Possum Magic is a classic Australian picture book by Mem Fox. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BboBeS-vhjg

WHAT HAPPENS IN THE STORY OF POSSUM MAGIC

Grandma Poss uses bush magic to make a child possum (Hush) invisible so that Hush won’t be eaten by snakes. (I’m going to put aside the fact that snakes seem to ‘see’ via vibrations, so an invisibility superpower wouldn’t necessarily protect her…) But soon, Hush longs to be able to see herself again, the two possums make their way across Australia to find the ‘magic food’ (quintessentially Australian food) that will make Hush visible once more. Each year on Hush’s birthday they eat the same food ‘just to make sure Hush doesn’t turn visible again’, thereby creating a kind of mythology about why (white) Australians eat certain foods as celebration.

In case you were wondering just how deep it’s possible to go in the analysis of a seemingly simple children’s story such as this one, Carolyn Daniel has much to say about Possum Magic in her book Voracious Children: Who eats whom in children’s literature. First she points out that this is an example of a Quest Narrative.

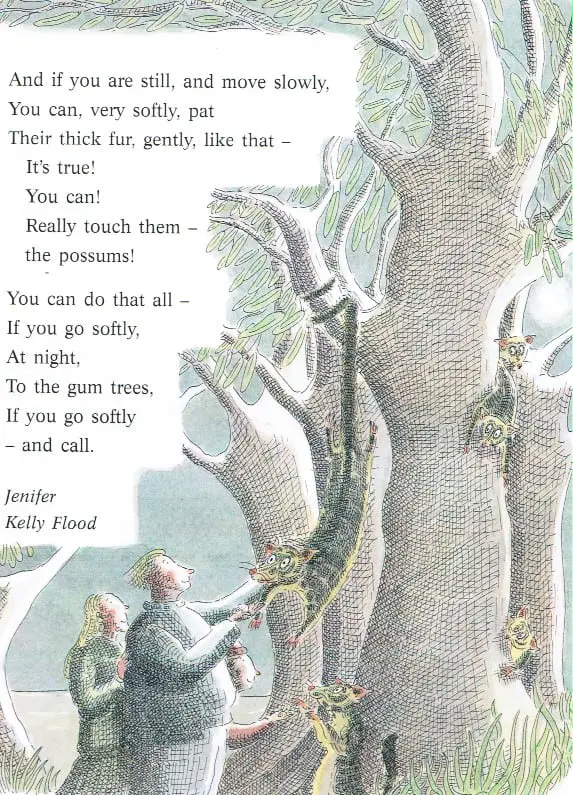

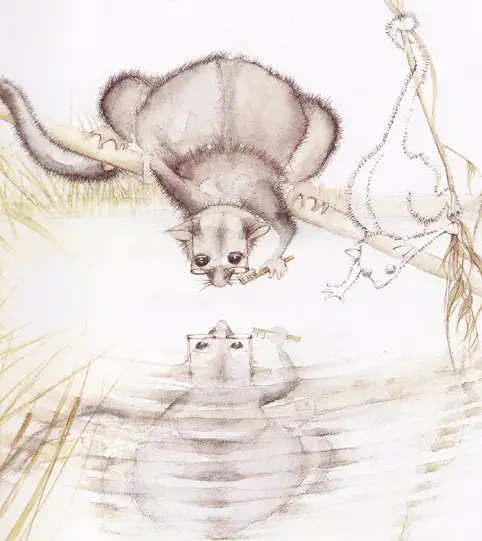

Mem Fox’s Possum Magic is a quest narrative, following an ancient tradition in which a hero strives for something of value such as treasure or a beautiful woman. In this storybook the quest is for personal identity, a universal, internalized, and significantly contemporary goal. Grandma Poss makes Hush invisible to keep her safe from snakes. Hush has lots of adventures but there comes a time when she wants to be visible again. Most pertinently Hush wants “to know what [she] looks like.” In Julie Vivas’s illustration Grandma Poss leans over a pool of water witha fuzzy outline of Hush beside her. But Hush has no reflection in the mirrored surface of the pool. Because she is invisible she lacks subjectivity and, therefore, agency.

The food in Possum Magic is obviously important, but did you know how important?

But Grandma Poss has trouble finding the magic to make Hush visible again and, although Hush tells her she doesn’t mind, “in her heart of hearts she did”. Eventually Grandma remembers that, “it’s something to do with food. People food—not possum food”. And she and Hush set off around Australia to find the food that will make Hush visible.

[…]

The foods that Grandma Poss and Hush eat are seen to be quintessentially Australian and their journey is a search for national and cultural identity as well as visibility or subjectivity. Fox’s narrative suggests that an individual’s sense of self does not arise spontaneously but is derived by literally consuming culture. By eating these significantly Australian foods Hush becomes visible and can be recognized as having a legitimate place within Australian society; she thus eats her way into culture. This reflects and supports the notion that ‘we are what we eat’ and that food narratives teach children how to be proper human subjects.

When we say this is an ‘Australian’ picturebook we should be careful to acknowledge that it represents a particular part of Australia and not its whole. She also offers a great example of the word ‘metonymically‘, which comes in handy when talking about picture books:

Applying a post-colonial reading to this storybook, which was published in the early 1980s, it is pertinent to point out, however, that the national and cultural identity Fox writes about is limited: geographically to the coastal regions of Australia and gastronomically to exclude indigenous foods and flavours.

In Fox’s narrative food is the magic that makes Hush visible. It constructs her as a subject and thus may be said to stand in, metonymically, for culture itself. For Michel Foucault culture is the magic that makes individuals visible. Following Nietzsche, Foucault argues that cultural discourses of truth, power, and knowledge distinguish between normal and deviant behaviour, thus determining individuals’ actions and constructing them as subjects. For Foucault power does not “crush” individuals; it does not need to because

[it is] one of the prime effects of power that certain bodies, certain gestures, certain discourses, certain desires, come to be identified and constituted as individuals… The individual is an effect of power, and at the same time, or precisely to the extent to which it is that effect, it is the element of its articulation. The individual which power has constituted is at the same time its vehicle.

In Fox’s story the consumption of certain foods constitutes Hush as an individual. The various foods might be said to carry certain discourses or stories about what it means to be Australian, including lifestyle, attitudes, desires, and even power relations (who gets the biggest slice?). As Hush consumes these foods, she also consumes Australian-ness and is constituted as an Australian. As a visibly legitimate Australian subject Hush embodies culture or as Foucault puts it, she is an “effect of power.” Simultaneously she is also “the element of its articulation.” Hence by her annually repeated consumption of proper Australian food/culture she confirms, for all those (child readers) now able to see her, just what it means to be Australian.

And the feminist reading:

Having eaten into Australian culture, Hush is visibly an individual. Grandma Poss is additionally visibly designated as specifically female by the apron she wears (notably she is the only character in the book who is clothed). Judith Butler argues that the body is “always ready a cultural sign” and is “never free of an imaginary construction” as either male or female. To Foucault’s argument that there is no position outside power/knowledge,” Butler adds there is no classification outside of the culturally assigned binary opposites male and female. For Butler embodying culture means acquiring the necessary skillls, “bodily gestures, movements, and styles of various kinds,” to “constitute the illusion of an abiding gendered self. Butler argues that the bdoy is a politically regulated cultural construct,” “a signifying practice within a cultural field of gender hierarchy and compulsory heterosexuality”. Gender is an “act” which is both “intentional” and “performative”. It is “a strategy of survival within compulsory systems” performed through a “stylized repetition of acts” under “duress”. For Butler then, gender is performed rather than possessed. Its performance must be reiterated repeatedly in order that the illusion appear natural. Each and every successful performance reiterates the systems of power relations that produce the illusions in the first place. Even something as simple as Grandma Poss’s apron reinforces the systems of power relations that produce the illusion of femininity. The apron is a symbol of domesticity, a stereotypical accoutrement of the maternal figure in children’s fiction. Grandma Poss’s apron is metonymic of culture; it defines her and serves to reiterate the definition of proper femininity.

I didn’t grow up in Australia, but live here as an adult, so I approach this particular picture book both as a foreigner and as an outsider.

WONDERFULNESS

Strong Sense Of Place

There are now a lot of Australian picture books which star local fauna. Many of them are fairly pedestrian, introducing the young reader to the names of the creatures and perhaps what they eat and their circadian rhythms, but this story is particularly well done because of the mixture of local fauna (beautifully anthropomorphised), Australian food (for humans), Australian geography and Australian dialect. Few Australian picture books manage to combine all of those things, and so Possum Magic has become for Australians like a celebration of Australia. Indeed, this is a book by an Australian, written for Australians, and there was a time when this in itself was something to be celebrated.

In the years that I’d been reading to Chloë I’d been shocked and dismayed by the very few Australian books available for Australian children so I determined to write a very Australian book.

Mem Fox

Not every member of the international audience appreciates the book’s content. I suspect this is a reflection on how many books are exported from America, compared to the very small proportion imported to America:

Another book we had to read for school and another weird one. It was included with our history lessons and we had to read it to coincide with Australia. A lot of new words included with foreign animals, that make it difficult to learn because there’s nothing telling us what the animal is, even though there are pictures. So for example, you have a page with lots of animals and words that talk about wombats, kookaburras, dingoes, emus, and bush magic. To a 5 yr old with no knowledge of these animals, it makes it very confusing. We had to stop and talk about each one, but still, it was hard for him to remember the difference. Our lesson includes a song about kookaburras that my son really likes, so now after we’ve learned the song, it’s easy to remember the word, but the book wasn’t as helpful in that. Still, if you’ve the time to explain all the stuff in the book, it gives somewhat of an idea of some of Australian animals. Not enough info to be helpful, although the pictures were nice.

CONSUMER REVIEW

The consumer above is describing, nay lamenting, that they as parent are required to have a dialogic reading experience with their own child.

The Wacky Plot Does Not Need Explaining

Perhaps one difference between writing for young children and writing for adults in general is that in picture books an author can present any number of strange and unlikely things, and the audience will accept it — not as fact, but as a part of the story. So it is with Possum Magic; of course you turn invisible with a potion, and of course the only way to make yourself visible again is to travel around the country eating typically Australian junk food. Anything is possible in a world where possums talk, and wear glasses and sneakers. Things do make sense within the world of the story (somewhat): ‘…which is why Grandma Poss had made her invisible in the first place’.

To extend this idea a little further, though it is true that young children will accept almost anything in a well-written story, this is precisely the reason we need to be careful about offering them stories with a modern ideology. When there is the symbolic annihilation of non-whites and female characters, and world-views which should have gone the way of the dodo, it’s not that the child reader doesn’t notice; it’s because these ideas are being so thoroughly taken on board that the ideas themselves seem invisible.

Language

Not every picturebook author can get away with this: Half rhyming, half not rhyming. But Mem Fox does:

Rhyming:

Grandma Poss made bush magic./She made wombats blue and/kookaburras pink.

She made dingoes smile and emus shrink.

Not rhyming:

But the best magic of all was

the magic that made Hush INVISIBLE.

How exactly does Fox get away with this combination? The rhyming accompanies the most magical parts of the story, for example when Grandma Poss is looking at her recipe books. When she’s not rhyming, she’s making use of some other technique, such as alliteration or repetition…

Again, this popular technique is employed here, with three sequences that begin with: Because she couldn’t be seen…’

NOTES ON THE ILLUSTRATION OF POSSUM MAGIC

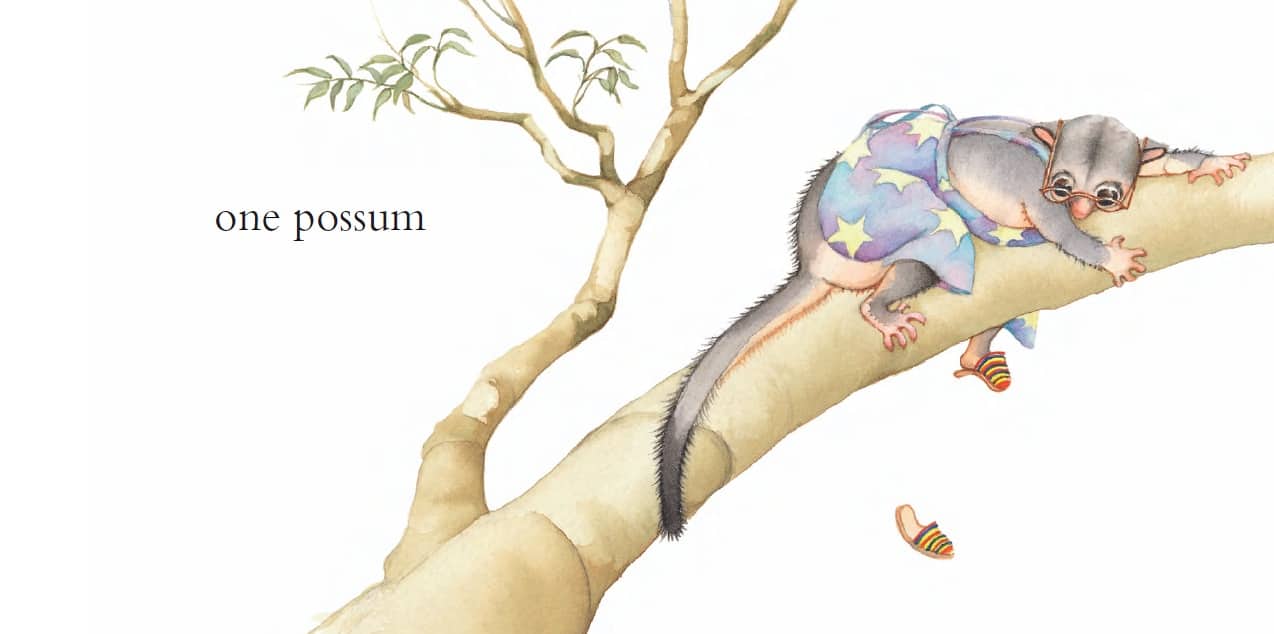

Julie Vivas is a master of watercolour. A lot of picturebooks have been illustrated with watercolour used as a kind of textured fill, but the watercolour line in this book is delicate and precise.

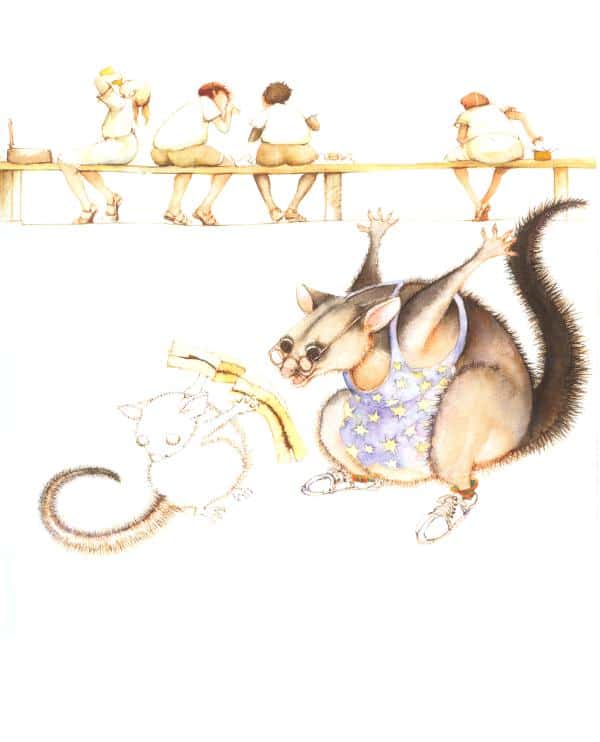

An artistic problem that Julie Vivas would have had to overcome is, ‘how to depict an animal that is invisible’? She deftly resolved this issue by painting a furry outline.

The white background allows the detail and texture of the paintings to shine.

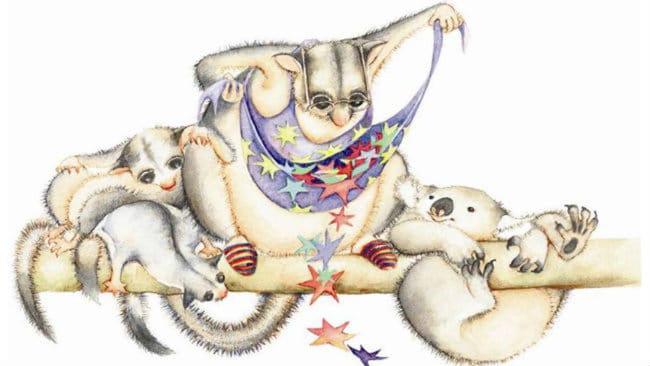

Below is the image from the front cover. The magic is represented by colourful stars.

One reviewer on Goodreads notes that Grandma Poss reminds him of Grandma Moses off the Beverly Hillbillies. I suppose Grandma Poss might be the picturebook version of the Cool Old Lady trope. Like Grandma Moses makes medicine in an old copper stiff, Grandma Poss uses bush magic to protect her grandchild from snakes. One distinctive thing about possums is their big, dark eyes. Vivas has made the most of this feature by giving Grandma Poss a pair of glasses. Notice how the characters have been drawn to be as endearing as possible. Even the names are endearing: Hush and Grandma Poss (shortened from possum, which is in itself a very Australian thing to do).

The character illustrations are full of life. Notice the children sitting on the form bench; they are not just sitting, but absolutely in motion, drinking a juice box, leaning forward, biting into lunch.

STORY SPECS OF POSSUM MAGIC

Between 30-32 pp, depending on the edition

Published 1983, this was Mem Fox’s first book. She famously didn’t find it easy to find a publisher, but we say that of any book that took off later, don’t we? Almost all books, no matter how classic they become, find it difficult to get a placement at a publishing house.

Older editions of Possum Magic feature a map of Australia with place names. I wonder why publishers have decided to take this out of earlier versions (or perhaps it is simply an Australian/International publication difference, in which case Australians wouldn’t necessarily need a map).

COMPARE POSSUM MAGIC WITH

Other Australian classics include Shy the Platypus and Wombat Stew.

Like Possum Magic, Wombat Stew is a popular musical for children. My daughter went to it on a class trip in kindergarten and loved it.

WRITE YOUR OWN

Perhaps you’re sufficiently familiar with a specific place/culture that you’re able to introduce a lesser-known animal or plant or custom or food to a young reader.

Possum Magic is a kind of faux-folktale, in that the story explains why Australians eat certain foods once per year on their birthdays. What other aspects of a young reader’s life could be ‘folklorised’ in similar fashion?