Alexander and the Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Day is an American picture book written by Judith Viorst, published 1972.

This was the first in the Alexander series, followed by:

- Alexander, Who Used to be Rich Last Sunday

- Alexander, Who Is Not (Do You Hear Me? I Mean It!) Going to Move

- Alexander, Who’s Trying His Best to Be the Best Boy Ever

Writer, journalist and psychoanalyst Judith Vorst wrote her Alexander books modelled on her own three sons, who were about that age when she wrote them. She decided to write the book about Alex because he seemed to have more than his fair share of bad days at the time. At first he wasn’t happy about this and asked if someone else could have the Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Day, but when his mother reminded him that he’d get his name in big letters on the cover, he agreed to be the star. These days he is apparently quite happy about the whole thing.

“Practically every everything that I’ve written that is funny or joyful, I’ve probably lived through first with tears — and crying and bitching and moaning and carrying on,” she says. “I mean, I am not your merry little lady bouncing chucklingly through life. But eventually I pull myself together.

Judith Viorst, at the age of 88

Much more recently, Viorst has created a girl version of Alexander. Her name is Lulu.

- Lulu and the Brontosaurus

- Lulu Walks the Dogs

- Lulu’s Mysterious Mission

Like Alexander, Lulu is what Viorst describes as ‘a hard like’. These are the Max’s from Maurice Sendak’s Wild Things, or some of Shel Silverstein’s characters. Viorst names The Secret Garden as an influence from her own childhood. The children in that classic are also hard to like. Viorst writes these characters because she knows children take comfort in learning that others have the same bad feelings as they do.

(Separately, I believe girl characters are judged more harshly than boy characters for the exact same behaviours, which mirrors a real world phenomenon in which girls are expected to be more polite/giving/deferential than boys, who are expected to be strong, confident leaders.)

Before writing Alexander, Viorst had worked as a children’s book editor. This partly explains how she was able to create such an iconic book that the title became part of the English language lexicon. (She says she is very proud of this fact.) Like all the best picture books, Alexander feels simple. For this reason, it’s worth breaking down.

STORY STRUCTURE OF ALEXANDER AND THE TERRIBLE, HORRIBLE, NO GOOD, VERY BAD DAY

Alexander and the Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Day feels like a picturebook ahead of its time. Aside from the details, which are from early 1970s America, this story could easily have been published last year. What makes it feel so modern?

First, the reader is launched straight into the story with zero preamble. What exactly does that mean, though? More traditional picture books start out with what some have called the ‘iterative’ and then switch at some point to the ‘singulative’. You’ll know a story like this because it goes something like:

[ITERATIVE] Once there was a little boy called Alexander who lived with his two older brothers in his house. Alexander loved desserts and new shoes and visiting his father at work. [SINGULATIVE] One day, Alexander got up and…

Second, Alexander and the Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Day is written in first person. First person point-of-view is still an unusual choice for picture books, and marks it out as different. More lately we have authors like Jon Klassen writing in a sort of confessional tone, in first person. See: This Is Not My Hat.

Mo Willems writes mini plays which are entirely dialogue, which aren’t exactly first person, but his book titles are: e.g. I Am A Frog.

Third, it took a while for the gatekeepers of children’s literature to come around to the idea that picture books don’t have to model good behaviour. Even now, you can look up customer reviews on award winning stories such as This Is Not My Hat and see people who refuse to let their children read the book because they don’t want fictional bad behaviour to go unpunished, on the assumption that all characters who appear in books are role modelling directly. Alexander is not a role model character, and therefore feels part of the modern corpus.

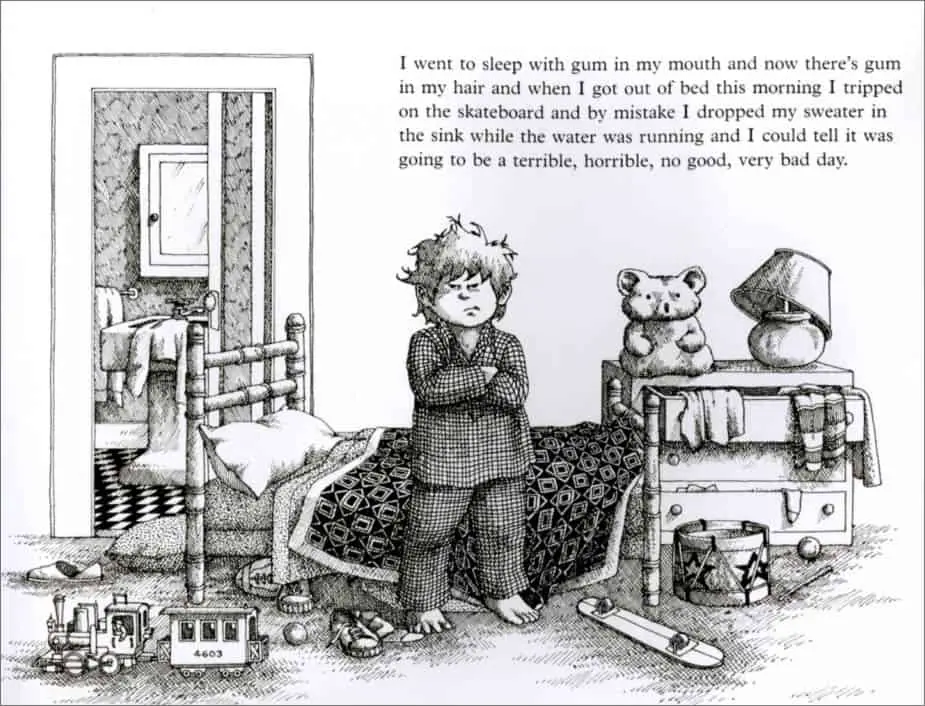

Also, the text is written in free indirect style, without heed to traditionally correct grammar. This is conversational grammar, with plenty of conjunctions, without thought to the listener. Alexander and the Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Day is masterfully composed and great fun to read.

SHORTCOMING

Alexander’s shortcoming is that he is prone to bad moods. Some of these moods are completely self-generated. It was Alexander who left the skateboard beside the bed, and Alexander who fell asleep with chewing gum in his mouth. (Is it just my modern sensibilities or does every parent think, He might have choked!)

DESIRE

In all works of fiction—and probably nonfiction, too—there are essentially two plots, Plot A and Plot B.

With Plot A, a character’s status-quo condition of discontent is challenged when opportunity presents itself .

With Plot B, a character’s status-quo condition of contentment meets with an obstacle or irritant.

Peter Selgin

What would you call Alexander and the Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Day? This story fits never Plot A nor Plot B. Alexander’s status-quo condition is of discontent but opportunity does not present itself.

What does Alexander want? My first thought is, “Well, obviously he wants to have a good day. Or, a better day than he’s having.” But does he really? Is he not revelling in his bad day, especially by the end of it?

We can certainly say that in any given scenario Alexander wants a certain thing from that scenario:

- He wants a toy out of his cereal

- He wants a prime spot in the car ride to school

- He wants his teacher to be impressed at his attempt at a joke — showing her a blank piece of paper intended to be an invisible castle

- He wants to impress her with loud singing

- He wants to be included in his best friend’s games. (This is a rare example of relational aggression involving boys in children’s literature.)

- He wants to execute revenge on his best friend

- He wants dessert

- and so on

This story is also about what he does NOT want:

- Does not want to go back to the dentist for a filling

- Does not want to get in trouble for fighting

- Does not want beans for dinner or TV shows with kissing

- and so on

The splintered desires with no overriding ‘desire line‘ make this book function as a series of funny vignettes. But this story does achieve strong narrative drive because we want to see what terrible thing will happen to Alexander next. We want to see how he’ll react when he doesn’t (or does) get what he wants.

OPPONENT

Masterfully, Viorst uses external irritations as well as self-generated irritations. By the end of the day, Alexander has slipped so far into his bad-day mindset that he even hates the pattern on his pyjamas, for no good reason that we can see.

Since Alexander’s day takes place in a number of different settings, starting and ending in his bedroom, Alexander and the Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Day is written with a mythic structure. A character goes on a journey, meets various opponents along the way and returns home a changed person.

PLAN

Here’s the masterful part of the story, which shows how well Viorst understands story structure: “I think I’ll move to Timbuktu.” (I have seen this story read online with “I think I’ll move to Australia. This wouldn’t work for those of us here in Australia. Did we get Timbuktu instead, for Australian editions?)

I can imagine coming up with an idea for a story very similar to this one, even finding the voice. But if something were missing it might be this part. I find picture books are like that. Most often I write first drafts and something is missing. The refrain about moving to Timbuktu is an ‘eye of the duck’ part of this story.

(Eye of the duck is a David Lynch term which basically means ‘the part of the story which really sets it off’.)

Timbuktu is one of those details which dates the book charmingly. This used to be the place which is nowhere from my own childhood. I believe I got it from a Mr Men book, but I may have false memory there. I didn’t think it was a real place. I thought it was entirely fictional. (It’s an ancient city situated smack bang in the middle of Mali, a country in Northern Africa.) Unfortunately, the Google street car has not yet made it to Timbuktu, and you can’t take a virtual walk around the streets.

BIG STRUGGLE

Each scenario in Alexander’s day has its own minor big struggle, but these small big struggles increase in intensity as the day wears on, culminating in a physical on-the-ground incident in which Alexander ends up sitting in a muddy puddle. That’s not the last big struggle, but it is the most visual one. After that, the big struggles are directed inward.

ANAGNORISIS

The satirical nature of this mythic journey rests on the fact that Alexander is just as cranky at the end of the day as he was at the beginning. Some days are just like that, his mother reassures him. This is a consolation rather than a revelation.

How else could this have ended? Some authors would not have trusted the negative emotionality of this story and something nice would have happened to Alexander right before bedtime to reassure him that good things happen, too. Perhaps his mother sat down with him, just him, to read a bedtime story, or perhaps those railroad pyjamas were actually his favourite, and this cheered him up. But Judith Viorst — who has a background in psychoanalysis — understood that this emotion needed to continue without a token offset.

NEW SITUATION

It’s likely Alexander will wake up in a better mood tomorrow, but there will also be more days similar to this one.

SEE ALSO

Fuse8 (Betsy Bird) n’Kate talk about this picture book on their podcast in episode 40.

The Terrible Suitcase by Emma Allen is similar to Viorst’s book in many ways but stars a girl and is a little more dreamy in tone.

Another is My No No No Day! by Rebecca Patterson, also starring a girl.

Using Alexander to teach philosophy in the classroom (aesthetics and metaphysics)