Andrew Henry’s Meadow is a 1965 picture book written and illustrated by Doris (“Doe”) Burn (1923 – 2011), an American storyteller who illustrated her picture books in a small Waldron Island cabin with no facilities.

Australian comedian Celia Pacquola does a bit where she explains how her father was a builder, and as a kid, she had the most awesome play house in the back yard. This was no ordinary ‘play house’. He’d built her an actual, proper miniature house. That’s the set up. The punchline is that her father built her a house so she’d move out. She concludes the gag by explaining that her dad wasn’t much of a father, but made an excellent neighbour.

Scientist and science communicator Michio Kaku also has a story in which he built a 2.3 eV “atom smasher” in his garage for a high school science fair. For this he used scrap metal and 22 miles of wire. He created a magnetic field 20,000 times stronger than Earth’s. He was lucky not to kill himself. Kaku’s mother took this in her stride.

The main character of this picture book has a story somewhere between Pacquola’s and Kaku’s. He likes to invent contraptions in his family home, which annoys the heck out of everyone. So he moves out. Builds his own damn house.

THE DEVELOPMENTAL BENEFITS OF BUILDING FORTS

Forts have always been a part of childhood, says David Sobel, professor emeritus at Antioch University’s education department and author of “Children’s Special Places: Exploring the Role of Forts, Dens, and Bush Houses in Middle Childhood.” Sobel researched the developmental function forts play in children’s lives across cultures. They are universal, he says, driven by “biological genetic disposition” as children develop a “sense of self,” separate from parents.

Why kids love building forts — and why experts say they might need them more than ever, Washington Post

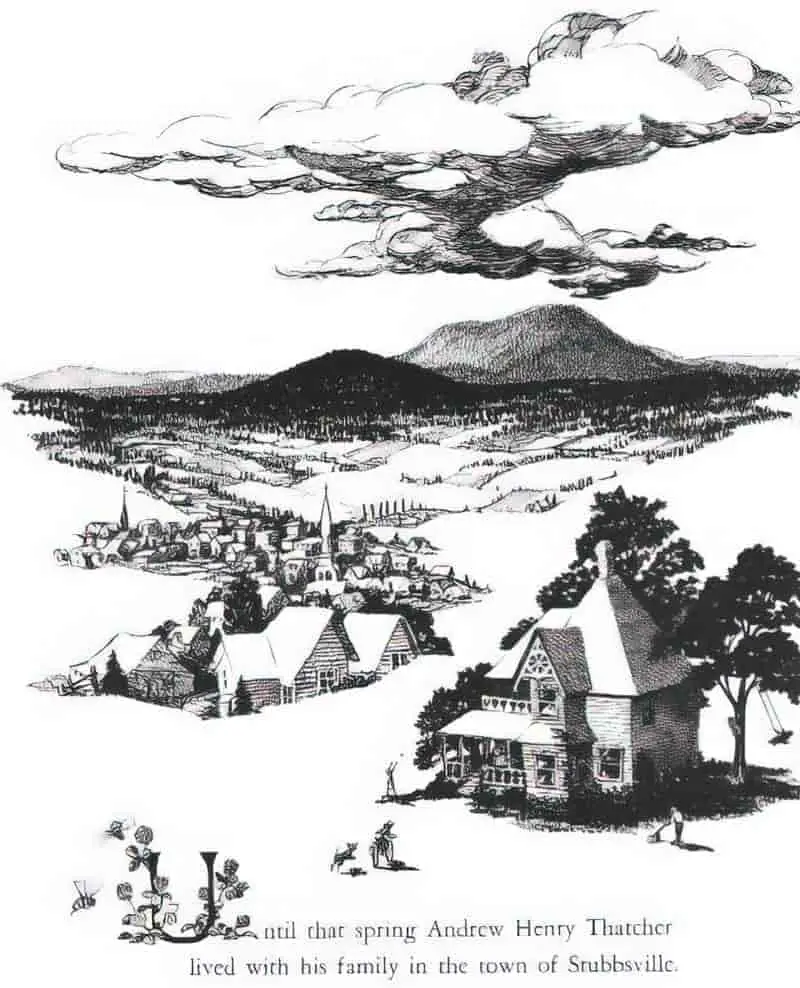

The story begins:

Until that spring, Andrew Henry Thatcher lived with his family in the town of Stubbsville.

Andrew Henry’s Meadow

Older picture books especially tend to have a lengthy set up, meaning readers are told all about the main character’s family, what they do each morning and so on and so forth. Then the real story begins, the shift marked by a phrase such as ‘Then one day…’ (This switch has been called the shift between iterative and singulative time. Contemporary picture books tend to have a shorter iterative section.)

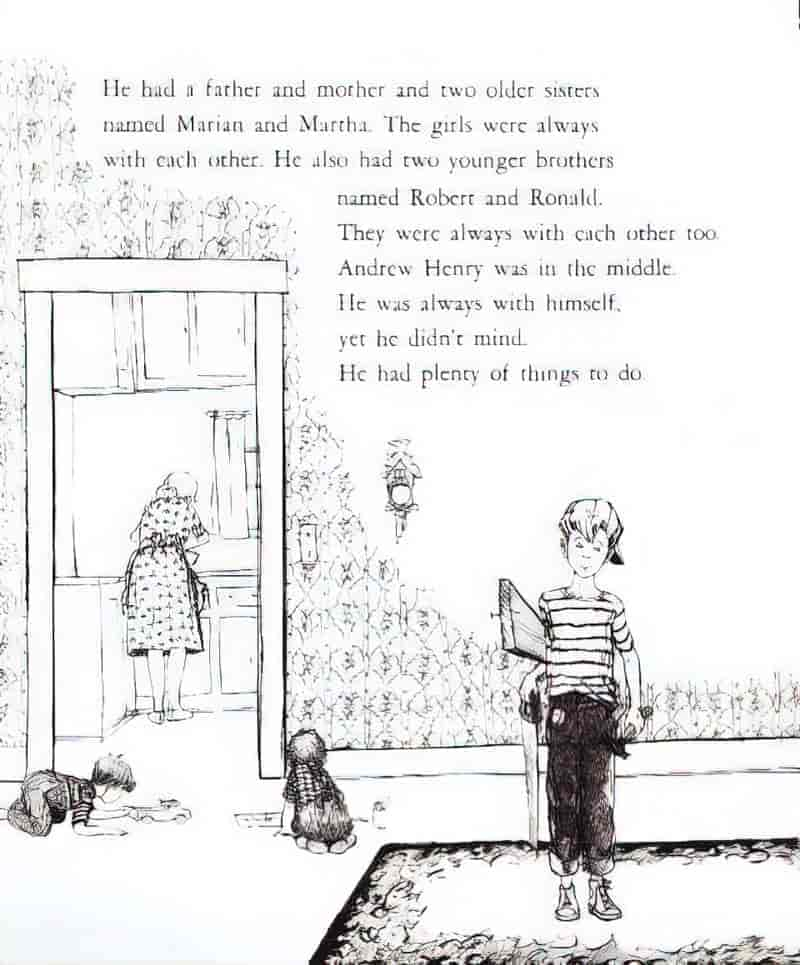

This retro children’s book by Doris Burn is of its time; it is much longer than most contemporary picture books, and we’re about to learn all about how Andrew Henry is the middle child, how he is alienated from his siblings and parents, and how his contraptions annoy everyone.

Of interest to storytelling: the first three words of the story: ‘Until that spring’. Right away, readers understand that something big happens in spring. These three measly words increase the tension and get us through the rather lengthy introductory period.

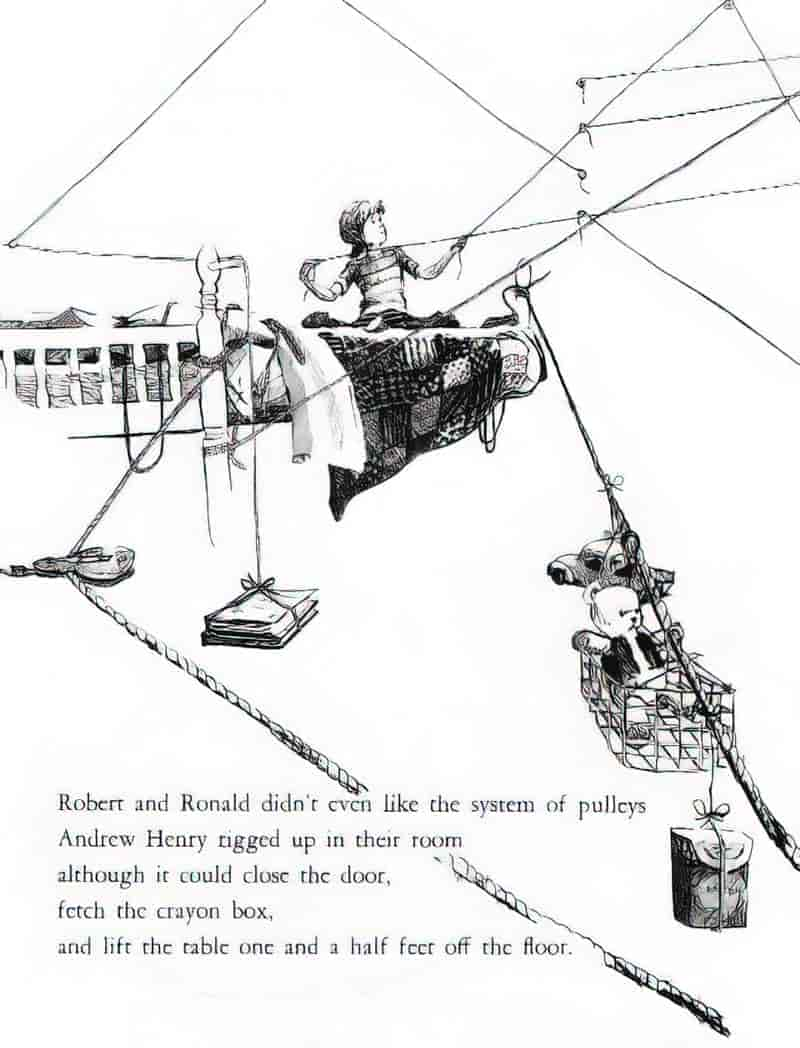

But the intro isn’t boring anyway, because Andrew Henry is a genius at building things and the things he builds are fun.

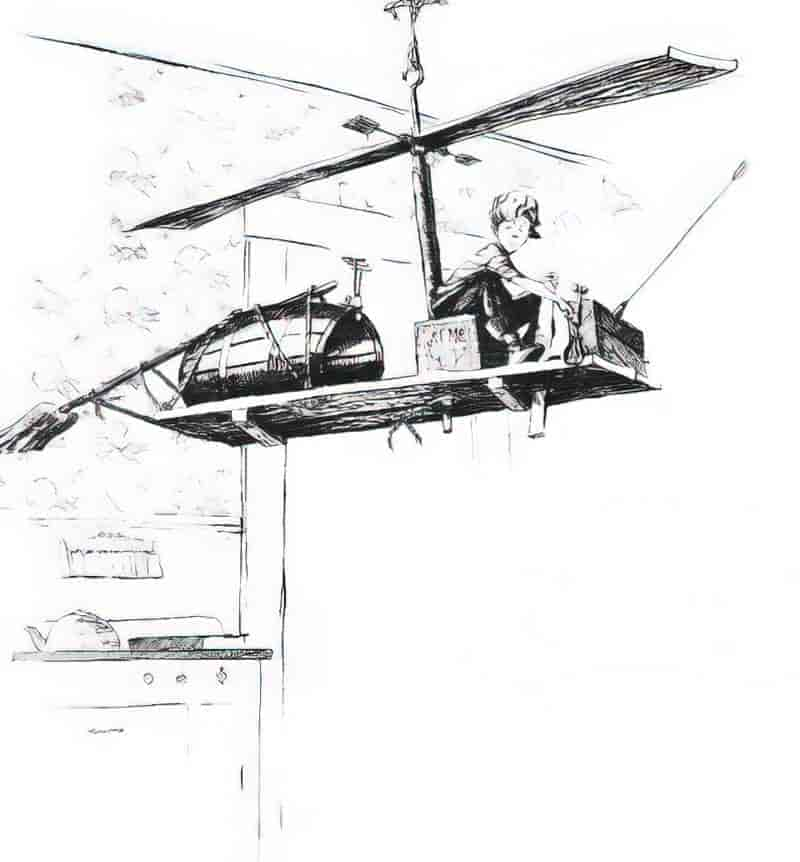

Mrs Thatcher (a name which garnered new connotations in the post 1980s period) does not appreciate the helicopter in her kitchen and tells Andrew Henry to take ‘that thing’ away because she has work to do. She’s not worried about the entire thing falling off the ceiling and crashing into the floor, injuring her boy, which reminds me of the plastic bag scene from Mad Men (a comment on how differently 20th century parents viewed safety):

Andrew Henry’s older sisters don’t want him messing with their sewing machine, either. Andrew Henry is getting into everyone else’s spaces and things.

ANDREW HENRY AND AUTISM

Andrew Henry’s singular focus and his feeling of being different make a good metaphor for neurodivergence, e.g. autism. But as with many things autism related, almost all children can relate to:

- sometimes feeling alone even within the safety of a family

- having passions which encroach on other people’s space

- being really into something and no one in your orbit appreciates the skill involved

- the fantasy of leaving home for good when friction occurs (“That’ll teach em.”)

- the urge to collect things related to your passion

THE SWITCH TO SINGULATIVE

One fine spring morning he made up his mind. Quietly he gathered together his tools. He packed his hammer and his saw, his pocket knife and pliers, and a big sack of nails, some bolts, nuts and wire, and even a few lengths of stovepipe.

Andrew Henry’s Meadow

Then he leaves home. Only the dog sees him go. He plans to build a house for himself. He knows where he’ll build it. He knows just the meadow. He walks ‘kitty corner’ through Burdock’s pasture. I’d never heard that phrase before in that context before. I understand that kitty (or catty) corner refers to two things placed diagonally opposite each other, but had not considered that someone might ‘walk kitty-corner’.

To walk kitty-corner is to cut across, jay-walk, or somehow take a shortcut.

What’s this to do with cats? Anything? (Cats also like to take shortcuts, through other people’s back yards.)

The word has nothing to do with domesticated felines. Rather, it stems from the word cater-corner. Cater is an English dialect word meaning “to set or move diagonally.” It is derived from the French quatre, which means “four” or “four-cornered.” The word quatre was first introduced to the English as the word for the number four on dice, and was promptly anglicized to cater. Early versions of cater-corner were “caterways” and “caterwise,” which meant the same thing.

Today I Found Out

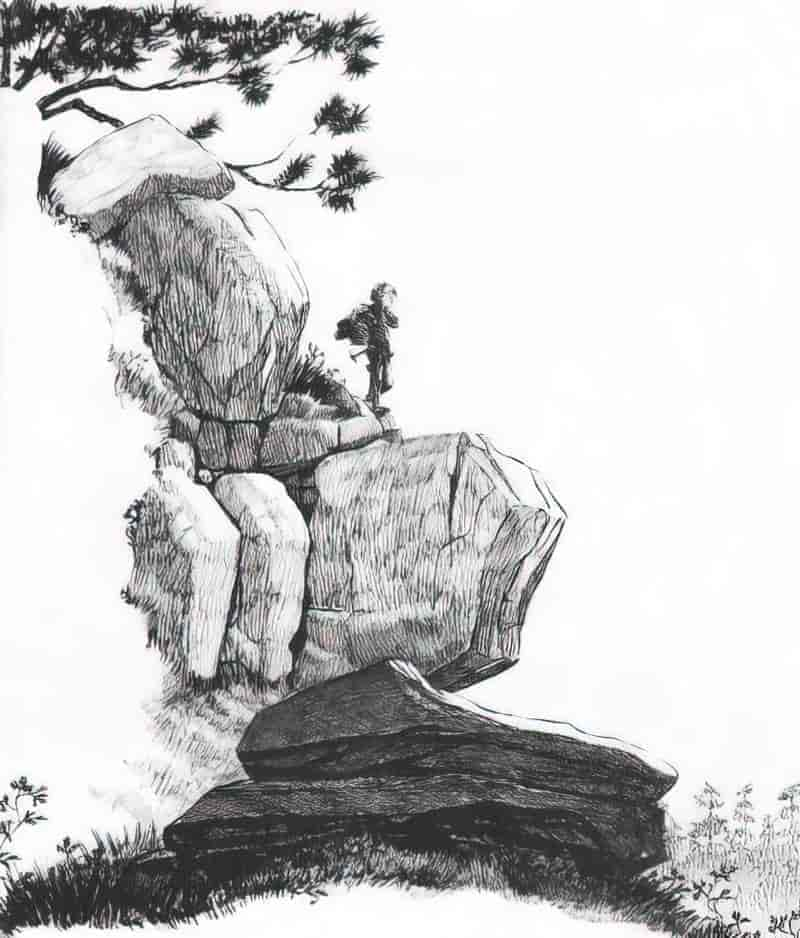

He climbs up over Blackbriar Hill, onto some beautifully rendered rocks. In stories, when characters gain altitude, they’re coming to terms with something, having an epiphany, getting a new perspective on things. (Ostensibly he’s surveying the best place to build a hut.)

Andrew Henry pretty much traverses all of the major geographical features you might find in the Midwest. He traverses Worzibsky’s Swamp and enters the ‘deep woods’. The woods is, of course, a metaphor for the subconscious. This journey to the meadow represents the torment involved in Andrew Henry’s decision to leave his family. (He plans to leave them forever.)

He finds a tall fir tree, straight and strong, a good example of how fir trees symbolise determination, honesty, and the endurance that comes with hope for the future.

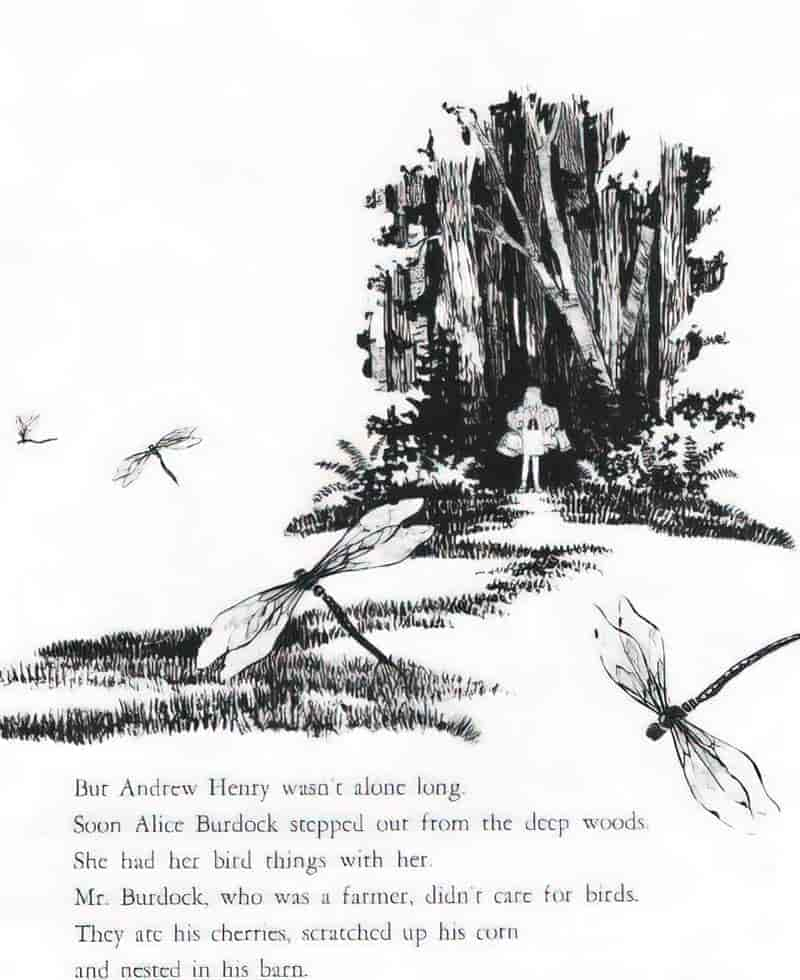

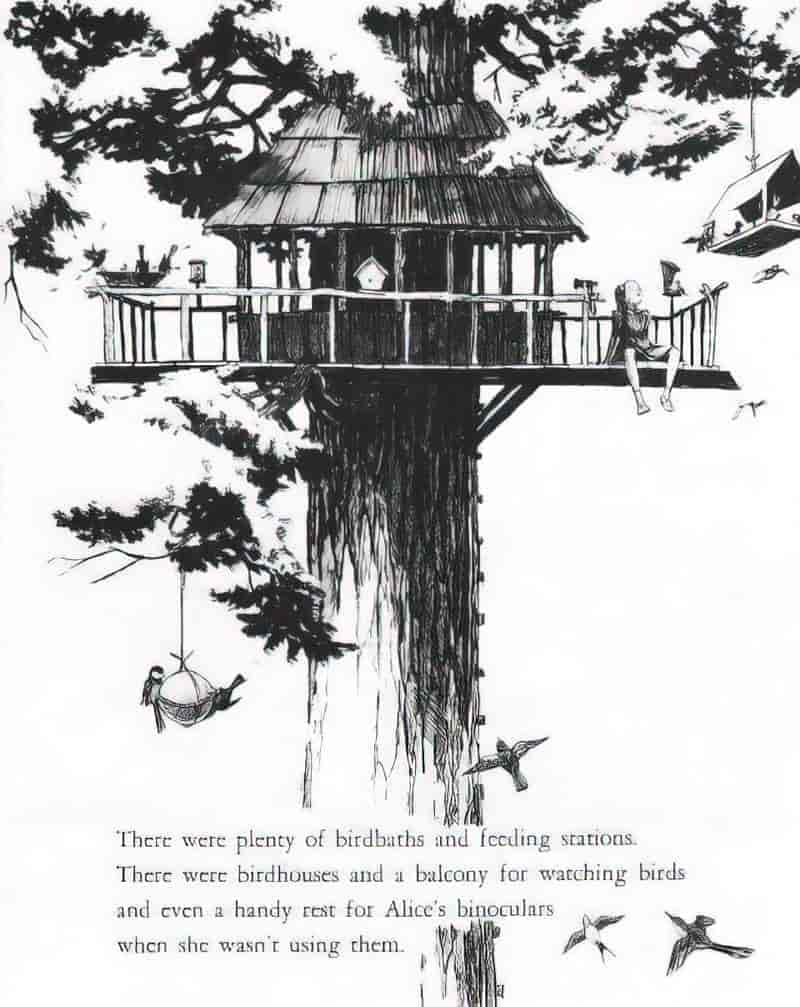

Andrew Henry finds his new family. Turns out the village of Stubbsville is chock-a-block full of children whose passions are discouraged by their parents.

They all turn up to join Andrew Henry in his meadow. Andrew Henry builds an entire separate village of huts and shelters.

Eventually the parents notice some of the village kids missing, so they all set out on a search.

For four days and four nights everyone searched frantically.

Andrew Henry’s Meadow

I’m always interested in why storytellers settle on certain numbers and not others. Why nine huts built by Andrew Henry, for instance? Well, I figure if the number were ten, it would seem that the story itself were waiting for ten missing children before anyone cared to look. Ten feels too neat. Nine feels perfect. With regards to the four days and nights, I think it’s just important that it’s not three. Three would feel too unnecessarily Biblical. Two nights isn’t long enough for the kids to feel they’ve had a decent go of camping out alone.

It’s the dog who tracks Andrew Henry with his nose. He’d been told to stay put, but loneliness overcomes him. The entire town and their pets run ‘kitty-corner’ after him, and now we get a good visual representation of what running kitty-corner looks like. It would seem to mean ‘run in a zig-zag path’. Could my Internet searching have led me wrong? If I run kitty-corner to the shops, will I get there sooner or later than just walking straight?

When Andrew Henry is welcomed back into the family home, we can deduce that his experience doing things for other (like-minded) kids has made him a more empathetic person when it comes to his family. He now respects their spaces, and this time he builds them things they would like, rather than filling up their spaces with things he finds interesting.

The Thatcher family gives their proto-engineer son a corner of the basement behind the furnace to do his building work, which is why I, as a New Zealand kid, always longed for one of those wonderful basements I saw in North American children’s literature. New Zealand houses do not typically have basements (or furnaces, for that matter). Nor do they have attics, and it would seem from children’s literature that all the coolest things happen in attics and basements.

SEE ALSO

Doris Burn also illustrated a book called We Were Tired Of Living In A House, written by Liesel Moak Skorpen, three years later in 1969.

In 1968 The Summerfolk was published, also written and illustrated by Doris Burn. In this story, Willy Potts lives with his dad Joe in a shack on a beach. The beach becomes filled with ‘summerfolk’, meaning tourists who are only there for summer. Willy and Joe want nothing to do with the summerfolk until Willy makes an eccentric friend. Perhaps this is the picture book analogue to Shirley Jackson’s terrifying short story “The Summer People“?

In any case, one thing is clear: Doris Burn had a thing for what we might call ‘vanishing houses’. Is that what you call temporary houses? I’m riffing here on ‘vanishing art’ (art done on the backs of paper napkins etc. because it’s not meant to be permanent).