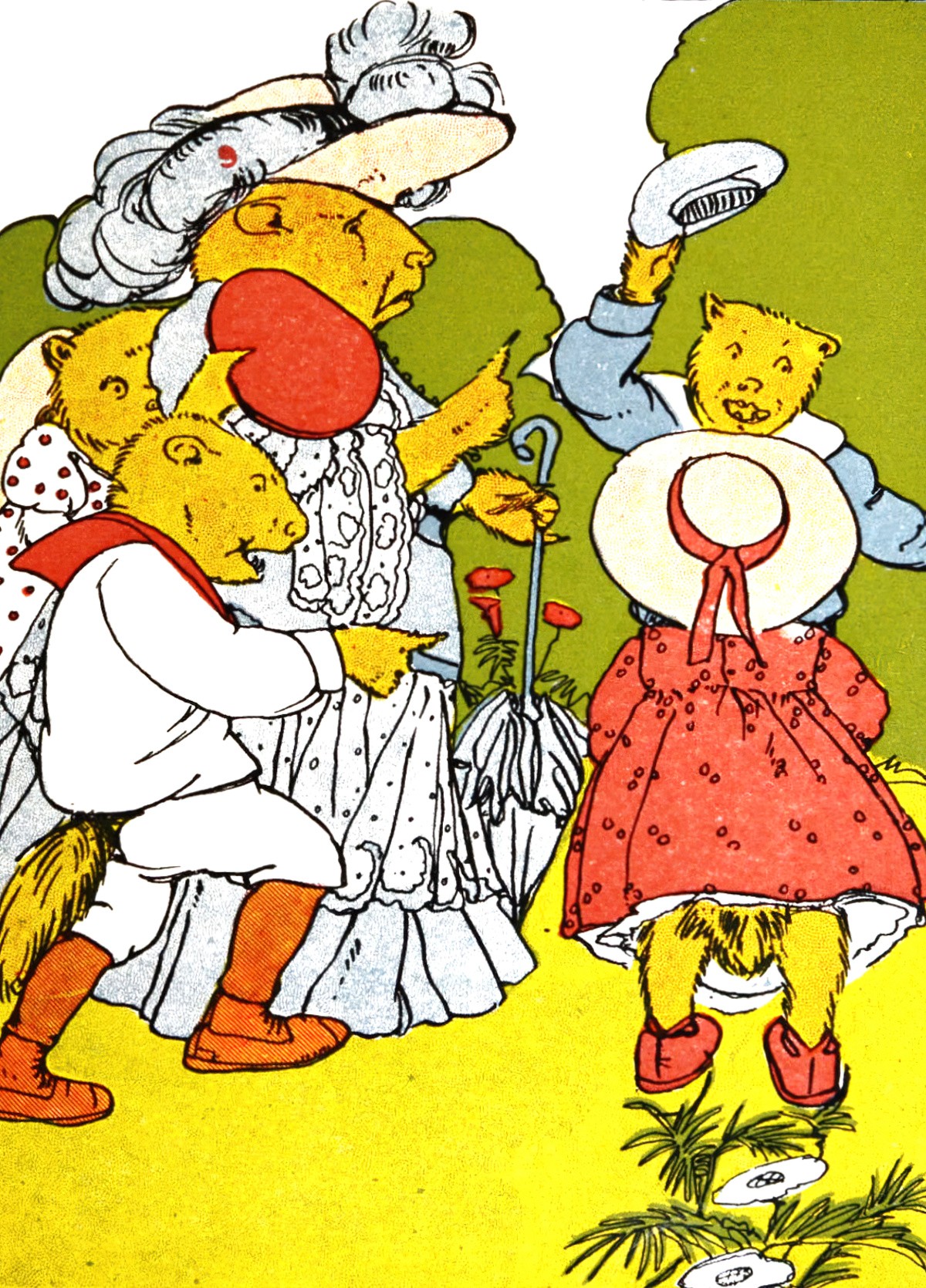

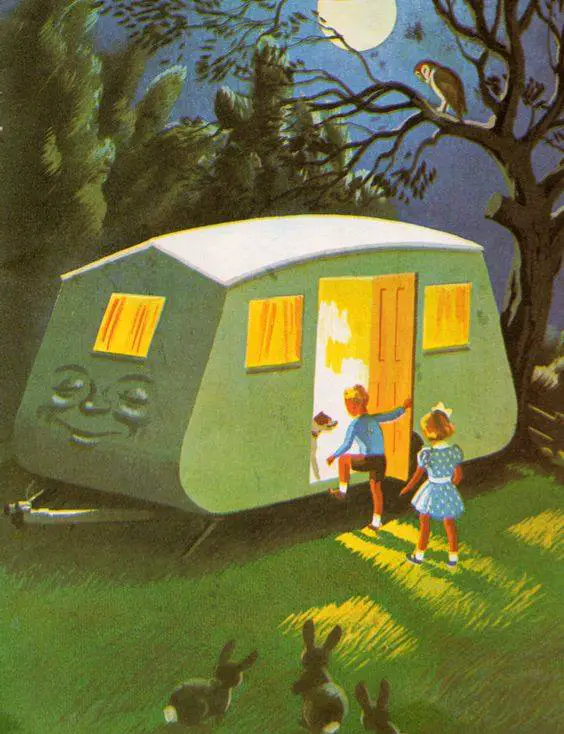

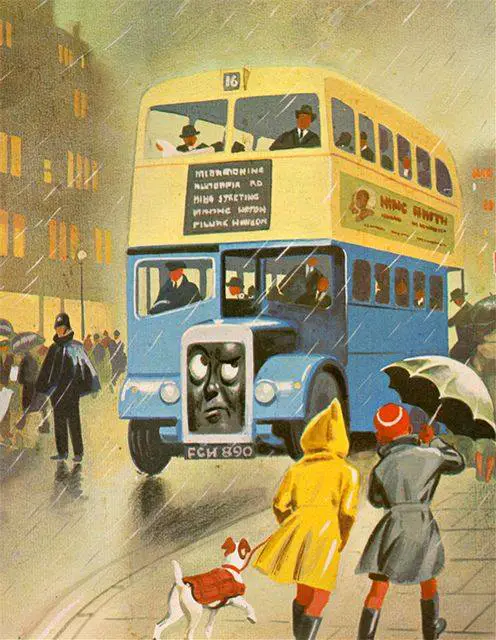

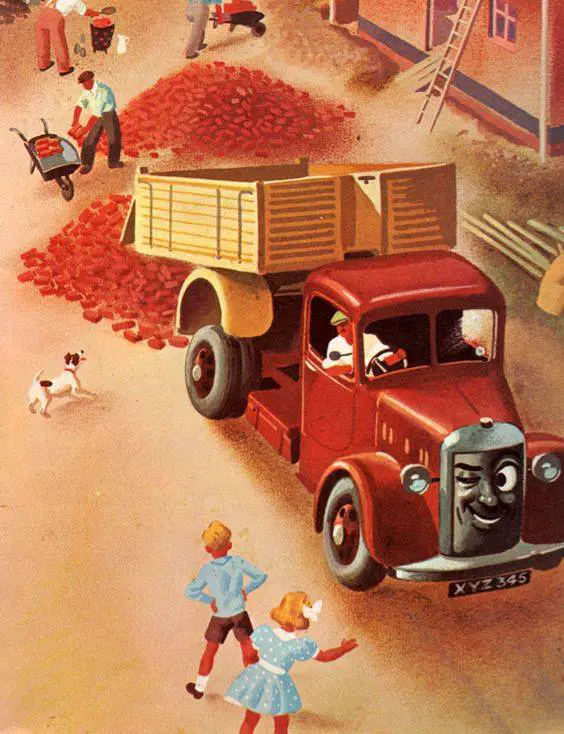

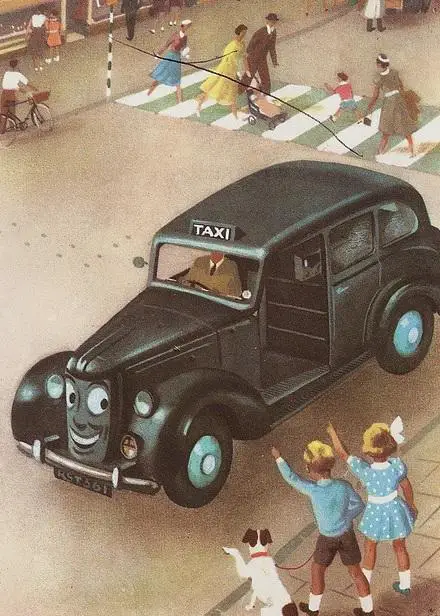

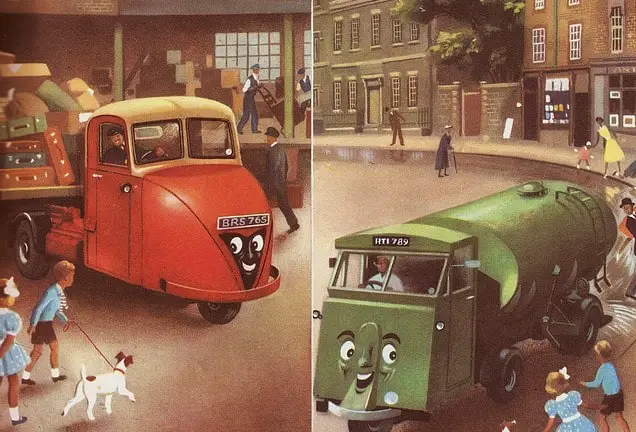

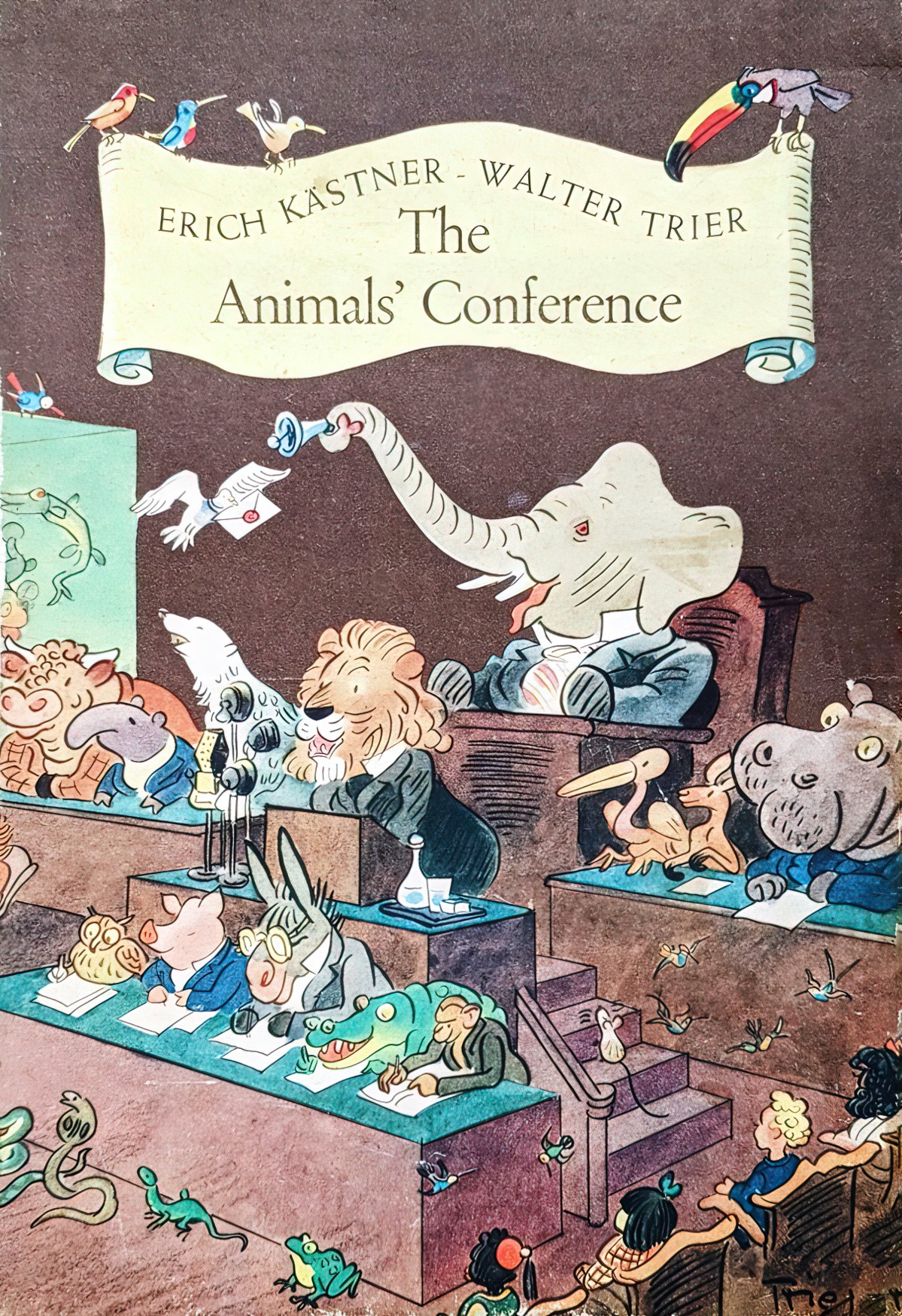

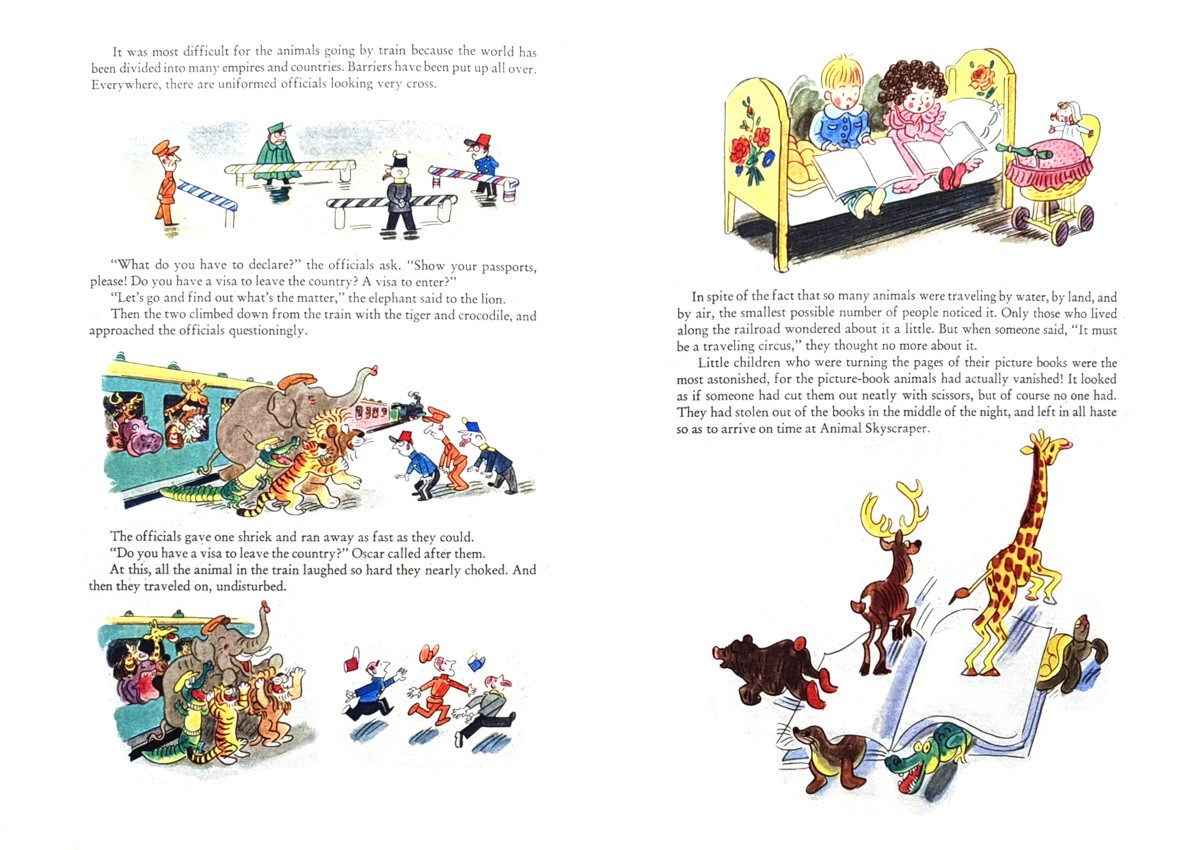

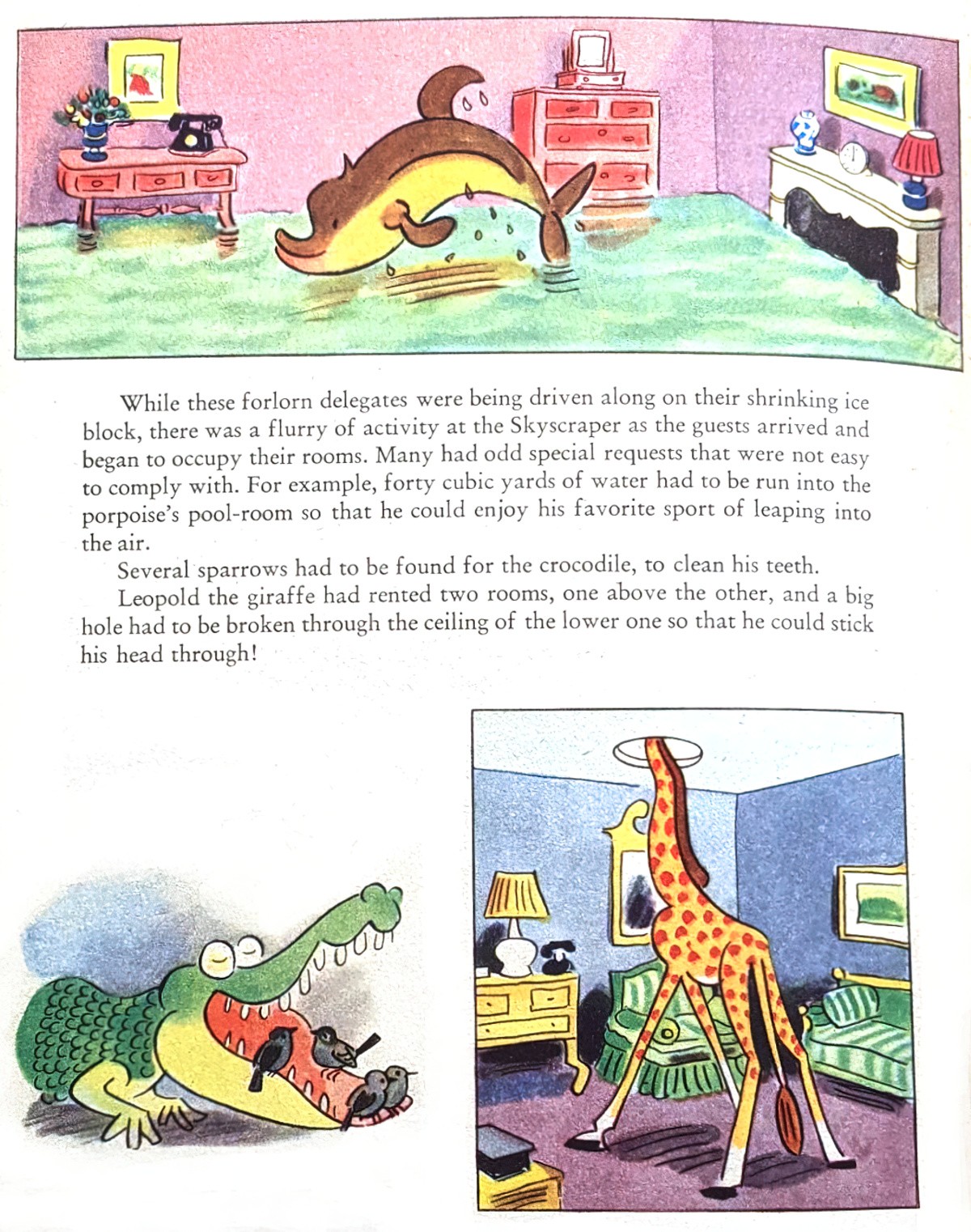

Anthropomorphism turns non-humans into humans completely — such as Bugs Bunny, the animals of Aesop’s fables, the three bears who chased Goldilocks, or the Uncle Remus characters.

Another way of looking at anthropomorphism is that it is actually talking about humans — but pretends that they are shaped like animals.

This is a popular device in children’s literature, fairy tales, and comic strips. One benefit is that the characters don’t have any race or gender, so all children everywhere can identify with them. [For more on that see Why So Many Animals In Picturebooks?]

from someone at Yahoo answers.

FOR FURTHER INVESTIGATION

Dogs Are People, Too, an archived New Yorker video

an other BY Sharon Patricia Holland

In an other: a black feminist examination of animal life (Duke UP, 2023), Sharon Patricia Holland offers a new theorization of the human animal/divide by shifting focus from distinction toward relation in ways that acknowledge that humans are also animals. Holland centers ethical commitments over ontological concerns to spotlight those moments when Black people ethically relate with animals. Drawing on writers and thinkers ranging from Hortense Spillers, Sara Ahmed, Toni Morrison, and C. E. Morgan to Jane Bennett, Jacques Derrida, and Donna Haraway, Holland decenters the human in Black feminist thought to interrogate blackness, insurgence, flesh, and femaleness. She examines MOVE’s incarnation as an animal liberation group; uses sovereignty in Morrison’s A Mercy to understand blackness, indigeneity, and the animal; analyzes Charles Burnett’s films as commentaries on the place of animals in Black life; and shows how equestrian novels address Black and animal life in ways that rehearse the practices of the slavocracy. By focusing on doing rather than being, Holland demonstrates that Black life is not solely likened to animal life; it is relational and world-forming with animal lives.

New Books Network