This story is interesting to me because of the year it was written. As a modern parent, I hear a lot about how ‘parents these days’ are overprotective of our children, interfering too much in their lives, stunting their emotional development. Yet this is a story of one such mother, and it dates from 1952. Have mothers (in particular) always been accused of ‘helicopter parenting’, forever walking that invisible line between caring too much and not caring enough?

WHAT HAPPENS IN “A DAY LIKE ANY OTHER”

Two girls (perhaps aged 7 and 8) upset their governess by telling her their father has died in order to break up the monotony of their day. The father is actually in hospital, with a condition doctors can’t diagnose.

SETTING

Although the Kennedys keep moving from country to country (experiences you’d think would be quite different) each day is essentially the same, revolving around the father’s stomach complaints then basing themselves in pensions near whatever establishment happens to be treating it. The reader is told in the first paragraph about the view outside the window (which includes The Rhine). The masterful thing about this description of place is that it manages to tell the reader where the story is set (to get that ambiguity out of the way) while also showing us a view through the daughters’ eyes, introducing them as ordinary kids eating an ordinary breakfast.

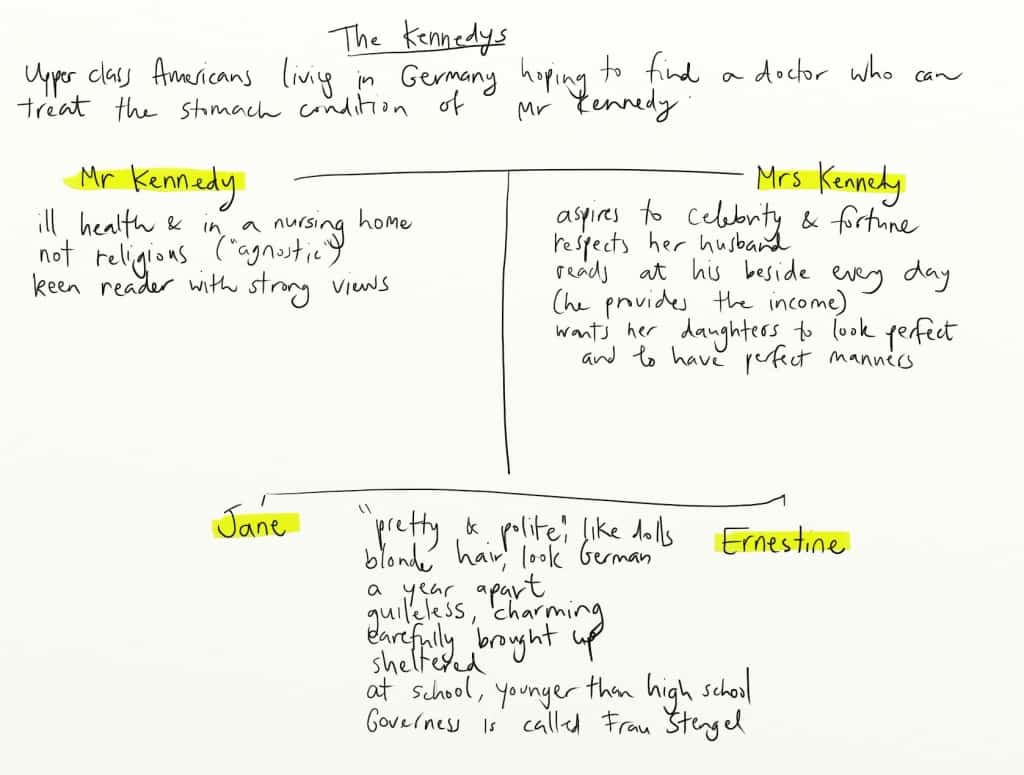

CHARACTERS

Mavis Gallant likes to create married couples who are quite different. By exaggerating their differences by maybe 10 percent more than in real life, the reader is helped to notice character quirks and how these quirks support the theme.

Although Mr and Mrs Kennedy get on fine as a married couple, it’s clear that they have very different attitudes towards their own role as parents. Perhaps typically for his era, Mr Kennedy has little to do with his daughters, explaining to his wife that they’re not at ‘an interesting age’. Mrs Kennedy wonders when they will be at an interesting age. It is mentioned several times in the story that the girls are too young for boarding school, which suggests that they will be packed off out-of-sight as soon as possible, if only boarding school wouldn’t expose them to the wider world.

It is significant that the daughters in this story are indistinguishable from one another. We are told that they are a year apart, but not who is the elder. The reader is offered no information which would distinguish Jane from Ernestine. The reader does learn that acquaintances and strangers refer to the girls as perfect little ‘dolls’. This is the image that Mrs Kennedy strives for. Details delivered by the narrator tell the reader that in fact these are two ordinary children. Although they look like dolls, they are inclined to get grubby and their table manners need work (‘…making whirlpools in her porridge with her spoon’). Sometimes this ordinariness is conveyed by a single word: ‘They abandoned their slopped glasses of milk’; other times we are given more:

“There’s milk all over your mouth, and Ernestine’s hands are filthy. Do you want to make my life a trial?”

We are also told early on that the girls are not old enough to have perfected their theory of mind: ‘It did not enter her head that her mother knew what snow was like.’ This prepares the reader for the innocent lie that comes later.

Mrs Kennedy doesn’t always succeed in maintaining her vision of her own daughters as little Renoirs. In their bedroom, at the end of the story, she finds them together in bed and thinks they look quite ‘ordinary’.

Their governess, Frau Stegel, is the only other rounded character in this story. She is almost a caricature, but a very recognisable one all the same. Have we all known a teacher who is too emotional for their own good, or who doesn’t know they’re being manipulated by their students?

The children were much too pretty to be taxed with lessons. Frau Stengel gave them film magazines to look at and supervised them contentedly, rocking and filing her nails. She lived a cozy, molelike existence in her room on the attic floor of the hotel, surrounded by crocheted mats, stony satin cushions, and pictures of kittens cut from magazines.

THEME

This is a story about sameness/monotony and about blindness/ignorance.

For this story, the theme of sameness/monotony is conveyed first via the title. The first paragraph, too, creates a world of entrapment:

Jane and Ernestine were at breakfast in the hotel dining room when the fog finally lifted. It had clung to the windows for weeks, ever since the start of the autumn rains, reducing a promised view of mountains to a watery blur.

The hotel brochure has ‘promised’ a nice view from the window. Similarly, the Kennedys have moved to Germany on the ‘promise’ (or hope) that Mr Kennedy will find a doctor who can help him. Living in fog sometimes feels as if you are surrounded by walls, unable to see very far. This is how it can feel to be a child, unable to see the situation fully as an adult can, trying to piece together what’s happening in a family with limited information. Because there are two girls, they can feed off each other, with the older one not sufficiently old enough to explain things to her younger sister. Mrs Kennedy shields her daughters from the world, refusing to let them even see a movie. She doesn’t even tell them that their governess is expecting a baby, afraid that the girls will ask her to explain the finer details of sex. To the daughters, the whole world is a ‘watery blur’, and so the reader excuses them for wanting to spice up their insular lives just a little bit by telling Frau Stengel that their father is dead.

Frau Stengel herself is another example of a character who is insulted, with her ‘mole-like existence’ and ‘pictures of kittens’. The baby inside her is a further extension of living in the comfort of a womb. Frau Stengel is oblivious to the real dynamics operating between herself and the two lovely little girls. But the reader is told:

“We like you, Frau Stengel,” Jane had said once, meaning that they would rather be shut up here in Frau Stengel’s pleasantly overheated room than be downstairs alone in their bedroom or in the bleak, empty dining room. Frau Stengel had looked at them and after a warm, delicious moment had wiped her eyes.

The themes of sameness and blindness are related, since a monotonous, sheltered life in which each day looks exactly the same ultimately leads to the blindness and ignorance. The irony of this story is that although Mrs Kennedy goes to great lengths to nurture her daughters’ minds, going so far as to employ a governess rather than send them to the local Catholic school, it is the girls’ very ignorance which is just starting to lead to some unpleasant behaviour. Mrs Kennedy’s assessment of her daughters at the end of the story (not beautiful, just ordinary) suggests that this may only be the beginning of the lack of empathy which comes from overprotection. Alternatively, Mrs Kennedy may have just had an epiphany, and realise that because her daughters are ordinary they should have a more ordinary life. Readers are left with the invitation to judge Mrs Kennedy, and decide what we would do ourselves if we were in her position.

STRENGTHS OF NOTE

The wonderful advantage of an omniscient POV is that the writer can reveal information of which the character is not aware. Mavis Gallant says a lot about a character via small details:

“I have been told that they resemble little Renoirs,” Mrs Kennedy had replied, with just a trace of correction.

We learn that Mrs Kennedy is concerned with appearance, and also likes to be right. (Though she does defer to her husband, who is far more like that.)

Their charm, after all, was not entirely the work of nature; one’s character was just as important as one’s face, and the girls, thanks to their mother’s vigilance on their behalf, were as unblemished, as removed from the world and its coarsening effects, as their guileless faces suggested.

The small irony here is that although Mrs Kennedy knows that ‘one’s character’ is just as important as one’s appearance, it’s all one and the same, really, because Mrs Kennedy wants the girls to develop ‘good character’ so that they appear to the world as she thinks they should. While telling herself she’s not shallow, she demonstrates that she still is.

There is humour in this story, delivered dead pan:

A weaker man might have given up and pretended he was better.

The fog is used as an extended metaphor to show the lack of vision of the characters. At times the ‘fog’ even comes from outside and affects what’s going on within:

Frau Stengel’s favourite music curled around the room like a warm bit of the fog itself.

Another masterfully chosen metaphor compares the little girls lying in bed as ‘two question-marks’; these are two little girls who should be full of questions about the world, but they are not. They seem content with their cutting and colouring and chocolate biscuits. Perhaps it is the questioning of childhood which Mrs Kennedy finds so repugnant, and leads to her thinking of her sleeping girls not as special but as ordinary. She may also be wondering what will become of them. Wishing for grandiose weddings and glittering marriages, she must at times wonder if her dreams for her daughters will play out.

STORY SPECS

Approx 6200 words

Published 1952

Via the omniscient POV which sometimes zooms in to reveal the state of mind of the daughters, the reader is reminded what it feels like to be a child:

Down below, on a flat green plain, were villages no bigger than the children’s cereal plates.

The readers know that this perception is simply a matter of distance, size and perception, but we are reminded of how it feels to see the world through a child’s eyes. To the girls, the villages really are the size of plates. “You can see everything,” says one of the girls of the mountains in the distance. Her world is so insular that perhaps she does mean ‘everything’ in the literal sense. This is the kind of detail which stands out on a second reading.

The girls had no idea who Hitler was.

…they ate chocolate biscuits purchased from the glass case in the dining room… (The girls needn’t bother themselves with how the biscuits really got there, or who made them, or who paid for them.)

Found in the collection The Cost Of Living, with an introduction by Jhumpa Lahiri.

COMPARE WITH

Sun and Moon by Katherine Mansfield, for a short story about adults who are disconnected emotionally from their own children, caught up in each other and in their own adult world.

WRITE YOUR OWN

A teacher/tutor you once had, unremarkable except for perhaps one thing

An incident that happened in class, in which the teacher didn’t fully understand the social dynamics of the classroom

A married couple who have managed to work out an amiable living arrangement despite being quite different

A time you lied/exaggerated as a child, before you realised the wrongness of it