“A Complicated Nature” is a short story by William Trevor, published in Angels At The Ritz And Other Stories (1975). Find it also in Collected Stories.

A prim, starchy man who lives alone in his apartment faces a moral dilemma when the woman upstairs calls him, begging for a favour. She wants him to help shift a man’s body so it doesn’t look like he died during sex. This woman has been having an affair.

TECHNIQUES OF NOTE

UTILISING HEARSAY

At a party once Attridge overheard a woman saying he gave her the shivers.

opening sentence of “A Complicated Nature”

Reporting hearsay gives more weight to a description, which otherwise comes from an unseen narrator, and may be unreliable. Later, the narrator reminds us that Attridge’s ex-wife called him a ‘nasty, dry old thing’.

RECREATING SHOCK IN THE SHIFT TO SINGULATIVE MODE

Stories written in the old-fashioned way start out by describing setting and character (iterative mode) before launching into what happens on this particular day. The switch happens when the author writes something like, “But one day…” (There are many more sophisticated takes on this.)

William Trevor describes Mr Attridge, we make our minds up about him, then Mr Attridge is startled by a phone call. But Trevor does not tell us the phone rang. He shifts with the following sentence:

‘I’m hopeless in an emergency.’

“A Complicated Nature”

This sentence discombobulates the reader. Who is saying this? Why is he saying this? I had to read it several times myself. This is deliberate, of course. This is William Trevor recreating Mr Attridge’s discombobulation for the reader.

SETTING OF “A COMPLICATED NATURE”

PERIOD

1970s. An afternoon in late November. Raining at half-past three. Twilight has set in.

DURATION

Counting singulative mode (not the life which led up to it), the story takes place in maybe twenty minutes?

LOCATION

An apartment block. Mr Attridge lives five storeys up.

ARENA

Between the apartments of Attridge and Mrs Matara, who lives in the rooms one storey up. It’s quicker to take the staircase than the elevator to get from one apartment to the other.

MANMADE SPACES

The apartment block. William Trevor gives us a detailed description of the man’s home. Notice how he weaves character and backstory into description. What do you think Trevor means readers to take away from this detail? (How are we to judge him?)

Attridge lived alone now, existing comfortably on profits from the shares his parents had left him. He occupied a flat in a block, doing all his own cooking and taking pride in the small dinner parties he gave. His flat was just as his good taste wished it to be. The bathroom was tiled with blue Italian tiles, his bedroom severe and male, the hall warmly rust. His sitting-room, he privately judged, reflected a part of himself that did not come into the open, a mysterious element that even he knew little about and could only guess at. He’d saved up for the Egyptian rugs, scarlet and black and brown, on the waxed oak boards. He’d bought the first one in 1959 and each year subsequently had contrived to put aside his January and July Anglo-American Telegraph dividends until the floor was covered. He’d bought the last one a year ago.

“A Complicated Nature”

STORY STRUCTURE OF “A COMPLICATED NATURE”

SHORTCOMING

It was true, and he admitted it to himself without apology; though ‘sharp’ was how he preferred to describe the quality the woman had referred to. He couldn’t help it if his quick eye had a way of rooting out other people’s defects and didn’t particularly bother to search for virtues.

“A Complicated Nature”

On reading this, I flesh-out a character who is hard on other people and probably also holds himself to exacting standards as well.

William Trevor is very clear about the man’s weaknesses, pointing it out directly rather than asking us to fill in all the gaps: ‘Vanity was a weakness in him.’ (Modern writers might consider this telling not showing, or telling on top of showing.)

DESIRE

This is not a man who wants anything. He’s happy in his world and receives a call to action. He does not want to get involved. To move a dead man would make him an accessory to something, maybe even a crime, and we already know he holds himself to high standards.

OPPONENT

Mrs Matara.

When it turns out the lover is not dead after all, they band together as a single unit and Mr Attridge is a very reluctant third wheel to something, with information he’d rather not have about his neighbour, or about anyone.

This story involving Mrs Matara and the supposedly dead lover frames the story of Mr Attridge’s short-lived marriage. to Bernice Golder. The link is that his wife and Mrs Matara are both Jewish women.

This is where the story feels a bit cringe to a modern audience. Surely, even to a 1970s audience, we think of Adolf Hitler, who infamously hated Jewish people supposedly because his ex was Jewish.

Also, I’m not sure if this is a contemporary problem for writers, but readers sometimes mistake racism of a character for racism of the author who created the racist character. Adam O’Fallon Price at The Millions writes this:

The bigotry is nonetheless unpleasant and feels somewhat recklessly tossed in.

The William Trevor Reader: “A Complicated Nature”

Which raises the question: When is it okay to write a racist character? Do stories require a particular set-up before it is justified? As it stands, William Trevor makes both women Jewish to explain to readers part of why he does not like, or want to help, his Jewish neighbour years later.

Note that Adam O’Fallon did not feel the same unpleasantness when reading about the culture of misogyny exemplified in “Mrs Silly“, even though both stories contain oppression as their backdrop. Perhaps the key is this: When writing about oppression, weave and weft it at all levels of the story. William Trevor treads more dangerously here. He has written a story that is not about antisemitism, but anti-Semitic sentiment issues forth from the main character. This seems to be the level at which readers wince and wonder if this is the author’s anti-Semitism peeking through. (More of a problem when readers are new to an author’s work, of course.)

PLAN

Mrs Matara needs a man to help her move her lover’s body from her marital bed to anywhere else, so her husband doesn’t come home and know she’s been cheating on him.

Attridge resists, and keeps resisting.

THE BIG STRUGGLE

Two threads of conflict:

The pleading Mrs Matara and the former Mrs Attridge, who accuses her new husband of ‘not liking women’.

ANAGNORISIS

The ‘twist’, of sorts, is that the lover isn’t dead at all. The emotional twist, building on that: Attridges wishes he was dead, now. A comical turnaround, since he was concerned with being implicated in the death of a man.

Answer honestly: Did you initially read Mr Attridge as a gay man? He takes a keen interest in interior decor. He spends holidays with an older woman friend. Most of all, his former wife accused him of being ‘dry’ and of not liking women.

It’s easy to confer gayness, but that’s not what William Trevor tells us at all. Instead, he has perfectly described a person we’d now say is on the asexual spectrum:

The love [his ex-wife] sought would have come in its own good time, as sympathy and compassion had eventually come that afternoon.

“A Complicated Nature”

William Trevor has described demisexuality, about forty years before the word existed to describe it.

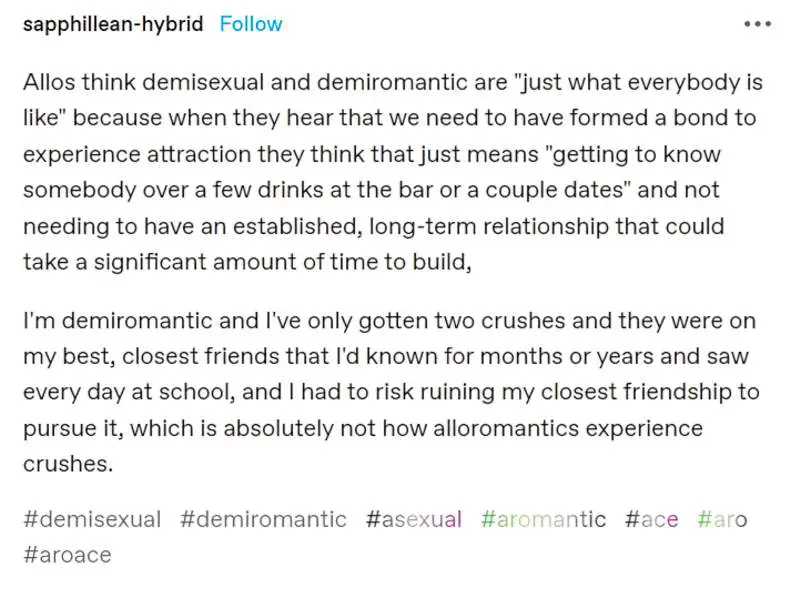

Demisexuality: Feeling sexual attraction to someone only after forming an emotional bond with them. Demisexuality differs from allosexual attraction because allosexuals can feel attraction for strangers, new acquaintances and celebrities. For some allosexuals, some kind of interaction must take place before attraction kicks in, but demisexuals are much further down that path. Attraction might take years to develop.

Without the asexual reading, “A Complicated Man” looks like a simple ‘Bitter man blames women for everything’ story, which wouldn’t impress me much.

Attridge wanted to say something. He wanted to linger for a moment longer and to mention his ex-wife. He wanted to tell them what he had never told another soul, that his ex-wife had done terrible things to him. He disliked Jewish people, he wanted to say, because of his ex-wife and her lack of understanding. Married repelled him because of her. It was she who had made him vicious-tongued. It was she who embittered him.

“A Complicated Nature”

But with William Trevor’s complexity, it now an exploration of sexual consent within marriage, which is far more rare and interesting because the demisexual partner is a man, not a woman (as is stereotypical).

There are two kinds of freedom: freedom to and freedom from.

Ace: What Asexuality Reveals About Desire, Society and the Meaning of Sex by Angela Chen

In her book, Angela Chen advocates the consent framework proposed by Emily Nagoski, outlined in Come As You Are. You may already be familiar with Nagoski’s category of sexual consent:

- Enthusiastic

- Weilling

- Unwilling

- Coerced

Nagoski’s framework is more nuanced than “No means no”, which is insufficiently nuanced. Chen adds:

Unlike models that emphasize enthusiastic consent (“yes means yes”), it doesn’t imply that aces who can’t give enthusiastic consent are unable to consent at all, which would wrongly place us in the same category as children and animals. It expands the “yes means yes” slogan by pointing out all the possible varieties of yes. […] For aces who do have sex, the difference between willing and unwilling is not one of action but one of intention and agency.

Ace: What Asexuality Reveals About Desire, Society and the Meaning of Sex by Angela Chen

William Trevor’s story precedes any of this discourse by decades. Sure, women’s lib was happening, but it skipped men such as Mr Attridge. In the 1970s, gender and sex were binary, everyone was heterosexual or illegal, and men who weren’t interested in sex at the drop of a hat were considered broken. Regarding Trevor’s contemporaneous readers, I doubt many would have considered a gay reading for Mr Attwood. For conservative folk living typically sheltered lives, gayness was a taboo and shameful thing which happened in the seedy alleyways of faraway towns. Even when your uncle/cousin was clearly sleeping in the same bed as another man, that’s not because he was gay. Oh, no. They were just very close friends.

NEW SITUATION

Long after Mr Attridge’s marriage has ended, this strange encounter with a pleading Jewish woman has made him realise something: He understands where his anti-Semitism comes from, and the depths of the damage done to himself by his former wife and her sexual coercion.

EXTRAPOLATED ENDING

I have extrapolated that the wife coerced him into having sex. (Emily Nagoski’s number three or four.) This pressure (which would be on the rape spectrum) has caused him long-term damage.

However, I expect this self-awareness will prove helpful to Mr Attridge moving forward.

RESONANCE

We are currently in an era when many people doubt the validity of labels such as demisexuality, insisting these identities have been made up by Gen Z for attention. Yet as soon as the experience is described using other words, or explicated in a story like this, no one dismisses the experience. Now it makes sense. Of course some people are like that. Humans are wonderfully varied.

When it comes to decoding unnamed queerness of fictional characters, readers are still inclined to stick with a gay reading, forgetting there are other kinds of queer. Bisexuality and asexuality remain largely invisibilised.

For an egregious example of queer illiteracy, Edward Gorey’s biographer has no idea what asexuality means despite using the word over and over. (He also doesn’t see genderqueer when it whacks him in the face).