“A Real Life” by Canadian author Alice Munro first appeared in the February 10, 1992 edition of The New Yorker.

You’ll also find it in the Open Secrets collection published two years later. Almost all of these stories are New Yorker stories.

In this story, Alice Munro asks us to consider what makes a meaningful life, especially for a woman. If she never marries or has children, how does she make a meaningful life for herself? What might this look like in the 1930s?

Let’s take a moment to draw from biographical details. As a girl, Alice Munro was clearly asked to consider what a ‘proper’ life for a grown woman looks like:

Reading wasn’t really encouraged in her family. Once it was obvious that Munro had turned into a serious reader, her mother referred to her as “another Emma McClure!” McClure was a recluse relative of theirs who, according to Munro, “had been reading day and night for 35 years, with no time out to get married, learn the names of her nephews and nieces or comb her hair when she came into town.”

90 Things To Know About Master Short Story Writer Alice Munro

AITA for telling my husband’s tenant (and my friend, I guess) that the only house she’s ever known was already sold so she’d not back out of marrying an Australian and move to the other side of the world forever in the 1930s?

Hey, so I (she/her) had this old friend (probably they/she, if I ever asked about pronouns in the 1930s). Well she was a strange kind of friend, like me in some ways but so different in others. I’m married, she’s resolutely single. I like to keep a nice house. Let’s call this friend Dorrie. Long story, but Dorrie’s family went broke and for years Dorrie rented the house my husband owns on one of his three farms. Dorrie and I sort of became friends due to proximity. She’s actually pretty needy. Her family used to be wealthy but her parents lost all the money because of, you know, the Great Depression and whatnot. Oh, I said I wouldn’t get into that.

In case you’re wondering, I do have another good friend. Her name is Muriel Snow. I’m not completely without woman friends, even though many of the wives around have always considered me beneath them for marrying a simple farmer. (My husband has three farms, and he’s every bit as hard working as their professional husbands, but I digress.)

I held this dinner party some time back and invited the minister. I’ve always enjoyed Anglican traditions. The minister brought an Australian guest with him. I also invited Dorrie. Well. He and Dorrie really hit it off. I am so happy to be instrumental to have set that pair up, even though I didn’t think for a moment it would happen. Dorrie was so crass that evening, waltzing in late wearing goodness knows what, then announcing to the whole party that she’d just murdered and sacked a feral cat which may or may not have been someone’s pet.

The love birds corresponded for months, and then great news! The Australian asked Dorrie to marry him! Or she asked him, who knows. He probably fell in love with her beautiful hand-writing which she learned at that finishing school she’d been sent to as a young woman. (I plan to send my own daughter there. It’s important to marry well, especially for girls.)

I have been nothing but helpful when it comes to helping Dorrie prepare for her new life in Queensland, Australia. My best friend Muriel and I have made her wedding dress and basically planned the entire wedding. Dorrie should be lucky to have a friend like me, and also my friend, to help her with all this wedding palaver because she’s never given a thought to how her wedding might look and her house is a mess. I mean, she can’t really manage life, this woman. She’s never even left home, still lives in the ramshackle house where she grew up. (You should see the kitchen. It’s a state. She can’t even make a decent cup of tea. I once found dog-dirt at the top of the stairs. Then I started finding it everywhere. After a while it looked like it belonged there!)

I say all that, but I’m not judging her harshly. No, not at all. Despite all these other observations, Dorrie is somehow, inexplicably, a real lady. Finishing school. For all her hunting, shooting and trapping she’s a lady.

For decades, scientists have believed that early humans had a division of labor: Men generally did the hunting and women did the gathering. And this view hasn’t been limited to academics. It’s often been used to make the case that men and women today should stick to the supposedly “natural” roles that early human society reveals.

Now a new study suggests the vision of early men as the exclusive hunters is simply wrong – and that evidence that early women were also hunting has been there all along.

Men are hunters, women are gatherers. That was the assumption. A new study upends it.

So, a week before this wedding, Dorrie gets the jitters. That’s only natural. Pretty much every woman I know wonders what she’s in for, and it’s no small thing moving from Ontario to Queensland, Australia, right? I certainly had no idea what I was in for. My own husband is 19 years older and on our wedding night he told me, “Now you have to take what’s coming to you.” He didn’t mean it unkindly, but I sometimes wonder what would’ve happened if I’d said no. Anyway, I quickly gave him three children and he’s not a bad husband really because after complications with the third he didn’t want to risk me dying, so he left me alone in the bedroom after that. And I’m happy about that, I am. He’s a good husband. A very good husband.

A week before this wedding between Dorrie and the Australian, I invite Dorrie round for supper because, well, I’ll be shot of her soon anyway, and she needs support at this difficult transitional time in her life, but who’s the rude one? She doesn’t show up! I go over to her house and find her in her (horribly unkempt) kitchen and she doesn’t want to get married now. Oh Millicent, she says, I can’t move to Australia! I’ve realised I like my life as it is!

Pfft. Dorrie’s life is no life at all. I mean, this is a woman with no husband, no children. She’s got no one too cook for, no man’s washing to keep her occupied. No motivation to keep a nice house. She’s been coming over and talking to Porter and I more and more since that Labrador-cross of hers died. (Porter’s my husband’s name.) She wouldn’t have needed to get married if her brother were alive, but he’s not. The only hobby Dorrie ever had was feral: catching muskrats and shooting rabbits with that beloved Labrador she had, but since the Labrador was run over by a car there’s absolutely nothing to justify her staying right here in rural southern Ontario.

I talk her round. Yes, I talked sense into her. I may have cried a little, thinking of what her life would be like if she stayed here on the farm forever. She’d be so lonely. It’s almost a sin to give up this opportunity. I knew already what she couldn’t see at the time. This was Dorrie’s one and only chance to get a life. Let’s face it, she’ll never meet anyone else who’ll marry her. I mean, she’s not exactly housewife material. (I’m not being mean, but she had a local horse named after her.) And she’s not getting any younger.

So I tell a small porkie. It rolls off my tongue just like that. I inform her that, unfortunately she can’t stay anyway, because my husband has already sold the house. She’ll have to move out and start somewhere new no matter what, so she may as well go through with the plans she made with her Australian fiancé.

This is not true, of course. The house hasn’t never sold at all, in fact it’s built so solid it won’t even fall down, but I figure she just needed a little nudge. Sometimes we all need a little nudge. She couldn’t see how pathetic her life is, but I have a clearer view of Dorrie’s life from my slight distance across the way. It’s not good for a grown woman to hang about in her old family home, around all these ghosts — dead parents, dead brother, dead dog and not a stick of furniture to remind her of the life she once had.

But since then a few decades have passed, and it turns out Dorrie’s Australian husband died after WW1. She’s had a wonderfully adventurous life, and even learned to fly a plane! She sends me photos, and I can see she’s gotten very fat.

And then she died aged fifty, in the middle of some big adventure in New Zealand. She died doing what she loved.

Dorrie would never have had such an adventurous life had she stayed put. I’m proud to have played a part in kick-starting her real life.

I have quietly wondered about my decision to lie, however. I lied that the house had been sold. Is that ‘coercion’? There are white lies and proper lies; everyone knows that. But is there such a thing as good coercion and bad coercion? When does a little nudge become coercive? I’ll leave that up to readers to decide.

OPEN SECRETS (1994)

- “Carried Away” also in the October 21, 1991 edition of The New Yorker

- “A Real Life” also in the February 10, 1992 edition of The New Yorker

- “The Albanian Virgin” also in the June 27, 1994 edition of The New Yorker

- “Open Secrets” also in the February 8, 1993 edition of The New Yorker

- “The Jack Randa Hotel” also in the July 19, 1993 edition of The New Yorker

- “A Wilderness Station” also in the April 27, 1992 edition of The New Yorker

- “Spaceships Have Landed“

- “Vandals” also in the October 4, 1993 edition of The New Yorker

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS FOR “A REAL LIFE” BY ALICE MUNRO

- Although this story is largely set in the 1930s, there are parallels to how women live today. Do you find it easier to identify with one of these characters more than other? How and why?

- What were the social forces which led each woman to make the choices that she did? In what large ways did life look different for Canadian women in the 1930s?

- When Millicent makes all of those preparations for the magnificent party, what does this say about her character?

- When Millicent lied to Dorrie about having sold her house from under her, thereby forcing her hand in marriage, what were all the factors contributing to the lie, both consciously and unconsciously held by Millicent herself?

- Millicent would dearly love to be included in the friendship group of the upper-class women. How do we know this?

- Alice Munro has given us a character study of three different “types” of women. What are those three main female archetypes, and do you think we still divide women up into these same categories today?

- Do you feel Dorrie had a happy ending? And do you believe Dorrie, via her letters, was a reliable narrator, really doing all of those things? Why or why not?

- How would you rate Millicent’s marriage to her husband? Happy, unhappy, somewhere in between? What clues do we get?

- Why do you think Millicent is so invested in what Dorrie’s up to?

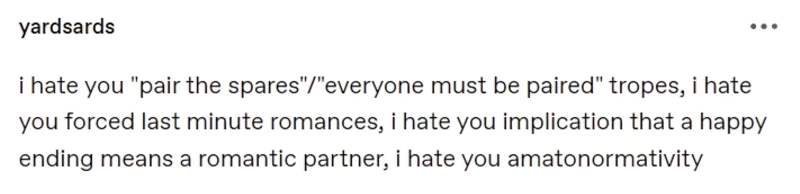

- In the end, all three women end up getting married. Why do you think Alice Munro chose to marry all three of them off (even though Dorrie’s husband soon dies)? What is she saying about women’s lives in the 1930s?

CHARACTERS IN “A REAL LIFE”

DORRIE BECK

She was a big, firm woman with heavy legs, chestnut-brown hair, a broad, bashful face and dark freckles like dots of velvet. A man in the house had named a horse after her.

“A Real Life” by Alice Munro

When young, Dorrie attended Whitby Ladies’ College, finishing off the last of the Beck family money. The Beck family were forced to sell their family farm. (Not to the Becks, who own the land and house now, but to a previous owner who since sold.) These days they rent their old house back from Porter. They were also required to sell the family furniture. Dorrie was left with an unfurnished house, and no means of refurnishing it. Even the carpets and pictures were sold.

Dorrie’s parents wanted a better life for her. At the expensive finishing school she learned to use her knife and fork like a lady and fine handwriting, but nothing actually useful. Only surface-level stuff, as is the entire point of a ladies’ college. Her parents must have thought this was her best chance at a good life — attracting a wealthy man. However, Dorrie has learned farm skills regardless and has the strength of a man.

In the 1930s Dorrie lives alone in a ramshackle farmhouse near the town of Walley. She previously lived there with her brother. Dorrie likes to trap muskrats and shoot rabbits with her Labrador, Delilah. But one day, Delilah is killed while chasing a car. Dorrie seems to take this in her stride, but surprises Millicent later by referring to the dog as a ‘pet’ (as opposed to a hunting dog).

The entire village is bemused and belittling when it is revealed Dorrie is to be married. Who would marry her? The groom probably won’t even show up! Jokes are made about cobwebs (referring to lack of penetration by a man, of course; I explain the metaphor to highlight the crudeness of the heteronormative townsfolk.)

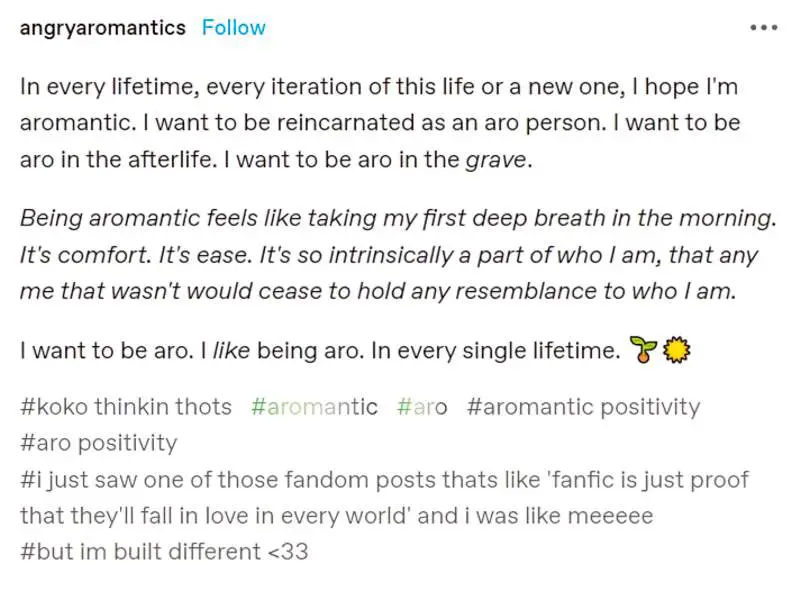

But it is Dorrie who experiences serious pre-wedding jitters and almost backs out, if not for her ‘friend’s’ interference. Dorrie realises she’s happy alone and doesn’t need to be romantically paired with anyone before living a decent life.

After marrying an Australian and moving to Queensland, her husband dies after the war. She works on the farm there, grows old and fat, then dies in the 1950s while climbing a volcano in New Zealand. She has led an adventurous life, which would not have been half as adventurous had she not married the Australian traveller in the first place.

ALBERT BECK

Dorrie’s brother. Deceased. While alive, Albert was a protective figure. In those days women needed a man to be economically and socially viable. If not a husband, at least a brother. He was a grocery van driver. Albert, too, was educated but wasn’t the same after returning from the war. He sought an outdoors job and was a real people person. He became the local guy you call when you need a lift.

PORTER

A farmer who owns Dorrie’s house. He despises church and won’t go. The pre-marital agreement was this: Porter would provide materially for his wife and she would ‘take what’s coming to her’ in the bedroom, though he doesn’t say this unkindly.

MILLICENT

Millicent’s father died of complications from alcohol addiction when she was ten. As a young woman, Millicent was well-educated (for a woman) and taught school. She did not marry early, rejecting two serious boyfriends.

She likes her Anglican traditions, especially the traditions and the singing.

In 1933 she becomes Porter’s wife. Porter is 19 years older than she is, owns three farms and promised her a bathroom within a year of marriage. Also nice furniture. In a Pride and Prejudice comparison, Millicent is reminiscent of Charlotte Lucas. She most wants economic stability from a man. She held out until she encountered it. Now she will carry out her duties as a woman.

She quickly gives birth to three children. The third pregnancy has complications and after that Porter no longer bothers her for sex. Does she want it? Other readers interpret Millicent as frigid. I don’t think so. I don’t think this ‘third person narrator’ is reliable. The husband is likely terrible at it. Pregnancy was literally life-threatening back then, and it may not have occurred to this couple, living in a phallocentric world, that other sexual things can be done in the marital bedroom which do not result in pregnancy. I don’t think ‘frigid’ is the word here. It’s more, practicality. But if there’s no sex (or romance) left in Millicent’s marriage, she’ll look for it in the life of the mind. Some women read romance novels. Millicent has her own coping mechanism: She’s Emma in a Jane Austen novel, imaginatively embedding herself in someone else’s romantic life: Muriel’s and Dorrie’s by turn.

Millicent is Dorrie’s landlady and also Dorrie’s only friend. Millicent is ostracised by the wives of local professional men because her husband is ‘only’ a farmer. Rather than despise the upper class, she can’t help but aspire to it. She means to send her own daughter to Whitby Ladies’ College, where Dorrie learned table manners and beautiful hand-writing.

Millicent’s best friend is an unmarried, sexually promiscuous piano teacher called Muriel Snow.

One day, Millicent gives a party for the Anglican minister and his guest, an English-born Australian. She invites Dorrie, and notices the two have more in common than expected. They both use a knife and fork in the same way.

When she learns Dorrie will be marrying Wilkinson Spiers, Millicent makes her dress and plans her wedding. But a week before Dorrie is due to be married, Dorrie fails to show up for a pre-arranged supper at Millicent’s. Millicent goes to Dorrie’s house and finds her in her kitchen. Dorrie explains that she wants her life to stay the same.

Millicent tells Dorrie that this is her chance at a real life. She also lies, and tells Dorrie that her husband has already sold the house anyhow, basically forcing Dorrie to go through with the wedding. After all, everyone must get married. We must pair the spares!

In her old age, Millicent wonders if she behaved morally in coercing Dorrie to marry by lying that her house had been sold from under her.

MURIEL SNOW

Millicent’s best friend. The pair met because Muriel is Millicent’s daughter’s piano teacher.

Muriel helps Millicent make Dorrie’s wedding dress when she marries the Australian.

After Dorrie’s wedding, Muriel moves to Alberta and marries a minister, renouncing her earlier life.

Muriel Snow isn’t sufficiently ladylike for Millicent’s liking. She says Chrissake, hot damn and poop. She smokes. At the age of 30 she hasn’t settled on a man, but instead has flings with men she meets, whether they’re married or not. She insists she’s only having fun, and pays no regard to the wives, or what they might think of it.

As a wife and mother herself, Millicent can’t approve of this lifestyle and they have an argument over it, soon mended. Millicent seems somewhat attracted to Muriel herself, and Alice Munro shows us some minor flirting when Muriel tells Millicent that everything she’s wearing is made of satin.

The fabric of satin becomes associated with this character. Later, Dorrie’s wedding dress will be made of the same fabric, but there’s no discernible sexuality to Dorrie and Millicent — like we are — is surely associating satin with the very visible and “bewitching” sexuality of Muriel.

But even Muriel is tamed by the cultural expectations that women marry. She marries a widower in Alberta who has two children. She is now a step-mother, a woman who conforms, who lives her life more for others. Hilariously, he is also a Christian minister. It’s as if she has married the most conservative man she could find to beat the wild spirit out of herself. She no longer drinks, smokes or wears make-up.

What happens to Muriel is the inverse of what happens to Dorrie, but their stories are still flipsides of the exact same coin: Women tamed into marriage and conformity.

THE ANGLICAN MINISTER

Even Muriel can’t spark his interest. A 1990s reader (and beyond) will likely deduce that the Anglican minister and the friend staying with him is gay. This would not have been the default assumption in the 1930s, as evinced by the worldly Muriel giving it a crack. “Neither fish nor fowl,” she concludes, meaning she simply can’t work him out.

It’s also possible that one or both of these men is asexual, if not both straight. My reading: Wilkinson Spiers is andro-attracted, meaning he’s attracted in some way — perhaps not always sexually — to masculinity and masculine traits — be they in men, masculine women or in masc presenting non-binary people (before there was ever such a word). In any case, it’s unlikely a marriage motivated by sexual needs. The heavyset, outdoorsy Dorrie would make a perfect farmer’s wife. This marriage is a job contract.

The clue: Wilkinson Spiers and Dorrie have a different sort of pre-marriage contract from the one Millicent bargained for. She refers to her marriage as ‘a form of marriage’, which she clarifies only to say there will be a marriage ceremony. Whatever happens (or doesn’t happen) after that is between Dorrie and Wilkinson Spiers.

WILKINSON SPIERS

The Australian guest of the minister. People assume him to be English which suggests either that the Canadian locals don’t know the difference. It is revealed that he was born in England. (Compared to today, the standard white Australian accent of the 1930s did sound quite English, especially if you were well-educated. So any educated white Australian probably sounded English to Canadians.)

Spiers appears smitten with Dorrie, and exchanges letters to her even after returning to Australia. Dorrie agrees to marry him.

He marries Dorrie but dies after WW1 (“The Great War”).

WRITING TECHNIQUES OF NOTE

A ‘BETWIXT AND BETWEEN’ NARRATIVE VIEWPOINT

Where is the narrative voice coming from, exactly? How consonant is this voice to the interiority of Millicent, and how much comes from some unseen, unknown narrator? I believe Alice Munro’s narration sits somewhere between Millicent’s and omniscience.

For example, the opening paragraph sounds like the voice of someone we soon learn to be Millicent:

A man came along and fell in love with Dorrie Beck. At least, he wanted to marry her. It was true.

“A Real Life”

If this were an omniscient narrator, there’d be no need to assure readers of the truth of it.

If this is so, what can we trust of the third person narration when it describes Millicent? Is this an unattached observer speaking, or is it Millicent’s idea of herself:

Millicent was not an uneducated person herself.

[whispers] I’m not an uneducated person myself.

“A Real Life”

The conflation of first and third person is finally explicated in the final paragraph:

But I would not allow that, thinks Millicent. She would not allow it, and surely she was right.

“A Real Life”

This voice also feels like the so-called ‘village voice’ — it must be someone who knows all these characters very well, or at least thinks she does. The stories she tells seem to come partly from chatting with Dorrie. For example, the things Millicent knows about Albert and the women he meets on his grocery run come from Dorrie.

Why might Munro write with an ambiguous narrative voice? Because this is a story about morality. Like the AITA subreddit, we are invited to sit in moral judgement of her. As part of that, we must determine for ourselves which parts Millicent (or Millicent’s ‘third person equivalent’) gets right. Where might she be judging herself harshly? Where might she be giving herself a pass? The reader must read between the lines here, which is why the narrative viewpoint, too, sits in that in-between space.

As you read, you may find Millicent (as third person) to be an unreliable narrator. For example, it’s clearly not Dorrie’s table manners and ladylike handwriting which attracts the visitor to her, but her stereotypically masculine interests. He has just been reading a book about hardships along the Oregon Trail, so it makes sense he’s enthralled hearing Dorrie talking about her hunting trips, and skinning rabbits, preparing them for table.

A CROSS-GENERATIONAL STORY

Annie Proulx is a short story writer well-known for writing three generations if she writes a character. There are various reasons why she does this. She tends to explain the family history up front, near the beginning of a story.

Alice Munro starts her story in a conversational tone which perseveres throughout. We don’t hear about the history of Dorrie’s family all in one go, but in dribs and drabs, as if from someone (Millicent) sitting across from the kitchen table, thinking of information as it comes to her.

This may not sound as majestic as Annie Proulx’s way of doing it. (Somehow Proulx’s stories feel as significant as the Wyoming mountains.) But the effect is the same. It’s important to know about Dorrie’s background and the sociocultural factors which led to her being in this situation — completely alone in the world.

THREE WOMEN: THREE FEMALE ARCHETYPES

A man is a man is a man, but women get to be one of three things according to popular imagination, especially in the 1930s:

- mother

- wh*re

- virgin

Millicent is the mother, Muriel is the loose woman about town (ironically named Miss Snow), and Dorrie is the virgin/celibate. When she comes to dinner, significantly, she is dressed in what Millicent deems an outfit suitable for a little girl or an old lady (two other life stages which are either pre-sexual or desexualised). Muriel mistakes the minister for his guest, showing that she doesn’t really care about men. In contrast, we’ve seen Muriel make a stage entrance, telegraphing her sexual availability. Dorrie goes on and on about catching and sacking a feral cat.

Alice Munro could have written this story without the character of Muriel, but what would we lose? It’s important to show to sexual extremes because this highlights the reality that a mother sits between them.

In common with her friend Muriel, she understands what it is to have sex, and to be physically close to men. But in common with Dorrie, she is these days celibate. Her husband gave up on sex after the third, complicated (and we can assume, dangerous) pregnancy.

The reader is invited to pass judgement on all three of these women, and then reserve or reverse judgement as more information becomes available. By clearly positioning these women as The Three Female Types, and by witnessing the factors which go into each of these women’s life choices, we might (hopefully) start to question the boundaries and usefulness of these archetypes.

THE MEANING OF ‘REAL’ IN THE TITLE

When someone tells another person to ‘get a life’, this is a judgement on every single thing about them. Not only that, it suggests that there’s a way to live that is real, and a way to live that is null. To ‘get a life’ suggests no life exists in the first instance.

Though the insult is more recent than the 1930s, Millicent is basically wanting Dorrie to ‘get a life’.

Not for Dorrie’s sake, but out of her own vicarious interest. Those who’ve already partnered for life (in which case you only get to do it once, ever) are frequently very interested in the partnering life stage of other people, interfering as a way to get a do-over themselves. When it is Millicent who cries near the end, comforted by Dorrie, we see how (over-)invested Millicent has become in Dorrie’s personal affairs. Ironically, it is Dorrie who ends up exploring the world, and Millicent who remains planted in place, bearing witness to the increasing dilapidation of the long-gone Dorrie, side-shadowing a life for Dorrie which was lonely and unadventurous. This side-shadowing comes naturally to Millicent because, of course, this Millicent’s life. Not the life she imagines for Dorrie at all. This is deflection.

There is an ache in my heart for the imagined beauty of a life I haven’t had, from which I have been locked out, and it never goes away.

Robert Goolrick, from The End of the World as We Know It: Scenes from a Life

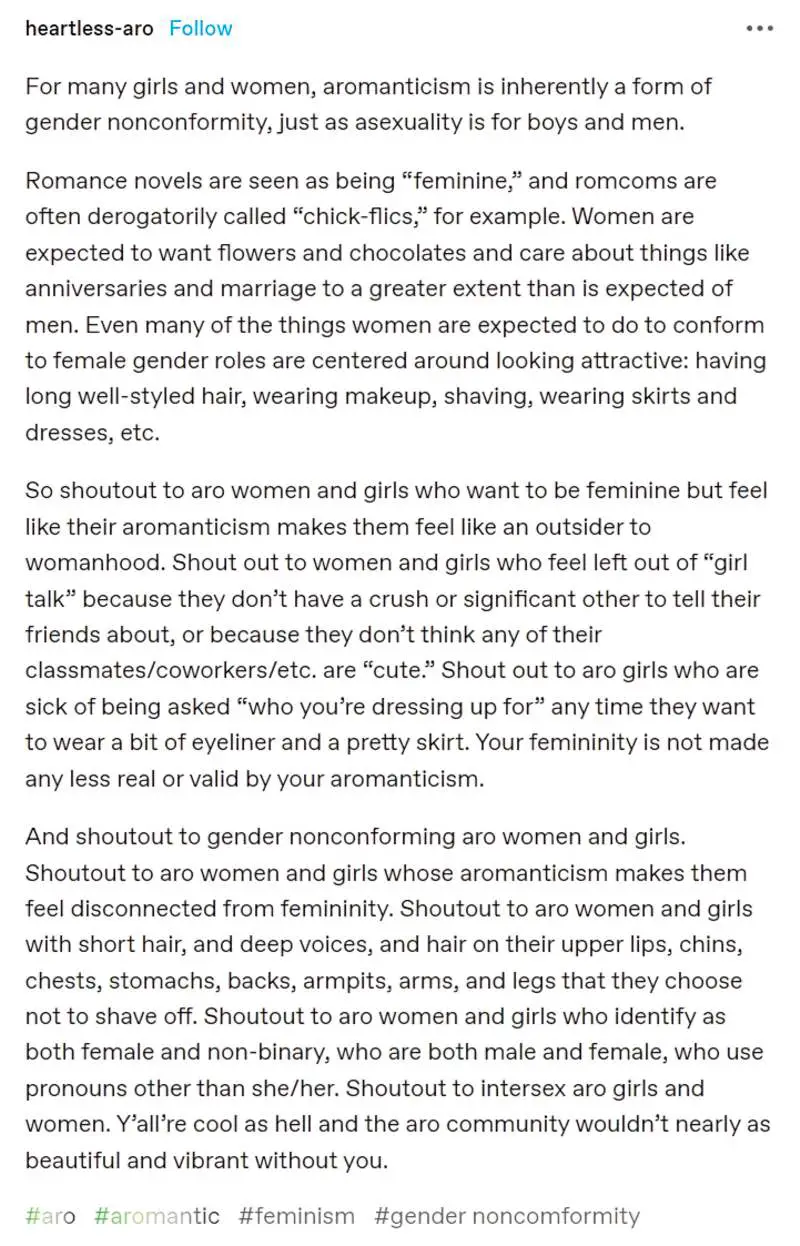

A life without adventure is still a life, and house-wifing is perfectly fine life, too. What might be the inverse of ‘real’? Aside from ‘null’, there’s also the ‘fake’ life, lived for and through other people, in a way that women feel most keenly. Notice that Millicent mentions several times that, despite her gender non-conformity, Dorrie is still a woman. Meaning, so long as Dorrie is considered a woman in a gender binary culture, she is subject as any woman to the rules of femininity. Indeed, they clang down more harshly on the women who don’t/can’t conform.

As a wife and mother, Millicent is fully acculturated into living for her husband and children, subsuming her own desires in the hope her own daughter will do better than she did. Explaining her acculturation, Millicent has been ostracised by the wives of professional men and this burns. She’s stuck with the likes of Muriel and Dorrie, and she does not want that for her daughter. She understands how the world works, how this little community works, and she is doing everything in her power to give her daughter the appearance of an upper-class girl, hence the piano lessons (ironically taught by the fastest woman in town).

Be it silk or satin, shiny fabric functions as a motif in this story (meaningful repetition) and in “A Real Life” stands for surface over substance. Both silk and satin have a shimmery quality which reflects and deflects. Whereas Muriel wears silk, Dorrie will wear the cheaper fabric on her wedding day.

Whereas silk is a natural fabric, satin is the cheap, manufactured (fake) equivalent. This is the reader’s cue: There’s something wrong about this marriage from the start. Marriage just doesn’t suit the likes of Dorrie, and it starts with the cutting of fabric for her wedding dress.

Its broad, bright extent, its shining vulnerability, cast a hush over the whole house. … Dorrie, who could so easily slit the skin of an animal, laid the scissors down. She confessed to shaking hands.

“A Real Life”

A CRITIQUE OF AMATONORMATIVITY

We can thank Alice Munro for critiquing the notion that everyone must get married before finding happiness in life, and for creating in Dorrie a relatable aroace character who doesn’t care about being a sex object, hasn’t given a thought to how her own wedding might look, is perfectly at home with a good dog and who is unabashedly, unashamedly herself.

Alice Munro doesn’t do what readers may want; Dorrie does get married, because the culture of the time means marriage, even for someone like Dorrie, is written in the stars. She is basically fated to be married off. With no concept and no model for who she might be, she allows herself to be swept along by Millicent and Muriel.

Munro does a few other things which will resonate with queer readers, for instance the metaphor of stopped clocks in Dorrie’s house. For queer people, time often works differently. Forced to go through two adolescences (one as ‘straight’) and a later, more enlightened one, time works differently. Firsts are later. (And sometimes there is no normative ‘first’.)

Chrononormativity refers to a culturally shared belief regarding when people should have achieved certain things by what age. (Be moved out of home by 20, graduated by 24, married by 25, children by 30…) The clocks stopping, and Dorrie’s generalised lateness (not just to dinner, but to life) is a comment on how Dorrie is perceived to be too late, in general, as a person. And she is harshly judged for her failure to ‘keep time’, as a woman.

The bare walnut tree growing outside Dorrie’s house complements the clock metaphor.

It was a warm evening, and the back door of Dorrie’s house was standing open. Between the house and where the barn used to be there was a grove of walnut trees, whose branches were still bare, since walnut trees are among the very latest to get their leaves. The hot sunlight pouring through bare branches seemed unnatural.

“A Real Life”

Dorrie is, of course, the walnut tree — late to get her ‘leaves’, a late-bloomer — at odds with her social environment which expects her to be paired up with a man by now.

THE REVERSAL AT THE END

It would not be Munro’s M.O. to give Dorrie a lonely, hard-scrabble and lonely life in Australia. No, what Munro does is this: A character is faced with a moral dilemma, makes a questionable decision which could be terrible, but actually things don’t turn out 100% terribly. The consequences have nuance.

The ‘main character’ in this story isn’t Dorrie, anyway. We’re never let inside Dorrie’s head. Everything Dorrie feels is filtered through Millicent. And Millicent’s observations about Dorrie (who ironically is the one with ‘no life’) tell us more about Millicent than about Dorrie.

How does Munro show this? It’s shown all the way through the story, but explicated in the end, with Dorrie-as-House.

It’s not uncommon for authors to turn buildings into characters. In fact, whenever a house is described in fiction, readers can expect the house really describes its inhabitant(s), even if ironically so. Here, the house is ironic — a tumbledown, lonely-looking place while its original occupant is off having a ball, travelling the world, flying planes and whatnot.

Alice Munro utilises this house-as-character trick, but goes one further with it. The woman left behind has the house to remind her of the life she imagines Dorrie could have had. Those windows really reflect her life. She had expected the house would soon fall down after Dorrie’s permanent departure, but there it stands, stolid as ever.

Life hasn’t gone as she expected at all, not for Dorrie, not for herself, and not for that solid brick house.

CREATING A LIFE WITH INTENTION

How might we avoid ending up like Millicent? Millicent has failed to interrogate her decisions. She has let culture and circumstance sweep her along. Did she really want to be married? Did she really want children? Or did she want the social prestige and security which goes part and parcel with those things, especially in the 1930s?

There’s that word again: real(ly).

In some ways, we can’t blame Millicent for her (lack of) choices. It was only after WW1 that it became acceptable for a woman to live alone, without a husband, father or brother. Until then, women on their own could not set up shop, have a job or her own income, at least not outside the realm of domestic servitude and sex work. Millicent never even expected to have a say in politics. In Canada, white women didn’t achieve suffrage until 1918. We can hardly blame Millicent for her curtailed, domestic aspirations, or Dorrie, for that matter, for going ahead with her marriage despite huge reservations.

But for contemporary readers, with far more opportunity for a self-actualised life, are we any more free than Millicent?

Greg McKeown Essentialism: The Disciplined Pursuit of Less (2014)

Have you ever:

• found yourself stretched too thin?

• simultaneously felt overworked and underutilized?

• felt busy but not productive?

• felt like your time is constantly being hijacked by other people’s agendas?

If you answered yes to any of these, the way out is the Way of the Essentialist.

Essentialism is more than a time-management strategy or a productivity technique. It is a systematic discipline for discerning what is absolutely essential, then eliminating everything that is not, so we can make the highest possible contribution toward the things that really matter.

By forcing us to apply more selective criteria for what is Essential, the disciplined pursuit of less empowers us to reclaim control of our own choices about where to spend our precious time and energy—instead of giving others the implicit permission to choose for us.

Essentialism is not one more thing—it’s a whole new way of doing everything. It’s about doing less, but better, in every area of our lives.

- If you don’t prioritise your life someone else will.

- Determine what’s important in your life.

- Trim the inessential.

- Create a system which makes the essential things easier to sustain.

- We’ve been conned into thinking we should have it all.

- In the 1930s, we compared ourselves to our neighbours (as Millicent compares herself to Dorrie and the wives of the professional men.) These days we have even more pressure because we also have our ‘social media neighbours’ contributing to our personal aspirations. We even compare ourselves to celebrities.

- The big con: In order to get everything that everybody else has, we must do everything all of the time.

- None of this is true. We don’t have to have it all. It’s not true that if we try to do it all we will get it all. None of it’s real. None of it’s actually workable. None of it delivers on what it says on the packaging.

- Every single person has too much to do, too much pressure and is dealing with this challenge at some level. Every person, because of that reality, is in a sense expert at saying no. We don’t actually say “no”, but as soon as we load our plate of expectation with far more than we can possibly do, that means by definition that many other things will not be done.

- Life is fast, full of opportunity and we’ve been conned into believing we can have it all.

- The question: Are the things, at the end of each day, did the least important things fall off the to-do list? And did the most important things stay in? What trade-offs did you make today?

- Even when we’re not making a choice, we’re making a choice.

- We do not have the choice to not have trade-offs. We only have the choice to either let life define the trade-offs, or to define them consciously ourselves. It’s in that awareness that we can either consciously choose the essential, or unconsciously choose the non-essential. Thereby we start to discover a greater freedom.

- This allows us to become aware of our choices, and helps remind ourselves that we can choose different trade-offs from other people. We can choose to go big on one thing even though other people are trying to do five different things. I can do the things that really matter to me.

- Next, start saying no to things.

- Whether our decisions be conscious or unconscious, we all say no to things every day. Do I get to choose those things, or do I just let circumstances and societal expectations choose for me?

- The very first step is in telling yourself “I have a choice. The way to avoid being carried along on societal expectations is to start by telling yourself: “I am choosing. I get to choose.”

- Next, make minor alterations to your language: Replace “I have to…” with “I choose to… because…”. (Fill in the blanks.)

- Individuals often feel like they don’t have a choice. Other people do, but they don’t. They’re compelled by their boss/finances/family to do certain things, live in a certain way. Even in scenarios with few obvious choices, there will still be opportunity to claw some of that decision-making back.

- This realisation that we can choose how we live our lives, how we spend our time in accordance with our own needs and desires comes with tremendous liberty. But it also requires tremendous courage. We must admit to ourselves that we’ve been choosing the wrong things, the wrong life.

- There are consequences to every choice and every non-choice. We don’t have to be a function of other people’s behaviour. We don’t have to do what everyone else is doing. We don’t have to do what we’ve always done in the past.