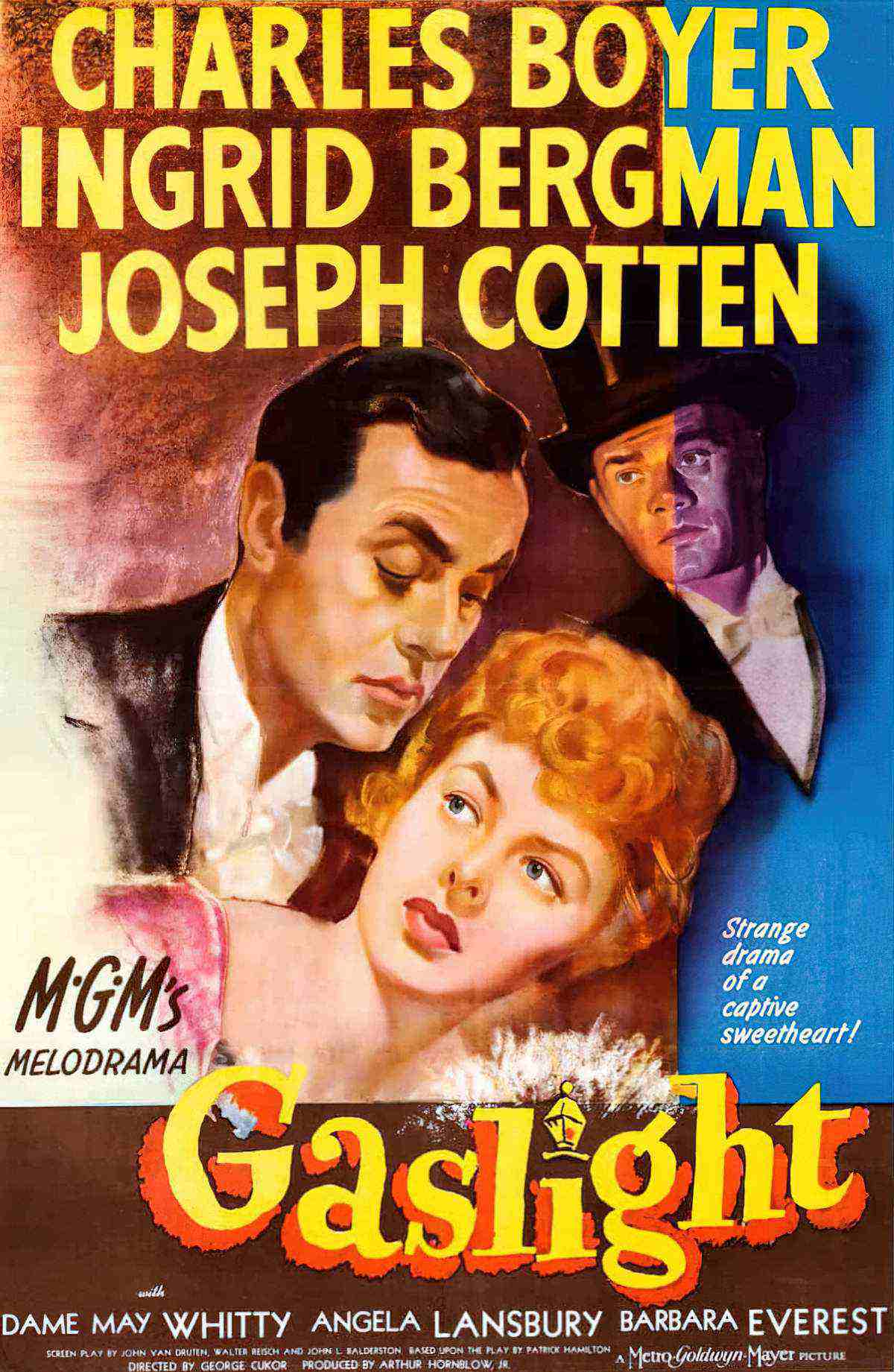

One remarkable thing about Alice Munro: her ability to see aspects of psychology which only drew public attention decades later. In “The Bear Came Over The Mountain” we have a beautiful character study of a philandering man and, his self-justification for wrong-doing and what has since been called sexual solipsism. In “Queenie” Munro paints a picture of what the authorities call ‘coercive control’, or what is known in pop-culture as ‘gaslighting’ (after the 1944 movie).

Laura Richards explains the nature of coercive control here.

SETTING OF “QUEENIE”

Canada, 1960s. The Byrds are popular. “Turn Turn Turn” (which uses words from the Bible) gets a mention in the story, to set the musical scene.

Chrissy follows Queenie to the Greek populated part of Toronto, which I believe is called Danforth. I can’t find any locals on the Internet who have geolocated this story, but I’m imagining Queenie worked someone like this.

NARRATION OF “QUEENIE”

In narrative terms, Alice Munro uses Chrissy in an unusual but seamless way. I’m only noticing because I’m looking for this, but she brings Chrissy back into the story whenever Queenie needs a diegetic narratee.

Here’s an example of the switch from plain ole third person narration to Queenie confiding in Chrissy. Notice how Munro doesn’t make Chrissy walk in through the door, sit down for a cup of tea — these conversations are suspended in space. Yet they work:

She found it, and she threw it all out. She never told Stan.

[THIRD PERSON NARRATION] That this was the ideal place. And then she forgot. She was a little drunk – she had to be. She had forgotten absolutely. And there it was.

[SWITCH TO USING CHRISSY AS THE OTHERWISE INVISIBLE NARRATEE] ‘I pitched it,’ she said. ‘It was just as good as ever and all that expensive fruit and stuff in it but there was no way I wanted to get that subject brought up again. So I just pitched it out.’

Chrissy is an extradiegetic narrator because a long time has elapsed since she was a part of this story, to the point where her younger self feels to her like a different person. We only get a sense of how much time has elapsed near the end:

Even I could see that, inexperienced as I was.

SYMBOLISM OF NAMES

A short while ago I analysed a wonderful film called The Wrestler and talked about the importance of names — names stand in for our identities, so when we get a new name we have a new identity. When “Queenie” opens with a paragraph about a new name, we know this is going to work similarly, and it does:

“It was more of a surprise to me to hear her say ‘Stan’ than it was to have her let me know she wasn’t Queenie anymore, she was Lena. But I could hardly have expected that she would still be calling her husband Mr. Vorguilla after a year and a half of marriage. During that time I hadn’t seen her, and when I’d caught sight of her a moment ago, in the group of people waiting in the station, I almost hadn’t recognized her.”

The rest of the story exposes the real reason why Stan insists on using Queenie’s birth name — he is a coercively controlling individual who is taking charge of Queenie in her entirety, replacing her with someone who would like to mould for himself, like a regular Pygmalion.

Chrissy’s feeling towards ‘Stan’ (rather than Mr Vorguilla) indicates how different he seems to her now that she sees a new side. He might as well be a different person entirely.

“I still couldn’t get used to her saying ‘Stan.’ It wasn’t just the reminder of her intimacy with Mr. Vorguilla. It was that, of course. But it was also the feeling it gave, that she had made him up from scratch. A new person. Stan. As if there had never been a Mr. Vorguilla that we had known together—let alone a Mrs. Vorguilla—in the first place.”

QUEENIE, STAN VORGUILLA AND COERCIVE CONTROL

This short story makes an excellent case study in how coercively controlling relationships tend to work. “Queenie” should be required reading for all young women, in particular.

- Queenie is first set up as an empathic character who with a high emotional quotient. She comforts her mother when the mother has bad dreams. Despite being no good at sport, nor academically, she is the first picked for teams and projects at school. Subverting the fairy tale expectation that step-sisters naturally fight, Chrissy and Queenie never fight. In other words, Queenie is the perfect victim for a coercively controlling older man. She has been rewarded her entire life for pleasing others and performing emotional labour. And for a girl of this era who is not academically inclined, she believes—as many really did—that her only route to success is to find a husband as quickly as possible and perform emotional labour for him.

- Queenie has absorbed a set of related culturally dominant relationship tropes which are wholly unhelpful to her in this situation: That men are not ‘normal’ (because men and women are a fundamentally different binary, in constant opposition); that jealously is only natural and that if only a woman can sufficiently please a man (with her grooming, with her care and attention) then he will eventually treat her well. In contrast, Chrissy has not absorbed these messages yet we see the older ‘wiser’ Queenie school her younger step-sister, meaning to help, but exposing her own shortcoming: She is wrong.

- Queenie puts a lot of effort into dressing in a hyper-feminine way. Though she is at ‘home’, she wears a skimpy dress, full make-up and lots of jewelry. (Munro paints the picture of a so-called ‘mod‘.) In this era especially, women were overtly encouraged to look good for their husbands at all times, otherwise risk losing them. This cultural message was exploited by advertisers.

- Coercively controlling people don’t need to be violent often, or at all. They only need to exude the impression that they could be violent at any moment. Stan doesn’t like the sound of the kettle, so Queenie goes to pains to keep him from hearing it while it’s on. These petty preferences are clearly a form of control.

- Stan goes through Queenie’s private belongings, checking up on her e.g. her purse. He controls every aspect of her life, and continues to do so obsessively, sending Chrissy Christmas cards hoping to reconnect with Queenie long after she has escaped.

STORY STRUCTURE OF “QUEENIE”

A one-star review of “Queenie” on Goodreads makes a good job of describing the surface level plot:

This was a completely boring story of a young girl who shacks up with her pervy music teacher, runs off with him, finds out he is horrible then runs out on him. Her sister never hears from her again.

From a four-star review:

This was the first time I had read Alice Munro and boy does she pack a punch! She crams an entire lifetime into 62 pages.

Yes, that is exactly what Alice Munro tends to do. ‘Lifetime in miniature’ is Alice Munro in a nutshell.

Someone at Summary Brew makes the mistake of calling this story ‘lightweight’. I see nothing lightweight about the topic of coercive control:

In this lightweight short story, our protagonist shares her childhood memories with her stepsister – Lena, affectionately referred to as “Queenie”.

SHORTCOMING

Who is the ‘main character’ of this story? Chrissy is clearly the less interesting character and is therefore used as the viewpoint — bridge between audiencea and Queenie. One Goodreads reviewer says, “The narrator, Chrissy, seemed to me a well-constructed expedient to depict Queenie’s character in an in-depth and detailed way.” (I like that use of the word ‘expedient’.)

One really useful question writers can ask when drawing a character is: What is my main character wrong about at the beginning of the story? And how much will they change by the end? If a character starts out wrong and continues wrongheadedly into the future, then you are writing a tragedy. As I described above, Queenie is wrong about how good relationships really work.

“Well, of course he was wrong. Men are not normal, Chrissy. That’s one thing you’ll learn…”

Alice Munro uses the technique of giving Queenie a catchphrase which sums up her worldview. Chrissy tells us this is something we might well see on a movie poster:

DESIRE

Queenie believes that her life won’t begin until she finds a man, so she finds one as quickly as possible.

OPPONENT

Queenie’s ‘romantic’ opponent is of course Stan.

Chrissy is also her opponent for holding a different world view.

‘Well you and me are very different, Chrissy. Very different’. She sighed. She said, ‘I am a creature of love.’

But for the majority of the story, Chrissy doesn’t challenge Queenie.

PLAN

This is an interesting example of a story in which the plan of the ‘main character’ (I mean Chrissie) runs alongside what the reader might wish the plan to be.

For this reader, I wish Chrissie would take Queenie by the shoulders and give her a good talking to. In most films, and in many popular written stories, you will encounter a scene in which the ally confronts the main character: “What are you doing?! Don’t you know this is dangerous?!” That kind of thing.

But Alice Munro never gives us that moment. Instead, we don’t even know why Chrissy has gone to live with Queenie in Greektown. At first I thought she’d gone as Queenie’s rescuer, but Chrissie is just as naive as Queenie is at that point in their lives. She looks up to her older married step-sister and that’s just how it would’ve been. Anything else would have been unrealistic.

BIG STRUGGLE

The would have been a long big struggle and a culmination for Queenie, which led to her leaving Stan. But we don’t see that.

The battle scene for Chrissy happens over the scene where Queenie is trying to silently and hurriedly make tea. I have previously written about the problem of ‘tea-drinking scenes’ and how writers can sometimes rely upon them too heavily because we desperately want to give our beloved characters a well-deserved break. But in “Queenie”, Alice Munro shows us that tea scenes — specifically kitchen scenes — can be chock full of tension, and constitute Battle scenes in themselves.

ANAGNORISIS

Chrissie realises who Stan is before Queenie does. Alice Munro describes the moment she has this revelation without telling the reader what that revelation is:

I couldn’t think. I still had the sensation of the room moving around me, though it wasn’t doing that any more in a physical way.

Half a page later we are told she’s had her Anagnorisis:

It could also have been that he sensed a change in me. People do sense the difference, when you are not afraid of them any more. He would not be sure of this difference and he would have no idea how it came about, but it would puzzle him and make him more careful.

And in case the reader still isn’t clear on exactly who these men are, we are shown an overt example of their misogyny:

‘You’d think the husband might have come forward,’ said Leslie. ‘If he was the druggist, he was the boss.’

‘He ought to brew up a special dose,’ Mr Vorguilla said. ‘For his wife.’

Via Chrissy’s narration, Alice Munro puts into words why she has included all of these relationships — for a compare and contrast exercise for the reader, who is hopefully considering what they want in a relationship (if anything at all):

My father and Bet. Mr and Mrs Vorguilla. Queenie and Mr Vorguilla. Even Queenie and Andrew. These were couples and each of them, however disjointed, had now or in memory a private burrow with its own heat and confusion, from which I was cut off. And I had to be, I wished to be, cut off, for there was nothing I could see in their lives to instruct me or encourage me.

Chrissy’s anagnorisis is completed when she goes out with Leslie. And this is the part which showcases Alice Munro’s talents. The epiphanies she gives her characters are hard-won, unexpected (in this case coming from an unexpected source — Leslie is himself a different kind of misogynist), subtle and complex.

I would have seen flaws in this, later in my life. I would have felt the impatience, even suspicion, a woman can feel towards a man who lacks a motive. Who has only friendship to offer and offers that so easily and bountifully that even if it is rejected he can move along as buoyantly as ever. Here was no solitary fellow hoping to hook up with a girl. Even I could see that, inexperienced as I was. Just a person who took comfort in the moment and in a sort of reasonable façade of life.

His company was just what I needed at the moment, though I hardly realised it. Probably he was being deliberately kind to me. As I had thought of myself being kind to Mr Vorguilla, or at least protecting him, so unexpectedly, a little while before.

NEW SITUATION

When the story is nearly over it shifts abruptly in time and we are told more clearly that this is a memory, long-since passed.

I was at Teachers’ College when Queenie ran away again. I got the news in a letter from my father. He said that he did not know just how or when it happened…

Alice Munro uses the technique of sideshadowing to allow the reader (via Chrissy’s imaginings) to imagine what might have happened to Queenie:

But now something has happened. Now in the years when my children are grown up and my husband has retired, and he and I are travelling a lot, I have an idea that sometimes I see Queenie. It’s not through any particular wish or effort that I see her, and it’s not as if I believed it was really her, either.

Once it was in a crowded airport, and she was wearing a sarong and a flower-trimmed straw hat. Tanned and excited, rich-looking, surrounded by friends. And once she was among the women at a church door waiting for a glimpse of the wedding party. She wore a spotty suede jacket that time, and she did not look either prosperous or well. Another time she was stopped at a crosswalk, leading a string of nursery-school children on their way to the swimming-pool or the park. It was a hot day and her thick middle-aged figure was frankly and comfortably on view, in flowered shorts and a sloganed T-shirt.

Notice how the paragraph above makes use of the Rule of Three in Storytelling. Now we have the main sideshadow:

The last and the strangest time was in a supermarket in Twin Falls, Idaho. I came around a corner carrying the few things I had collected for a picnic lunch, and there was an old woman leaning on her shopping-cart, as if waiting for me. A little wrinkled woman with a crooked mouth and an unhealthy-looking brownish skin. Hair in yellow-brown bristles, purple pants hitched up over the small mound of her stomach – she was one of those thin women who have nevertheless, with age, lost the convenience of a waistline. The pants could have come from some thrift shop and so could the gaily coloured but matted and shrunken sweater buttoned over a chest no bigger than a ten-year-old’s.

The shopping-cart was empty. She was not even carrying a purse.

Unlike those other women, this one seemed to know that she was Queenie. She smiled at me with such merriment of recognition, and such a yearning to be recognised, that you would think this was a moment granted to her when she was let out of the shadows for one day in a thousand.

And all I did was stretch my mouth at her, as at a loony stranger, and keep on going towards the check-out.

Chrissy goes back to find her, only to her already gone.

It was possible but hardly likely that she was still in the store, and that we kept going up and down the aisles just missing each other.

What is the emotional effect of this ending? For me it’s sorrow and regret. We cross paths with people and never see them again. Sometimes we share a part of our lives with people, then never see them again. I think this was more common before social media allowed the possibility of (faux-) reconnection with people from our pasts, but in the pre-Internet world in which Alice Munro is writing, you really can lose someone forever.

From a five-star review on Goodreads:

This wonderful story reminds us that, at a certain point, we no longer look to the future hoping for excitement or novelty as often as we look into the past for comfort and reassurance, or, if we are honest, with regret. Alice Munro’s ‘Queenie’ once read, ripples through our minds, reminding us of those times, gone forever, that mean the world to us.

FURTHER READING

How Brainwashing Works from How Stuff Works

Everybody must read See What You Made Me Do by Jess Hill, pronto. (Except if you have firsthand experience of partner violence, in which case you get a pass.)