“All She Said Was Yes” is a short story by Shirley Jackson. This is the one with the Wednesday Addams character archetype who foresees the death of her own parents. But do they listen to her? No.

The story is told from the point of view of a neighbourhood gossip, who inserts herself into the tragic drama of her next door neighbours — who she never liked. She especially never liked the daughter, but here we are. Someone needs to step in and perform the social labour of mothering a creepy girl who has not shed one tear about her poor, dead parents (who had it coming, since they drove so erratically).

I’m a careful driver (I’m a reckless driver)

“Reckless Driving”, song by Ben Kessler and Lizzy McAlpine

And I tell you all the time (you tell me all the time)

To keep your eyes on the road (to keep my eyes)

But you love me like that (do you love me like that?)

You’re a reckless driver (if I keep on driving)

And one day it’ll kill us (would you hold me when we crash?)

If I don’t let go

Shirley Jackson was good at writing these women. She can’t have liked them very much as friends because they tend to get their comeuppance. The woman from “Home” is another Shirley Jackson example from the same Dark Tales collection. (I call these characters the Gossiping, Busybody Archetype.)

POST-READING QUESTIONS

- How is the narrator shown to be unreliable? In which ways is she wrong about herself and about the situation?

- Who are the most sympathetic characters in this short story?

- What is the story function of Mrs Wright? What does she illuminate about the narrator?

- Do you think Little Dorrie is how her mother conveys her? What can you find in the text which leads readers to doubt the mother’s take on things?

- This is a supernatural story. A fifteen-year-old girl can see the future. How does this ability work according to world of the story?

- “All She Said Is Yes” contains irony and also paradox. What can you spot?

- How does Shirley Jackson show us throughout the story that the narrator has ‘no choice’ but to go on the cruise?

- This short story is an allegory for mid-century cultural anxieties. What were people very worried about as this story was written? Do you think people worry less about Armageddon now, or more? How has the nature of worry changed? stayed the same?

WHAT HAPPENS IN “ALL SHE SAID WAS YES”

You shall know the truth, and the truth shall make you odd.

Flannery O’Connor

THE WEDNESDAY ADDAMS ARCHETYPE

In the mid twentieth century, Shirley Jackson, Charles Addams and Ray Bradbury (for starters) were all creating weird American teen girl characters for the popular imagination. And these girls were popular.

Vicky Lanson is a Wednesday Addams archetype, with a twist. Shirley Jackson herself lived in a larger body, and unlike Wednesday (who is tiny), Vicky has a healthy appetite and our unnamed narrator next door judges the girl for continuing to eat, even in the wake of her parents’ tragic death. These archetypes tend to be pretty, juxtaposed against their tough, uncaring persona — an ironic take on the beauty equals good narrative of fairy tales. But Shirley Jackson must have seen enough of the ironic takes. Vicky is large.

I’ll randomly name the narrator Jean, only because I get sick of typing ‘unnamed narrator next door’.

So, Jean has never really liked her neighbours. Written in a conversational tone, “All She Said Was Yes” opens with a rundown of history between the two households.

Basically, Jean has had to put up with the Lansons because of proximity, and because her own daughter, “our Dorrie” grew up with Vicky. Readers understand very quickly that this is a judgemental, biased narrator so we must fill in the fuller picture for ourselves.

The Lansons seem happy-go-lucky and socially popular, but also reckless and not especially in tune with their daughter. Unlike Jean, who spanks her own daughter, the Lansons at least try. We can deduce they’ve engaged a psychologist to deal with Vicky. Jean has no time for all this ‘psychological jargon’.

The paragraph above made me laugh, and also prefigures Jean’s later refusal to believe she is going to die. She uses the word ‘if’. Of course she is going to die (at some point) and it is very likely she will die before her own daughter. But she says ‘if’. She hasn’t accepted reality yet, which puts her emotionally and psychologically in a less mature mindset than the fifteen-year-old girl before her.

Jean adores her own perfect daughter. Jean’s own daughter is barely there. The absent, perfect daughter exists in Jean’s imagination. Dorrie is at camp while the parents plan a (cancelled) holiday to Maine. Do they ever see her by choice? Even when Dorrie is at home, we can deduce that Jean doesn’t see the real Dorrie, who is probably up to all sorts of mischief at camp, and probably has far more in common with Vicky than Jean will ever know.

And why has their holiday to Maine been cancelled? Because the fools next door have only gone and got themselves killed in a car wreck, leaving behind a teenage daughter who needs taking care of. And who else will do it? Jean must martyr herself until extended relatives arrive to take the reins.

Jean girds her loins and pops next door, ready to offer comfort to a distraught and weeping Vicky Lanson. But that’s not what she gets. Vicky has been expecting this. She is cool, calm, collected and angry. She warned her parents against driving recklessly. But would they listen? No.

THE TITLE

Well, so far she hadn’t said a word, not a single word since I came through the door, and now all she said was, “Yes.”

“All She Said Was Yes” by Shirley Jackson

… if this child could sit there coolly not five minutes after hearing that her parents had been killed in an accident and make plans for her future — well, all I could say is that maybe some of Helen Lanson’s psychology paid off, in a way she might not like so much, and I just hope that if ever anything happens to me, my daughter will have the grace to sit there and shed a tear.

“All She Said Was Yes” by Shirley Jackson

Vicky also knows, due to premonitions which she is happy to share, that her aunt will soon arrive to pick her up, but in the meantime she’ll be staying in Jean’s daughter’s bedroom.

“All she said was yes” suggests a clockwork nature to decision making. This will extend to Jean herself. Yes, the trip to Maine was cancelled. Yes, she’ll be forced to take another holiday before she feels all is right with her world. Yes, it will be on the water…

“It’s a terrible thing,” I told him, “a terribel thing to happen anytime, of course, but wouldn’t you just know they’d go and do it now?”

“No help for it. We’ll have to try and plan something else.”

“All She Said Was Yes” by Shirley Jackson

COLD MOTHERS, COLD (ABSENT) DAUGHTERS

In contrast to the women in the story, the men are more empathetic. The doctor understands the processing delay of trauma. The husband, Howard, understands that grief doesn’t always show on the outside. I think a mid-century man would realistically understand that better than someone like Jean, since men, by the dictates of masculinity, are required to keep all negative emotions inside, except for anger. Mid-century women had their own repressive rules of behaviour, as evinced comically by Jean, who complains that the bereft, 15-year-old houseguest hasn’t done any vacuuming or dusting:

I had to forgive her, of course, because of the sad blow she’d had, but I’d just like to see my Dorrie act like that no matter what happened. I mean, even if I was dead it would give me comfort to know that my daughter didn’t forget her training, and the nice manners I taught her.

“All She Said Was Yes” by Shirley Jackson

Again, her own death is a hypothetical concern for Jean.

No matter how much you’ve been warned, Death always comes without knocking. Why now? is the cry. Why so soon? It’s the cry of a child being called home at dusk.

Margaret Atwood

It’s significant that Jean doesn’t let Vicky sleep in the spare room, which you’d think is precisely for events such as these. No, Jean doesn’t consider Vicky a legitimate ‘guest’. She doesn’t even give Vicky clean bedclothes, and makes her use the bedclothes that have already been used by Dorrie, because then Jean will only have to wash them once. Instead of a guest, Vicky becomes a surrogate daughter for a few days. Jean tries to perform motherly comfort but, ironically, Jean is as cold as she perceives Vicky to be. While performing mothering, all the while Jean betrays (to the reader) an internal monologue at odds with her gestures. She doesn’t want to touch this girl to comfort her.

In the mid 20th century, as Jackson wrote this story, it was understood that people process grief differently. (Expressions of grief are partly culturally informed.) A possible delay in trauma processing is addressed in the text, via the more empathetic voice of the doctor.

A VISIT FROM MRS WRIGHT

Why did Jackson create the character of Mrs Wright, who has turned up for a cup of tea at Jean’s house, but is clearly after salacious details of the accident?

Comically, Mrs Wright and Jean are friends for a reason. They’re very much of a type. Yet Jean judges Mrs Wright for stepping into matters that shouldn’t concern her. The visit says something about humankind: We see in others most clearly the deficiencies we possess ourselves.

Vicky uses her powers of premonition as weaponry, and tells Mrs Wright that her son will soon be expelled from medical school. The following response could be straight out of Anne Of Green Gables, said by Mrs Lynde:

“I’ll overlook it,” Mrs Wright said, “considering your present circumstances.”

“All She Said Was Yes” by Shirley Jackson

don’t go in any boats

Vicky Lanson has another premonition. She tells Jean to avoid boats. As soon as this is mentioned, we can predict Jean’s fate. Unless something happens in Jean’s house to endear her to Vicky. Perhaps Vicky will prove to Jean that she really can see into the future?

No, that doesn’t happen. At the end of the story we are left knowing that Jean is planning a cruise. It almost seems Jean has chosen a cruise on the water to spite Vicky Lanson, as if she must prove to herself that Vicky is a nutter by making it safely back to land.

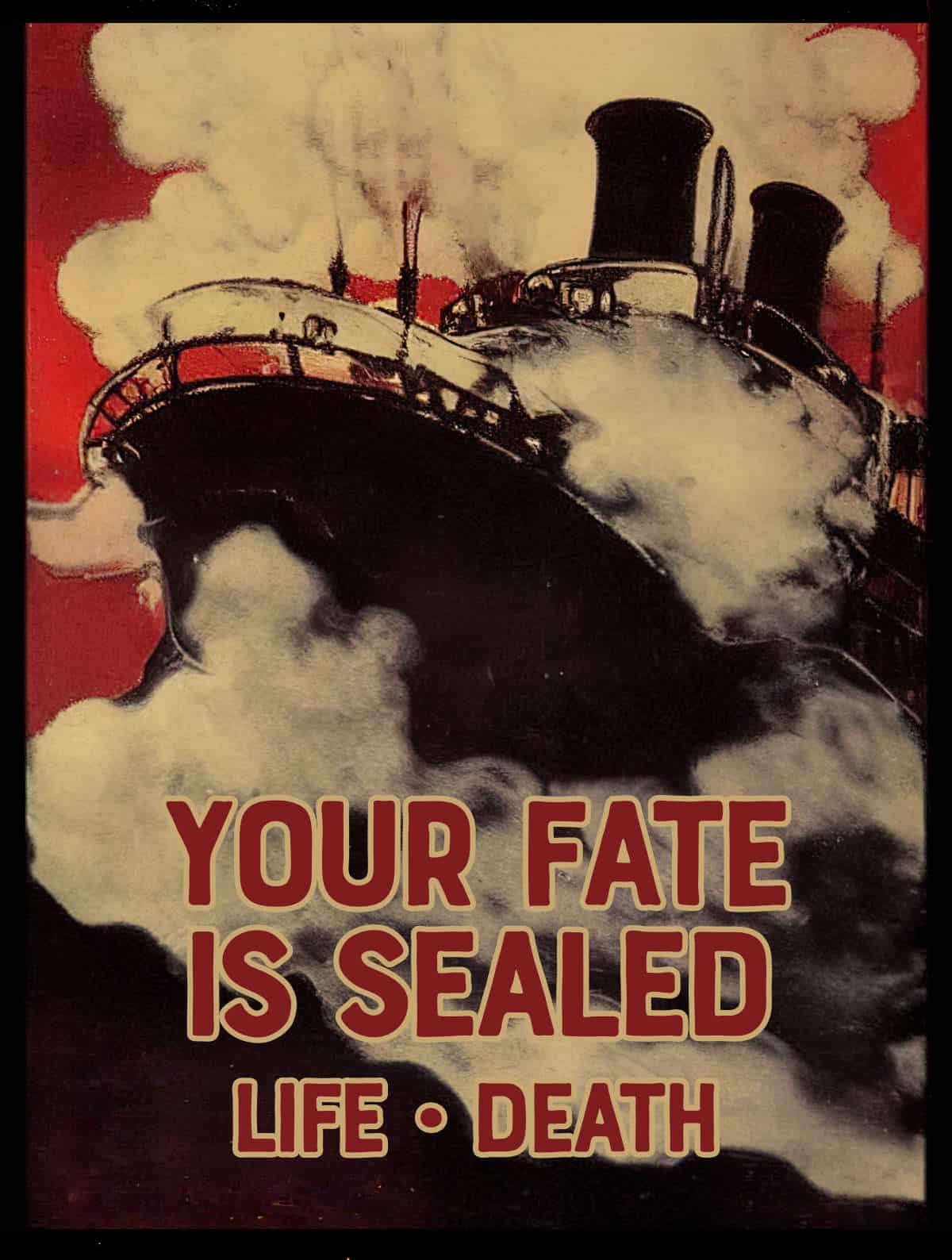

THE PARADOX OF PREDICTING THE FUTURE

The paradox of knowing the future and communicating it: Simply by knowing the future, you’ve already changed the future. Or have you? Shirley Jackson skirts around this paradox by surrounding Vicky, the contemporary Cassandra, with adults who refuse to believe her. Vicky is dismissed because she is strange. That’s the other paradox: She is strange because she is dismissed. Now that Vicky has been othered due to her supernatural abilities, every single thing she does and says is stigmatised by the judgy, busybody narrator. This short story also says something fundamental about stigma.

If someone can predict the future, does that mean the future is already ‘written in stone’? Even if Vicky warns people against boarding a cruise or driving fast round corners, do the victims possess the ability to alter their course of action? The ending of “All She Said Was Yes” suggests not. Cassandras such as Vicky are thereby doomed to knowledge without the ability to do anything about it. The worse possible combo for mental health. ‘Mental health’ is not a phrase Jackson would have seen much. She has created a teenager who has been galvanized by her ability to see the future. Nothing fazes her.

But we know that’s not how it works in reality. Perhaps Vicky is yet to learn that nothing she says will ever have any effect?

“ALL SHE SAID WAS YES” AS CLIMATE CHANGE ALLEGORY

Vicky’s combination of seeing the future play out yet not possessing the ability to do a single thing about would feel familiar to politically aware young people of today. Climate change scientists predict a grim picture for Gen Z lives, yet the Boomers who run the world are the Howards and the Dorries, and the gossiping busybody neighbours who continue to enjoy their excessive consumption (cruises) and drive their fast cars. This could serve as contemporary allegory for an older generation, many of whom refuse to accept the realities of consumption and adjust their lives accordingly.

See Helen Simpson’s short story “In-flight Entertainment” for a 2010 take on that.

Of course, few people were talking about global warming in Shirley Jackson’s lifetime. (Few, but not zero.) Climate change was certainly not Americans’ greatest concern in the mid 20th century. Nuclear instability was front and centre. “All She Said Was Yes” can be read as an outworking of anxieties around The Cold War. People understood the world could end at any moment. A few men were now in charge, now. This was brand new in the history of the world. For those of us born into a world with existing nuclear weapons, the world doesn’t seem all that unstable because we’ve never known any different, but Shirley Jackson’s generation was born into a pre-nuclear reality and had to get used to new peril: Those few men in charge could end everything for everyone tomorrow, and there’s not a darn thing the common reader can do about that.

Nothing has changed there, of course, except for a few decades of relative world peace. (My entire childhood and young adulthood. I never worried about war because we didn’t realize until recently that in 1983 a few men-in-charge came very close to blowing us all up.)

I was disappointed; the child had been amusing herself writing gossipy little paragraphs about her neighbors and her parents’ friends — although what else would you expect, considering the way Don and Helen used to talk about people? — and horror tales about atom bombs and the end of the world, not at all the kind of thing you like to think a child dwelling on

“All She Said Was Yes” by Shirley Jackson

The Doomsday Clock is a symbol that represents how close we are to destroying the world with dangerous technologies of our own making. It warns how many metaphorical “minutes to midnight” humanity has left. Set every year by the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, it is intended to warn the public and inspire action.

As of 2022, Doomsday Clock remains at 100 seconds to midnight—closest ever to apocalypse. It is updated at the start of each year. 2022 required a March update.

PREMONITIONS AND FATE

The idea that some people can see into the future continues in the (sub-)cultural imagination. If you’re a lay person like me, who has ever read pop astronomy books, you’ll understand that time is a bizarre, bizarre thing. If you can believe the many worlds theory is a distinct possibility, anything seems possible, including the idea that everything was set in motion from the moment of the Big Bang, and what seems like choice is in fact a consequence of billions of years of evolution. In that case, perhaps some people really do get glimpses into what we conceive of as ‘the future’?

Of course, it’s not at all helpful to think like this. Living a good life here on Earth in a human world with our own concept of shared time requires that we believe we have choice. Perhaps the most terrifying part of Shirley Jackson’s short story is not that two people we never meet have been killed in an accident, or that a first person narrator who we don’t even like is about to board a doomed cruise liner. Rather, it’s the notion that our fates are sealed. No matter what we do, we’re doomed.

This is, of course, true in a broader sense. We know we will die. We simply don’t know when, or how. Our fates are sealed; only the details remain unknown to us.

People have been thinking about this for thousands of years. ‘Determinism’ a.k.a. ‘causal determinism’ is the word which describes various philosophical views proposing everything that happens today has already been determined by everything in the universe that happened before.

If this is how the world works, nobody is culpable for anything, not even mass murderers. Is it ethical to imprison a mass murderer in solitary confinement for the term of their natural life if they were doomed to murder from the instant of the Big Bang?

The inverse of determinism is ‘indeterminism’, ‘nondeterminism’ or ‘randomness’. Isn’t free will another ‘inverse’ of determinism? Well, some philosophers argue that ‘free will’ and ‘determinism’ can co-exist happily.

COMPATIBILISM (ANCIENT STOICS, THIRD CENTURY BC; MEDIEVAL SCHOLASTICS)

Compatibilism is the belief that free will and determinism are mutually compatible and that it is possible to believe in both without being logically inconsistent.

Compatibilists believe that freedom can be present or absent in situations for reasons that have nothing to do with metaphysics. They say that causal determinism does not exclude the truth of possible future outcomes.

Wikipedia

CLOCKWORK UNIVERSE (the enlightenment, 1600s)

In the history of science, the clockwork universe compares the universe to a mechanical clock. It continues ticking along, as a perfect machine, with its gears governed by the laws of physics, making every aspect of the machine predictable.

Wikipedia

MECHANICAL PHILOSOPHY (THE ENLIGHTENMENT, 1600S)

This view may be people trying to reconcile their magical and supernatural beliefs with the scientific advancements in mechanics.

The mechanical philosophy is a form of natural philosophy which compares the universe to a large-scale mechanism (i.e. a machine). The mechanical philosophy is associated with the scientific revolution of early modern Europe. One of the first expositions of universal mechanism is found in the opening passages of Leviathan by Thomas Hobbes, published in 1651.

Wikipedia

LAPLACE’S DEMON (early 1800s)

In the history of science, Laplace’s demon was a notable published articulation of causal determinism on a scientific basis by Pierre-Simon Laplace in 1814. According to determinism, if someone (the demon) knows the precise location and momentum of every atom in the universe, their past and future values for any given time are entailed; they can be calculated from the laws of classical mechanics.

This idea states that “free will” is merely an illusion, and that every action previously taken, currently being taken, or that will take place was destined to happen from the instant of the big bang.

Wikipedia

All of these ideas about determinism rely on what we now call Big Data, which is inextricably bound with artificial intelligence. (AI requires massive amounts of data before it can do anything.) 2022 has been a watershed year for advances in AI, especially in art and language.