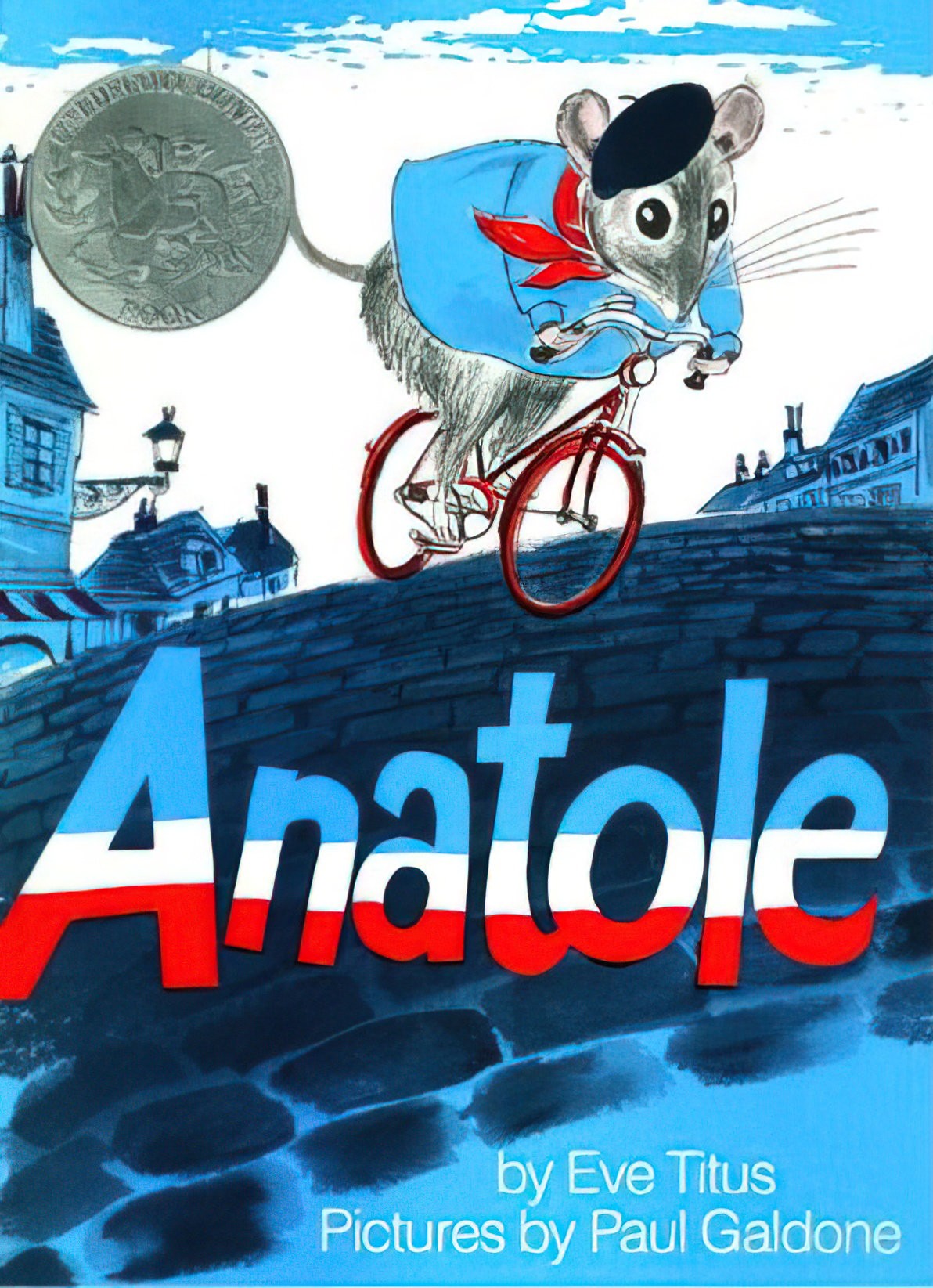

Anatole the mouse starred in a series of children’s stories by Eve Titus, illustrated by Paul Galdone in blue, red and white. The ten books were published 1956-1979. Today I’m taking a look at the picture book that opened the series. Anatole was named a Caldecott honour book.

If you love cheese, it’s likely you’ll love Anatole. However, I’d encourage readers to look more carefully at the ideology hiding behind all that delicious cheese.

SETTING OF ANATOLE

The setting of Anatole is significant. Like many picture books, including some written today, Anatole is set in a utopian parallel 1950s universe, in which all a man needs to be perfectly happy is a supportive wife at home, many children, and a way of earning a living to support them.

We are told in the opening pages that Anatole lives in a parallel mouse world, which is a miniature replica of human world — they have their own miniature houses in their own village. The difference is that the mice ride bicycles rather than drive cars, but then, this is a book set in a fictional version of France. Eve Titus was American. What do non Parisians think of Paris? We think, naturally, that Parisians go everywhere by bicycle. This is a cute tweak on mice who generally scurry about all fours, quite uncutely, in my personal experience.

STORY STRUCTURE OF ANATOLE

PARATEXT

Anatole is a most honorable mouse. When he realizes that humans are upset by mice sampling their leftovers, he is shocked! He must provide for his beloved family—but he is determined to find a way to earn his supper. And so he heads for the tasting room at the Duvall Cheese Factory. On each cheese, he leaves a small note—“good,” “not so good,” “needs orange peel”—and signs his name. When workers at the Duvall factory find his notes in the morning, they are perplexed—but they realize that this mysterious Anatole has an exceptional palate and take his advice. Soon Duvall is making the best cheese in all of Paris! They would like to give Anatole a reward—if only they could find him…

MARKETING COPY

SHORTCOMING

They are a disgrace to all France. To be a mouse is to be a villain!

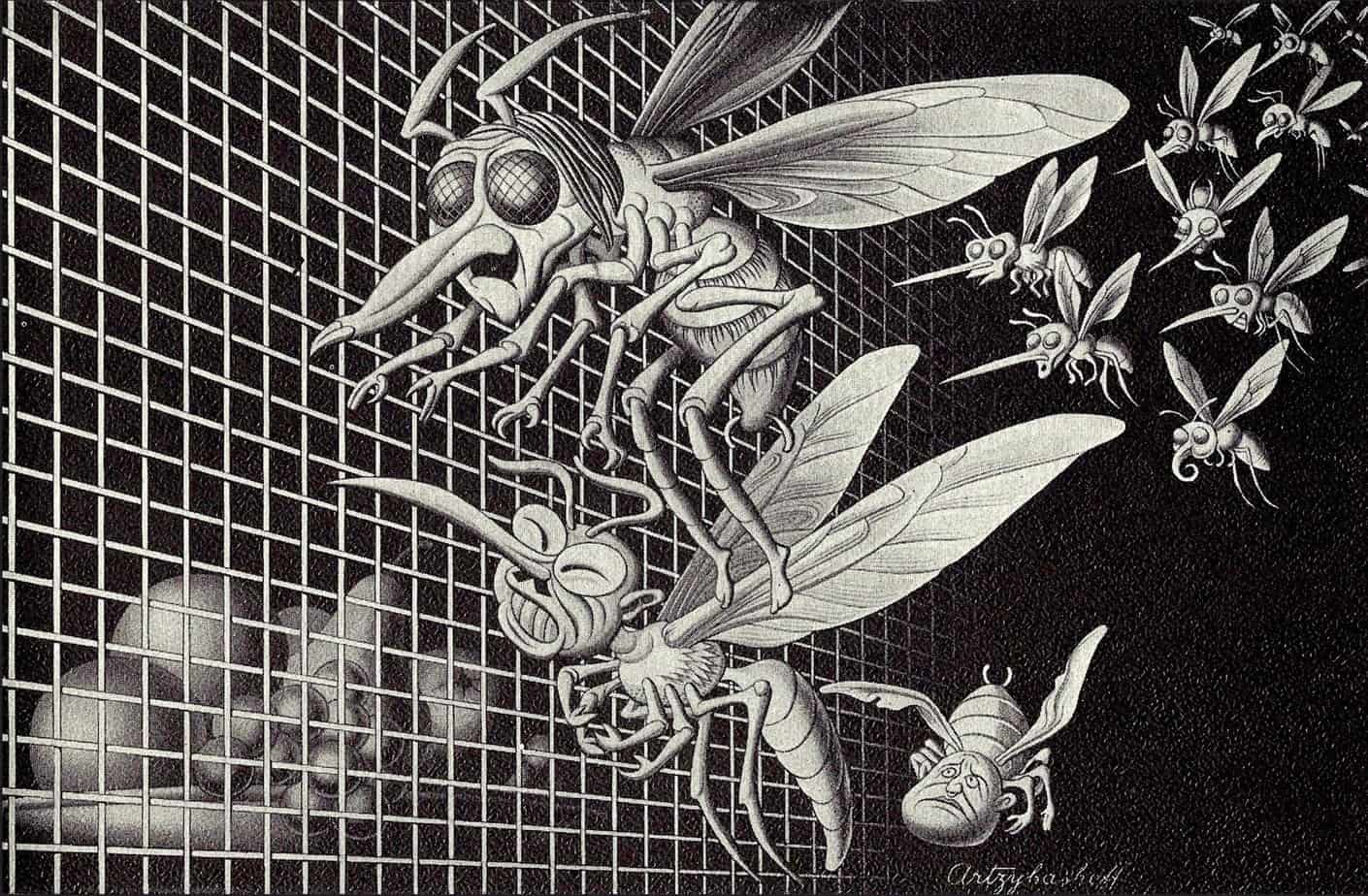

Anatole the mouse is heroic and resourceful. His only problem is that he his hated by humans. The mouse/human dichotomy will put the adult reader in mind of fascism. One important stage of fascism occurs when dictators portray less powerful groups of people as vermin, insects or other unwanted creature.

This tactic is still, dangerously, used by dictators (or wannabe dictators) today.

In response, some artists have turned this messaging on its head, as in the illustration below.

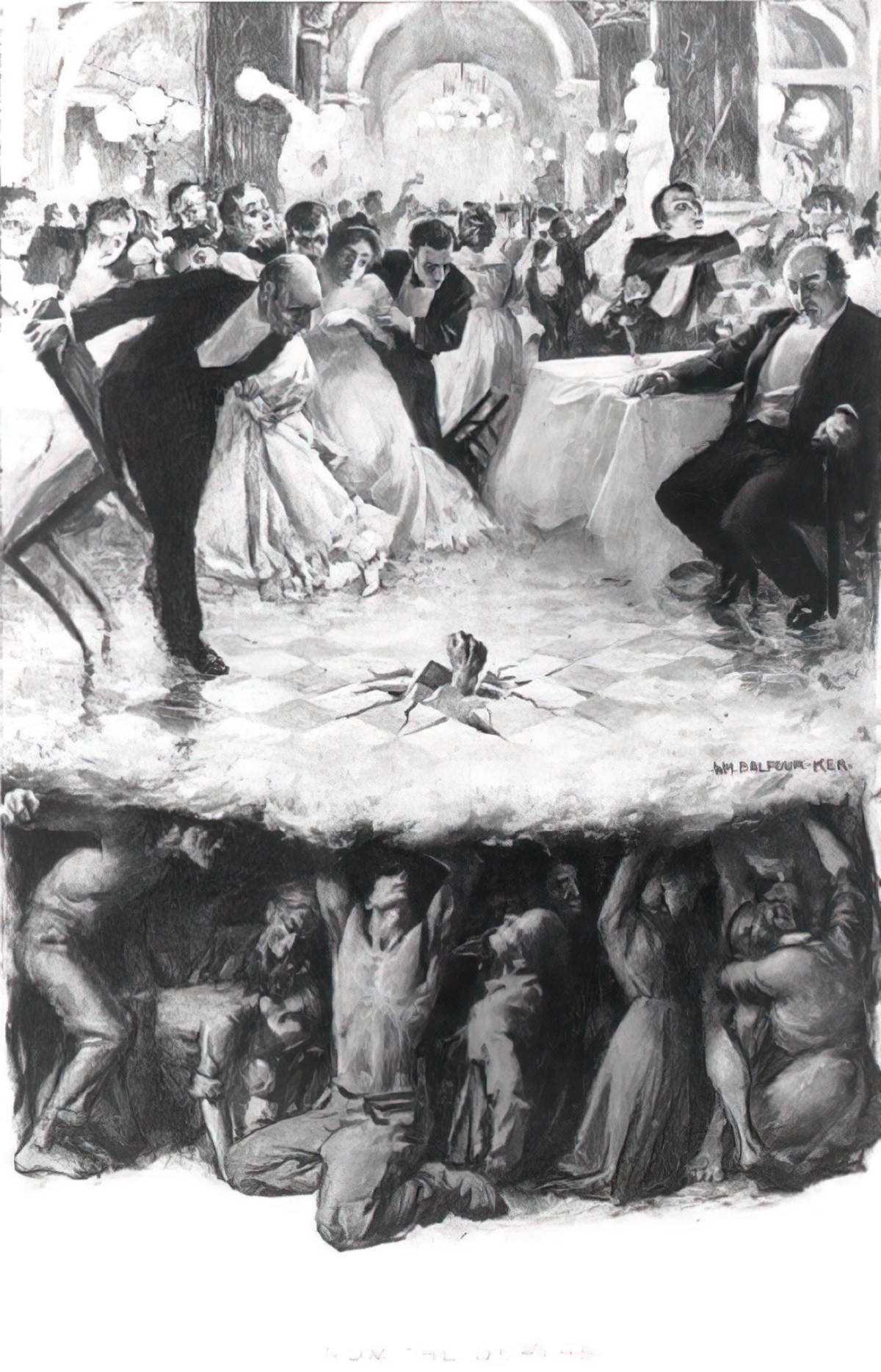

The situation of Anatole reminds me a lot of the image below, in which the poor working class props up the wealthy while the wealthy remain oblivious — until, every now and then, something happens to remind them.

Income inequality is worse now than it was when Anatole was written. Anatole’s main problem is that he is of the hated underclass, and the moment he realises this fact (by overhearing a woman complain about mice), he understands the peril he is in.

DESIRE

Anatole wants to continue living his perfect life as it was before his unfortunate revelation. He wants to continue to provide for his wife and children. The ending of the story shows how important his wife’s opinion is to him; her admiration is the admiration he craves the most.

OPPONENT

The Minotaur opponents are humans. The reader doesn’t know how these humans will react if they find out a mouse has been running all over their precious cheeses.

Aside from a Minotaur opponent, a good story requires conflict between in-group characters. When Anatole tells his friend Gaston what he has overheard, the author is making use of a common scene you’ll see everywhere, and in pretty much every Hollywood movie: The main character talks to the best friend, and together they have a disagreement about the reality of the situation. This scene seems to be necessary in helping an audience to sink into the reality of a story, or as we might say, a necessary step in creating verisimilitude. The audience is not there to query the main character ourselves, or to present a different take on ‘reality’, or to point out all the problems with the plan.

PLAN

As in a heist plot, the reader sees Anatole carry out his plan, but we have no idea what he plans to do with those little signs. (Technically, the wife inspires the idea. ‘Behind every great man is a great woman…’)

The audience is left in audience inferior position, which helps us see how smart Anatole’s plan is. His plan: He will become a secret cheese critic. Although this aspect is not on the page, I imagine a rodent who could write would be an excellent critic. Like dogs and various other mammals, they have a most excellent sense of smell.

The premise of this book rests on the (incorrect) idea that mice love cheese. Mice will eat anything, including cheese, but when offered a selection will go for grains and carb-heavy foods before touching the cheese. This fact is irrelevant to the story of Anatole and other mouse stories like it.

THE BIG STRUGGLE

It turns out that the most powerful human of all, the company boss, is a benevolent character who not only realises the secret cheese taster has led directly to increased sales, but who doesn’t take full credit for it himself. Frankly, this is unusual among CEOs.

Until now, the story of Anatole has functioned a little like later (modern) versions of The Elves and the Shoemaker, but in the classic fairytale, the shoemaker discovers the identity of the elves. Eve Titus keeps the identity of the mice hidden, in a rare example of a story in which the narrative mask never comes off.

The pleasure of doing somthing secretly special appeals to kids, and can also be seen in Sidewalk Flowers, a Canadian wordless picture book. In that story, too, the mask never comes off. More than that, no one seems to notice the girl has left the flowers. There is precisely zero outside validation in that particular story, which nonetheless works beautifully.

ANAGNORISIS

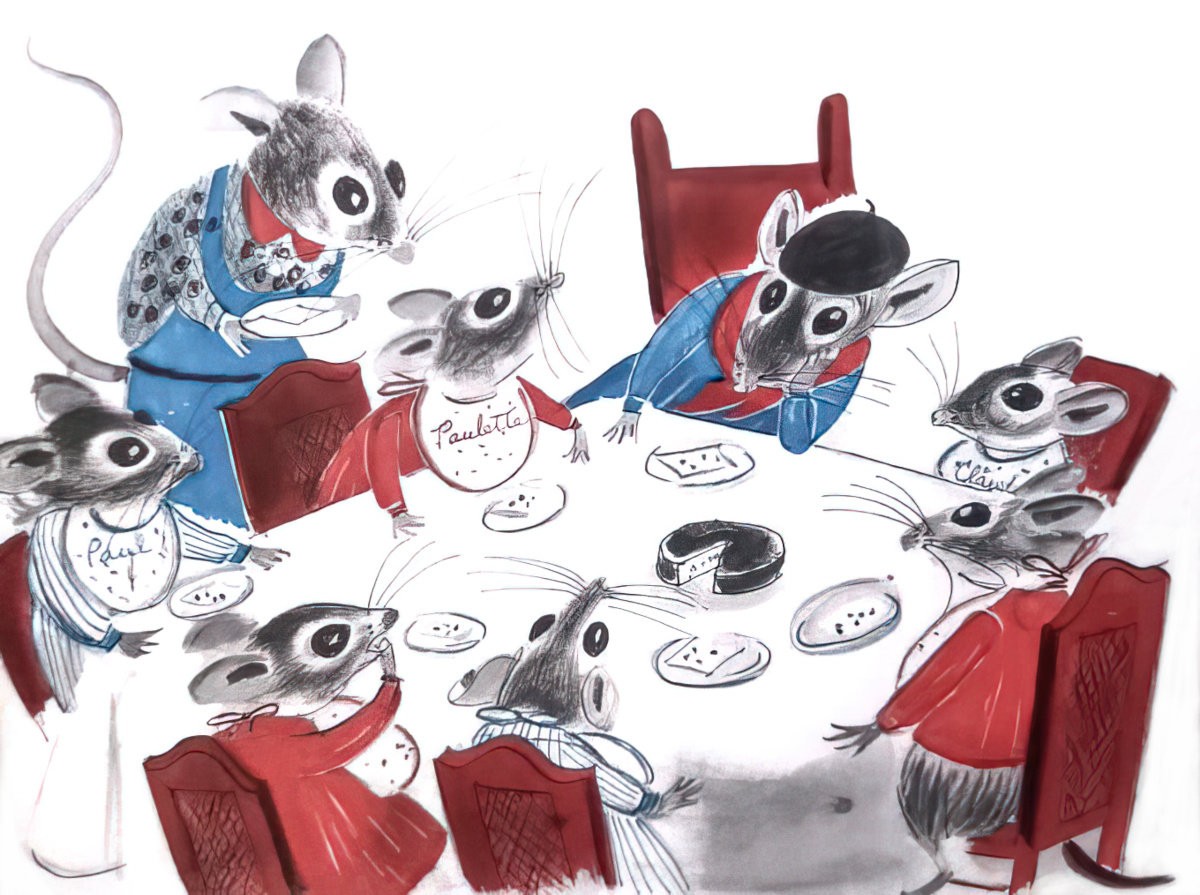

In Anatole, the storytelling requirement that ‘masks come off’ is in fact fulfilled, because Anatole is widely revered by his own family and wider mouse community for coming up with such an ingenious plan. Notice how several pages are dedicated to extolling the virtues of Anatole? I believe that’s compensation for subverting reader expectations in the unmasking phase.

NEW SITUATION

Anatole’s social capital has shot right up.

Here’s my refrigerator moment: If the humans don’t know it’s the mice doing them this huge favour, don’t they still hate the mice? Why would they not try to exterminate them, by attaching traps to the cheeses they so clearly want to be nibbled by mice, since they’re leaving them out, uncovered, all night?

EXTRAPOLATED ENDING

We don’t need to extrapolate what happens to Anatole because there was an entire series to follow. I believe Anatole’s resourcefulness comes to the fore in each of the stories — an early, mouse-like MacGyver or Walter White.

Eve Titus’s Anatole manages to combine cheeky thieving with being a human friend — a situation which is not at all unknown. Anatole and his friends are contemporary characters [ie 1970s] — wherever humans are, there they will be. Their adventures are a comic mixture of fantasy and mouse action. Anatole is an important mouse, friend of humans, chief taste at Duval’s cheese factory. He changes his apparent size at will, with no questions asked — he and his wife and six children can go on a cycling holiday or dash to and fro on their bicycles to round up smuggling criminals. But they can use their small size to hide, explore and listen, and throughout are seldom seen. They write notes to the police and live in a mouse village of miniature French houses — a real Snug Town that is somewhere in limbo, or hidden; no cupboards, wainscots or cellars for them. This, to me, has neither one kind of reality nor the other, and for all its amusement has not the true charm of the genre.

Margaret Blount, Animal Land, 1974

RESONANCE

Where is my self-respect, my pride, my honour?

The ideology that work affords one dignity is popular, mainstream and therefore prominent across children’s literature. Anatole the mouse is revered by his community because he has made a plan, worked to carry it out successfully and provides for his family.

This ideology is problematic once a society no longer needs the full-time full employment of humans in order to function well, resulting in a large proportion of un- and underemployed working age adults who can no longer work even if they would love to.

The strong, unshakeable connection between work and dignity is something I’d like to see gone in contemporary stories for children. Everyone deserves dignity, even the powerless (mice) of society, just for being themselves.

I also believe it is a dangerous to teach young people that they will be richly rewarded so long as they work hard for the man. Anatole’s plan is basically to give the humans ‘something in return’. So long as he makes humans’ lives better, they will spare him, he reasons. (His reasoning is borne out.)

This is a slightly more subtle version of ‘the meek shall inherit the earth’, aka, ‘don’t rise up against the more powerful classes who would very much like to exploit you’. But by observing reality, we can see that this ideology does not transfer to the real world of work. It never really did, and certainly does not today.

Jeff Bezos, World’s richest man, wants your donations to help Amazon employees.