“A Blaze” (1911) is a short story by Katherine Mansfield, included in her German Pension collection. This is a story about a dynamic Japanese people might describe as amae.

OPENING WITH DIALOGUE

Mansfield often started her stories in medias res, but “A Blaze” stands out against most because it opens with a four exchanges of dialogue, sans dialogue tags, written almost as if it were a movie script. These paragraphs of dialogue tell us quite a bit:

- Two men called Max and Victor are outside playing on a slide. At first I thought they were at a playground, but I think they’re talking about a natural incline where it’s possible to slide down. Max is going down the slide in a non-conventional, dangerous manner which might mean he’s reckless, but also might mean he’s a bit un-co. He appears to have a childlike sensibility.

- It is cold, Max is especially wet. Now it is revealed that Max has been playing by way of getting into shape (not because it’s pure, childlike fun).

- They are smokers, they drink coffee at the Club House, they are in no hurry to be somewhere doing something useful. They also talk to Forman as if they consider him a lesser human being than they are: “Here, Forman, look after this sleigh…” In short, they belong to the leisure class.

- It’s misty, there’s heavy snow on the ground and people are getting about on sleighs.

- They are in Germany (A “Fraulein Winkel” walks past, but we probably already knew this because of the title of the collection).

- “That’s the worst of this place” tells us these men are not natives to the area. They’re here for a short period of time.

SETTING OF “THE BLAZE”

- Germany

- The Wald See means forest lake in German

- Winter (a record dump of snow covers the ground, creating excellent sledding conditions)

- Misty — Is this just a detail to evoke a scene, or is the mist symbolic? What are these men failing to see?

- Early 1900s

- Late afternoon then early evening

- A coffee house which is probably a little on the cold side for comfort (that’s why the men are so keen to sit near it). This proves ironic because the title is about a ‘blaze’ (of passion). Max feels cold but his emotions burn.

- These non-Germans don’t approve of German food, with cake like “underdone india-rubber” (a word you don’t hear much these days, probably because things once made of india-rubber are now made of different polymers).

CHARACTERS AND THEIR DYNAMICS

Max

Bums a cigarette off Victor. (People used to share them more frequently in those days, like you would a packet of biscuits.) More than Victor he is feeling the cold. Is the guy who’s bossy to the person in charge of dealing with the sleighs. Max half turns his back to Fuchs and Wistuba, ostensibly to warm himself by the heater but this is always interpreted as the cold shoulder. The other men talk — Max withdraws from the conversation.

Victor

More careful than Max. Not as free-spirited, or perhaps not such a show off. Judgmental of women, we assume, since he passes judgement on a woman passing by, suggesting he thinks it’s his job to offer his view of women for others to take in: “Damned elegant”. Has a little brown dog called Bobo. Victor says, “What’s the matter, my dear?” showing that the dynamic is for Victor to joke that he is romantically in love with his friend, Max. He also jokes in a way that suggests a dynamic described best by a Japanese word, amae.

Max And Victor Together

Max and Victor have an interesting relationship, especially for the era, I think. Today it’s common for young men to jokingly address each other as if they are lovers. (This can be #nohomo ‘humour’ and possibly problematic in a homophobic regard.) These men in Mansfield’s story seem to be playing a role, or making a joke out of playing a role: Victor calls Max ‘dear’ and says that he will look after him, under the (jokey) assumption that Max is sulking to garner his attention.

Japanese culture has a class of words we don’t have in everyday English to describe this dynamic, and has in the past been seen as a uniquely Japanese aspect of psychology.

In 1973 a psychologist called Takeo Doi published a book called (in English) The Anatomy of Dependence. Doi saw the amae dynamic as a positive aspect of Japanese culture, describing it as an interaction in which one person lightheartedly triggers another person’s emotional warmth and acceptance.

Subsequent psychologists have critiqued this unilateral view of the amae dynamic and recognise two distinct functions. One is prosocial, the other not so much:

- To fawn dependency in order to strengthen a bond. “Pick me up, mummy!” That kind of thing.

- To ask something of someone with the expectation that you will be obliged.

Psychologists have studied similar phenomena in the West. Most of us are familiar with the Benjamin Franklin Effect: The act of doing a favour for someone else makes the person performing that favour feel more generously towards the person who asked. By carrying out a favour for someone else we persuade ourselves that if we are doing them a good turn we must like them. Con artists make the most of this effect. Beware the Joe Blow in the street who asks you to hold their wallet. They may be about to do the dirty on you. In general, though, the Benjamin Franklin effect might correlate to the prosocial side of the amae dynamic.

As for the dark flip side, an NPR Hidden Brain podcast called “The Influence You Have” describes the infamous 1960s Yale experiment which asked volunteers to submit actors to pain by pushing a button. Disturbingly, a huge proportion of volunteers did as they were told, believed their victims were inflicting massive pain, but caused pain regardless.

A more recent study adds to this older one by asking what few had considered before. Whenever we hear about that old experiment we wonder if we’d be one of those volunteers delivering shocks, automatically putting ourselves in the shoes of the volunteers. We don’t naturally put ourselves in the shoes of the researcher, who is asking volunteers to administer the shocks. This has led to the following insight:

Psychologists say we are often consumed with our own perspective, and fail to see the signs that others are uncomfortable, anxious or afraid. Vanessa Bohns, a professor of organizational behavior at Cornell University, says researchers refer to this phenomenon as an “egocentric bias.” This bias may reveal itself when we put others on the spot, like when we ask a co-worker out on a date or solicit a stranger for money. It causes us to vastly underestimate the pressures we place on those around us, and it can have all sorts of serious consequences.

The Influence You Have: Why We Fail To See Our Power Over Others

This is similar to the dark side of the amae dynamic: When we ask others for things, we underestimate the power we have over them. This has huge implications, especially when a more powerful member of a group asks something of a less powerful member.

But Max and Victor are equals, as far as we know.

“Baby doesn’t feel well,” [Max] said, feeding the brown dog with broken lumps of sugar, “and nobody’s to disturb him — I’m nurse.”

Perhaps it is by complete coincidence that the Japanese words around this concept come from the Japanese word ‘sugar’ and that in Mansfield’s story Victor is feeding his own dog pieces of broken sugar lumps as he ‘fawns over’ his unwell friend. How much reading had Mansfield done on Japanese psychology? If she’d read about it, what exactly had she read? (As far as I know, the West wasn’t talking about this until Doi published his book in the 1970s.)

On the other hand, sugar is a universal symbol and apart from that basic meaning of ‘sweet tasting’, people from vastly different cultures might apply it in the same way to interpersonal dynamics by coincidence, because it simply fits. A Westerner who has never heard of the Japanese concept of amae might independently say that Victor is treating Max in a sugary way.

Fuchs

A German name meaning ‘fox’. I’m not sure this is symbolically relevant. Fuchs is the first to show concern for Max, who has withdrawn. Both Fuchs and Wistuba function mainly to get Victor out of the way for Max and Elsa’s scene together.

Wistuba

A German name. Witsuba’s observation tells us more about Max:

“That’s the first time I’ve ever known him off colour,” said Wistuba. “I’ve always imagined he had the better part of this world that could not be taken away from him. I think he says his prayers to the dear Lord for having spared him being taken home in seven basketsful to-night. It’s a fool’s game to risk your all that way and leave the nation desolate.”

Wistuba thereby reveals himself as a Christian man, or at least someone well-schooled in Christianity. I think the seven basketsful is a Bible reference. From what I can gather, Mark 8:1-9 describes the time Jesus miraculously fed a crowd of 4000 people following him about for three days. They’d had nothing to eat. They were walking West of the Sea of Galilee, which is desert.

Jesus asked his disciples how many loaves they had with them. They had seven. Jesus told the crowd to sit down, then fed 4000 people bits of broken-off bread until they were satiated. Even after he’d done so, there were seven baskets of bread bits left over.

Is Wistuba astute enough to see that Max is a broken man (like the broken bread)? I don’t fully fathom the insult that Witsuba delivered to Max, but Max snaps back, indicating that Witsuba is either much younger or much older than them and should be wheeled about the snow in a pram. (I’m going with much older because of Wistuba’s complex, veiled insult.)

Elsa

Viktor’s wife. Mansfield uses the technique of mentioning a character before she ‘enters the stage’. (We wonder about her, and are then glad to meet her.)

She ostensibly hurt her head sledding with Max on the Sunday and is staying at home. Victor has told her he’ll be home early evening but now he’s out with the lads he changes his mind. He doesn’t want to tell his wife himself that he’ll be late so asks Max to tell her for him.

Mansfield introduces Elsa as a society lady whose full-time job is to look pretty and act coquettishly. She is reading a fashion magazine, has a box of creams beside her (I assume face creams, not some kind of food), and she mentions her new dress to Max as if it’s important to him (as it clearly is to her).

Max And Elsa Together

Now Mansfield provides us with a different manifestation of the amae dynamic. Max describes it in full as he accuses her, revealing to us that he wasn’t miserable earlier because he was wet and cold; he is miserable because he is love sick:

“Do you suppose that when you asked me to pin your flowers into your evening gown—when you let me come into your bedroom when Victor was out while you did your hair—when you pretended to be a baby and let me feed you with grapes—when you have run to me and searched in all my pockets for a cigarette—knowing perfectly well where they were kept—going through every pocket just the same—I knowing too—I keeping up the farce—do you suppose that now you have finally lighted your bonfire you are going to find it a peaceful and pleasant thing—you are going to prevent the whole house from burning?”

Note that all this backstory comes via an argument, which is a trick often pulled by writers. Normally, in pleasant conversations, people don’t go into a whole lot of backstory. Put them in conflict, however, now all the old wounds come out, and emerge perfectly naturally. If you want to show the reader conflict via backstory in dialogue, put it in an argument. (Actually, once you start noticing this you see it done all the time on TV and it’s a bit annoying.)

What has Elsa been up to? She has been flirting outrageously with her husband’s friend, creating a flirty variation on the amae dynamic: She expects this fun to have no effect on the sexual object, ie. Max.

Max, for his part, has not seen the dynamic for what it is: Flirting constrained by the social construction of monogamous marriage.

Mansfield’s story encourages the reader to ask: Who is responsible for Max’s misery? If a woman flirts with a man, what does she think will happen?

I deliberately use the language of victim blaming in that sentence. Our rape culture regularly asks women who were out late at night/drunk/alone/wearing women’s clothes etc. “What did she think would happen?”

Here’s where I fall: Max is responsible for managing his own feelings. He had every right to ask Elsa to stop. At that point she needed to have stopped. We don’t have that particular backstory because Mansfield writes her characters in statu nascendi (without much in the way of back story), but it appears as if Max has been going along with all of this and now he suddenly explodes.

When Max talks about the ‘spider-and-fly business’ he is alluding to “The Spider and the Fly”, a famous poem by Mary Howitt. This spider traps a fly by drawing her in with flattery. The poem has more recently been illustrated by Tony Diterlizzi.

The poem functions as a cautionary tale to young women, who are not to be drawn in by wily, flattering words. The assumption is that women are easily flattered by being told they are pretty, and will sleep with any man who tells her so.

Here Mansfield flips the gender of this gendered narrative: Max considers himself the fly, Elsa the spider drawing him in. (Mansfield also flips the gender of a highly gendered narrative in “Poison” — poisoning in stories is femme coded, but the newspaper poisoner in that story is gendered male.)

He uses another strange phrase too, and Mansfield seems to have coined it:

You only love Victor on the cat-and-cream principle—you a poor little starved kitten that he’s given everything to, that he’s carried in his breast, never dreaming that those little pink claws could tear out a man’s heart.

Like the young man in “Poison”, Mansfield paints Max in hopelessly melodramatic terms. He throws his arm across his face while facing the window (a la Days of our Lives), he buries his head in her lap, he explains how he loves her and wants to kill her. (Lest we forget: love is not the opposite of hate. Indifference is the opposite of hate.)

Max then accuses Elsa of lying, because in the solipsistic fashion we might expect of a melodramatic man, he assumes that if he is in love with Elsa then she must be in love with him; anything else must be lying, because here’s another dominant narrative: Women lie all the time. Notice at this point that Mansfield has earlier emphasised the ways Elsa has ‘drawn Max in’ with her feminine wiles — drawing attention to her clothing, her cosmetics. Feminine accoutrements are often considered forms of feminine ‘lying’, because they are regarded as a kind of mask (worn by people who wish to be more beautiful than they ‘really’ are).

When Max tells Elsa she is ‘heathenishly beautiful’ he is making use of a common conversational device we might call a transferred epithet: It’s not Elsa who is the ‘heathen/sinful/lustful’ one; he is transferring his own emotion onto her a la ‘miserable weather’.

Max’s nature is finally revealed to the reader (confirmed, hopefully) when he accuses Elsa of being ungenerous, comparing her unfavourably to a prostitute, on the assumption that a prostitute is lowest of the low.

Elsa agrees with him, but immediately asks, “Are you going?” She is clearly agreeing with him to get rid of him. This is now a dangerous situation for her, not because he might strike her (though he has revealed his conflation of sex and murder), but because she has a conventional, safe marriage to Victor.

Elsa and Victor Together

After a jump cut, Victor comes home and Elsa gives him half the story: Max was here and was “frightfully boring”.

The penultimate sentence confirms my view that this story is a story of the amae dynamic, because as I had fully predicted, the amae is triangulated when Victor and Elsa demonstrate for us the amae dynamic between them. First he says “Poor darling,” then:

She flung her arms round his neck and looked up at him, half laughing, like a beautiful, loving child.

The story could’ve ended there, except Mansfield gives us another paragraph to confirm for us that Max was wrong about their marriage — they are perfectly happy together because this amae dynamic works well:

“God! What a woman you are,” said the man. “You make me so infernally proud–dearest, that I…I tell you!”

Notice what else Mansfield did there? Victor is now ‘the man’. Perhaps Max is half right. By taking Victor’s name away from the sentence Mansfield removes defining qualities. Now, in this moment, any man would do, so long as he catered to Elsa’s need: to be flattered, admired and loved.

In sum:

- Victor amae‘s Max

- Elsa amae‘s Victor

- Victor amae‘s Elsa and vice versa “You naughty boy“

If Max’s angry “blaze” is basically right, Elsa has been using both the prosocial and dark flip side of the amae dynamic: Prosocially with her husband, and darkly with Max, who has not seen the dynamic for what it is. Worse, he has not taken full responsibility for his own emotional responses. At some point in every relationship we decide to dive right in. This is a decision.

I wonder if Mansfield saw the gendered double standard: That women are responsible for avoiding their own sexual entrapment, AND women are ALSO responsible for being the sexual entrappers of helpless men.

Methinks she knew full well.

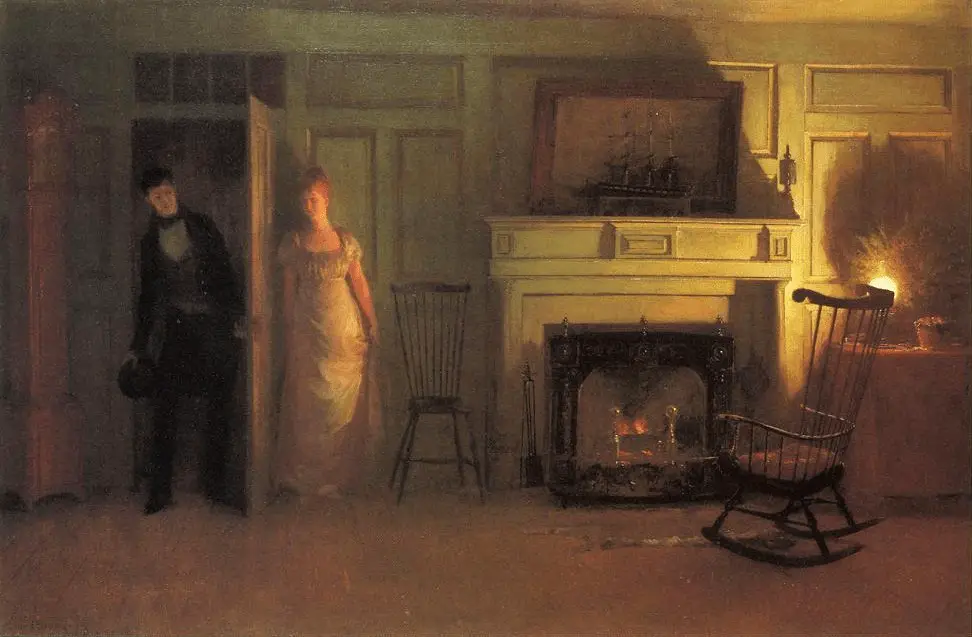

Header painting: William Lipincott – Love’s Ambush