Today’s film makes a lot more sense when you sit back and accept it’s not supposed to make sense at a surface level. However, it does sense if you read the story at a metaphorical level.

I’m about to present you with theories.

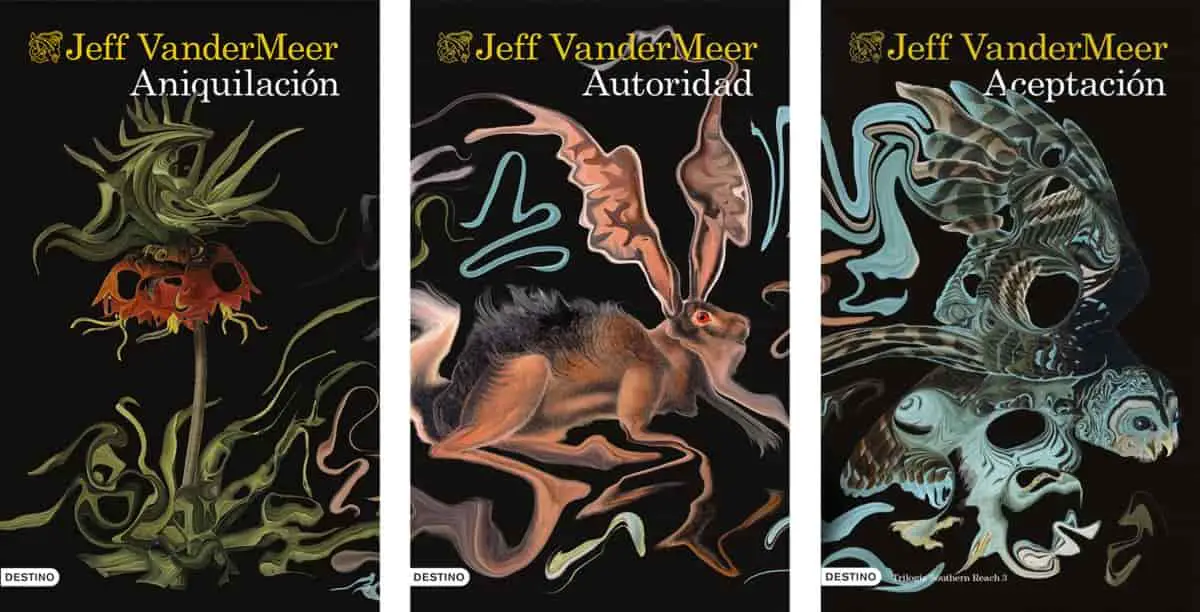

Annihilation is a 2018 film based on a novel by Jeff VanderMeer. Annihilation is the first of a trilogy. Each title begins with the letter A: Annihilation, Authority, Acceptance. ‘Southern Reach’ is the name of the secret authority which arranges missions into Area X, where strange things happen.

The film is directed by Alex Garland, who also wrote the screenplay, and who years ago wrote The Beach.

Viewers who’d read the book were surprised to learn there would be a film adaptation, because Annihilation, the book, is widely thought to be ‘unfilmable’. Nope. Got filmed. Was the film a success? Well, not at the box office. Is it a cult favourite? Perhaps.

Whether you feel Annihilation is a successful adaptation or not, this film contains a stand-out, resonant horror scene: The bear, who screams “Help mee!”

PARATEXT OF ANNIHILATION

A biologist signs up for a dangerous, secret expedition into a mysterious zone where the laws of nature don’t apply.

logline

This is basically a Final Girl story and we know this from the start. Each member of an expedition will be picked off one by one, except for Lena who makes it out alive, though traumatised and strangely changed.

ANNIHILATION AS COSMIC HORROR

Annihilation has been called a modern example of cosmic horror. In common with vintage cosmic horror, no one knows what the heck is going on in this world. There’s just some low moaning in the night and bizarre things happen, all to remind us that we’ll never understand the mysteries of the universe. (The point of cosmic horror.)

IS ANNIHILATION DIFFICULT TO FOLLOW?

This story is designed to work mostly at a metaphorical level. Watching Annihilation requires its audience to sink into a reverie. Like any highly symbolic form of storytelling, there will be as many interpretations as there are audience members.

The first book focuses on the biologist and the psychologist. Readers never learn much about the other characters, at least not in the first book of the trilogy. (So if you’re hoping the book will give you more answers, well, maybe if you read all three, I dunno.)

ANNIHILATION AS UNEXPECTED PAGE-TURNER

Despite the lack of discernible plot, a large number of consumer reviewers have said that Annihilation is a page-turner. But is it a page-turner in the traditional sense? Readers turn the pages of this book in the hope that all is about to become clear. (In a traditional page-turner, readers understand what’s going on. They turn pages because they want answers to clearly defined mysteries which will eventually be explained.)

ANNIHILATION AS EXCELLENT EXAMPLE OF MYTHIC STRUCTURE-COMBO

I’m about to make a weird comparison. Hear me out.

I think Annihilation has something big in common with The Wind In The Willows.

I mean structurally. The Wind In The Willows is a stand-out example of utopian fiction and Annihilation is, well, not that. But both stories are an uncommon combination of all three main types of mythic structure.

Different people use different names to describe the three different types. I like Odyssean, Robinsonnade and Interoceptive. Interoceptive myths have also been called ‘The Female Myth’ and are very new compared to the other two ways of structuring a story.

Back in 1983, writing about children’s literature, scholar Lucy Waddey used the following terminology:

- The Odyssean pattern: Home is an anchor and a refuge, a place to return to after trials and adventures in the wild world. Home corresponds to Arcadia. This is the ‘here and back again’ pattern in both The Wind in the Willows and in Annihilation.

- The Oedipal pattern (Also called the Robinsonnade mythic structure.): Found in domestic stories (Little Women, Little House etc.) These are stories where the child stays marooned in the home, but perhaps leaves imaginatively. This Oedipal pattern is also used in adult fiction when writing about women who, like children, are often confined to the home and can only escape in their imaginations. Annihilation is a rare example of an action adventure story with more women than men. There’s a historical, storytelling reason for that. Although there’s no literal ‘island’ in Annihilation, when the women enter The Shimmer, they are effectively marooned.

- The Promethean pattern: In these stories there is no home at the beginning of the story but the main character creates one as part of their maturation (The Secret Garden is a children’s book example of that). When the main character of Annihilation enters that lighthouse, the story is doing something different from your usual run-of-the-mill film. Did it feel a little weird to you? Like, what’s happening here? And why? That’s because, normally, when characters go on some big journey, narrowly avoid death after their comrades are picked off, then gaze out onto the ocean, that marks a self-revelation and the end of the story. But Lena Double (symbolic name, much?) finds a ‘new home’ by going deep inside herself, literally confronting a sci-fi, shiny embodiment of her darkest desires.

Why do I use the word ‘Interoceptive Mythic Form’? Because I don’t like to perpetuate the notion that it’s girly to go deep inside yourself and examine your own emotions, oftentimes avoiding physical tousles, using your brains to overcome adversity. (Moreover, so-called ‘Female Myths’ don’t always star girls and women. Equal opportunity brain power!)

The Interoceptive “Female” Myth is much newer (1970s onwards) and the usual audiences are taking a while to warm to it.

Due to a poorly received test screening, David Ellison, a financier at Paramount, became concerned that [Annihilation] was “too intellectual” and “too complicated,” and demanded changes to make it appeal to a wider audience, including making Natalie Portman’s character more sympathetic and changing the ending. Producer Scott Rudin sided with Garland in his desire to not alter the film, defending the film and refusing to take notes. Rudin had final cut.

IMDb

Taglines on the Annihilation posters let us know that the main character will be going inside herself, and that the outer storyworld is a physical manifestation of her own turmoil. There’s nothing particularly new about that, of course:

One way in. No way out.

Fear what’s inside.

taglines

Originality is all in the execution.

Now to a different children’s book comparison. (Though honestly, I don’t think The Wind In The Willows is a children’s book.) The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. Annihilation is likewise one of those stories which is so metaphorical, interpretation is wholly contingent upon what the audience brings to it.

I’m also reminded of Watership Down by Richard Adams. Rabbits are forced from their home due to environmental destruction. They don’t know what’s going on. The difference in that story: The human audience does understand that the threat is humans. There’s an ironic gap there between the rabbits and the audience. Watership Down works differently for children, who are as naïve as the rabbits.

To watch Annihilation is to be a child once again: Something is happening, something we don’t understand. We have nothing to do but identify with the characters as they navigate the story as it plays out.

VARIOUS MEANINGS BEHIND THE STORY OF ANNIHILATION

There is an aspect of Annihilation which may speak especially to anyone who can become pregnant. Annihilation is an allegory for cancer, which can affect anyone, but I’d like to talk about The Fear of Engulfment.

The Fear of Engulfment is very specific and affects mainly women. The movie taglines absolutely apply to that feeling of being impregnated without consent, then forced to go through with it. Fairytales have been dealing with this topic for millennia. (Check out The Frog Princess.) Childbirth is much safer these days, but imagine being pregnant just 100 years ago, before antibiotics. Imagine being pregnant before Caesarean section. Imagine being pregnant because someone made you so, without your consent.

Many people living today, mainly women, don’t have to imagine this. And even with the best healthcare privilege can buy, the threat of having your body inhabited against your will is ever-present for many women, requiring constant vigilance. Annihilation can be seen as an allegory for that, working subtly at a metaphorical level.

As well as the cell division we’ve got:

- The bodies of water

- The roundness of the bubble

- The reality of being alone in this (Double’s husband disappears)

- A medical setting

- Surrounded by women (metaphorical doulas, midwives)

- Double has lost a child

- The reality that it’s impossible to fight the ‘opponent’ of childbirth; all you can do is coax a child out, as Lena Double does to the alien at the end (when she persuades it to destroy her own mimic).

SETTING OF ANNIHILATION

The author has said that Area X is to human beings as human beings are to the rest of the animal kingdom: a force that colonises the world. The other animals don’t understand it, but are forced to live with us and our strange technology anyhow. (Hence the Watership Down similarities.)

PERIOD

We never know. The wrapper story seems set in an alternative present or near future.

DURATION

We never know. This story does not work in the realm of chronos, but instead takes the audience into mythos, fairytale time. This must be more akin to how animals experience time, since chronological time is a human construct.

Messing with our sense of time is one way to deliberately disorient the audience. However, I don’t think this disorientation works particularly well in a film format. The audience is at all times aware of how much movie runtime is left. I didn’t personally feel disoriented regards time in a way better achieved by the written word.

LOCATION

Annihilation attempts to mess with our sense of time and it is also constantly messing with our sense of borders. It even wants to mess with the border we have between ourselves and the rest of the world we’re a part of. The environmental messaging is clear: We are at the mercy of our environment because we are literally a part of it.

Area X is an uninhabited and abandoned coastal area of an unnamed country which feels like America to me. Nature is gradually reclaiming the territory.

ARENA

Area X exists inside a dome/bubble known as The Shimmer.

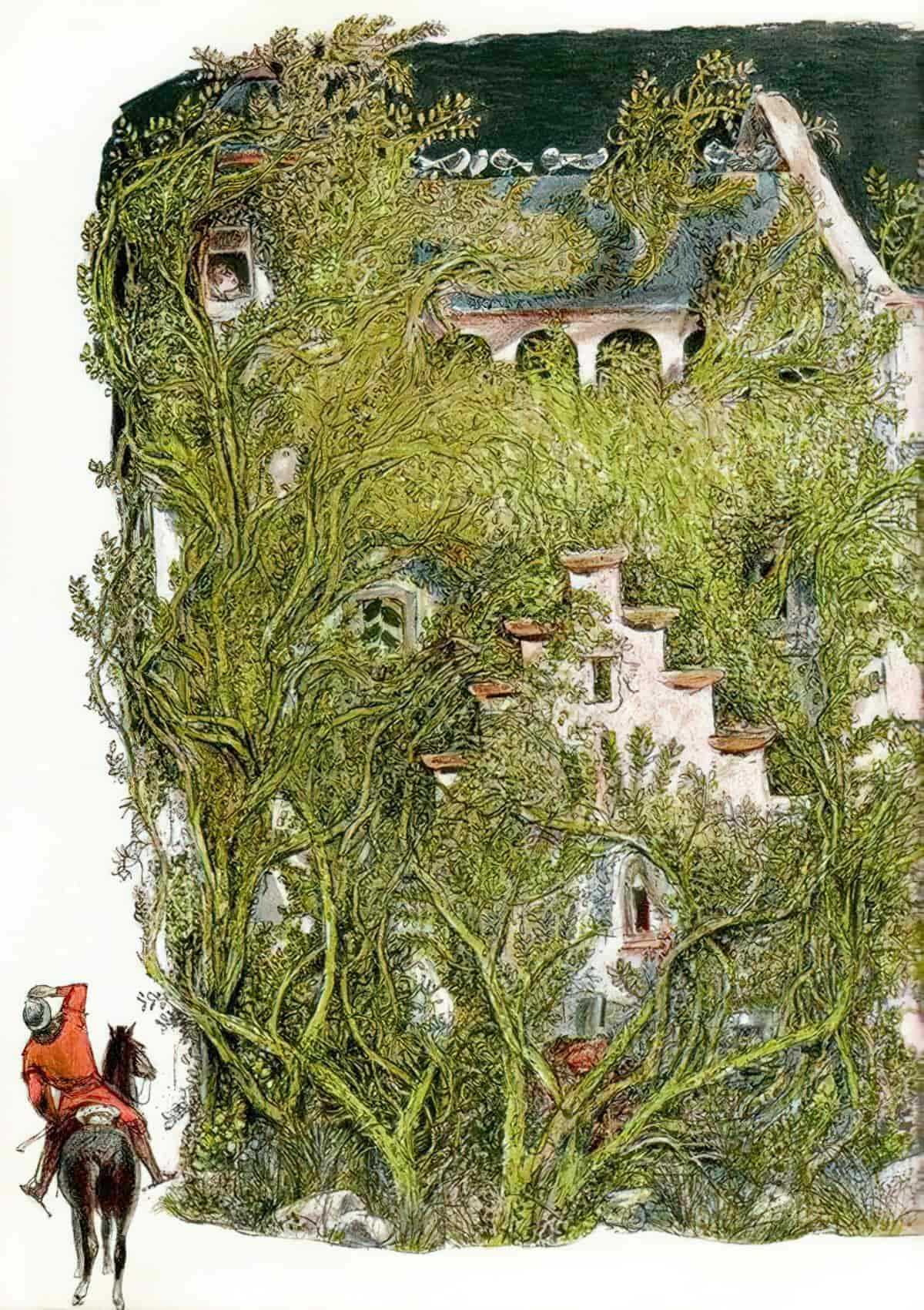

The artwork below stands out to me as another example of a bubble/cryptobotany combo. The bubble or domed world carries the symbolism of islands, cut off from the outside world, harbouring mysteries.

MANMADE SPACES

Inside The Shimmer, farmland with farm buildings show signs of former rural life. They seem to have been abandoned years earlier.

NATURAL SETTINGS

Because of the abandoned house vibe, there’s no delineation between man-made and natural spheres. Anything man-made will eventually be reclaimed.

The author was inspired to create Area X after a hike through St. Marks National Wildlife Refuge, South of Tallahassee, which must have been a pretty wild experience. Remind me never to go there. (All the kooky things happen in Florida.)

The Shimmer covers a number of natural settings, but significantly, these natural settings intermingle with manmade equivalents.

- The abandoned swimming pool, which mirrors a natural lake.

- The scientists keep watch from a tower, which stands in for a mountain-top.

All of this culminates in the uber-intermingling of human and nature: Foliage which grows according to human DNA, using our Hox genes.

WEATHER

A temperate, jungle climate (inspired by Florida). In many stories, the jungle is utilised as a metaphor for the city. We see this across many genres, especially noir, action, thriller and even in children’s picture books. Here, jungle is the symbolic equivalent of civilisation (reclaimed).

TECHNOLOGY CRUCIAL TO THIS PARTICULAR STORY

The ‘technology’ comes from evolution, outside human control.

You can’t crossbreed between different species.

Lena (and yet we see just that). In mythic stories you can, cf. the many chimerae found in world mythology.

A human/plant combo has a surreal quality to it, but I’d like to focus attention on the ‘true’ meaning of Surreal, which doesn’t mean ‘uninterpretable’ but instead means the opposite: Super-real. The Surreal imagery of Annihilation is saying something super real (deep) about human kind: We are not in control. We’ve told ourselves a story that we dominate the planet, but we are temporary blips in Earth’s history. Evolution is not under our own control because we, ourselves, are its products.

THE TOWER TUNNEL

At the start of the book, the expedition are about to enter an underground tunnel, but the biologist refers to this tunnel as a tower. The Tower Tunnel. Now, readers all understand that towers stretch up, whereas tunnels burrow under. These two things are altitudinous opposites of each other. How can something be both a tower and a tunnel at once? Well, in this story, it can. Nothing is fixed; space and time work differently. The biologist herself can’t understand how she can know this structure to be a tunnel, yet in her mind she knows it to be a tower.

At first, only I saw it as a tower. I don’t know why the word tower came to me, given that it tunneled into the ground. I could as easily have considered it a bunker or a submerged building. Yet as soon as I saw the staircase, I remembered the lighthouse on the coast and had a sudden vision of the last expedition drifting off, one by one, and sometime thereafter the ground shifting in a uniform and preplanned way to leave the lighthouse standing where it had always been but depositing this underground part of it inland. I saw this in vast and intricate detail as we all stood there, and, looking back, I mark it as the first irrational thought I had once we had reached our destination.

Annihilation, Chapter One

In this way, the setting is dreamy. Like, you’re in this dream place you’ve literally never been to before, yet somehow you know in the dream that this is your school. It’s totally not your school. It doesn’t look one bit like your school. Yet in your mind, you know it to be school. Jung the psychoanalyst had big fun with this — dreams, symbols and so on.

Basically, perception is subjective in this (dream)world of Area X. And the biologist soon learns that there’s no real distinction between alive and not-alive, either. The Tower Tunnel is a living, breathing beast, with breathing lungs and a heartbeat. They all seem to be inside its stomach, somehow.

The connection between an upward structure vs a downward structure isn’t original to VanderMeer. We see it in the ancient symbolism of fairytale, another highly symbolic form of storytelling with much in common with dreams. In fairy tales, the tower is similar to the water well.

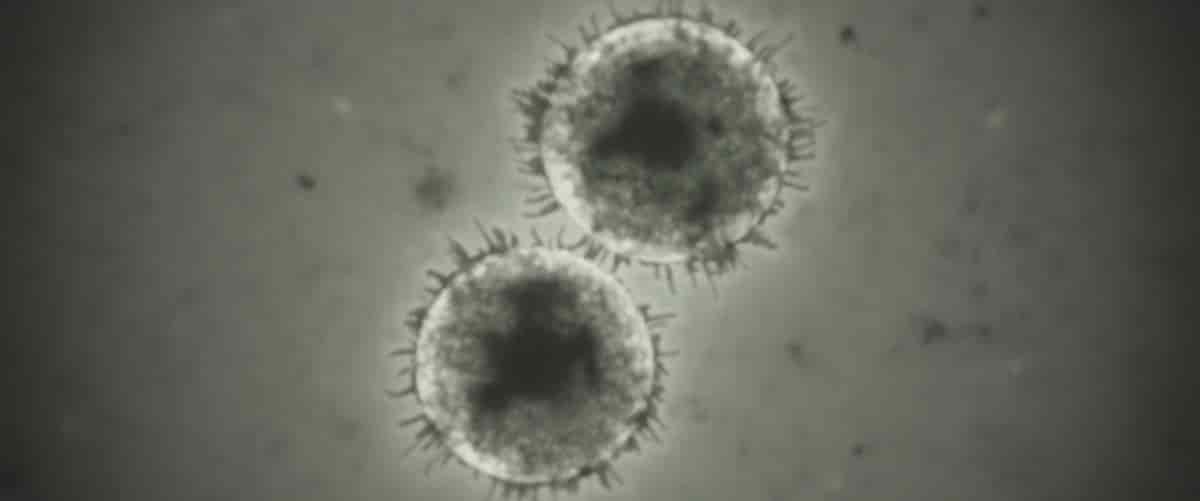

Now to the inherently feminine sensibility of this story: Both the tower and the well are round structures associated with women and girls on the cusp of marriage, pregnancy and childbirth. When Lena tests her own blood and observes it she is confronted by what she sees going on inside her. There’s life inside her, doing its own thing.

In the terminology of Vladimir Propp, towers are frequently used in fairytale in place of an interdiction (warning). Makes sense. If you lock your daughter in a tower, you don’t really need to give her warnings; it’s not like you expect her to go anywhere.

LEVEL OF CONFLICT

Others have pointed out how this story mirrors the Five Stages of Grief and is analogy for cancer at a global scale.

I’d like to expand the metaphor beyond the division of cells. This story continues the theme in the subplot of a marriage, as a couple works out between them where self ends and partner begins. The same issue needs to be worked out for mothers (and their children) after childbirth, as the slow bifurcation between selfhoods begins. “You came from me, you can kill me, but you are not me. I reject you as me.” In this way, babies are like cancer.

STORY STRUCTURE OF ANNIHILATION

INCITING INCIDENT

Inciting incidents can be tricky to pinpoint, but the job is easier once realising stories contain multiple inciting incidents. Namely: The external one (in which the story world changes) and the internal one (in which the main character makes a decision to act).

In Annihilation, an external inciting incident happened three years earlier: Something crashed into a lighthouse.

SHORTCOMING

Lena the biologist is grieving. She has lost her husband (in mind if not in body). She is also at a massive disadvantage because she’s been thrown into an environment where information is withheld. It’s her job to solve a mystery, but she hasn’t been given the question. Lena is of course the viewpoint character for the audience. Writers make her smarter (more educated) than us so we don’t get too frustrated.

DESIRE

In the book, none of the women get names. Basically, the main characters are defined by their occupations and roles. They’ve been charged with the task of journaling their time in Area X. They’re not allowed watches or compasses, and don’t know how long they’ll be there, or what they’re there to do.

Writers will recognise immediately, this goes against generic storytelling advice to give your characters a desire and a plan. The author’s job thereby became many times more difficult, because narrative drive without desire and a series of changed plans (as things go wrong) is very difficult to accomplish. (In fact, you won’t achieve the narrative drive audiences have become used to. You’re now creating a story for people with a tolerance for weird fiction and mystery boxing.) This explains why the book is relatively short. Readers have a limited tolerance for stories whose plots never truly reveal themselves.

OPPONENT

The psychologist should by rights be an ally, but because she has cancer herself and is on a suicide mission, she is a robotic, unfeeling false ally opponent who would rather have answers than life.

Along the way, the women meet various terrifying opponents.

PLAN

Push on, observe, don’t get killed. As in a dream, terrors appear, they deal with them as the occur, but are sometimes frozen by fear, or overawed or somehow spaced out.

Not clear in the book: The reason why the scientists keep pushing forward. This is partly to do with the journalistic narration. We’re told what they see, but their reactions to very bizarre stuff is strangely muted because they are there to do a job. But also, this lack of reason for pushing forward contributes to the dreamlike atmosphere. In a dream we often don’t know why we’re in a place. We only know we’re there, aware of the sensory information in the moment. The reading and viewing experience emulates the experience of dream. Don’t engage the analytical part of your brain; we’re not meant to. Read the symbolic layer instead. That’s what I’ll be doing today.

THE BIG STRUGGLE

Clear in the book but not so clear in the film: the hypnotising spores which affect the psychologist. Something is reaching into the scientists and extracting things. (Cf. the Fear of Engulfment theory.)

ANAGNORISIS

“Annihilation” functions like a magic word which leads to annihilation. Once you say it, it’s an illocutionary act.

In common with a typical lyrical short story, the revelatory section of this film is lengthy, and it’s not entirely clear what the biologist has realised, exactly.

NEW SITUATION

This motif of light is never explained but Lena’s husband uses the brightest light (phosphorous) to kill himself. The light is deadly; knowledge is light; knowledge can kill you here, or at least the pursuit of it.

Note that the light at the end of the tunnel shifts from the viewer looking down the shaft towards Lena to us looking up the shaft, alongside Lena. We, the audience, merge into Lena.

Light as revelation is hardly unique to this story. The difference is, we are never told what shape that revelation should take. The cinematography takes us on a sensory, disorienting trip which will either satisfy or frustrate, depending on viewer expectations.

Farewells can be shattering, but returns are surely worse. Solid flesh can never live up to the bright shadow cast by its absence.

Margaret Atwood

EXTRAPOLATED ENDING

If the ending of Annihilation feels… odd, it’s not just the stuff that happens inside the lighthouse. It’s because we weren’t expecting that last bit. Fortunately, ‘oddness’ also equals ‘original’ and ‘thought-provoking’.

Helplessly Hoping by Bing, Stills % Crosby formed the soundtrack to the film adaptation of this story.

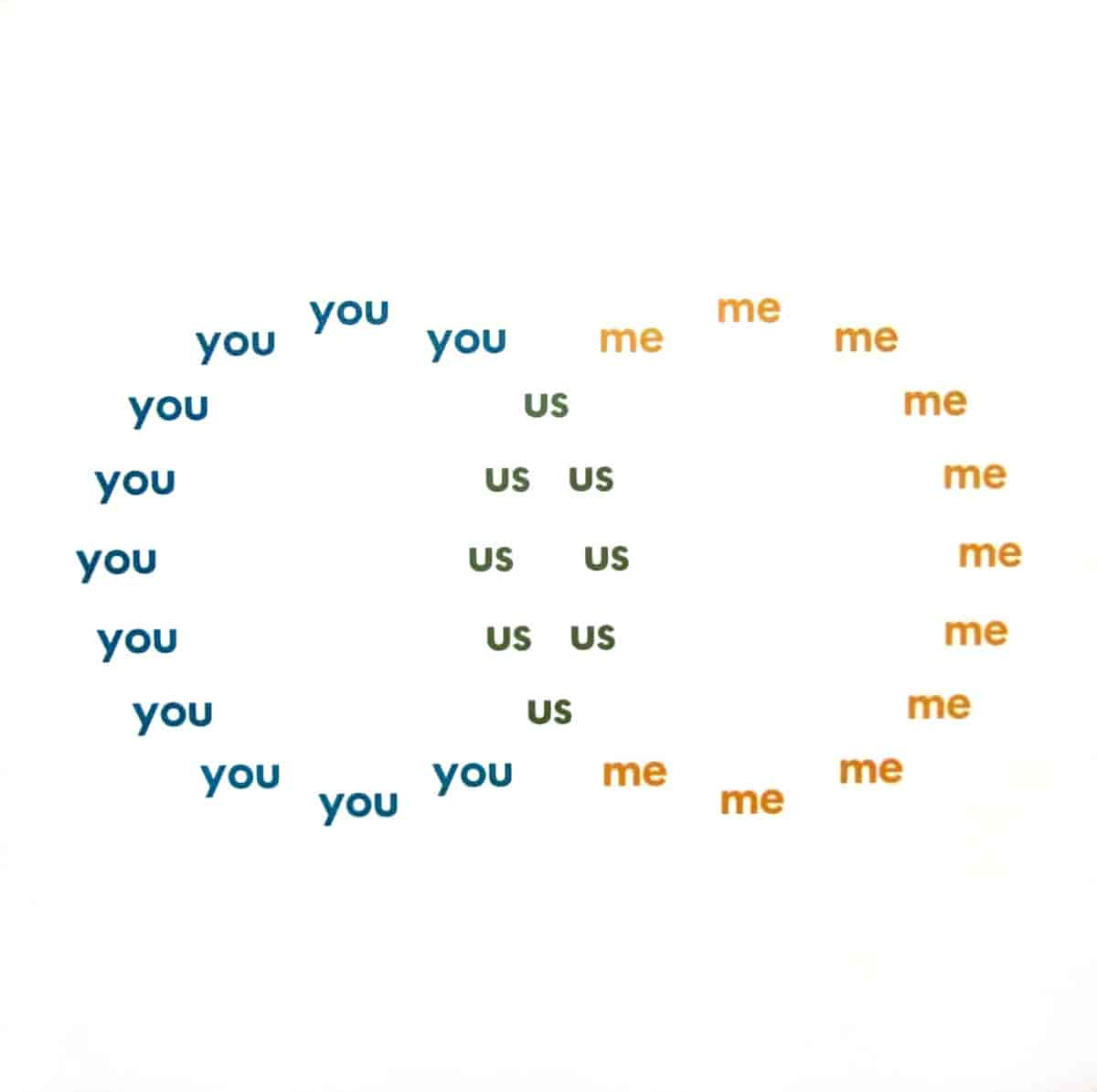

They are one person They are two alone They are three together

These three lines from it seem especially fitting. The mathematics don’t add up. Even something which seems as universal as arithmetic may in fact be far more complicated than humans know. (What astrophysicists suspect about quantum theory certainly points towards some unimaginable weirdness, forever just out of our grasp.)

Let’s talk about the romantic subplot. What might this story say about human relationships?

Lena: Are you Kane?

Silence

Kane: I don’t know.

Beat.

Kane: Are you Lena?

We are all constantly changing, down to our very cells. But when we commit to a partner, we are choosing that person at a specific point in time. We can only hope that we change in tandem, because stasis is impossible. This realisation is terrifying.

RESONANCE

Humans have long considered what might happen if trees came alive. Tales of Baba Yaga and her house with chicken feet were probably inspired by the part of a tree where the roots meet the earth.

FOR FURTHER INVESTIGATION

Cara chats with Dr. Kelly Weinersmith, co-author of “Soonish: Ten Emerging Technologies That’ll Improve and/or Ruin Everything.” They talk about her work as a biologist and ecologist, focusing on parasitic agents that manipulate host behavior. Then the conversation shifts to her new book (co-written with her husband, Saturday Morning Breakfast Cereal comic creator Zach Weinersmith).

BRAIN DAMAGE (1988) takes its title quite literally, as an intoxicating parasite devours brains to keep its host in a hallucinatory state. Jason Baxter revels in Frank Henenlotter’s garishly neon 1988 video aisle classic, exploring the not-so-hidden meanings beneath its slimy surface. (Review at Bright Wall/Dark Room)

Lethal vegetation has long been a metaphor for female disobedience, in Western mythology and in society at large. This concept has developed over time across two main trajectories. In the first, dangerous botany embodies patriarchal anxieties over female access to education and wisdom. The tale of original sin, for example, implicitly cautions against curiosity in women: Eve’s act of eating a fruit from the tree of knowledge sets the stage for all evil on Earth. In Greek mythology, the goddess Hecate was seen as a morally ambivalent figure because she protected families from harm, but was also associated with poisonous herbs administered in witchcraft. Such stories offer an allegorical warning that women can’t be trusted with knowledge, lest they use it to bring disorder to mankind.

Why Pop Culture Links Women and Killer Plants: Botany is seeing a mini-revival as a plot device, adding a transgressive edge to recent films like Phantom Thread and Annihilation. By Amandas Ong, The Atlantic