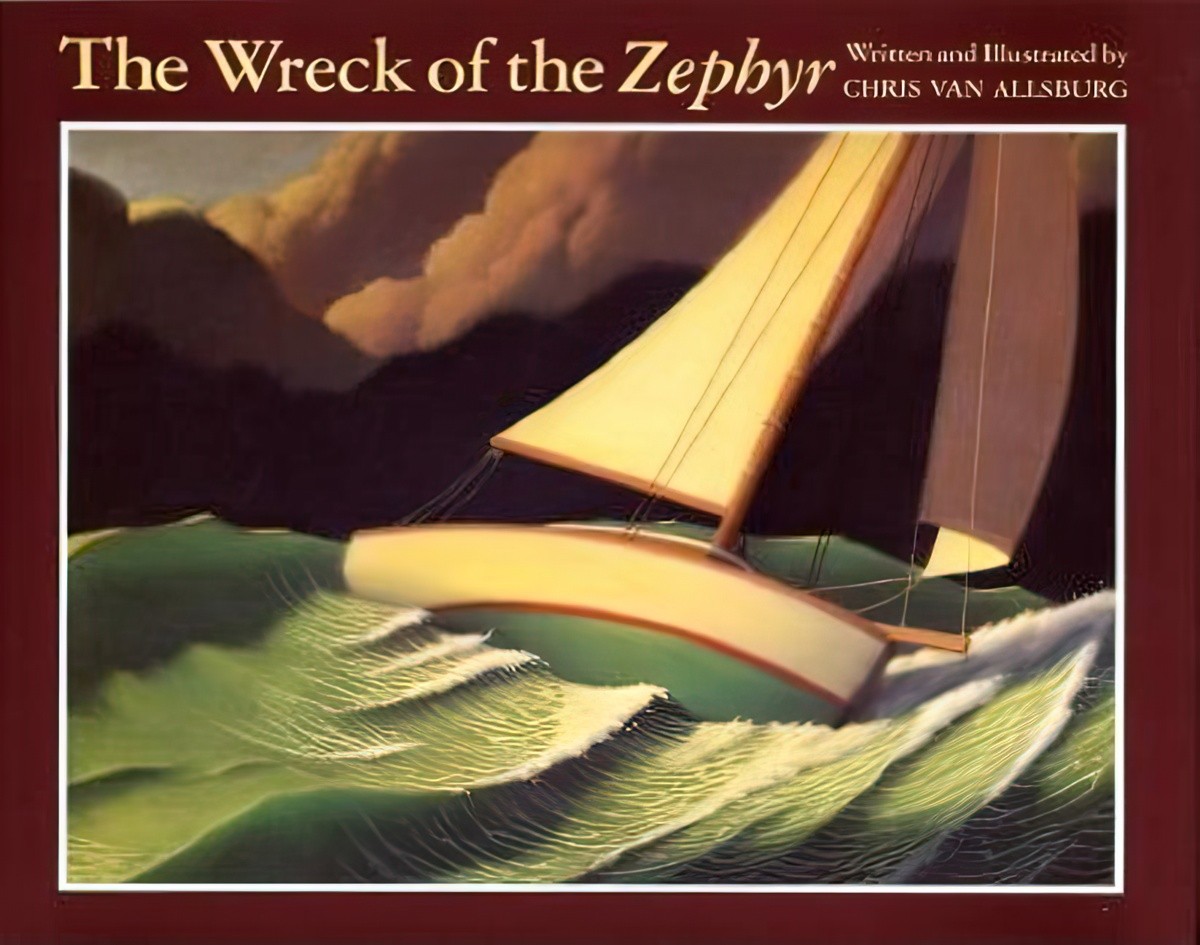

The Wreck of the Zephyr is a postmodern, surreal 1983 picture book by American writer and illustrator Chris Van Allsburg.

You’ve probably heard of Jumanji and The Polar Express, which have been adapted for film. The Garden of Abdul Gasazi was his first. The Stranger features a season personified. The Widow’s Broom is a creepy-ass favourite of mine.

According to the marking copy, the illustrations have been rendered in pastel. This is a popular choice for dream-like picture books. Some of the artwork, particularly those cinematic shots of the sky, remind me of Newell Convers Wyeth (American artist and illustrator) 1882 – 1945.

PARATEXT

In 1983, beloved Caldecott-winning illustrator, Chris Van Allsburg, first invited readers to peer over the edge of a cliff to consider the wreck of a small sailboat. Had a churning sea carried the Zephyr up in a storm? Could waves ever have been so impossibly high? And what of the boy who had believed–dared to chase the wind–no matter where it lead?

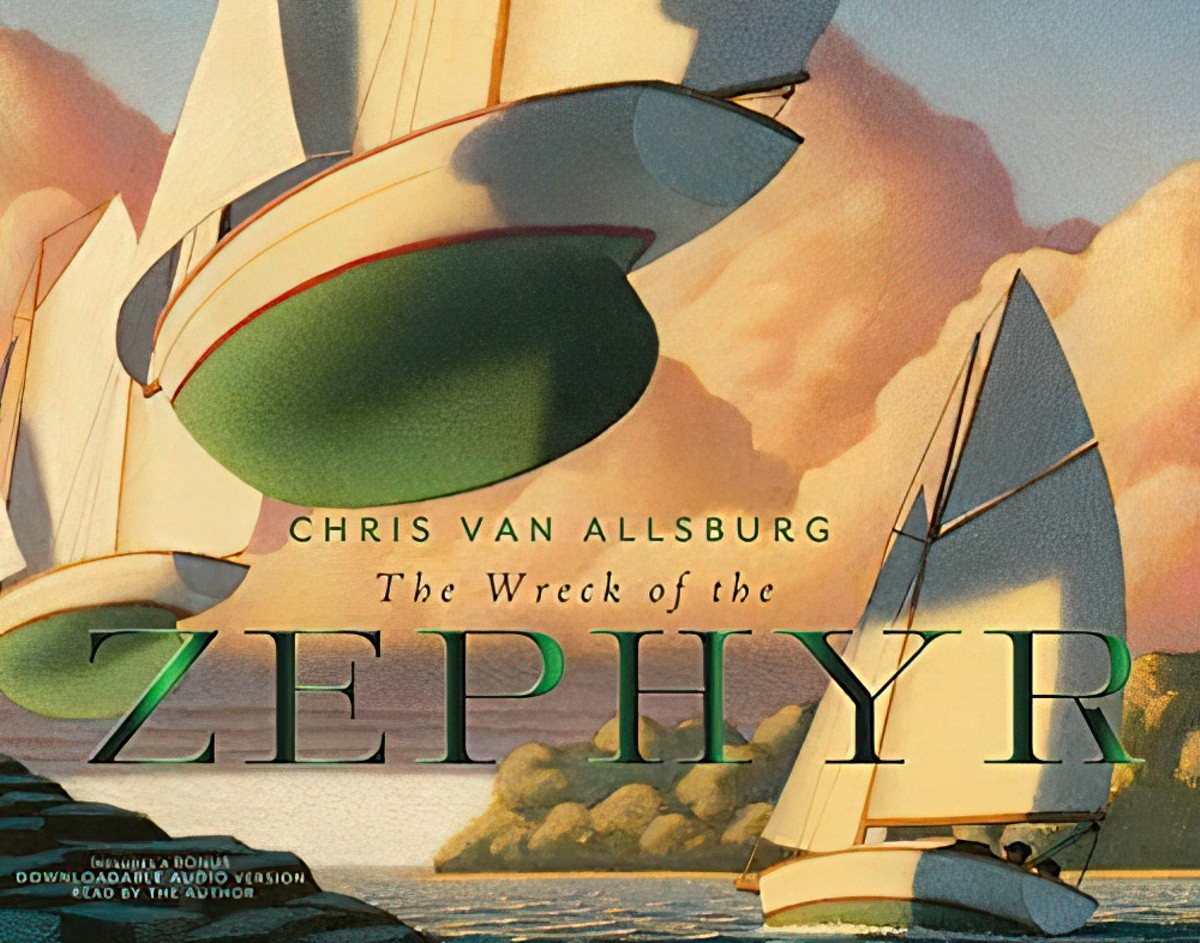

The winds have shifted once again and you’re invited back to the wreck of the Zephyr, to hear the story of the boy and his obsession to become the world’s greatest sailor, and a storm that carried them to a place where boats sail on the wind, instead of on the water.

Told in spare text and haunting, full-colour pastels, Chris Van Allsburg’s spectral sailboats once again take impossible flight. In illustrations so vivid one can feel the whisper of wind and hear the flutter of canvas, depart this world for another to entertain the marvellous possibility of dreams.

SETTING OF “THE WRECK OF THE ZEPHYR”

“The Wreck of the Zephyr” is a timeless story, set nowhere and no place in particular, just somewhere on a coast, with a sandy beach (a magical, liminal space) and a forest.

All of these things have symbolism attached to them, and Chris Van Allsburg makes good use of them all:

- The Symbolism of Altitude (the ship is found on a clifftop). “The waves rose up like mountains.” The story plays with the up-and-down nature of space before the ship is airborne.

- Symbolism of the Ocean versus the Sea (one has depths, one is a flat surface, functioning like a desert). When the boy flies above the sea, he is actually doing a reverse deep-dive into the ocean (but up instead of down). We call space-ships “space-ships” for a reason.

- The Symbolism of Waves, which in this story are not the crashing, terrifying tsunami type of wave, but the gentle, loll-you-off-to-sleep sort of wave.

- Island Symbolism — the boy finds a man, who says he almost never sees strangers on the island. Not only is this a closed-off community, we only ever see a man and a boy in the same place at once, and even then, sometimes it’s only a boy, only a man. Ultimately, this story feels like an allegory for loneliness.

- The Symbolism of Ships

Flight is amazingly common in children’s stories. Floating is a related motif. In children’s books, characters float by: holding onto balloons, levitating by magic or by supernatural means.

Other symbolically similar motifs:

- going up onto a high place, such as a roof or a tree(house) — Andy Griffiths and Terry Denton’s tree house series are mega bestsellers in Australia

- hovering — a subgenre in African-American books

- leaping and jumping — In Laura Ingalls Wilder’s fourth book for children, On The Banks Of Plum Creek, Laura and Mary jump with unrestrained joy off a stack of hay (until they’re told not to by their father). This contrasts with later chapters in the book where the outdoorsy Laura finds it difficult to concentrate in class, where she is required to sit still, restrained like a caged creature.

A ‘zephyr’ is a soft, gentle breeze. Stories about floating (rather than flying) a typically dreamlike, with languorous pacing. This is the sort of book which might put a young child to sleep at night. The beach is a liminal space for the boy in the story, and that time between wakefulness and sleep is the real-world liminal space for the child being read to.

STORY STRUCTURE OF “THE WRECK OF THE ZEPHYR”

“The Wreck Of The Zephyr” is framed by a young boy speaking to an old man on the beach, next to the wreck of a small boat. The boy wonders how it came to be there. The old man spins a fantastic story about a boy who flew it above the clouds before crashing down and breaking a bone.

Although we typically associate ‘carnivalesque‘ with leaping around and making mischief a la The Cat In The Hat, a dreamlike story such as this is a good example of what we might call The Quiet Carnivalesque.

CARNIVALESQUE STORY STRUCTURE OF “THE WRECK OF THE ZEPHYR”

Carnivalesque stories sometimes begin earlier than this one, with an Every Child at home, bored and wishing to have fun, followed by the disappearance or backgrounding of the adult authority figure. In this story, however, the boy is alone by the beach. We can assume all that other stuff took place.

Note, however, that when the boy meets the old man on the island, there has to be some backgrounding of the old man before the boy can learn to fly the boat. Chris Van Allsburg has simply shifted it down a bit.

(It’s amazing how inventive authors are, riffing on the carnivalesque plot type. Every single one is a little bit different, but with the same basic bones.)

APPEARANCE OF AN ALLY IN FUN

Like kids often do, being observant little scientists, the boy finds an odd thing. Soon a man turns up to explain the legend.

HIERARCHY IS OVERTURNED. FUN ENSUES.

Normally a kid wouldn’t be skipping a boat but this kid does. Hence, hierarchy is overturned. But he runs into trouble. He’s whacked on the head with the boom. Which is precisely the reason we don’t let kids skipper boats. Being struck unconscious in a calamity is an unusual turn of events for a picture book, in which very young kids frequently do all kinds of things without risking their actual lives.

FUN BUILDS!

When the kid wakes up on the beach, he has entered a kind of fantasy portal. This is a common trope across all forms of storytelling, including in, say, The Lost Daughter (based on an Elena Ferrante book).

Anyway, ships can float in the sky now. But he has to put in some work before he can get lift-off.

This part of the plot has a very Japanese feel to it. I mean, the whole thing is very Hayao Miyazaki (both men were creating their tentpole stories in the same era — the 1980s). Both men are post WW2 artists, fascinated by ships and (for Miyazaki, at least) planes. But apart from the apparatus, Hayao Miyazaki does not give kids privileges on a plate. They gotta work first. How does Chihiro free her pig-parents in Spirited Away? By weeks of hard-graft in a bath house, demonstrating her capacity for servitude and appeasement of seniority.

The difference is, here the boy says he won’t leave the island until he learns to sail over the waves. The work requirement in Spirited Away comes from above. Van Allsburg’s ideology around working hard is the typically Protestant version whereas Miyazaki’s is the typically Japanese version.

(For another example of Van Allsburg’s Protestant work ethic shining through in his narrative, see The Widow’s Broom.)

PEAK FUN!

Finally, lift off!

Notice how Chris Van Allsburg moves the narrative camera up and down. We get the underside of the boat, and various different high-angle, low-angle, cinematic shots. The language of film comes in useful when talking about the artwork of this author-illustrator.

SURPRISE! (for the reader)

A slightly sophisticated reader may infer that the old man telling the story was the boy, though adult readers may also infer that this old man’s gone a bit loco or is making up a story for a naïve younger audience.

This compression and expansion of time rears its head in the imagery. Remember the old fella pulled out a concertina? In, out, in out, like breathing, like life itself. A life which expands with the addition of memory of story.

RETURN TO THE HOME STATE

If the story had started in the home, it would return there, too. But Van Allsburg has used a different kind of bookend technique: the story-within-a-story, also known as two diegetic levels. (The ‘hypodiegetic’ story is the one about the cray-cray guy who said his ship could fly.)

Notice, too, how the boy is not picture in the first illustration. Only the man. Where is this man being seen from? Floating off the cliffside! Is the boy really even there? Or is this a lonely old man retelling his own life story to an imagined younger version of himself? If so, that would make this your classic repeating story. “Well there’s another tale.”

(Note that I’ve interpreted this story as told by a boy. I’m a hundy percent sure that’s not how I was supposed to interpret it. The narrator is the middle-aged man. I figured a boy would consider a middle-aged man ‘old’.)

“He seemed to be reading my mind.” Could that be because this is really one man’s mind we’re talking about?

Another subtle clue: When he’s flying in the air, the boy wants to ring the church bell to wake everyone up. He wants to be seen flying. The old man has the similar wish to be seen, and may be imagining an audience for himself, even if that audience is only his boyhood self.

For a short story version of this trope, see “Miss Smith” by William Trevor.

What to make of the final image, in which a middle-aged man seems to view an even older man walking away? Well, you probably know my theory. Since this story makes use of fairytale time (not linear, not chronological — sometimes known as ‘mythos’) all ages of the man exist at once.

Not because that’s how time works, but because that’s how we can experience time. Anytime we recall memories, we’re merging the past self with the present.

Of course, a more boring reading is also possible. That middle-aged man is the intradiegetic narratee, not some imagined boy hanging off the side of the cliff.

RESONANCE

The wish fulfilment fantasy of flying/floating in the air will probably never get old. I say this because stories about flying didn’t let up after commercial flying for the masses became a thing.