Allegory means, among many other things, that the characters, worlds, actions and objects in a work of fiction are highly metaphorical. That doesn’t mean they aren’t unique or created by the writer. It means the symbols have references that echo against previous symbols, often deep in the audience’s mind.

Allegorical also means ‘applicable to our modern world and time’.

Good stories have elements that are founded on the thematic line and oppositions. This especially applies to allegory. For example, for Tolkien, Christian thematic structure emphasises good versus evil.

What’s The Difference Between Allegory And Symbolism?

An allegory is a story told by a symbol’s POV, or a highly symbolic story. Allegory = ‘extreme metaphor’.

Symbolism is a bit more subtle, and will be interpreted in a range of different ways by different readers, as Thomas C. Foster explains below:

Here’s the problem with symbols: people expect them to mean something. Not just any something, but one something in particular…It doesn’t work like that. Oh, sure, there are some symbols that work straightforwardly: a white flag means, I give up, don’t shoot. Or it means, We come in peace. See? Even in a fairly clear-cut case we can’t pin down a single meaning, although they’re pretty close. So some symbols do have a relatively limited range of meanings, but in general a symbol can’t be reduced to standing for only one thing. […]

[With symbols, however,] the thing referred to is likely not reducible to a single statement but will more probably involve a range of possible meanings and interpretations. [A symbol requires] of us…to bring something of ourselves to the encounter [in order to get its meaning].

How To Read Literature Like A Professor by Thomas C. Foster

With allegories, on the other hand, there is generally a commonly accepted symbolic meaning. It’s harder to come up with your own unique interpretation (and justify it).

Examples of Allegory

Strict allegory, in which virtually every word must support a double meaning and fit into a coherent interpretation, has produced few examples since the Middle Ages. But loose allegory, in which only major events and characters must fit the chosen ideological pattern, still appears with fair frequency and is a staple of experimental, literary fiction, and fantasy.

Lord Of The Rings is fantasy but applied to a wartime 20th century world. (Tolkien said he didn’t mean to write it as an allegory of war, but he was a product of his time.)

Lord of the Flies is, in large measure, a fable of this sort. Each of the major characters represents one particular facet of hu- man possibility as Golding conceives it. The characters are stranded on an island to limit them to their own resources. They’re schoolboys (some are choirboys) to underline that they’re as close to innocence as human beings are apt to get. And all are male, I assume, to keep any question of sex from muddling the experiment, since it’s not part of what Golding wants to examine. They’re boys. But boys plus. Simon, for example, is a fully realised individual. But he also stands for and demonstrates the mystical and hopeful tendencies in all people. He’s the only mystic on the island, just as Piggy is the only intellectual, Jack the only natural hunter, Roger the only sadist, and so on.

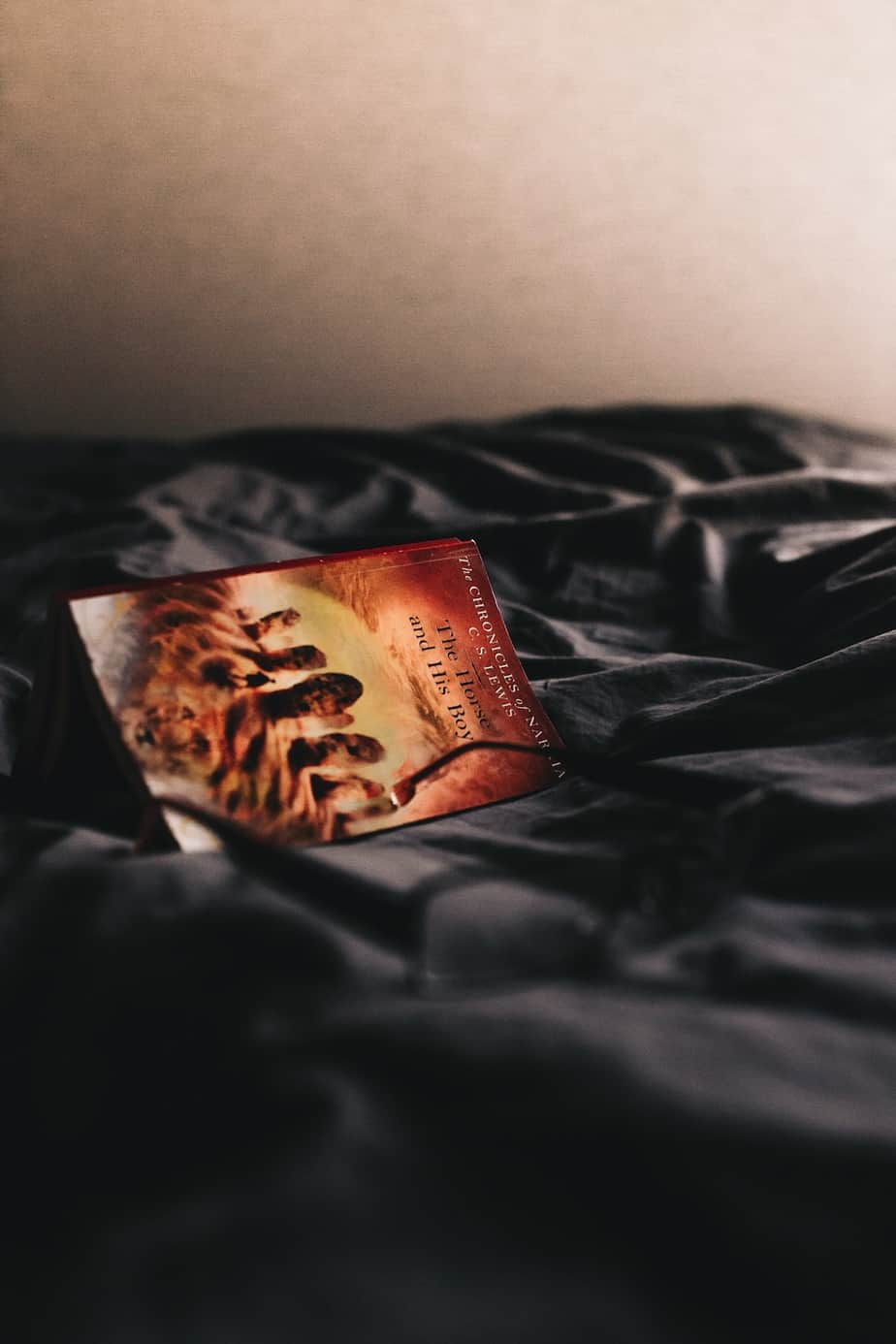

Narnia — Aslan stands for a concept beyond his role — Jesus, of course. But as Roger Sutton writes in his article about the allegory of The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe, there is a contradiction involved in writing allegory for kids:

There’s a reason we caution would-be writers for children to stay away from allegory, and it’s the same reason we see so much of it from self-published and small-pressed* children’s authors: it’s more often preachy and didactic and labored than not, but there’s a lesson involved, which people who don’t love to read love to see in books for the young. Allegory also, as we see above, eludes many young readers, so what’s the point?

Roger Sutton, November/December 2019 editorial at The Hornbook

Animal Farm — an allegory about capitalists and totalitarians. This 1945 novel is popular among many readers precisely because it’s relatively easy to figure out what it all means. Orwell is desperate for us to get the point, not a point. Revolutions inevitably fail, he tells us, because those who come to power are corrupted by it and reject the values and principles they initially embraced.

Aesop’s Fables — In its simplest forms, allegory can be a fable like that of the dog in the manger or the fox and the grapes, in which dog, fox, grapes and manger stand for some reality of human experience—that some people who can’t use a thing nevertheless are reluctant to let others enjoy it; that some people rationalise their disappointment at being unable to get something by claiming the thing is no good anyway.

Pilgrim’s Progress — Back in 1678, John Bunyan wrote an allegory called The Pilgrim’s Progress. in it, the main character, Christian, is trying to journey to the Celestial City, while along the way he encounters such distractions as the Slough of Despond, the Primrose Path, Vanity Fair, and the Valley of the Shadow of Death. Other characters have names like Faithful, Evangelist, and the Giant Despair. Their names indicate their qualities, and in the case of Despair, his size as well. Allegories have one mission to accomplish—convey a certain message, in this case, the quest of the devout Christian to reach heaven. If there is ambiguity or a lack of clarity regarding that one-to-one correspondence between emblem—the figurative construct—and the thing it represents, then the allegory fails because the message is blurred.

Pinocchio — an allegory of life, similar to The Water Babies and The Three Pearls, but far nearer to folktale in feeling due to its shadeless black and white issues and quick rewards of virtue and sharp punishment of wrongdoing. Pinocchio can be considered a young Pilgrim’s Progress. There are animal tempters, avengers and judges. Pinocchio is always saying, “Oh! How I wish I could have been a good child!” Obedience brings you to heaven, the reverse gets you nowhere.

Features Of Allegory

SUBTEXT

Like a theme story, allegory has a subtext, a pattern of meaning beyond what’s evident on the surface. Just more so.

LOTS AND LOTS OF SYMBOLISM

Allegory involves creating a fairly thoroughgoing pattern of symbolism in which all major events and characters in a story have a meaning beyond themselves and those meanings can be put together to make some sort of overall sense.

This kind of structural symbolism lends itself to social satire, political polemics, fantasy, and religious fiction. There are innumerable examples of each. Some are plotted; some derive their energy from the tension between symbol and reality, the character and what the character stands for, the gradual revelation of larger meanings.

Allegory = Extreme Metaphor

To see how metonymic and metaphoric devices interact in a mixed, that is, both realistic and romantic, fiction, it is perhaps best to begin with the extreme form of the metaphoric or romance pole, the allegory. In an allegory, the only way to approach the characters is by reference to their position in a preexistent code. An analysis of the metonymic context leads nowhere. […] if we were to meet an allegorical character in real life, we would think the person driven by some central obsession. The obsessive-like behaviour of the character is, of course, a result of his or her actions being totally determined by the position he or she holds in the preexistent code. The difference between an allegorical character and a character in a romance is that the romance figure not only acts as if obsessed because of his or her position in the story but also seems obsessed in reference to the similitude of real life created in the work itself.

This combination seems most effectively achieved when a psychologically real character’s obsession is so extreme that he or she projects the obsession on someone or something outside the self and then, ignoring that the source of the obsession is within, acts as if it were without. Thus, although the obsessive action takes place within a similitude of a realistic world, once the character has projected an inner state outward and then has reacted to the projection as if it were outside, this very reaction transforms the character into a parabolic rather than a realistic figure.

The most obvious early examples are those stories by Poe that focus on “the perverse”, that obsessive-like behaviour that compels someone to act in a way that may go against reason, common sense, even the best interests of the survival of the physical self. In many of Poe’s most important stories, the obsession occurs as behaviour that can be manifested only in elliptical or symbolic ways. For example, in “The Tell-tale Heart” the narrator’s desire to kill the old man because of his eye can be understood only when we realize that “eye” must be heard, not seen, as the first-person pronoun “I”.

Charles E. May, The Art of Brevity

The Challenges Of Writing Allegory

There are two main dangers with this kind of fiction, from Ansen Dibell’s Elements Of Plot:

1. The message, the larger meaning, will take over, making the characters seem like lifeless puppets and the story, however organized, a mechanical thing determined by forces imposed from outside—a political stance, a religious or social ideology. The fiction has a blatant ulterior motive. In extreme cases, the events and people of the story, as presented, make no surface sense at all. Only what they stand for is of any significance; and that’s not enough to make the story readable or coherent.

2. The second difficulty is establishing the system of symbols itself. The pattern must make sense, rather than seeming an arbitrary authorial whim (umbrella = ambition; galoshes = passionate love; fish = space travel). The symbols chosen must be appropriate both to what they represent and to one another. The connections should be valid and reasonable in a plain literal sense as well as a metaphorical one, and be consistent through the whole story. A knife can be a symbol; but it also better be able to cut string. And if it represents cutting free, cutting loose, in the story’s beginning, it better not be used to prop up a bookcase and then forgotten, later on.

In practice, this makes characterisation and plotting doubly hard, since each element of the story carries an added weight of meaning and invites interpretation, as though it were a code to be broken rather than a story to be enjoyed.

Both difficulties, combined with allegory’s tendency to become preachy and polemic and its requirement that the reader put in extra work discerning the second level of meaning, have diminished its popularity over the centuries.

FURTHER READING

The Baby’s Own Aesop, illustrated by Walter Crane