A Rumour of Otters by Deborah Savage is an out-of-print New Zealand book, published 1984, written by an author from Pennsylvania. I remember there was a class set of this book in my high school, studied by Year 9 students. I wonder if there’s still a box of them in the Burnside High School resource room?

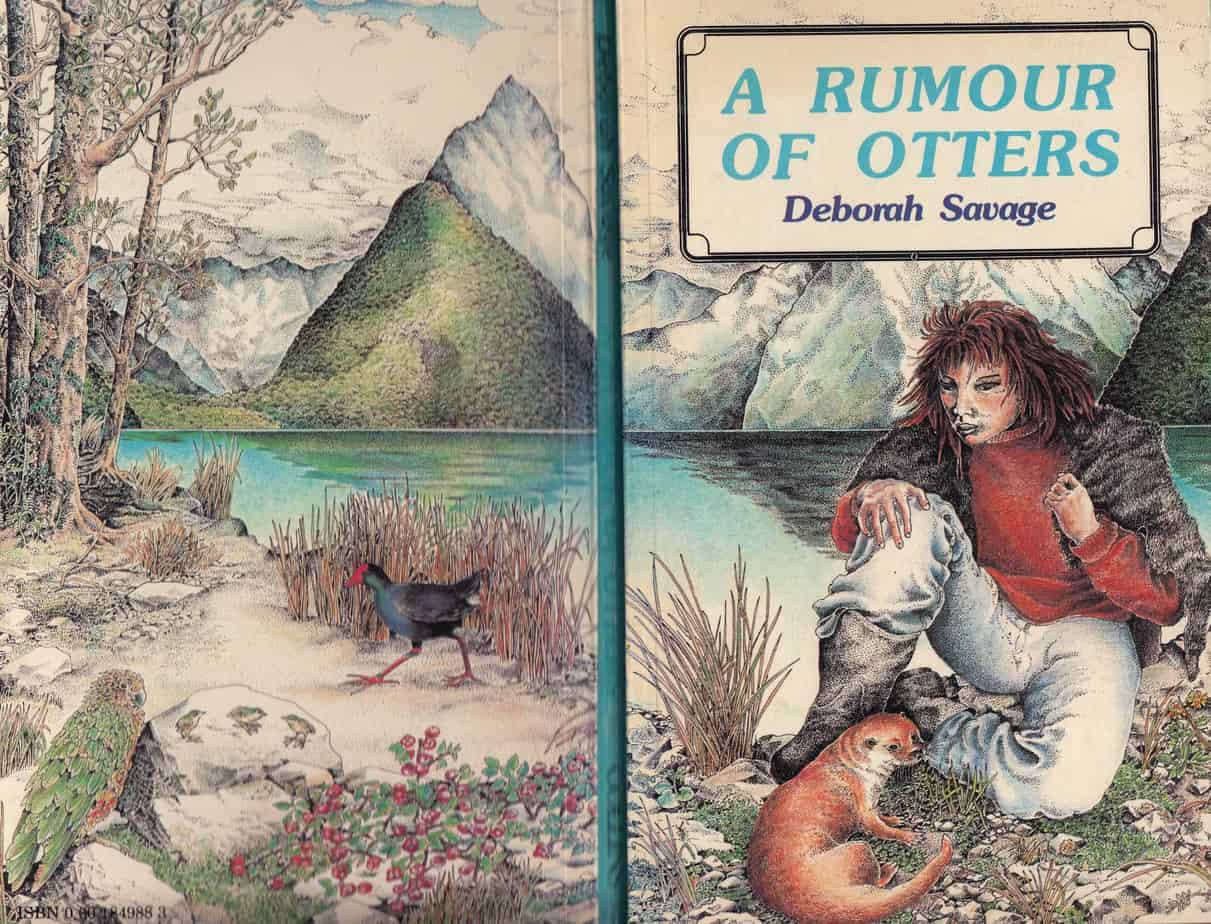

There’s something about the cover art that makes me want to scan it and put the whole double spread somewhere on the Internet.

This book is interesting for:

- Its second wave feminist ideas, not fully realised in my opinion

- Animal symbolism (there are no otters in New Zealand — the American author blended Maori mythology with Native American otter symbolism)

- Evocative descriptions of the South Island high country landscape

An extended relative gave me this book when I was seven years old, when it had first been published and could be found in New Zealand book shops. However, this is a young adult book and just because I could technically decode the words didn’t mean I got a single thing out of it, so I gave up after a chapter and, no jokes, I have been lugging this thing around for THIRTY YEARS.

“Have you been lugging anything around for thirty years?” I asked my husband. “No. Oh, hang on. I think Mum’s kept a book of poetry I wrote when I was at primary school.” (Our eight-year-old wants to see that, but her father says it’s far too embarrassing. I am disappointed that he finds it embarrassing. More to the point: he is still miffed that his story about the fire-eater got censored by the Catholic nuns.)

I am always keen to cull books if I can — believe it or not — so I thought, if I pick this up again and I still don’t know what it’s about there’s no hope for me really. Also, I no longer live in New Zealand, so it’s sometimes nice to take a cheap holiday by reading about the beautiful New Zealand landscape.

The cover art on this edition is both beautiful and grotesque. It’s that highly decorative style popular from the 1970s, and if you look at the back cover first (as I did, pulling it off the shelf) the landscape is appealingly kiwi, with the pukeko strutting across the stony shore of a pristine lake. Then you flip the cover over and see a hunched over woman with the slightly sagging cheeks of a 40 year old, head bowed as if she’s about to pounce. She’s got a 1980s rock star haircut — shaggy and shoulder-length but cut short on top. The fingers on the hands look arthritic. And that otter.

Unfortunately for me, I recently watched The Monster of Mangatiti, which is a made-for-TV movie about the true story of a predatory farmer who lured young women to his farm in the 1980s — exactly the setting of this book — ostensibly so they could tutor his young son, but he held these young victims hostage while sexually assaulting them and invoking terror. Mangatiti, while being a similar high country sheep farm, is in the North Island, so when I eventually learned this book is set near Kaikoura I was able to get that sorry tale out of my head, because my grandmother used to run motels in Kaikoura so I’m able to visualise the place without also visualising a serial rapist and significant trauma.

A Rumour Of Otters is not actually written by a New Zealander. It was written by an author from Pennsylvania who married a kiwi bloke and obviously spent some time in NZ, but with the fresh eyes of a foreigner. Savage is able to describe the landscape as if everything is new and wonderful. I didn’t realise she was from Pennsylvania until reading the flap copy after I’d read the story, but it really does explain a few things.

First: the unwitting Americanisms — the ‘toward’ instead of ‘towards’ and other minor dialect differences she wasn’t able to mask. The dialogue seems self-consciously Kiwi, and now I realise the author was simply mimicking the natives she saw around her, I can explain the over-usage of the sentence final ‘eh’. Kiwis were saying ‘eh’ a lot back in the 1980s (a la Billy T James) but you’d be hard pressed to find a native NZ author for children so proud of these speech tics that they would go out of their way to reproduce it in literature. Not back then, when there was significant cultural cringe about the way we spoke. Only an American immigrant would find it quaint.

The author’s American-ness also explains why the character of ‘the old Maori’ puts me in mind of the ‘Magical Negro’ trope. Waiting 30 years to actually read the book, this is the most cringeworthy aspect. Native NZ authors working in the 1980s were more likely to just write about white families, ignoring Maori culture altogether, which is of course problematic in a different way. In this story, white people are the norm and non-white characters are described as Maori. This had me thinking about what modern authors are doing when offering up thumbnail character descriptions — I think modern authors are more likely to give clues about cultural background rather than assume everyone is white unless otherwise specified. Our main character Alexa explores her family’s farm and looks out over ‘her’ lake, but I kept thinking how the land doesn’t belong to anyone in particular, and if it belongs to anyone, it belonged to the ancestors of those Maori farmhands sitting morose and quiet around the campfire. We’re not told *why* they’re not laughing at the white man jokes. I guess that was it.

A word on the otter. Why? There must be some otter symbolism I don’t know, I thought, and have just now looked it up on Google. Otter symbolism is not something Kiwi kids of the 80s would have had the first clue about, but an American author visiting for a few years obviously brought with her the associations from Native American culture — and now it’s all clear: In totem pole cultures, the otter is a symbol of ‘primal female energy’.

That makes total sense now. Because this story is an attempt at a female version of the mythic journey which, since Odysseus, has been almost exclusively male. What is a mythic journey? A character leaves home, has an adventure, meets characters along the way, goes into battle at some point then comes back home a changed person. He thinks he’s going on a journey for one reason but the entire reason is actually ‘to find himself’.

Second-wave feminism is at the forefront of this book. It would be difficult for young women today to identify much with young women of the 1980s, the first to have to find female role models who were nothing like their mothers and grandmothers. A huge ask. Sexism these days is much more subtle, but this is one of those stories — the last of a breed — in which a girl really wants to have the life of a man because the life of her mother looks disgusting to her.

The difficulty in writing a character like this is that she can come across as femme phobic, rejecting everything feminine, glamorising everything masculine. When she manufactures an argument with her mother accusing her mother of lack of ambition, I want the mother to say, “And what if I *hadn’t* chosen to become a mother, you little gobshite? What sort of choices would you have then, eh? You wouldn’t exist, would you. Shut up and milk the cow.” (All of that breast feeding symbolism isn’t lost on me.)

Instead, Alexa stomps around in a bad mood and doesn’t have the wherewithal to actually ask if she could go on the expedition. The answer might well have been no — for the sake of the story if nothing else — but the fact she doesn’t use her words is so frustrating to read. Instead, we see her packing a huge sulk, throwing things around and finally, after telling her mother she’s an idiot for wanting to just be a farmer’s wife (we see later the mother is caring for a new baby AND mending fences — there’s no ‘just’ about being a farmer’s wife), she decides to piss off into the mountains right on the cusp of winter.

Alexa is a fucking idiot. Any farm kid would know the risk of hypothermia. She doesn’t even take a snack, much less a coat.

This is all useful for the plot of course, because she has to go full primal, eating fern roots and cutting the coat off a dead goat. I’m reminded of the descent into madness in Margaret Attwood’s book Surfacing, though it’s done much more convincingly there.

In a hypothermic slump, Alexa imagines up the otter, who offers her an eel.

Meanwhile, her poor mother (who we must imagine) must think her daughter is done and dusted. She calls the rescue helicopter, which I might add, is run wholly on donations and preferably shouldn’t be used for teenage girls who go off on sulky missions to find themselves, and was sure to be going out of her mind.

Meanwhile we have alternating chapters with the brother. Because let’s face it, Alexa doesn’t really do enough to fill an entire book. For some action we need to see what the men are up to, rounding up sheep in a difficult landscape.

The Magical Maori knows exactly where Alexa has gone to, and the brother has some sort of psychic connection to his younger sister. He ‘just knows’ that Alexa is on some inner journey of her own and is far in advance of him in some primal way. So like a cavalier of yesteryear he puts his own life at great risk by plunging into an icy river to try and save her. (He can see her standing on a cliff or something, waving the red scarf.)

Meanwhile, a red scarf somehow leads to Alexa’s epiphany. We’re not entirely sure what that epiphany consists of; maybe she’s finally learnt not to be an asshole.

At this point in the story the author must have realised she can’t exactly manage a feminist journey if her heroine ends up rescued by her older brother, so at the last moment Tod gets stuck on some sticks and Alexa ends up saving him. Haha, they joke, isn’t that back to front.

It wasn’t until Alexa got back that I realised maybe she was *lost*. Alexa had been having such a phat time on her solitary excursion into the wild that this whole time I thought she’d wanted to be there. This doesn’t really improve her in my estimation, since getting lost on your own family’s station is just… silly?

The final paragraph hammers home the point that Alexa is the otter. ‘He was content’, we are told. ‘He had just eaten an eel, and had lain curled against the other otter on the rocks. And then quietly, as he had come, he sank beneath the black surface again. The stars fell together once more on the water. Nothing moved.’

I take it Alexa went to the pictures with that much older farm hand (the one with the soft but strong body, like a horse), got married and became a farmer’s wife, after realising, via this journey, that the wilderness is no place for a girl after all.