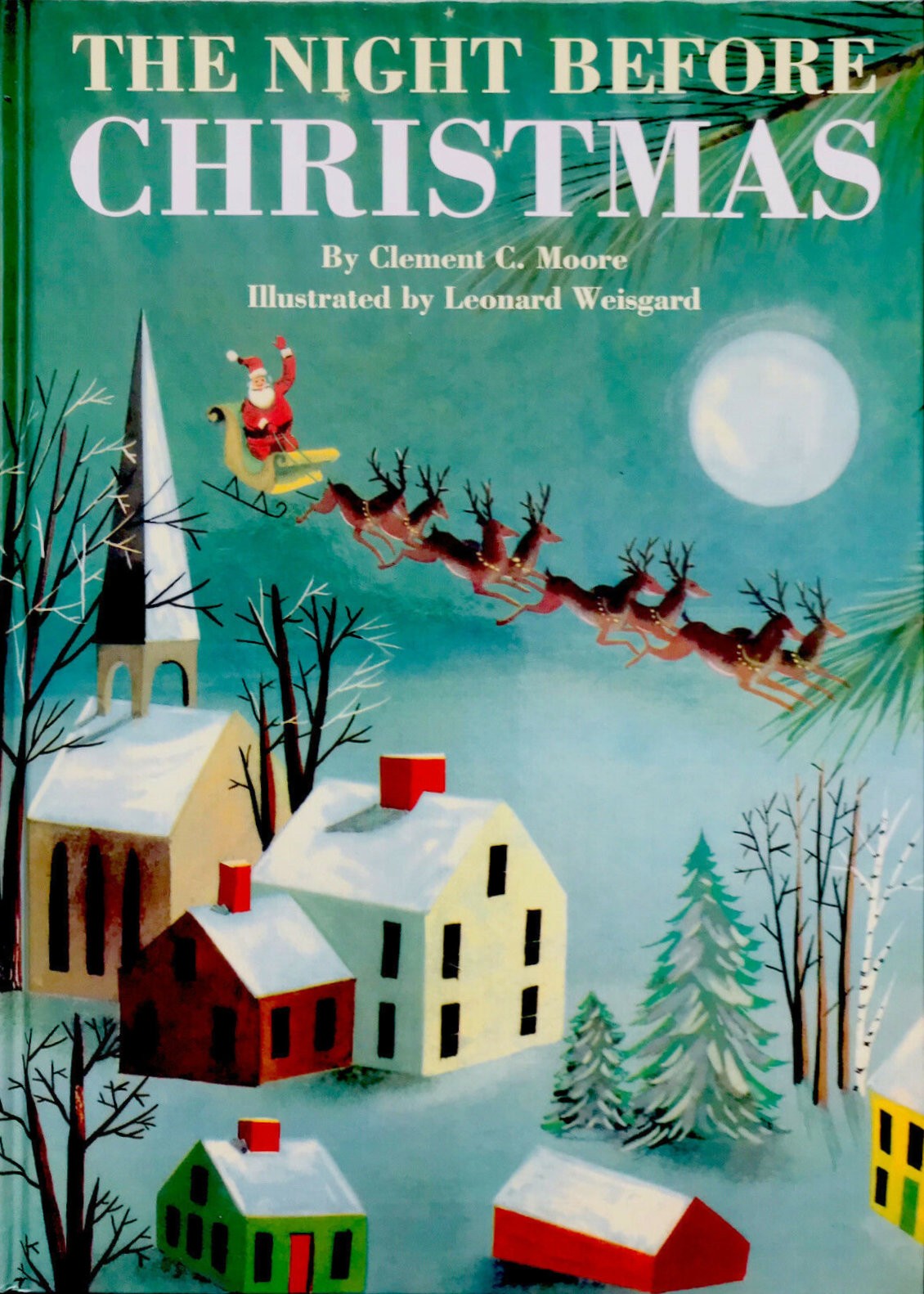

“The Night Before Christmas” is an alternative title of the poem “A Visit from St. Nicholas” (controversially) by a guy called Clement Clarke Moore. The poem was first published anonymously in 1823 and only later attributed to Clement Clarke Moore, who claimed authorship in 1837, the start of the Victorian era. A Dutch migrant called Henry Livingston might be the true author. We don’t know.

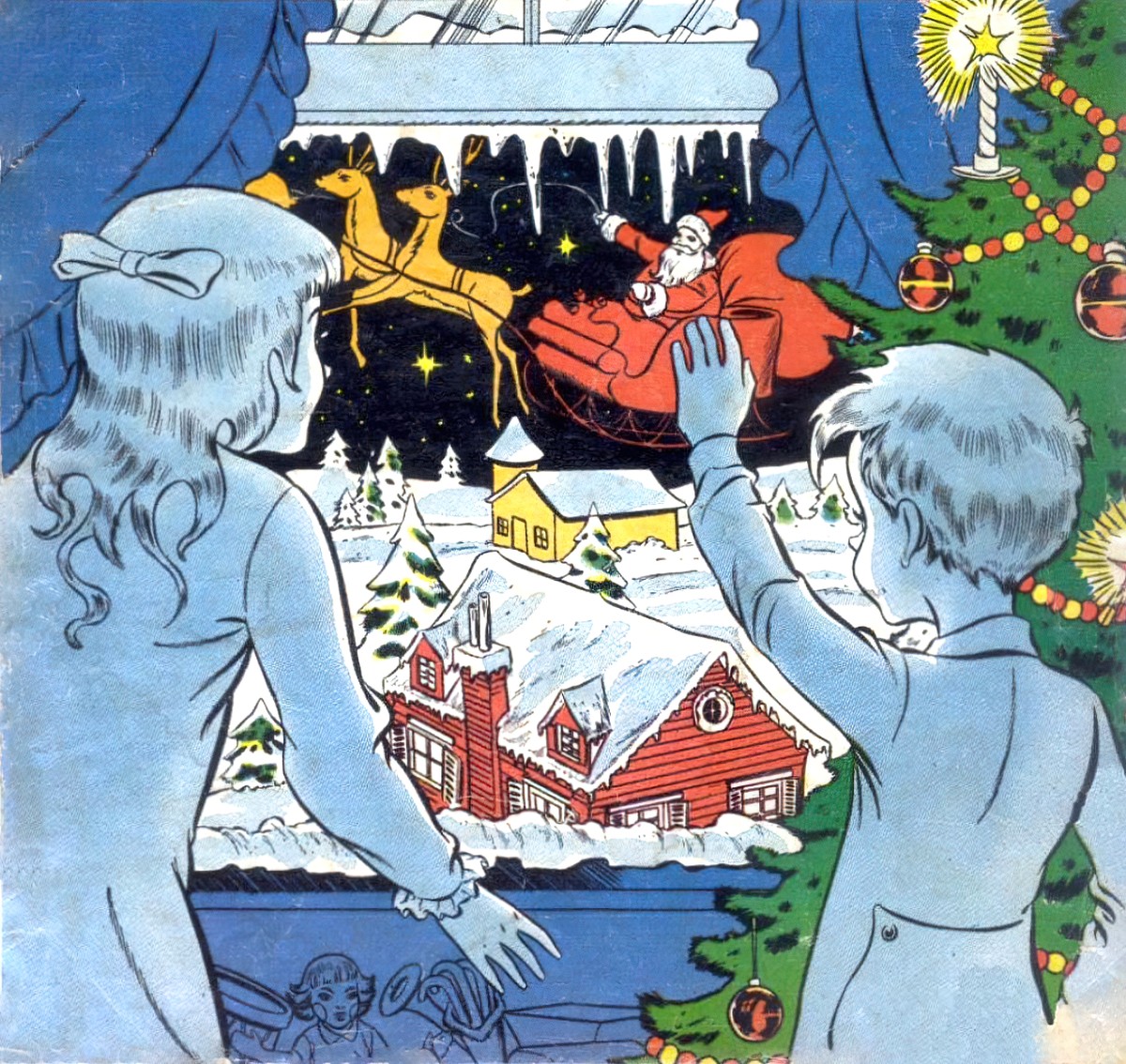

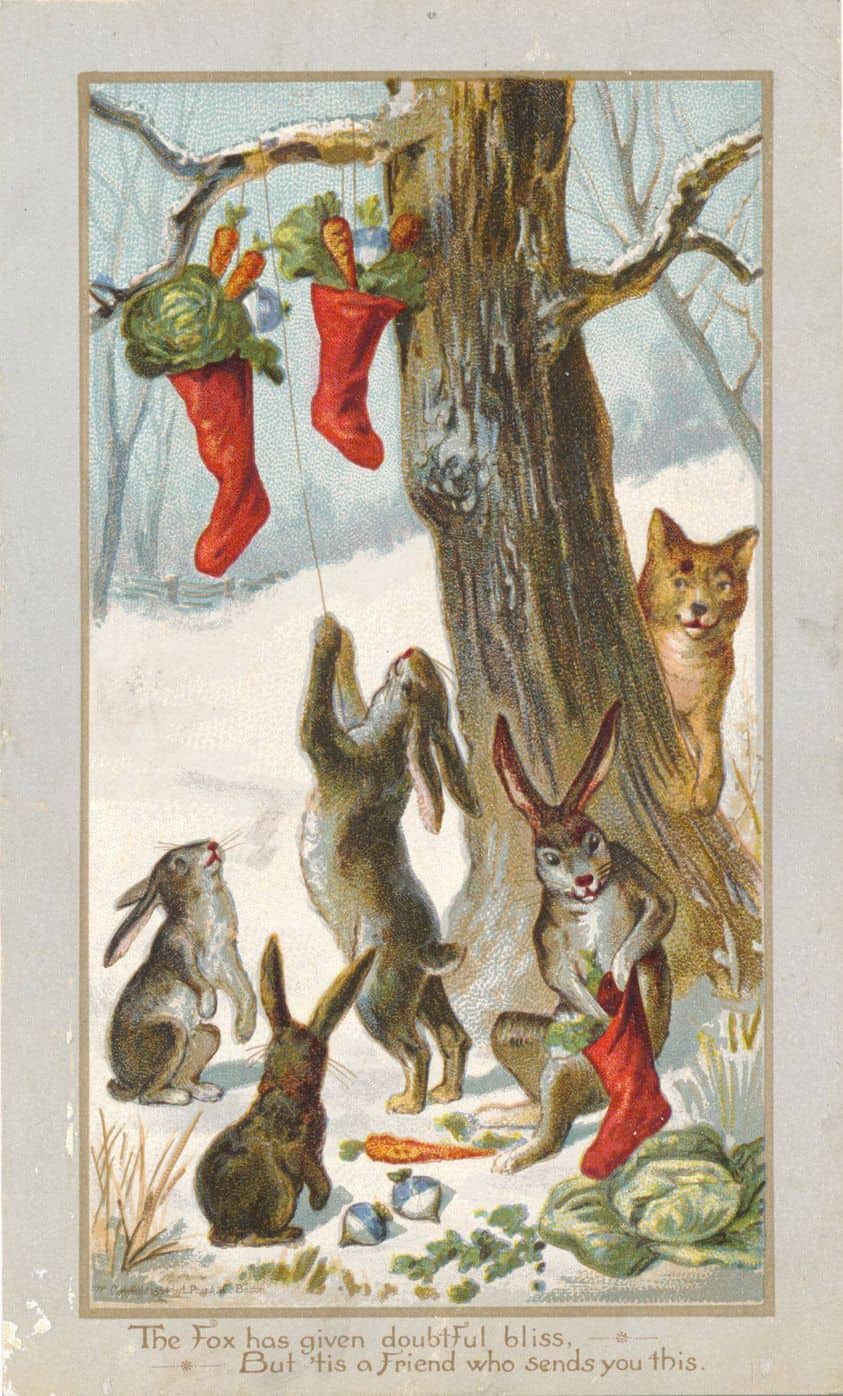

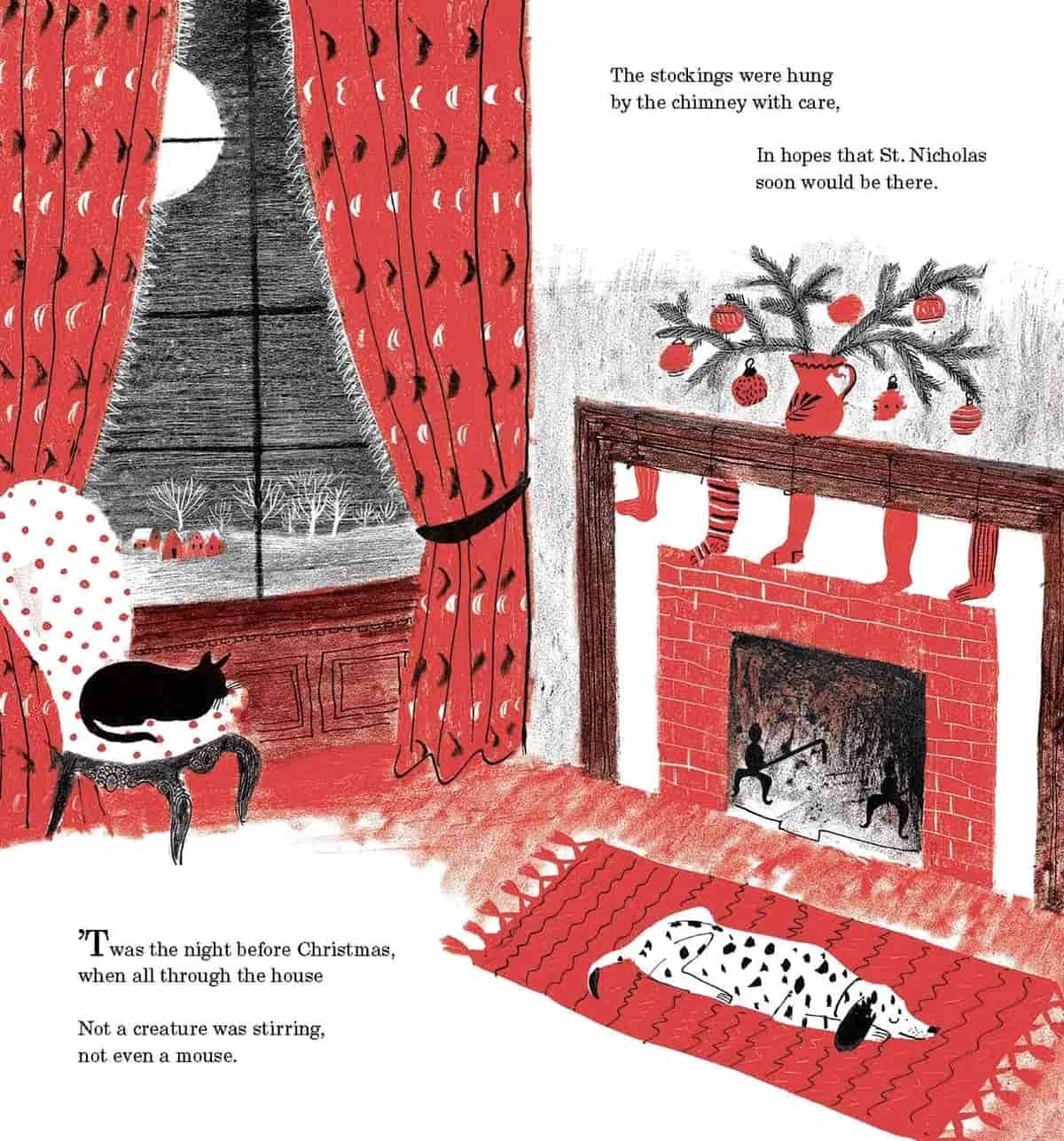

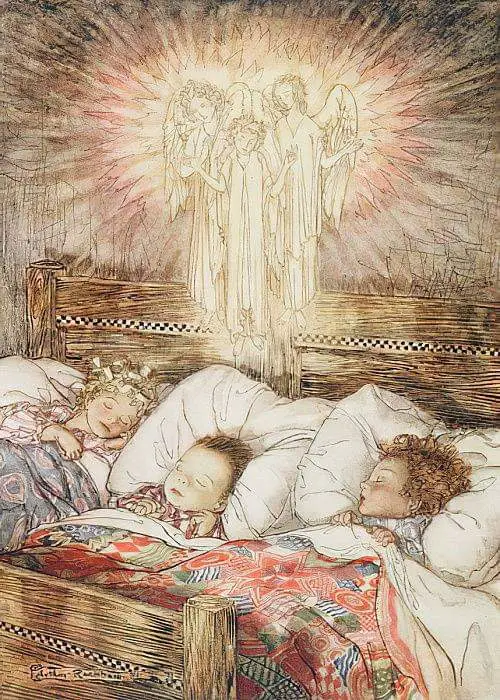

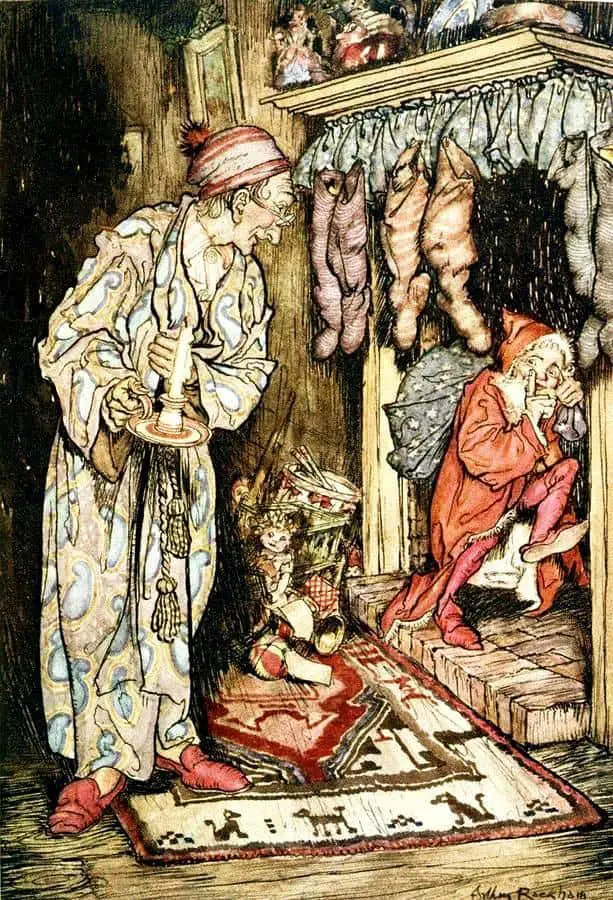

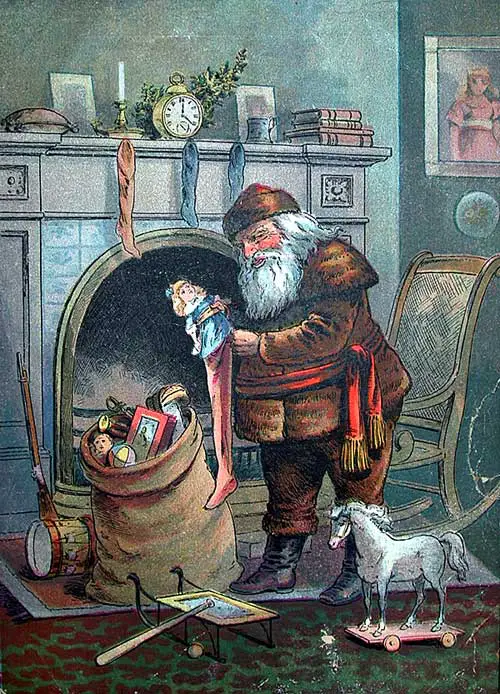

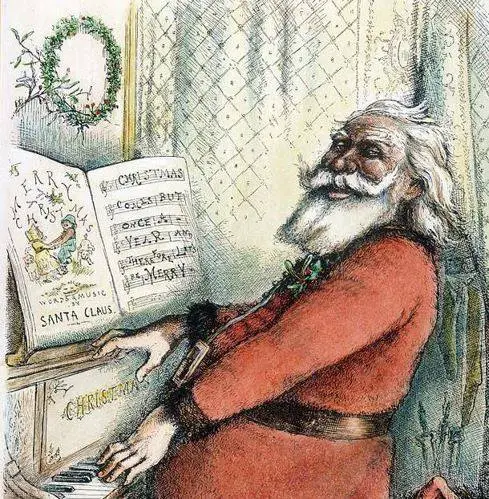

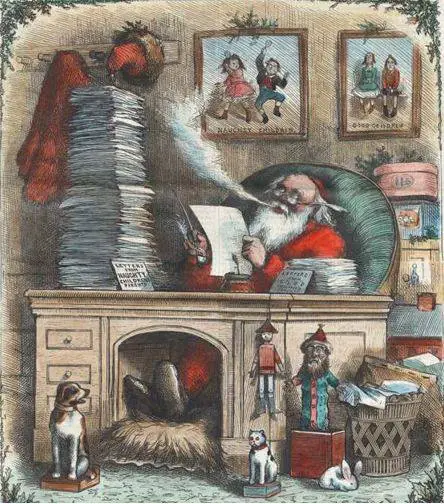

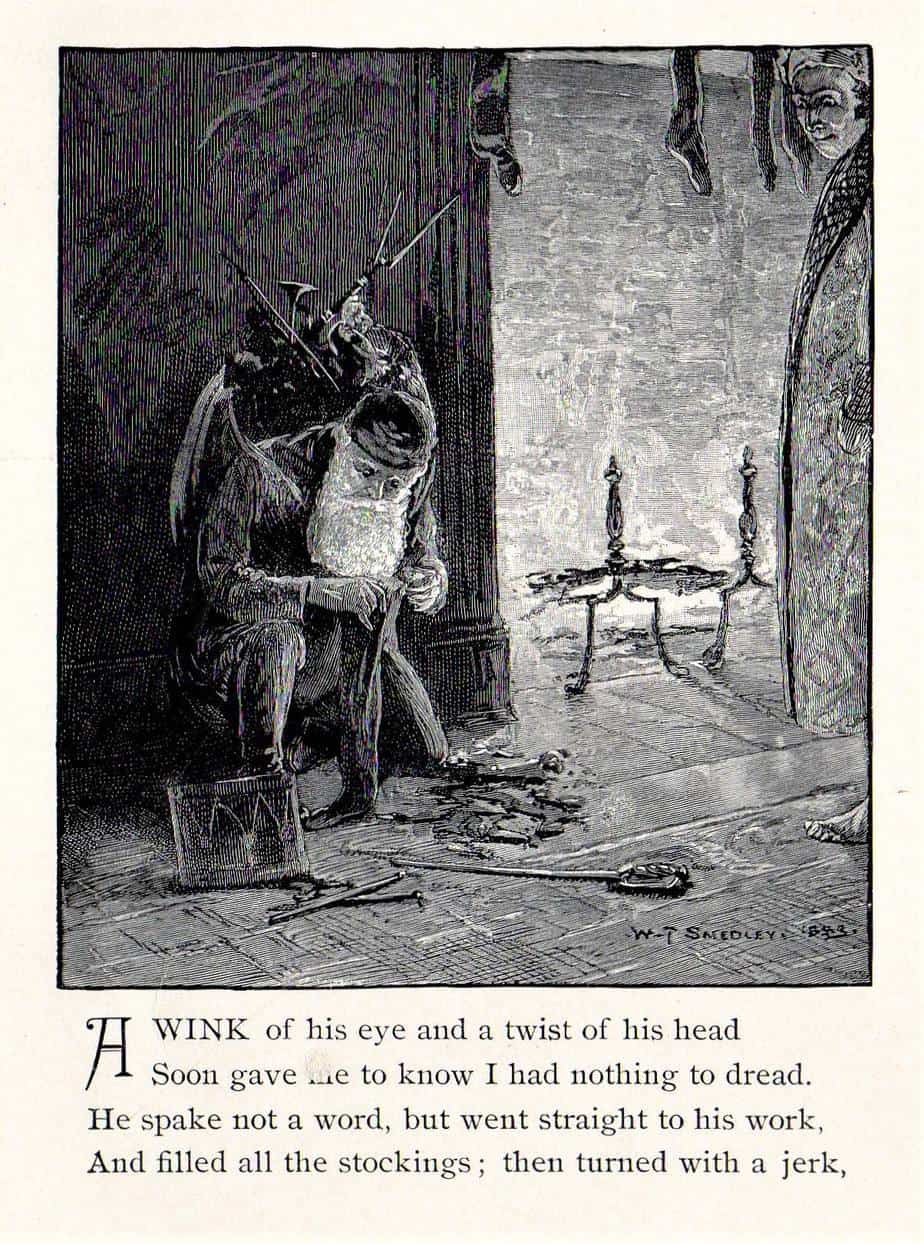

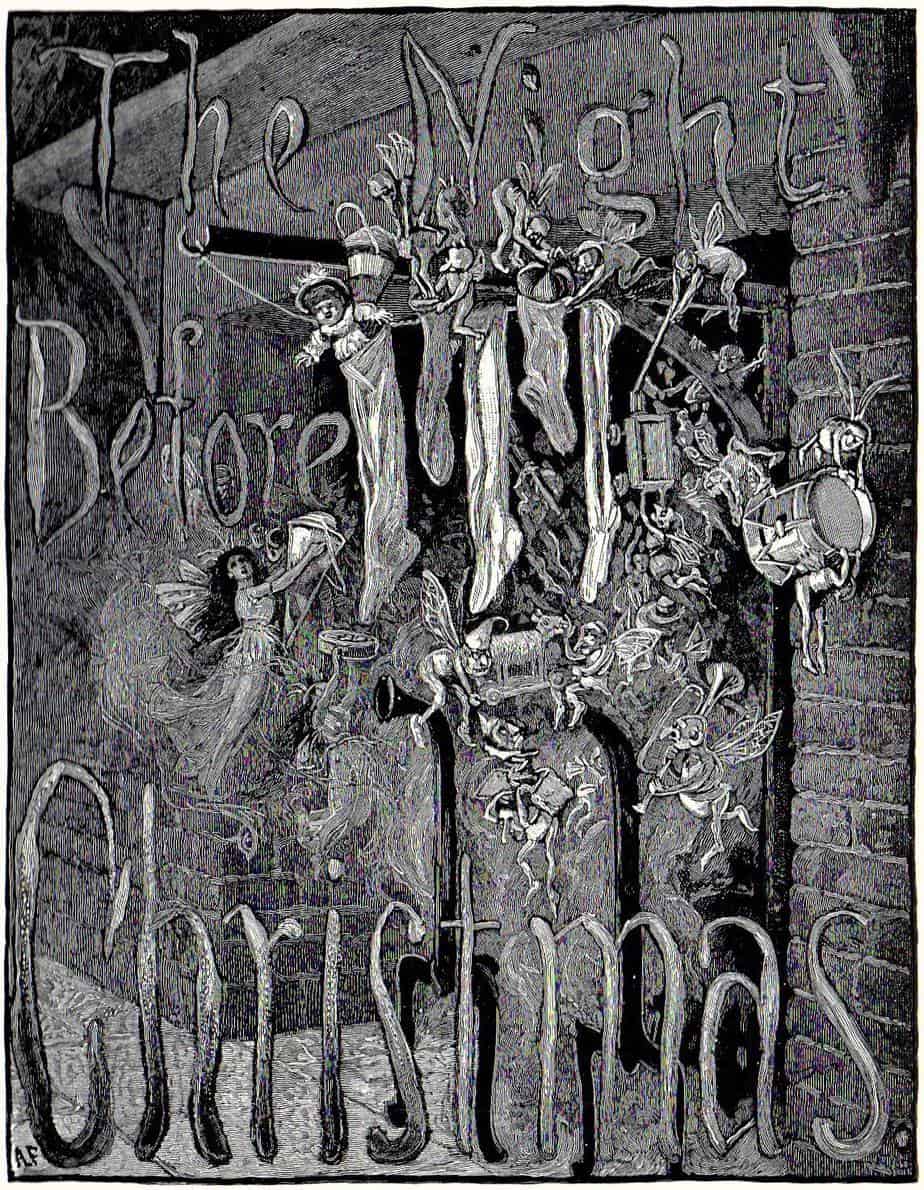

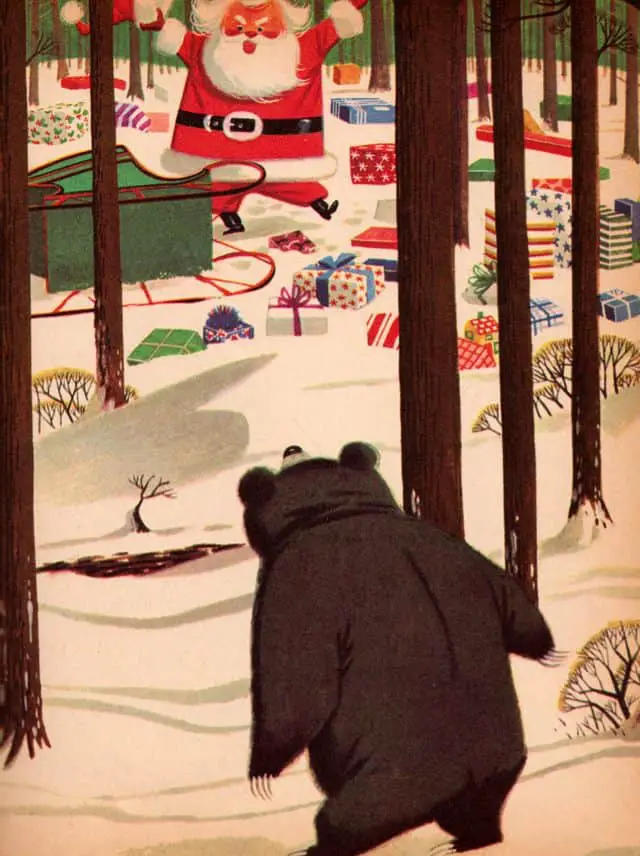

Many Victorian illustrations were pretty grim, even those meant for Christmas. Take a look at this one:

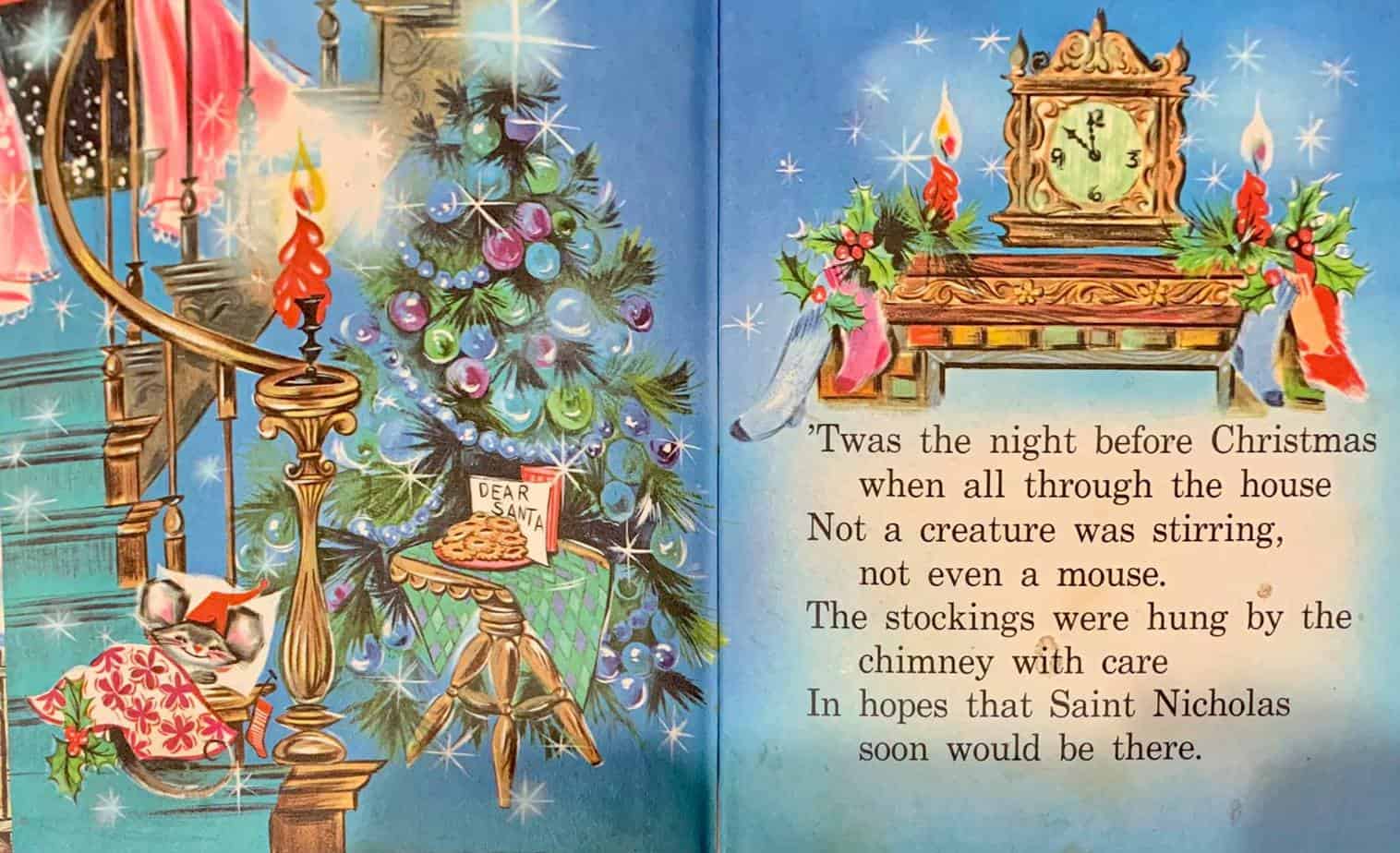

‘Twas the night before Christmas, when all through the house

Not a creature was stirring, not even a mouse;

The stockings were hung by the chimney with care,

In hopes that St. Nicholas soon would be there;

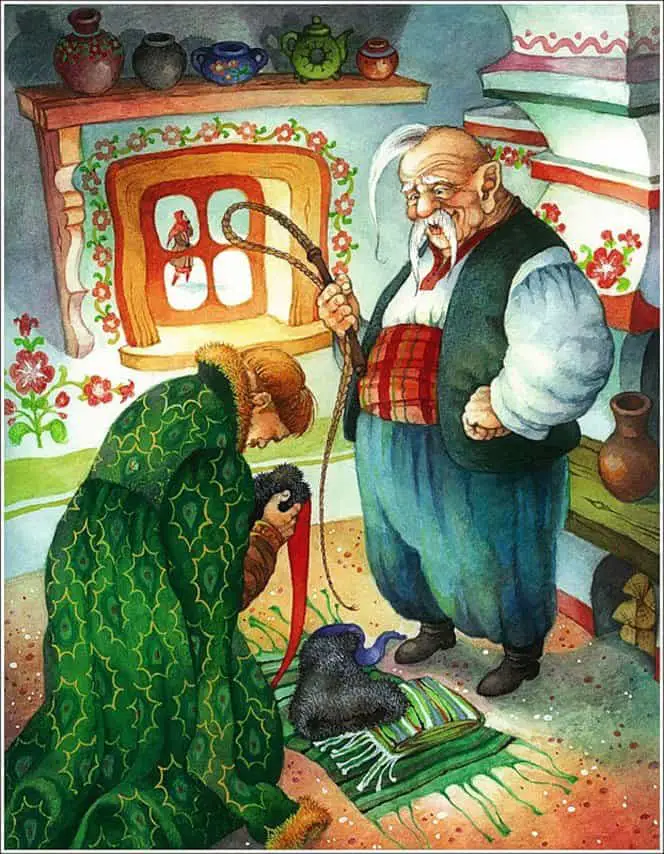

In some cultures, it is still a witch-like creature who brings the presents eg. Italy. (It makes more sense to me that a woman would be doing the bulk of the work of Christmas.)

Why stockings?

A recently widowed man and father of three girls was having a tough time making ends meet. Even though his daughters were beautiful, he worried that their impoverished status would make it impossible for them to marry. St. Nicholas was wandering through the town where the man lived and heard villagers discussing that family’s plight. He wanted to help but knew the man would refuse any kind of charity directly. Instead, one night, he slid down the chimney of the family’s house and filled the girls’ recently laundered stockings, which happened to be drying by the fire, with gold coins. And then he disappeared. The girls awoke in the morning, overjoyed upon discovering the bounty. Because of St. Nick’s generosity, the daughters were now eligible to wed and their father could rest easy that they wouldn’t fall into lonely despair.

The Smithsonian

That story is from an era in which a girl’s only aim in life is to find a husband (or risk abject loneliness forever) and in which it’s not considered creepy for an old man to be riffling through young women’s laundry.

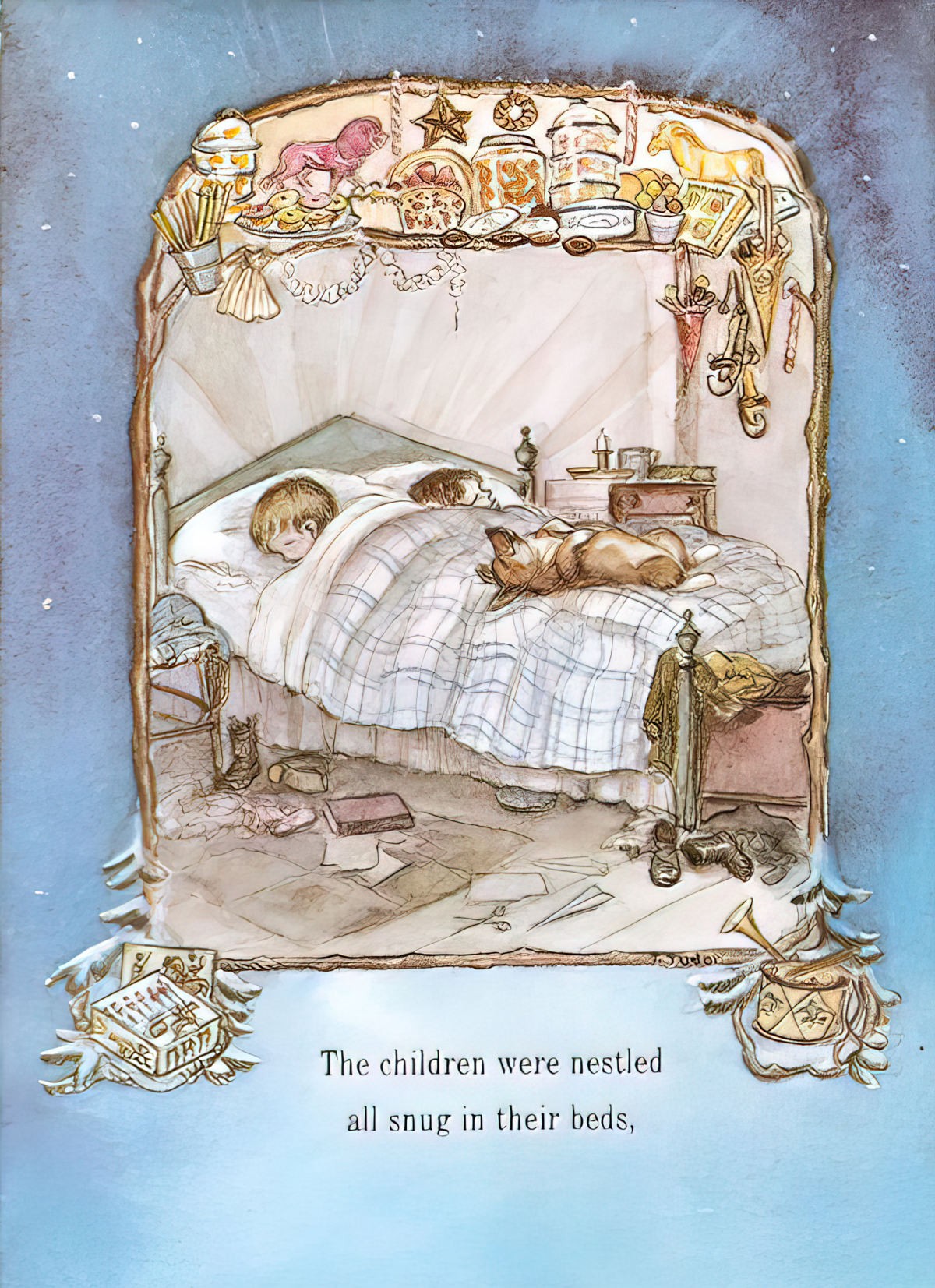

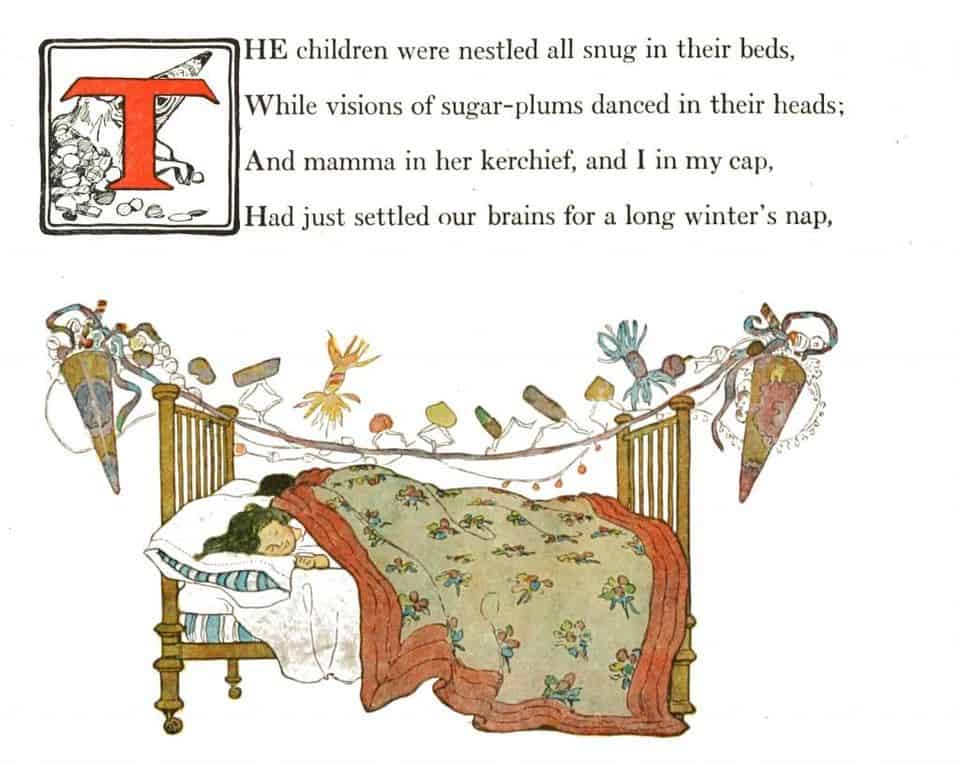

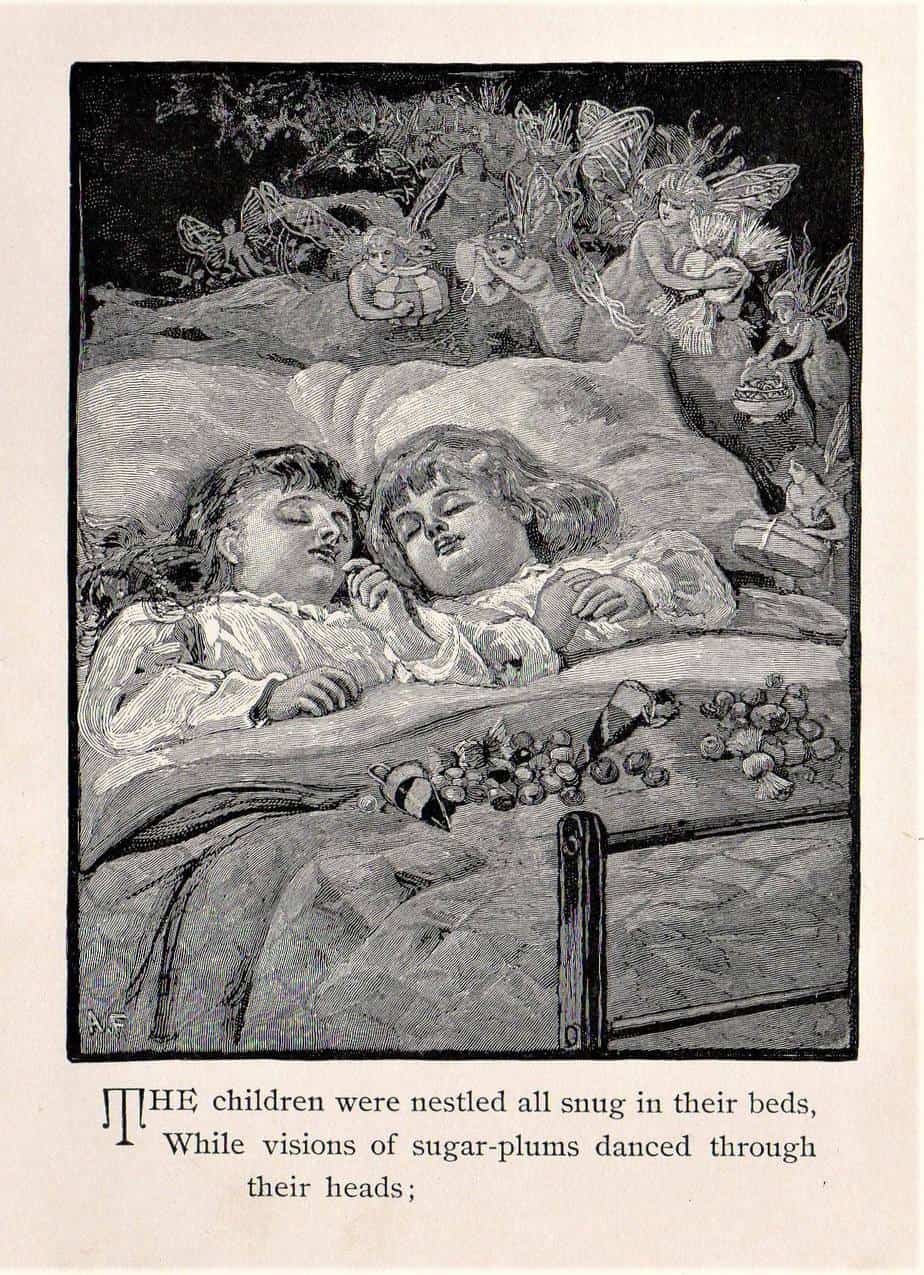

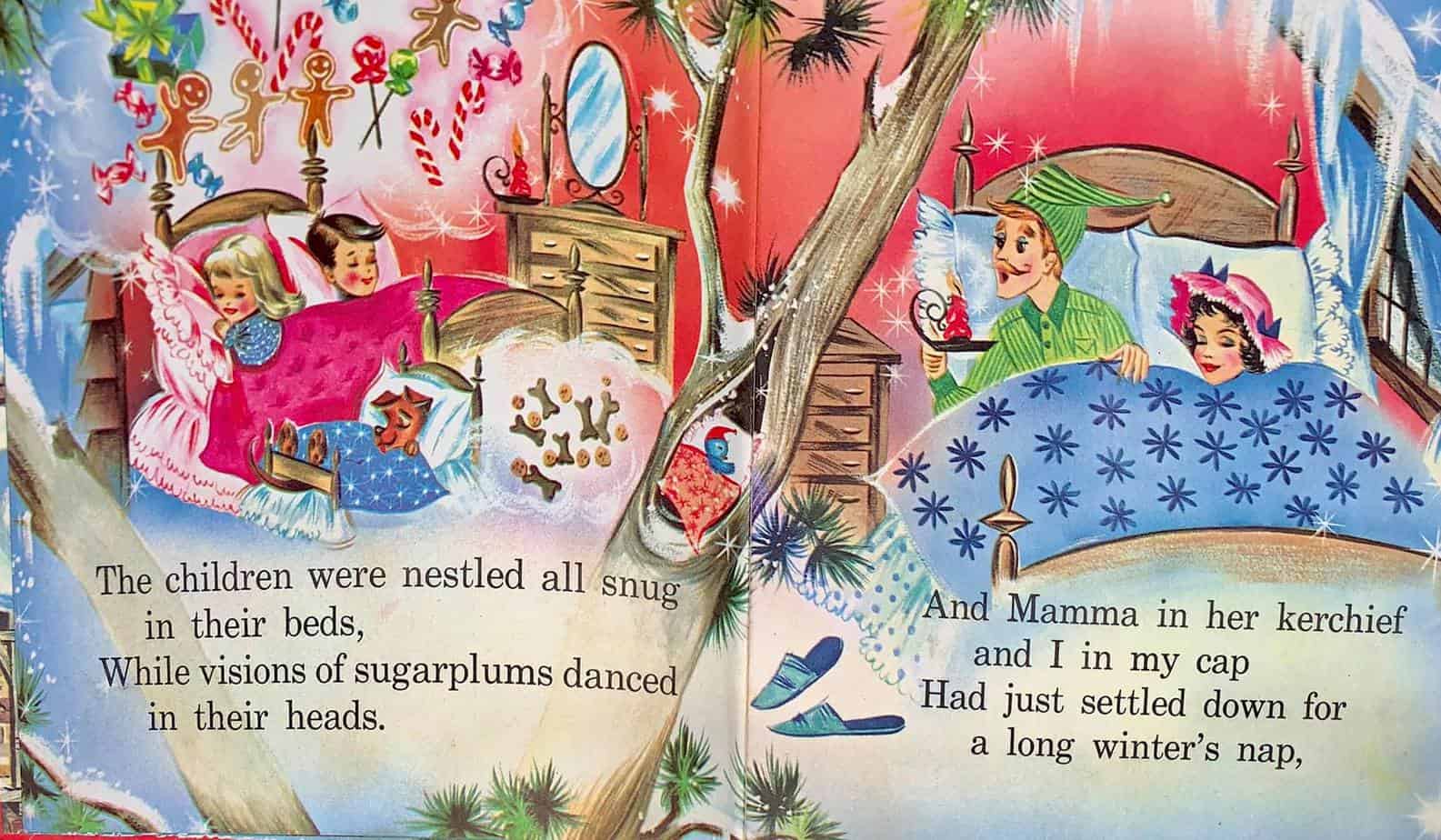

The children were nestled all snug in their beds,

While visions of sugar-plums danced in their heads;

And mamma in her ‘kerchief, and I in my cap,

Had just settled down for a long winter’s nap,

The poem is revealed to have a narrator — a father.

Sugar Plums are not plums covered in sugar. They are a dried fruit, nut and spice mixture pulverized into small balls rolled in coarse sugar.

“While visions of sugarplums danced in their heads…” But, what exactly is a sugarplum? On the season finale of A Taste of the Past, Linda Pelaccio is in studio with Michael Krondl and Cathy Kaufman discussing the history behind the sweets enjoyed throughout the holidays. Embarking on a great fruitcake debate, explaining the plethora of sweeteners used throughout the ages, as well as the origins of the infamous yule log and more, this episode covers it all!

Sugarplums and Gingerbread: A History of Christmas Sweets

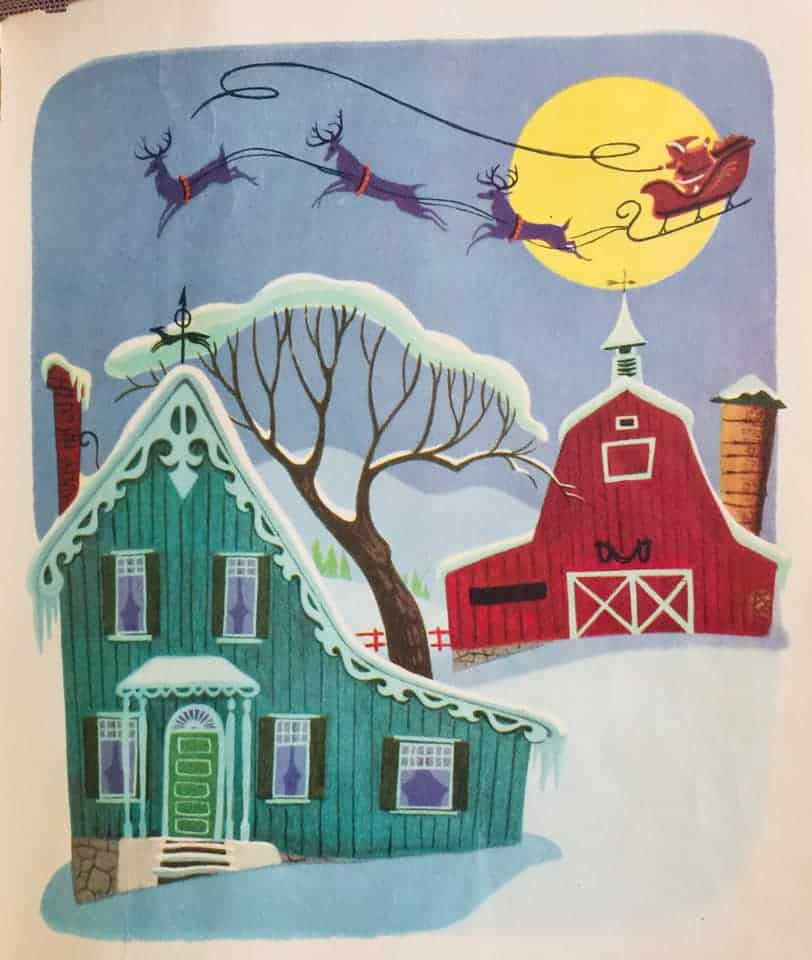

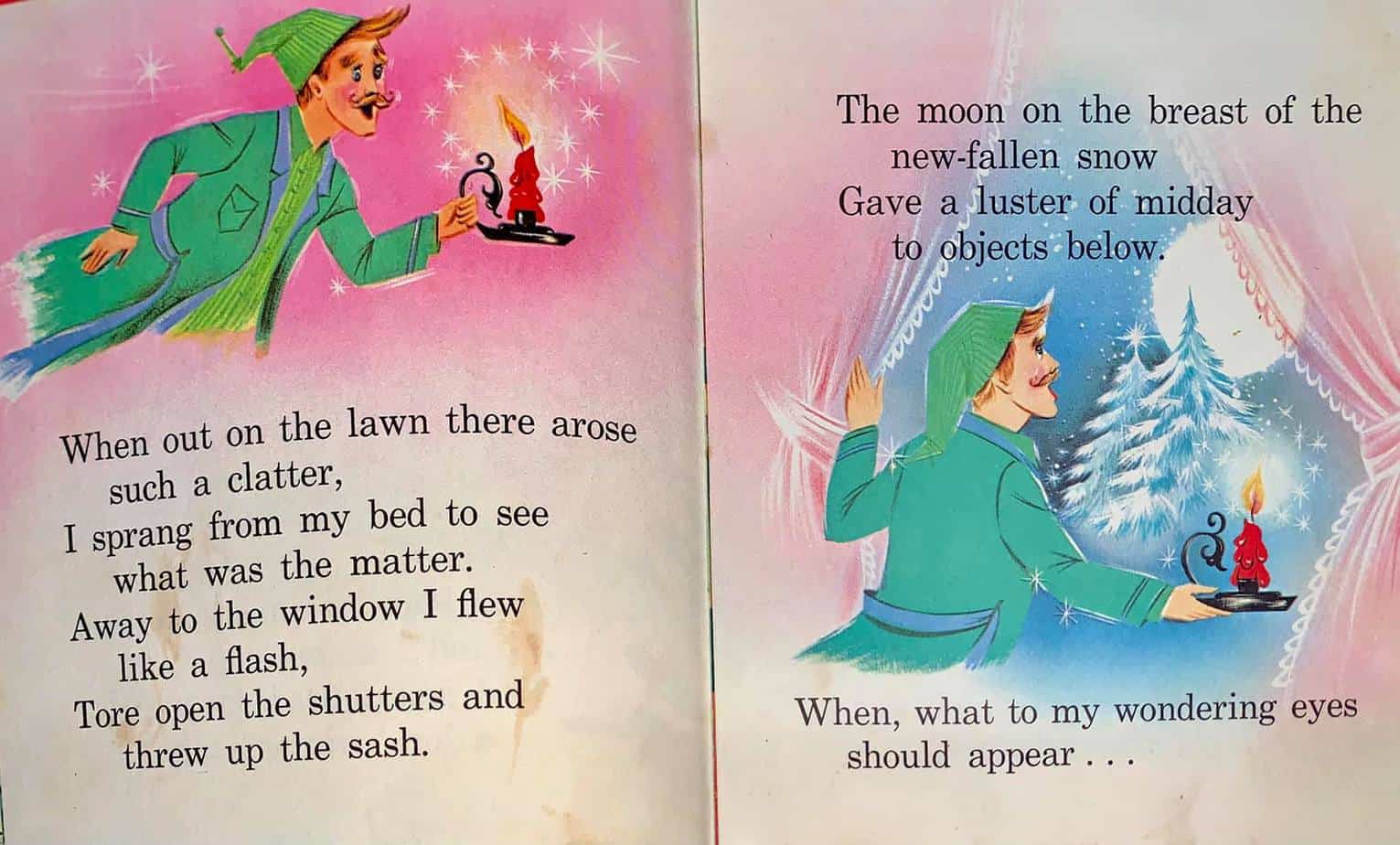

Gyo Fujikawa’s cutaway illustration of a house rendered in soft pastel colours gives us a glimpse of the archetypal picture book dream house.

When out on the lawn there arose such a clatter,

I sprang from the bed to see what was the matter.

Away to the window I flew like a flash,

Tore open the shutters and threw up the sash.

The window is the other main liminal space of a cosy home. The father ‘flew like a flash’ to the window; he is almost imbued with some of the magic of Santa.

The moon on the breast of the new-fallen snow

Gave the lustre of mid-day to objects below,

When, what to my wondering eyes should appear,

But a miniature sleigh, and eight tiny reindeer,

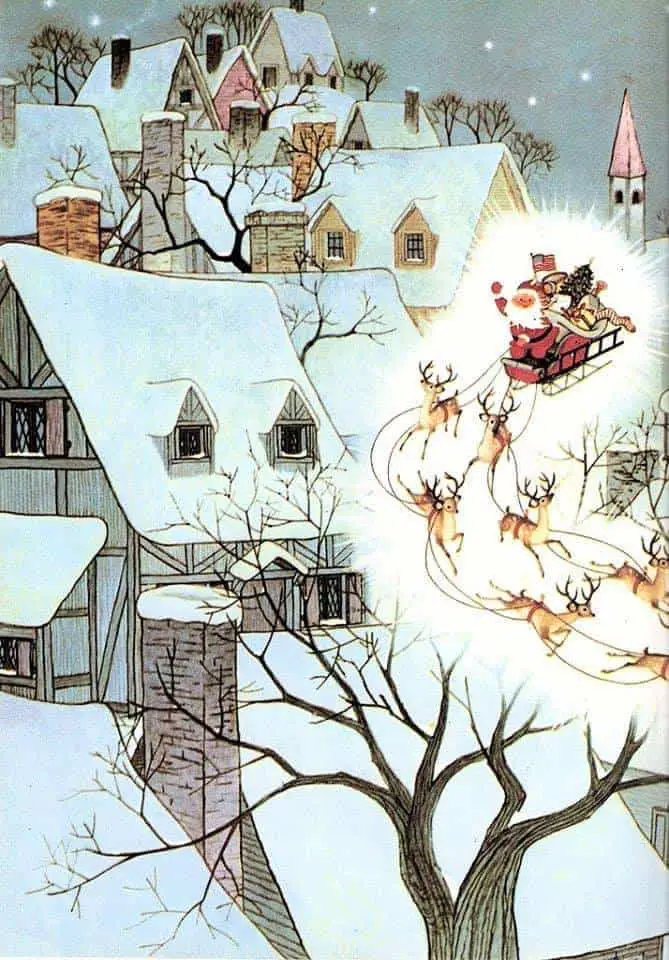

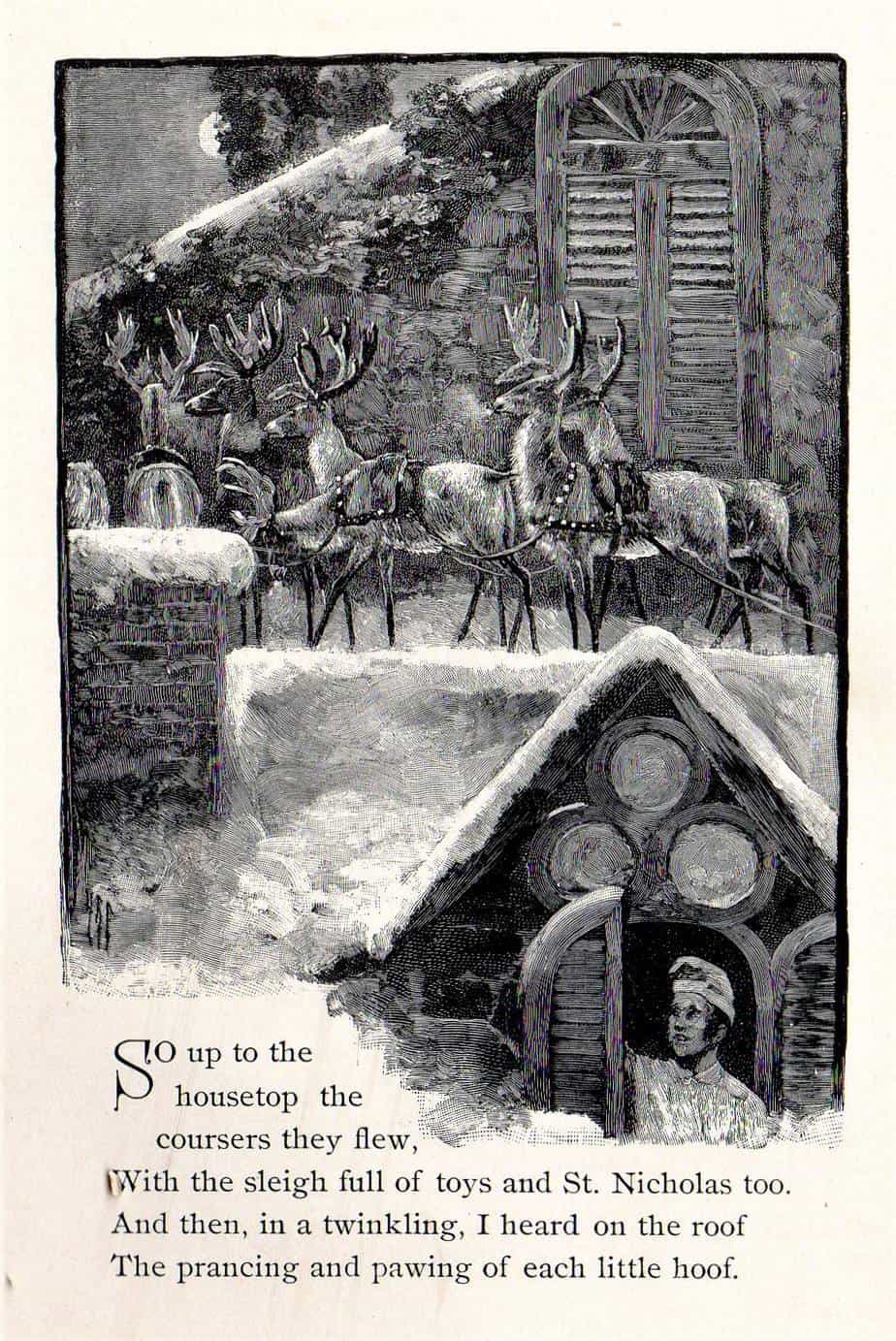

Illustrators vary when deciding the size of Santa and his reindeer. We know that he is ‘tiny’ He must be, right? He needs to fit down a chimney. In some Santa stories, it is assumed Santa is a regular sized guy (if anything on the rotund side) and can shrink temporarily.

With a little old driver, so lively and quick,

I knew in a moment it must be St. Nick.

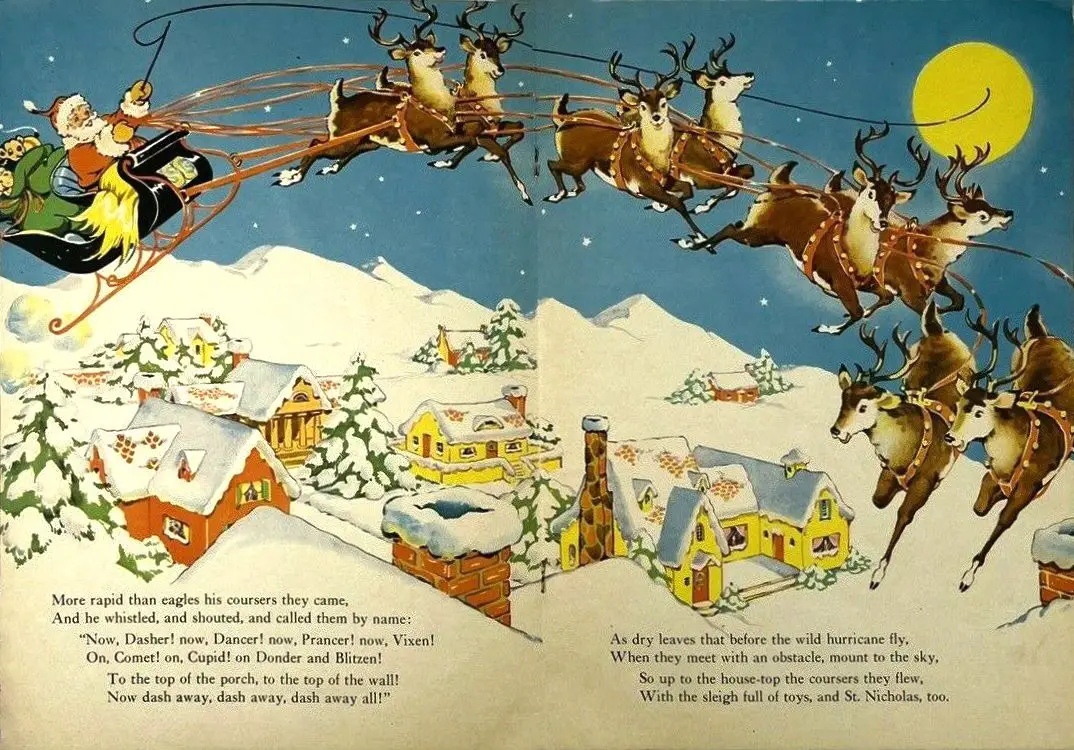

More rapid than eagles his coursers they came,

And he whistled, and shouted, and called them by name;

It’s useful for a poet that Santa goes by a variety of names. ‘Saint Nick’ was a real person,, Saint Nicholas of Myra (270 – 6 December 343) a Christian bishop of Greek descent. He lived during the time of the Roman Empire. He was associated with miracles, and known as Nicholas the Wonderworker. (For the typical story structure of a miracle story, see here.) Saint Nicholas is the patron saint of sailors, merchants, archers, repentant thieves, sex workers, brewers, pawnbrokers, unmarried people, and students in various cities and countries around Europe.

For our purposes, most importantly here, Saint Nicholas of Myra is also the patron saint of children. He was known for his habit of giving out secret, though I guess the origin of those gifts wasn’t so secret after all, since we’re all here now, still talking about him.

“Now, DASHER! now, DANCER! now, PRANCER and VIXEN!

On, COMET! on CUPID! on, DONNER and BLITZEN!

To the top of the porch! to the top of the wall!

Now dash away! dash away! dash away all!”

The reindeer didn’t have names until this poem existed. The ninth, Rudolph, the red-nosed one, was added by Robert L. May in 1939 for a colouring-in book. Rudloph was a hit and soon copyrighted because Rudolph came in handy for an ad campaign.

Frank L. Baum (who wrote The Wonderful Wizard of Oz) tried naming the reindeers himself: Gnossie and Flossie, Racer and Pacer, Reckless and Speckless, Fearless and Peerless, Ready and Steady, but they didn’t stick. I think there should’ve been a Feckless in there somewhere.

As dry leaves that before the wild hurricane fly,

When they meet with an obstacle, mount to the sky,

So up to the house-top the coursers they flew,

With the sleigh full of toys, and St. Nicholas too.

By the way, ‘courser’ is a literary word for a ‘swift horse’ but here it is applied to reindeer.

The first reference to Santa’s sleigh being pulled by a (single) reindeer appears in “Old Santeclaus with Much Delight”, an 1821 illustrated children’s poem published in New York. Obviously, one single reindeer isn’t going to be able to pull Santa and enough toys for the entire world of good children. It was this poem which upped the number to eight.

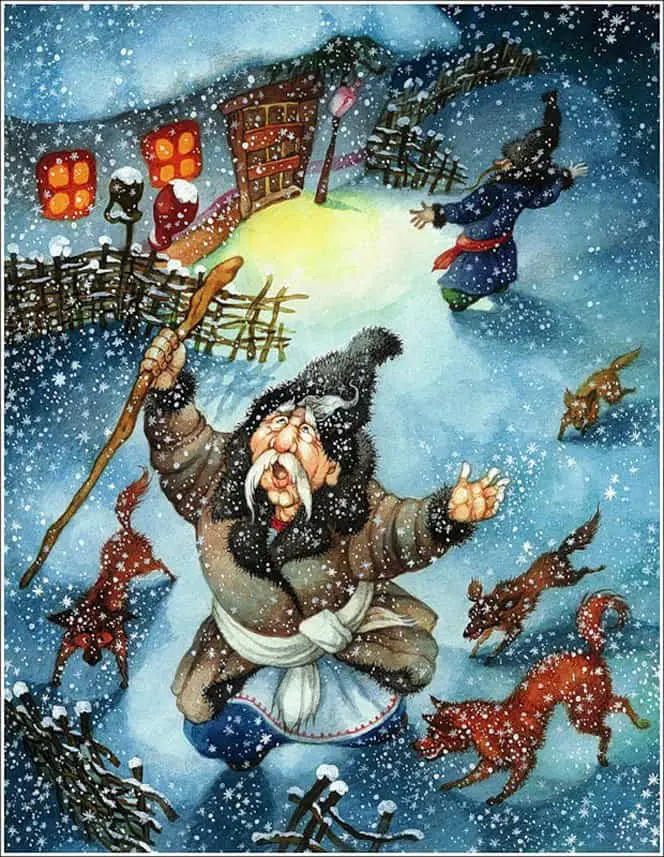

Why reindeer? This harks back to ancient Scandinavian beliefs, and may come from the shamanistic vision of reindeer flying in the sky, which you can see after eating certain muscimol mushrooms. Germans had Odin, a god who rode across the sky on an eight-legged horse. (I’m sure it was actually two horses riding across the sky, if it hadn’t been for the German beer.)

Also, it’s not always reindeer pulling Santa’s sleigh. Beatrix Potter preferred plain old horses.

Here in Australia, there are contemporary Christmas picture books which make use of kangaroos for this sled-pulling purposes.

In any case, humans love the idea of flying animals which are not birds. We love the idea of riding on the backs of animals that fly. It’s everywhere in art.

And then, in a twinkling, I heard on the roof

The prancing and pawing of each little hoof.

As I drew in my hand, and was turning around,

Down the chimney St. Nicholas came with a bound.

Why does Santa come down the chimney? Father Christmas is a sanctified chimney demon. There is a long, long history of superstition in which the chimney of a house serves as a liminal space between safe home and outside dangers of the night. Normally you’d expect nasty creatures such as witches to come down chimneys, all covered in soot and therefore blackened, but Santa never gets his clothes dirty. He doesn’t come to wreak havoc; he brings presents for children. This chimney demon has had his evil powers stripped, replaced with something nice.

He was dressed all in fur, from his head to his foot,

And his clothes were all tarnished with ashes and soot;

A bundle of toys he had flung on his back,

And he looked like a peddler just opening his pack.

Illustrations of Santa tend to leave off the soot.

His eyes — how they twinkled! his dimples how merry!

His cheeks were like roses, his nose like a cherry!

His droll little mouth was drawn up like a bow,

And the beard of his chin was as white as the snow;

Elves are thought to be mischievous (rather than evil), which explains the twinkling in the eye.

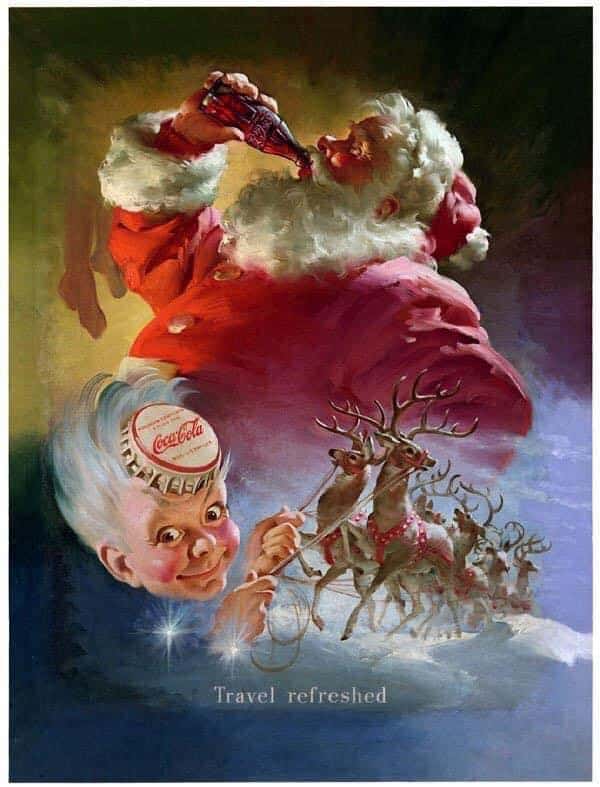

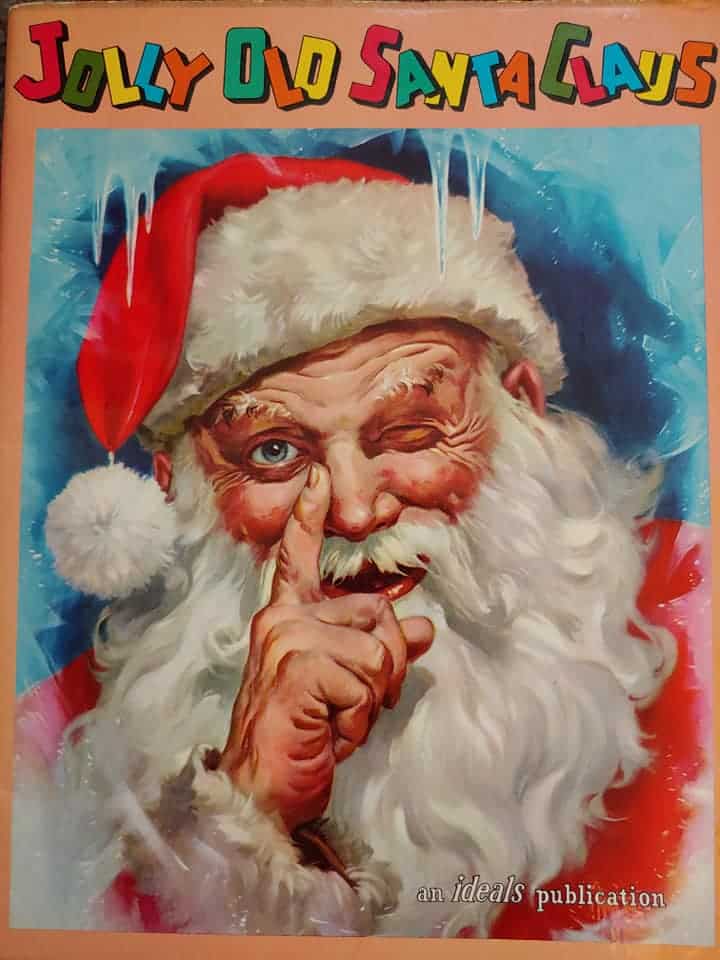

Famously, Santa hasn’t always been red. The Coca-Cola company’s ad campaign with the Santa in the red suit was so successful that this image of Santa has embedded itself in the public imagination, and this includes picture books.

Coca-Cola’s illustrator didn’t come up with the red suit and white trim. The illustrations below show that Santa was dressed in various ways previously, including the red and white variation. The Coca-Cola image made this one stick.

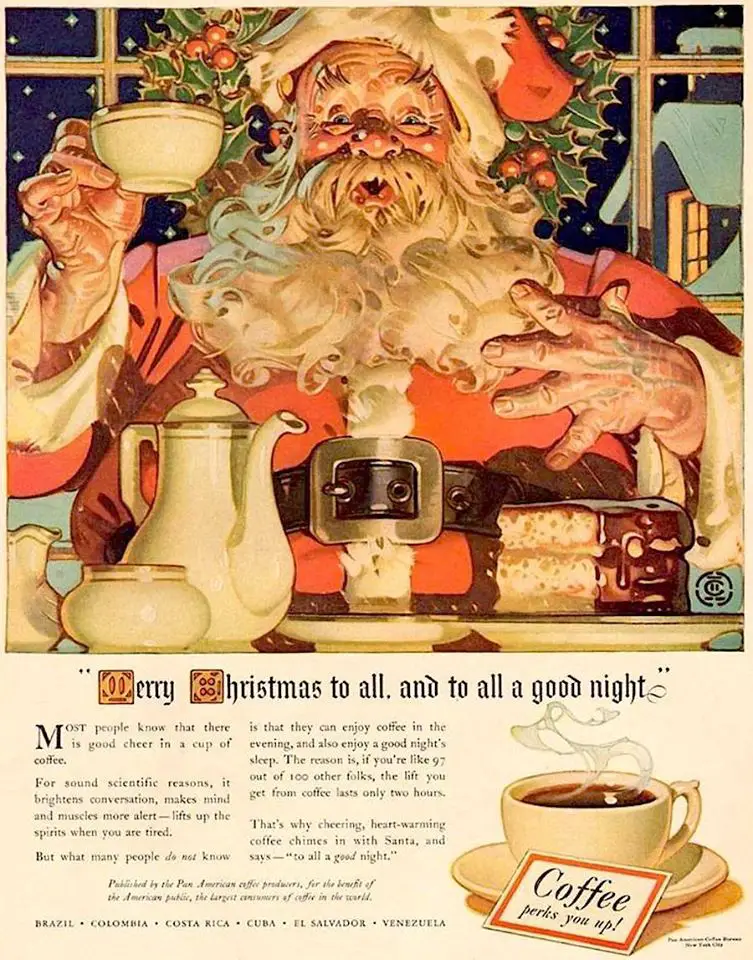

Here’s an advertisement for coffee (no particular company, just a series of ads promoting coffee in general). By now, Santa is firmly in red with white trim.

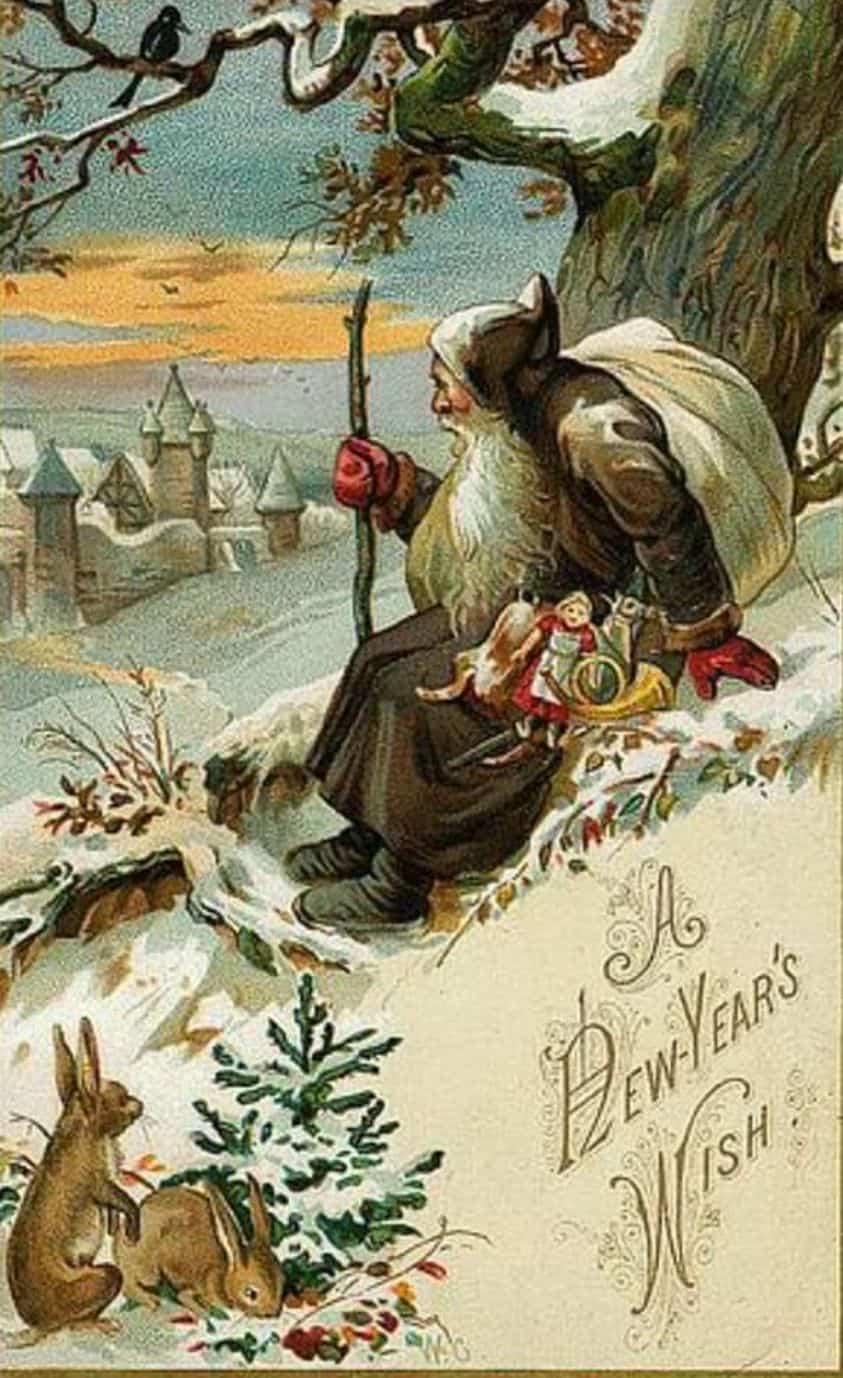

Now and then you still get a non-red Santa. Santa used to be seen more in green.

The stump of a pipe he held tight in his teeth,

And the smoke it encircled his head like a wreath;

He had a broad face and a little round belly,

That shook, when he laughed like a bowlful of jelly.

The pipe is strongly associated with the father of the home.

I deduce Santa’s plumpness is to do with the tradition of leaving goodies out as a welcoming thank you gift for Santa. Santa is obliged to eat all of it. In this particular poem, there have been no treats left out for Santa. It was Thomas Nast’s 1890 image of Santa which solidifed Santa’s image as plump, though this poem paved the way.

He was chubby and plump, a right jolly old elf,

And I laughed when I saw him, in spite of myself;

A wink of his eye and a twist of his head,

Soon gave me to know I had nothing to dread;

Santa sees the father watching him but doesn’t flip out about that. He’s probably used to being watched by curious parents.

In this poem, Santa is described as an ‘elf’, a subcategory of fairy. When I was a kid, I was led to believe that Santa is a magical human surrounded by elves.

However, this idea of Santa, as the head of a toy factory, surrounded by worker elves, is more recent image of cosy capitalism, and helps wealthy Westerners avoid the grim realities of the origin of our consumer goods.

What is an elf, exactly? One, they are small. Two, they are shapeshifters. It makes perfect sense to me now that Santa himself is an elf. He is small, and he can shapeshift himself into the form of a chimney. This is gruesome if you stare at your chimney too long, contemplating a crosscut view.

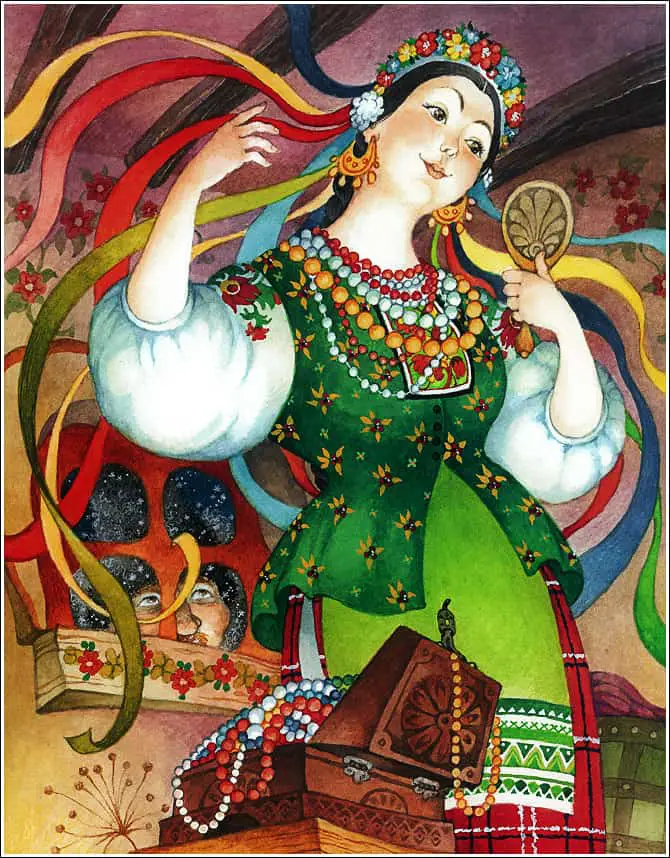

English male elves were thought to look like little old men. But elf maidens were always young and beautiful. A world made entirely of old men and beautiful young women sounds like a supernatural fantasy devised by old men, to me. Modern Santa stories tend to give Santa a same-age wife, often called Mrs Claus.

East West Street” by Phillipe Sands

He spoke not a word, but went straight to his work,

And filled all the stockings; then turned with a jerk,

And laying his finger aside of his nose,

And giving a nod, up the chimney he rose;

A gesture causes magic to happen, a little like the sign Spider-man makes. View Santa from the wrong angle and he will appear to be picking his nose. This imagery became associated with many depictions of Santa in other, subsequent works.

He sprang to his sleigh, to his team gave a whistle,

And away they all flew like the down of a thistle.

But I heard him exclaim, ere he drove out of sight,

HAPPY CHRISTMAS TO ALL, AND TO ALL A GOOD-NIGHT!

Santa wasn’t really even trying to be quiet, was he? With all that clattering on the roof, whistling and now yelling, I deduce he cast some sort of soporific spell over the children to keep them asleep.

STOCKINGS AND HEARTH

Another mandatory decoration in a Christmas picture book: stockings. The chimney may be full of demons, but the hearth is a metonym for familial happiness.

COMPARE AND CONTRAST

The Night Before Halloween (1999) by Natasha Wing and Cynthia Fisher uses the rhyme scheme of The Night Before Christmas but changes-up the holiday, building up to the fun of Halloween Night. Children go trick-or-treating and come face-to-face with a real witch. They run away in delight.

THE NIGHT AFTER CHRISTMAS

This version can be found in The Night Before Christmas And Other Popular Stories For Children.

'Twas the night after Christmas, and all though the house Not a creature was stirring--excepting a mouse. The Stockings were flunt in haste over the chair, For hopes of St. Nicholas were no longer there. The children were restlessly tossing in bed, For the pie and the candy were heavy as lead; While mamma in her kerchief, and I in my gown, Had just made up our minds that we would not lie down, When out on the lawn there arose such a clatter, I spring from my chair to see what was the matter. Away to the window I went with a dash, Flung open the shutter, and threw up the sash. The moon on the breast of the new-fallen snow, Gave the lustre of noon-day to objects below. When what to my long anxious eyes should appear But a horse and a sleigh, both old-fashioned and queer; With a little old driver, so solemn and slow, I knew at a glance it must be Dr Brough. I drew up my head, and was turning around, When upstairs came the Doctor, with scarcely a sound. He wore a thick overcoat, made long ago, And the beard on his chin was white with the snow. He spoke a few words, and went straight to his work; He felt all the pulses, -- then turned with a jerk, And laying his finger aside of his nose, With a nod of his head to the chimney he goes:-- "A spoonful of oil, ma'am, if you have it handy, No nuts and no raisins, no pies and no candy. These tender young stomachs cannot well digest All the sweets that they get; toys and books are the best. But I know my advice will not find many friends, For the custom of Christmas the other way tends. The fathers and mothers and Santa Clause too, Are exceedingly blind, Well, a good-night to you!" And I heard him exclaim, as he drove out of sight: These feastings and candies make Doctors' bills right!"