Kristen Roupenian joins Deborah Treisman to read and discuss “Afternoon in Linen,” by Shirley Jackson, which appeared in a 1943 issue of the New Yorker magazine. I count this story as a perfect example of the dark carnivalesque, in the same way The Chocolate War by Robert Cormier is darkly carnivalesque. Unlike a picture book for young readers, in which a cat in a hat appears and everyone has fun for a while, these older characters of the dark carnivalesque subgenre have fun playing with each other in a bid for power and respect, however small the stage.

Below are my own thoughts building on notes taken from the converation between Roupenian and Treisman.

SETTING OF AFTERNOON IN LINEN

Note that Jackson has given us a soundtrack to this story. Howard is playing “Humoresque” on the piano. Here’s an orchestral version:

And here it is played on a piano. I don’t imagine Howard’s was nearly as smooth as this, though. Let’s imagine this, but comically grating and stilted.

PERIOD — This story was written in 1942 and published in 1943, so it’s fair to say Shirley Jackson had the idea for this story bubbling away in the midst of a world war.

DURATION — 5-10 minutes or so. The entire story is a single scene (sans flashbacks, backstory etc.) so however long it took you to read the dialogue, that’s about how long it would take to play out in real life.

The fancy term is ‘isochronical’. A story is isochronical if the timespan of the story and the time it takes to read the story (the ‘discourse timespan’) are the same.

LOCATION — in some white suburb of America, I imagine

ARENA — a grandmother’s formal living room

MANMADE SPACES — We are given no detail of the outside world.

TECHNOLOGY CRUCIAL TO THIS PARTICULAR STORY — There is no technology crucial to the story unless we count the piano, but it’s interesting to consider the ‘technology’ in the older story to which this short story alludes.

Through The Looking Glass (1871) is the sequel to Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll. The sequel is also a portal fantasy but instead of falling into a rabbit hole Alice goes through a mirror. In this fantasy world everything is reversed, but not just in a reflected way, also in a logic way. (Running helps you remain stationary, walking away from something brings you towards it, chessmen are alive, nursery rhyme characters exist etc.).

This leads me to reversals more generally. The word ‘camp‘ comes in handy when describing the humorous aspect of “Afternoon In Linen”.

Camp is notoriously hard to define, but in most conceptions it involves both a sense of doubleness — things are not merely what they seem to the naive viewer — and a preference for reversal — the very bad now reinterpreted as good. It is a way of understanding or interpreting the world. Historically, camp emerges in gay subculture where it functions as a kind of passive resistance to the straight world.

A carnivalesque story is all about flipping hierarchy. Adults disappear, children are now in charge. In stories aimed at a young audience, the adults will return at the end, having allowed the children a short period of unsupervised fun. This is reassuring. But in a carnivalesque story for adults, the flipping can feel out of control from the start, and ends with no reassurance that some kind of order has been restored.

In “Afternoon In Linen”, Shirley Jackson flips hierarchy in an interesting way. Normally we associate performative tea-parties with children.

But Jackson writes:

Although Mrs. Lennon and Mrs. Kator lived on the same block and saw each other every day, this was a formal call, and so they were drinking tea.

“Afternoon In Linen”

With this sentence, the performative aspect of adult tea-parties becomes the emphasis. Children (sweet little girls) might play tea parties, but what are adults doing? Exactly the same, really, except with real hot tea and real cakes (not mud ones, if my own childhood is anything to go by).

LEVEL OF CONFLICT — This refers to a story’s position on the hierarchy of human struggles. I wouldn’t go so far as to call this short story a war allegory, but the juxtaposition is interesting. Outside the house, patriarchal world leaders are playing games with people’s lives.

THE EMOTIONAL LANDSCAPE — This refers to the land which lives inside the main character. The imaginative landscape, the difference between what is real in the veridical world of the story and how a character perceives it — never exactly as it is, but rather influenced by their own preconceptions, biases, desires and personal histories.

It’s fascinating to consider what Harriet is thinking. I’ll go into that below.

STORY STRUCTURE OF AFTERNOON IN LINEN

PARATEXT

EPITEXT

Here’s a harsh assessment of Harriet which some readers may bring to the page:

a savage snapshot of the gleeful cruelty of which children are capable

A Rather Haunted Life author, Ruth Franklin (Shirley Jackson biography)

PERITEXT

“Afternoon In Linen” sounds like the title of a still life painting — something tame and unchallenging. Maybe a woman wearing linen, drinking tea next to a windowsill with a pot of flowers on it or something. In this vein, Shirley Jackson opens the story, as if this story were a description of a painting. There’s a ten dollar word which describes stories which are descriptions of paintings: ekphrasis. The story opens in pseudo-ekphrastic manner, with emphasis on the colour of items and clothing.

As the reader eventually learns, the story is unsettling. The cosy title is ironic.

SHORTCOMING

Is there anything more irritating than having someone mouth something about you to others in the room, assuming you don’t notice?

Why yes, it is when they mouth “shy” as the incorrect, coverall explanation for behaviour they do not take the time to truly understand.

Too many serious wounds are carelessly written off as “nothing but shyness.

Clarissa Pinkola Estés, Women Who Run With the Wolves: Myths and Stories of the Wild Woman Archetype

Worse, when an adult labels a child shy, they aren’t just commenting on the behaviour or mood of the moment, they are passing judgement on your entire character. They are actively determining who you are, and how you are perceived in the world.

Mrs. Lennon looked at Mrs. Kator and shrugged. Mrs. Kator nodded, mouthing “Shy,” and turned to look proudly at Howard.

“Afternoon In Linen”

I feel Harriet’s irritation to my core, as a former child who was often subjected to the “Shy” treatment. Later I knew a woman — my mother’s friend with a much younger daughter — who would never let anyone call her daughter “shy”.

“She’s not shy.” The mother would correct anyone who suggested it. “She just doesn’t know you.”

One day she explained her philosophy to teenage me, perhaps understanding that I, too, had been on the receiving end of “She’s just shy” for my entire life. She said that if children keep hearing they’re shy throughout their whole childhood, they’ll end up believing it, and will behave accordingly.

That little girl is an adult now, and her mother’s attitude was new for its time.

“Shy” is a word most often directed at girls. (My brothers were as laconic than I was but I never heard them called “shy”.) I suspect (hope) kids today don’t hear it nearly as often as girls of previous generations did. I mean, it was constant. On the one hand, you’re prewarned to “behave” and “be polite” and “if there are cakes, take only two.” In order to learn the lay of the land in new company, it is inevitable that well-intentioned children look and listen before they speak. Then, while you’re in this mode, there will usually be an adult who asks how old you are, what your teacher’s name is, and do you like school (always yes/no questions) and because you answer with yeses and noes, without elaboration, the adult will run out of quesions, look awkwardly at your parents (they tried, after all) and one of the adults will inevitably switch back to adult conversation with, “She’s just shy.”

Ugh!

Anyway, Harriet has my full sympathy. I haven’t read Shirley Jackson’s biography but I’m keen to know if Shirley was a “shy” little emo kid.

Back to “Afternoon In Linen” I do believe the “shy” comment is the inciting incident. Harriet decides she’s gonna destroy the joint.

Harriet is a character archetype I enjoy seeing across various stories. I know little about the girl below, but I like to think Harriet regards her grandmother with the same dark brow.

I want to know more about the girl below. I should read Crooked House. Iconic Agatha Christie cover artist Tom Addams based her on the girl from an Edward Gorey illustration.

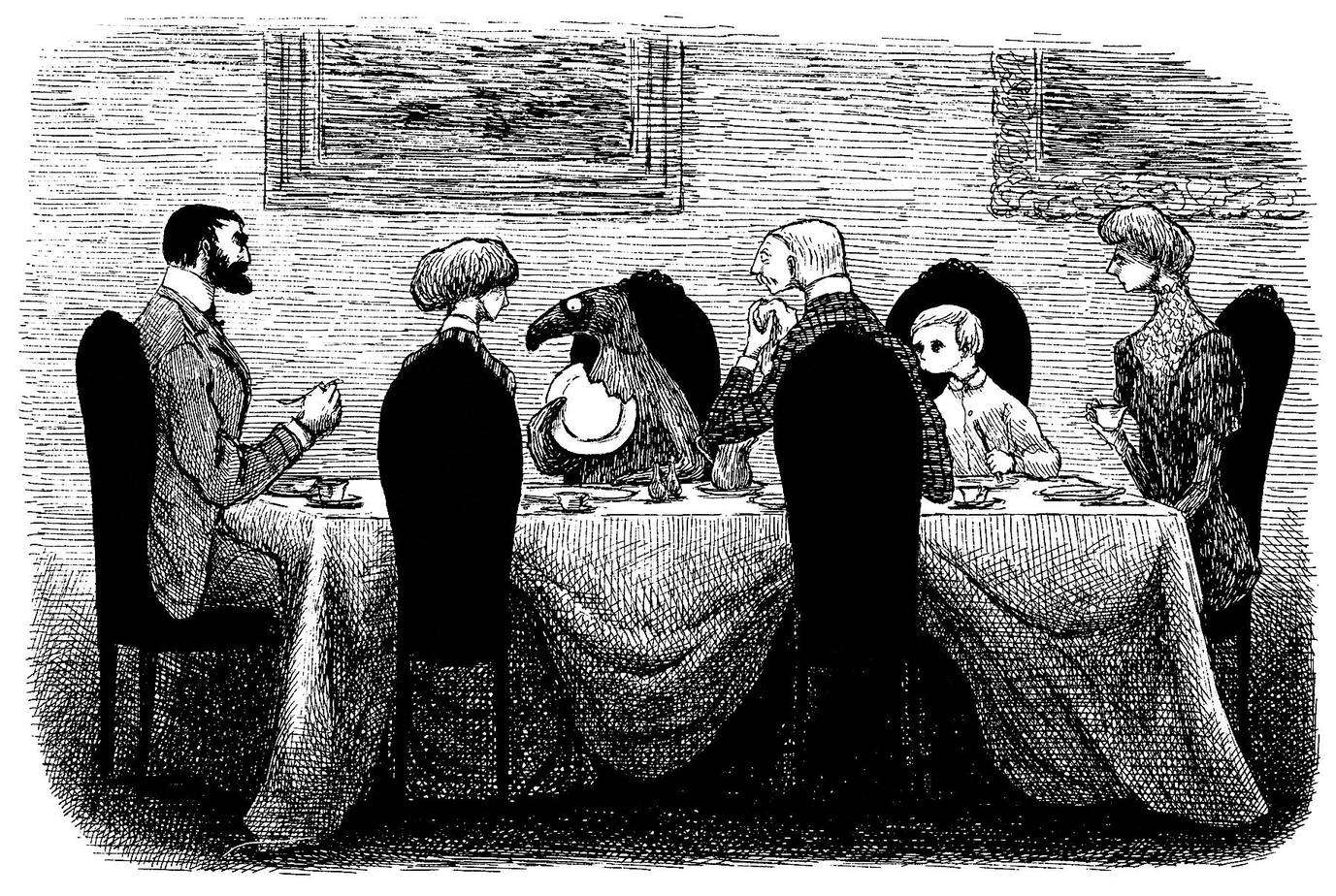

Speaking of which, I put it to you that Edward Gorey girls are all Harriet types. We’d call them emo now. Via his illustrations, Edward Gorey had this in common with Shirley Jackson: He liked to insert anarchy into prescribed, high-stakes social situations such as dinner- and tea-parties.

Personally, I like to think of Harriet as a trans or non-binary icon. “I’m a gentleman all dressed in pink paper, she thought.” At the least, Harriet has inverted gender as her first reversal of the story.

DESIRE

I believe Harriet’s deep desire is no different from anyone else’s: To Be Taken Seriously.

The masterful thing about “Afternoon In Linen”: Harriet goes about earning respect in an unexpected way. Like me, did you sort of think (hope?) that Harriet was going to sit at the piano and play magnificently? To take a Doylist view, that’d be a boring story, wouldn’t it.

So many stories feature main characters who seem to know what they want. Sure, they don’t know at the beginning. At the beginnings of stories, character are very often mucking about in their day-to-day life until something extraordinary happens to throw them into disequilibrium. At this point, fictional characters (even hapless ones) seem to recognise what they want, make plans and go about fixing things.

This doesn’t reflect reality. It especially does not reflect reality for ten-year-olds, who are typically even less able than adults to recognise difficult feelings, label them, and set about making themselves feel better. Instead, they suffer entire afternoons in what adults call “sulking”.

OPPONENT

After mouthing behind Harriet’s back and calling creating the narrative that Harriet is “shy”, the grandmother heaps insult upon insult by saying, “Harriet dear,” she said, “even if we don’t want to play our little tunes, I think we ought to tell Mrs. Kator that music is not our forte.”

But Harriet knows that music is her forte. She knows she’s better than Howard. This is another part of her own narrative that she doesn’t want crafted for her by anybody else.

IN-GROUP AND OUT-GROUP CULTURES

This is the sort of interaction which differs hugely between cultures. I first encountered it in high school with my Chinese friends: I’d go to their house and the friend’s parent, brought up in China, or Taiwan, or Hong Kong, would welcome me by giving me a compliment then following it up with something disparaging about her own child. I was particularly confronted by the Chinese father and daughter who moved in next door. He looked me up and down and told my father, “Your daughter is nice and slim! Not like my daughter, she is so fat!”

The daughter was not fat, in case you’re wondering. The father had been a doctor in China, in case you’re wondering. I was disgusted that a father would say that.

Japan shares this aspect of culture and when I was an exchange student to Japan, I learned the Japanese words to describe “in-group” and “out-group”. When Asian parents seem to disparage their own children, the dynamic is working a bit differently from how it works in the West. They are pulling their children in close. “This child is so much a part of me that they might as well be me.”

In contrast, I’m sure Asian parents think Western parents are always showing off about our damn kids. A Chinese mother recently told me her son was “terrible at maths”. Since the mother is a statistician, the son in in top maths at a private school and gets tutored, I doubted any truth to that. I turned to the Chinese-Australian son and said, “Chinese mums, eh? Always with the humility.” He laughed. Fortunately, so did his mum. I didn’t want them to think I actually believed he was no good at maths.

But because the West doesn’t have this exact dynamic going on, kids don’t always accept fake humility from their parents and grandparents. This particular tea party is a very good depiction of how Western grandparents (even more than parents) are in contrast constantly bragging about their grandchildren, mostly while attempting to disguise it.

It’s actually exhausting. And no one buys it, either!

Mrs Lennon is clearly very proud of her granddaughter, but the granddaughter knows that ‘love’ and ‘pride’ are two different things. Sure, it’s nice when your grandmother is also proud of you, but it is far more important to be understood, and loved regardless of your accomplishments. Harriet understands she is being used as a pawn in this particular scenario. She might as well be an automated organ. Following on, she might as well be reciting crappy poems out of some kitsch collection of the damn things…

To make matters worse, the grandmother says, “Play one of your own little tunes.”

The word “little” may be intended to be a humble-brag directed at Howard’s grandmother, but it is also a diminishing word. Harriet knows she is good at piano. She knows her tunes are not “little”.

PLAN

When Harriet says “I don’t know any,” I believe she is saying, “I don’t know any little tunes. Sure I know tunes, but my tunes may not be described as little.”

She’s now fallen into this painful mood and any further cajoling will have the exact opposite effect. “Plan” isn’t the word here.

I think the word “petulance” or “defiance” would be used to describe Harriet, except she has my complete sympathy.

Fuck you, Granny. That’s the entire plan.

THE BIG STRUGGLE

In this short story, many contests happen simultaneously:

- Two grandmothers compete to see who has the more accomplished grandchild

- Howard and Harriet compete to see who will end up with more social capital later, among peers

- Harriet and her grandmother compete for control of the afternoon tea arena

I’ve noticed previously that the most interesting lyrical short stories feature characters whose actions and emotions feel unexpected. Here’s what we might expect from a straight (non-camp) girl in the same situation:

Being better than Howard at piano, she takes the opportunity to coolly demonstrate her prowess. (At no time do I read Harriet as not being just as good at “Humoresque” as she thinks she is. She’s clearly gifted in controlling the grandmother. I bet she’s gifted in other ways, too.)

But why does Harriet not take this opportunity? I have given my own theories about Harriet’s resisistance. Roupenian and Treisman list a number of related possibilities:

- Maybe Harriet is too authentic. She loves her art and doesn’t want to bring something so precious into this tawdry, pretend situation. (They agree this reading isn’t quite right.)

- The second possibility is about other kids and Harriet’s shame. She’s thinking Howard is going to tell everyone she writes poems, to shame her about being artsy and girly. Ropenian can see a feminist message in this story, but just ‘at the edges’. She may avoid exposing her art to avoid exposure as caring about something as silly as poems. This would feel especially horrible coming from someone like Howard, who is stifling his laughter and clearly thinks poems are ridiculous. In short, she’s avoiding humiliation.

- She doesn’t like to be a tool — or a doll — in the competition between two old ladies.

Adding to that, here’s my deeper take.

Stephen King famously advises writers to create the first draft with the ‘door closed’, writing as if the world will never see it. Only care in subsequent drafts about potential audiences. Other artists have said this too, but the writer must bifurcate mentally in order to get to that deepest, most scary part of oneself and bring it onto the page. Despite having previously shown her grandmother the poetry, I suspect Harriet is psychologically in the ‘door closed’ part of her art and, like many adolescents, may never ever get to a point where she shares her poems, at least not with peers. Poems are an intensely private thing. The grandmother hasn’t realised that when Harriet shared her poems with the grandmother, this didn’t mean consent to share it with every other Tom Dick and Harry. By failing to realise the intimacy that was involved, the grandmother has let Harriet down. Harriet realises in this moment that the grandmother isn’t taking the intimacy of shared poetry seriously.

Harriet as shadow self

Could it be that Harriet doesn’t think her audience is worthy? Most of us don’t think we are worthy, at least part of the time. We seek praise and attention from adults.

ANAGNORISIS

“A Shirley Jackson short story response will depend on what mood the reader is in when they read it.”

The reason I feel I understand Harriet so well is because Shirley Jackson has left me to fill in her psychology for myself. Taking another close look at how Jackson wrote the story, it’s almost like a movie script. It’s very matter-of-fact. Jackson does not break the dialogue to allow the narrator to explain what’s going on inside Harriet’s head.

Some stories lend themselves to interiority. Others don’t. The trick for storytellers is to know when interiority will benefit the narrative.

Without the benefit of a narrator offering us asides, we never do know for sure whether Harriet is a poet or if she’s been lying about being a poet. The story is left open to interpretation.

So, did Harriet write the poems? Methinks she doth protest just a bit too much. Ergo, Shirley Jackson helps the reader to understand Harriet really did write those poems. Harriet also pauses before coming up with The Home Book Of Verse — the perfect title for the kind of book this poem might have appeared in: a riff on A Child’s Garden of Verses by Charles Robinson, and all the domestic science books aimed at women with ‘home’ in the titles, perhaps.

As mentioned in the podcast discussion, this entire story turns on a single word:

She went over and took the papers out of her grandmother’s unresisting hand.

“Afternoon In Linen”

Unresisting “feels like a little murder because she’s just destroyed her grandmother, refusing to take the exits the grandmother has offered her.”

I’ve heard different writers use various terms when talking about the thing in a story which ‘makes it’. More about that here.

NEW SITUATION

The grandmother is clearly defeated. Harriet has metaphorically killed her. Harriet is the winner in this small tousle for dominance. And Harriet wears the crown in this flipped, darkly carnivalesque tale.

“Afternoon In Linen” is a good example of a short story which has emotional closure if not hermeneutical closure. (We know what the characters are feeling, we’ve been with them on an emotional ride; we don’t know if Harriet wrote the poems, was lying about them, or what.)

EXTRAPOLATED ENDING

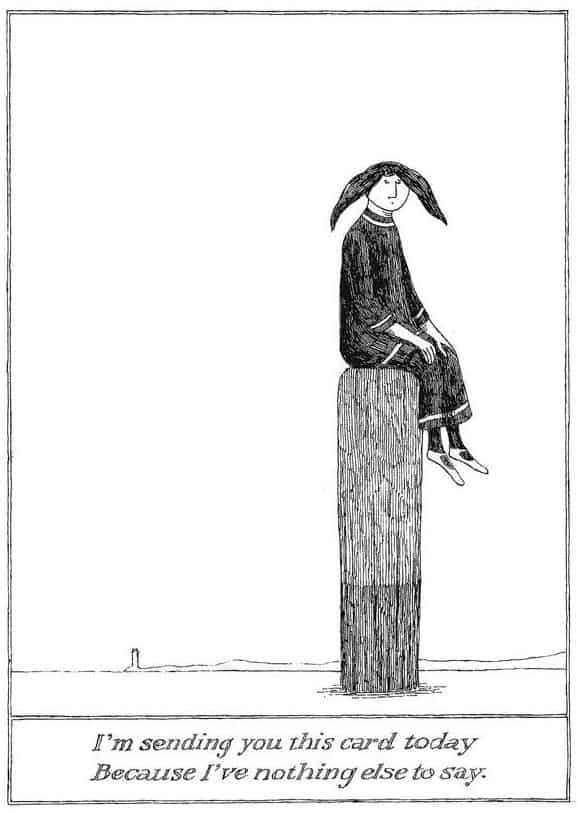

The postcard below is of Harriet, I think, later that day after her grandmother has asked her numerous times to apologise.

RESONANCE

Westernised parents and grandparents will always show off about their children, and Asian background families will keep showing off with displays of humility. Their children will keep watching and learning and replicating these cycles with their own kids, and everyone will keep being proud.

And children will be glad their parents are proud, but children do know when they are being used as shiny pawns in petty hierarchical games between adults. Children know more than we think.

FURTHER READING

I love children who lie for no reason by Elena Ferrante