Gravity is a science fiction film from 2013, with a strong mythological, Christian influence.

Logline: A medical engineer and an astronaut work together to survive after an accident leaves them adrift in space.

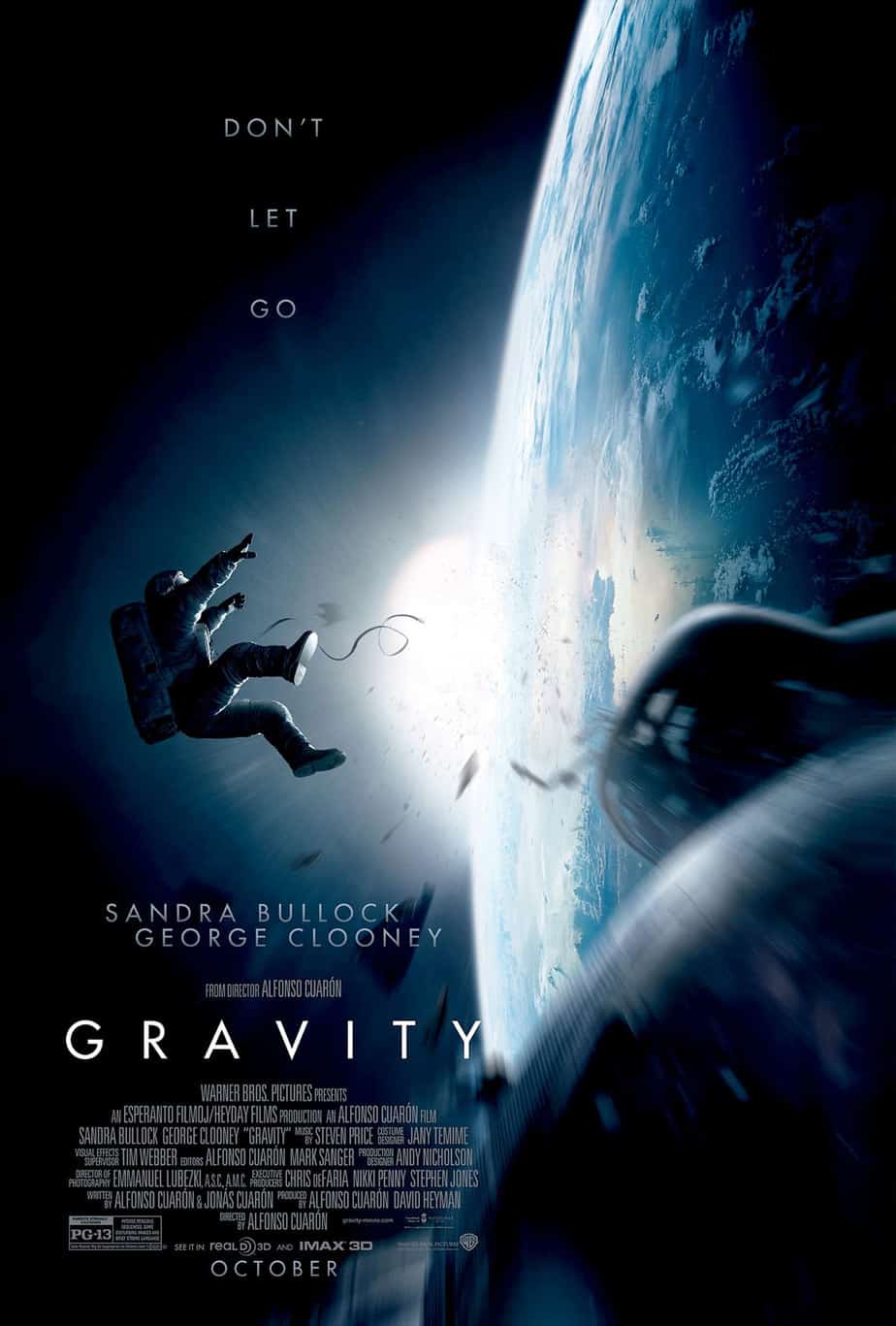

Tagline: (seen above) Don’t let go.

Arc word: ‘let go’. “You’ve got to learn to let go,” Matt tells Ryan. We’ve also got the visual motif of Ryan letting Matt go irretrievably into space.

Controlling Idea: A middle-aged space engineer learns to appreciate life again and believe in herself after a series of narrow escapes in space.

Theme Line: When you feel all alone and about to give up, fortify yourself by finding some imaginary person to give yourself some comfort.

Story World: Floating around in space

Symbol Web: ‘Tethered’ (grounded) versus being ‘untethered’ (lost and all alone, with nothing to hold onto).

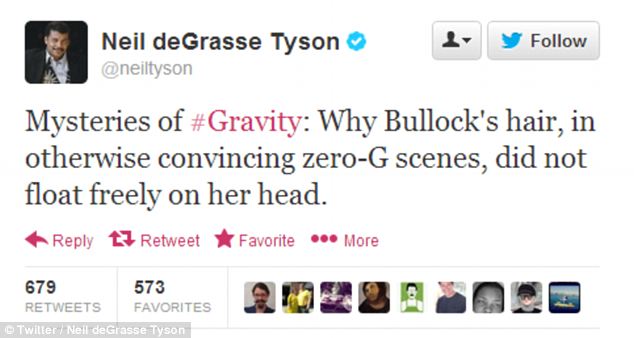

Mooshing The Science

See: Getting Science Right In Film: It’s Not The Facts, Folks

This is a good example of a SF story in which the writers hired a science advisor, then picked and chose which parts of actual science would help and which would hinder their storytelling. They ended up with a film which can really annoy scientifically literate fans of mimesis, but for viewers who are able to suspend disbelief, and who enjoy predictable plots, this is a well-crafted sci-fi thriller with a satisfying character arc.

The writers of Gravity seem to be following the advice to ‘dazzle the audience with pyrotechnics’ as a way of hiding the improbabilities, which Michael Hauge offers as one screenwriting technique in his article on how to create believable stories, but as he says himself, ‘This is definitely the last resort solution to the problem of credibility.’

On The Problem of Nature As Opponent

Every good story needs an opponent, but in disaster stories, the main opponent is a force of nature. The huge disadvantage of having nature as opponent in a story is that nature has no motive and no morality. Nature simply is. In a disaster story, several of the story steps are unavailable to you. The opponent doesn’t understand the hero’s greatest shortcoming. The hero and the opponent aren’t basically the same only with different moral codes. The opponent has no ‘plan’ and so the only ‘counterattack’ possible is an upscaling in the level of disaster. A chain of things will go wrong, starting with the initial disaster, and the hero will really be put through hell, emerging as a changed person. Sidekicks are likely to die along the way, but which ones? The only mystery is how.

Here’s what Howard Suber has to say about ‘nature as antagonist’:

When someone climbs a mountain, blazes a trail through a forest, uncovers a secret of nature, explores outer space or the oceans below, we may say the protagonist “big struggles” with nature, but it is not the same as a protagonist’s big struggle with a villain. Heroes and villains possess consciousness, will, and intention. Nature has none of these. […] The absence of good and evil in conflicts with nature poses a dramatic problem, because without this moral component, interest in the story becomes more difficult to sustain. This is why disaster films — which by definition deal with some conflict with nature — almost always have a second conflict, which involves other humans.

In Gravity there is no human opponent, which means the action and the setting are responsible for holding our attention.

But as one of the writers of Pixar’s Inside Out wrote about Nature As Opponent:

I came on Inside Out, Pete [Docter] was not leaning towards any villains. I think at one point there was the idea floated that those Forgetters are villainous in trying to grab the core memories so Riley would forget them. But it just never really caught Pete’s imagination and it really wasn’t what he wanted to focus on. And as a storyteller, I love that more complex idea. And so Pete Sohn [the director of The Good Dinosaur] decided very early that you’ll have characters that Arlo will come into conflict with and challenge him for sure. The villain is, if there is one, you want it to be nature. The movement of nature and the idea that nature is something to be respected—that was the antagonist of this movie.

So there are definitely writers who feel that you get a more complex story when the main antagonist is nature, since the most relatable villain is yourself, or nature.

Cartoonish and Cliché?

This is basically a myth-based disaster movie set in space.

What makes this plot cartoonish, and which cliche in particular is Ryan Stone?

Cartoonish aspects: One disaster thing after another, with debris flying everywhere. A cheap trick where the audience can’t believe a character has made it back, only to realise ‘it’s all a dream’.

Character cliché: While stranded and alone in outer space — a metaphorical extension of her miserable life on earth — our heroine learns to believe in herself.

Politics

There are also feminist issues with this film, but I’ll leave that for later.

The more you look at this film, the harder it is to believe anything other than ‘This is a super Christian film’. Honestly, I didn’t even notice it the first time. But here’s what John Paul The Great University has to say about it:

Consider a film whose main character goes from wanting to kill herself to praying for strength and faith within the span of five minutes. Consider a film that uses blatant imagery of a child living and breathing in the womb. Consider a film that preaches the triumph of faith and life over despair and death.

First, a look into the story’s structure.

Story Structure

The story opens very much like the start of Contact and various other space films. We hear a babble of talking and see Earth in the background. The inconsequential nature of the talking juxatposes against the magnitude of seeing our home from a distance; the chatter is insignificant and so is our earth. Something about country music as a soundtrack contributes to that uneasy juxtaposition between calm and high-stakes terror. When the music stops it’s replaced with SFX reminiscent of a heart beat, which is always a good way of upping blood pressure in the audience.

Anagnorisis, need, desire

In reality, two astronauts working together in space would at this point know rather a lot about each other. So the audience suspends disbelief when their characters exchange expository dialogue which is intended for the viewer to get to know the characters.

At the start of the story: Ryan is a novice space traveller – this is her first mission (to do we’re not sure what, exactly) after a six-month training period. She needs to learn that she has the fortitude to survive in space and troubleshoot on her own even when she’s feeling completely and utterly abandoned and alone.

She needs: to be put to the test before she knows that she can cope.

Ryan already knows: that she’s okay in general with a bit of loneliness. Matt asks her at the very beginning period of calm what she likes about being up here. She replies that she likes the silence. “I could get used to this.”

Ghost (backstory)

Dr Ryan Stone tells Matt on their slow journey back to the ISS that she had a daughter but the daughter slipped and hit her head while at school and died. There’s no husband. “Every morning I wake up, I just drive.” At this point in the story she is emotionally numb, doing high-level work but on autopilot. The nature of her daughter’s accident suggests that Ryan feels a dispiriting meaninglessness to life. Terrible things happen suddenly and for no reason. No point fighting fate.

The curse of gender is hinted at when Matt says that Ryan is a ridiculous name for a girl, who’d call their daughter ‘Ryan’? Ryan says that her father was hoping for a boy. Embedded in that particular ghost is that Ryan has got to where she is today as a space engineer by channelling her masculine side and that her (dead?) father expects a lot of bravery from her. (Can anyone think of a less sexist interpretation for that particular character detail?)

Setting

Space. Not so far from earth that you can’t see it. Earth looms large in the background. This is juxtaposed with the cramped environment of the shuttle.

Stories set in space have a lot of common with stories set on islands. Both of these settings are simultaneously highly abstract and completely natural. They are both places separated from humanity. Heroes placed in space and on islands often need to learn resilience and self-reliance.

Shortcoming & Need (Problem)

Ryan’s psychological shortcoming is that she can become paralyzed by fear.

Moral shortcoming: Her mission is to do her work in space and then to return home alive at all costs. That’s the morality behind this story; suicide is not a noble thing.

In order to have a better life: She needs to have a near-death experience so that she can fully appreciate being alive.

Ryan’s crisis at the beginning of the story: She’s going through the motions of life. She doesn’t feel fully alive, bereft and alone. (Very similar to Jodi Foster’s character, Ellie, in the film Contact.)

Inciting Incident

Ryan, Matt and another space engineer are on a space walk when they learn from Houston control that an explosion has just occurred at a Russian satellite. Now there is a storm of debris coming upon them at the STS. Soon they lose communication with the Mission Control in Houston. Debris strikes the Explorer, damaging it irreparably, leaving only Ryan and Matt alone in space. They no longer have incoming communication with Houston control.

This inciting incident will throw Ryan out of paralysis — passivity and reliance on Matt to buck up her spirits — and into action. She’ll need to save her own self.

Desire

Ryan wants to do her work on the STS-157 mission then return safely to earth.

Ally

Matt is the older, more experienced, ridiculously calm co-worker who realizes that new recruits need an environment of tranquility in order to function in space. He is calm to the point of actually being a bit negligent, joking around etc. But his demeanour is exactly what Ryan needs as a template as she contemplates death.

Opponent

Nature. The inhospitability of space. Once their ship has blown up Ryan and Matt are alone in outer space.

Changed desire and motive

Ryan wanted to do her work before returning to earth. Now she just wants to return to earth with both herself and Matt alive.

First revelation and decision

As they approach the slightly damaged ISS, they see that its crew has already evacuated in one of the Soyuz modules and that the parachute of the other Soyuz, designated TMA-14M, has accidentally deployed, making it useless for return to Earth.

Plan

Matt says that the Soyuz can still be used to travel to Tiangong, the nearby Chinese space station, to retrieve another module that can take them to Earth.

Opponent Strikes Back

All but out of air and maneuvering fuel for the thruster pack, Ryan and Matt try to grab onto the ISS as they zoom by it. But the tether holding them together breaks and at the last moment, Ryan’s leg becomes entangled in the Soyuz’s parachute lines. Ryan grabs Matt’s tether, just barely stopping him from flying off into space.

Matt realizes that his momentum will carry them both away, and over Stone’s protests, he decouples his end of the tether so that Stone can survive. The tension in the lines pulls her back towards the ISS.

Modified plan

As Matt floats away, he radios her with additional instructions about how to get to the Chinese space station, encouraging her to continue her survival mission.

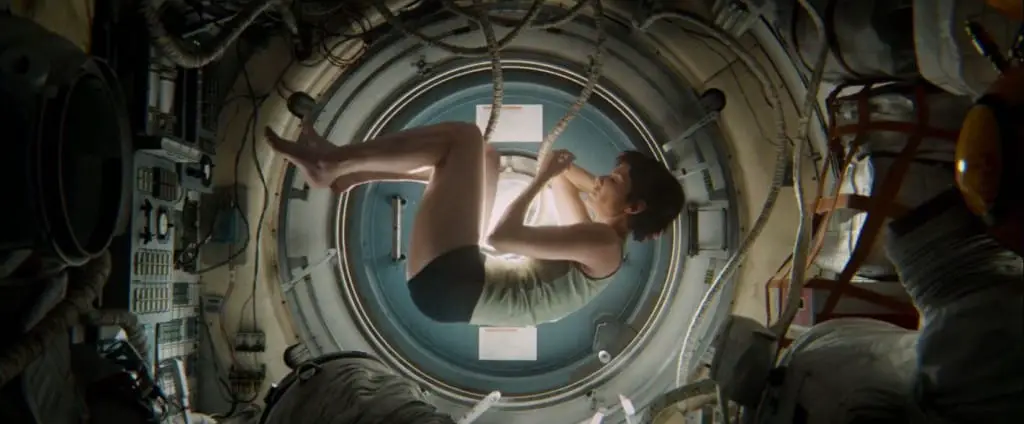

Ryan wants to get herself home alive at least. But her drive isn’t obsessive yet. We see her almost curl up into the foetal position upon entering the Russian station. Even the tubes in the background look like an umbilical cord.

Opponent Strikes Back

Ryan begins to get familiarized with the ISS when an alarm suddenly alerts her to a fire which has broken out due to the earlier damage.

Drive

Ryan is determined to put out the fire. She manages this by staying calm, reading from the manual and ejecting the part of the station that is in flames. She makes her way to the module where the fire is and attempts to put it out, but she is momentarily stunned when the force of the extinguisher thrusts her backward into the bulkhead. She recovers and knocks the flames down again and pushes through them towards the Soyuz. With the fire closing in, she closes the hatch, pulling in the fire extinguisher at the last moment when it blocks the hatch.

Gate, gauntlet, visit to death

Everything that can go wrong does go wrong: Ryan separates from the ISS only to find that the Soyuz’s parachute lines are entangled in the station’s rigging. She dons a Soviet spacesuit and exits the spacecraft to release the cables when the debris field completes its orbit. Clinging to the Soyuz, the ISS is destroyed around her. Free of the ISS and the parachute lines, Ryan reenters the spacecraft and aligns it with Tiangong. She fires the thrusters but the fuel gauge is wrong: the tanks are empty.

Apparent defeat/Attack by ally/Audience Anagnorisis

Though these are all separate steps in a story’s structure, this film is limited when it comes to varied backdrops, and both steps happen in the one scene.

Ryan realizes she is stranded and believes she’ll die. After listening to an Inuit fisherman on the ground speak to her, she slows the oxygen flow which will cause her to fall into unconsciousness from lack of oxygen before she dies. We realise she’s losing her mind when she starts howling like the dog in the background.

Alone in the cockpit of the Russian station, Ryan is at the point of giving up when Matt’s apparition appears suddenly. The imaginary Matt tells her that that curling up and dying in space is the easier option, because nothing worse can happen to you than losing your four year old daughter.

Listen, do you wanna go back, or do you wanna stay here? I get it. It’s nice up here. You can just shut down all the systems, turn out all the lights, and just close your eyes and tune out everyone. There’s nobody up here that can hurt you. It’s safe. I mean, what’s the point of going on? What’s the point of living? Your kid died. Doesn’t get any rougher than that. But still, it’s a matter of what you do now. If you decide to go, then you gotta just get on with it. Sit back, enjoy the ride. You gotta plant both your feet on the ground and start livin’ life. Hey, Ryan? It’s time to go home.

She reaches some random guy on earth and can hear a dog in the background. When she starts howling like a dog herself and talking about how she’s going to die “We’re all going to die, but I’m going to die today,” we know she’s given up.

The audience is fooled (or outraged at the lunacy?) at first, encouraged to believe that Matt has really made it to Ryan alive and in good spirits. But we quickly learn that he’s simply an hallucination.

Obsessive drive, changed drive, and motive

Ryan discovers the technique of constantly talking to herself, channeling Matt’s calm optimism, to assuage the loneliness of her situation and get herself home. The last real words we hear are a repeat of ‘arc words’ which we first heard in Matt’s dialogue with Houston from the first act: “I have a bad feeling about this mission…” (The final lines of another seemingly great female character likewise originate from her male sidekick in the psuedo-feminist film Contact.)

Realising that Matt is dead for realz Ryan wants to go to the Chinese station (Tiangong), which has been abandoned. But there’s no fuel in the Russian station so she can’t get there. However, ‘Matt’ has given her a hint: She’ll have to figure out how to get rid of most of the ship. At this point we see a definite change in the way Bullock is acting — she seems resolved and sturdy whereas before there was a lot of screaming and a bit of swearing, all the while looking bewildered.

Ryan ejects herself from the Soyuz via explosive decompression. She uses the remaining pressure in the fire extinguisher as a makeshift thruster to push herself the 100 mies towards Tiangong

She enters the Tiangong space station and makes her way through its interior to the Shenzhou capsule. The Tiangong station’s orbit has deteriorated due to hits by the debris field and it begins to break up on the upper edge of the atmosphere. Ryan is unable to separate the capsule from the space station.

Big Struggle

Which scene is ‘the big struggle scene’, when Ryan has been battling all along? I believe it must be the one right before the anagnorisis, where she’s strapped herself into her capsule and is hurtling towards earth.

Anagnorisis

Ryan seems to have some sort of spiritual epiphany and, whatever she believed before, now she believes in an afterlife. (There’s been a close up earlier on a Christian image of Jesus which is stuck to the controls on the Russian ship.)

Hey, Matt? Since I had to listen to endless hours of your storytelling this week, I need you to do me a favour. You’re gonna see a little girl with brown hair. Very messy, lots of knots. She doesn’t like to brush it. But that’s okay. Her name is Sarah. Can you please tell her that mama found her red shoe? She was so worried about that shoe, Matt. But it was just right under the bed. Give her a big hug and a big kiss from me and tell her that mama misses her. Tell her that she is my angel. And she makes me so proud. So, so proud. And you tell her that I’m not quitting. You tell her that I love her, Matt. You tell her that I love her so much. Can you do that for me? Roger that.I believe this is connected to her saying ‘Thank you’ in the final words of the film. Who is she thanking? That’s left up to the viewer.

Moral decision

Ryan has resigned herself to her fate, whatever it may be; she’d be landing on earth, but she didn’t know if she’d survive the impact. (Everything is in the hands of the Lord? Not sure.)

New Situation

In the final scene we see her standing on the edge of some unidentified lake, although the team in Houston has been tracking her and knows to come and rescue her. She’s back to earth alive, but this film truncates the new situation scenes. We will learn nothing more about this character than we already know – we don’t get to see her driving to work at the hospital, for instance, looking up into space and remembering her adventure.

Like in Contact, in the final scene of the film we see the hero clutching a handful of sand, though for slightly different reasons: This handful of sand signifies how glad she is to be back on earth.

She says ‘Thank you’ and laughs in relief. FADE TO BLACK.

If you’ve made it this far you can put up with a feminist perspective.

DOES THIS FILM ANNOY A FEMINIST?

There was quite a bit of feminist commentary on this film, partly because there are so few action films with female protagonists, and also — unusually — for the billing. This is from Aaron Ricciardi writing at Huffington:

Here’s why I’m livid: Gravity has a cast of two actors, Sandra Bullock and George Clooney. This is just a guess, but I’d say that Mr. Clooney is only on screen for about twenty minutes. Ms. Bullock, on the other hand, is never not on screen. She is the movie. So why, may I ask, does every piece of marketing material for a movie which pretty much features one actor and no one else for its entire ninety-minute running time look like this?:

SANDRA BULLOCK GEORGE CLOONEY

GRAVITY

Now, if the billing for Cast Away was laid out in the same way that Gravity‘s is, it would have looked like this:

TOM HANKS HELEN HUNT

CAST AWAY

Apart from the layout of the credits, I found other minor annoyances with this film.

1. The romantic banter between the Sandra Bullock character and the George Clooney character felt tacked on. If I were an X-Files shipper, I’d definitely be in the anti-romance camp. I don’t happen to think that every single story needs a romantic subplot, and this one certainly didn’t. The romantic subplot is that after George Clooney floats away, he asks Sandra Bullock to confess that she finds him attractive. Not much of a romance, admittedly, but it comes after flirtation and banter. The reason I’m disappointed in this is because women deserve to work in their chosen professions without necessarily being the object of banter from older male colleagues — in real life as in fiction. Likewise, women deserve to watch a scientist go about her work without that interference, even if it is George Clooney. Especially if it is George Clooney. Don’t the scriptwriters realise that had Bullock and Clooney remained professional with each other that this was the way to be cutting-edge? I’m sure that there are plenty of fans who like this in a storyline, but the problem is — for those of us who don’t — there is no reprieve.

2. In this story, with the experienced older man and the younger (though middle-aged) female engineer, the age and experience differential is supposed to justify the fact that all throughout the action, it’s Sandra Bullock who screams and panics, while the George Clooney character is affable, calm, collected and saves the woman to sacrifice his own life. IT COULD EASILY HAVE BEEN WRITTEN THE OTHER WAY AROUND.

…there was absolutely no reason for Clooney to sacrifice himself!!! Once Sandra caught him, he would be just floating there. A small tug on his tether would send him back to the space station. And as my wife put it, when you have a hold of George Clooney, only an idiot would let him go.

What Does A Real Astronaut Think Of Gravity?

3. There seems to be a rule and the rule is this: If a female stars on screen and she is good looking (when is she not, in Hollywood?) the audience must see what her body looks like. In this film both characters are dressed in shapeless moon suits. We only ever see Clooney’s face. But when Bullock returns to the safety of a spacecraft she removes her moon suit and there follows an extended scene in which she lies suspended in the room in partially fetal position. The audience just so happens to get many chances for the eyes to linger upon Bullock’s lithe musculature. One argument is that the disrobing is a part of the story. This is true. My question is: Do astronauts wear boy-leg underpants under their moon suits? I honestly don’t know. If roles had been reversed and George Clooney’s character was the one to make it back to the ship, would we have seen him in his underdaks? While Clooney and others have made their fame based on a certain amount of objectification, as has Bullock, I think an audience would have been surprised to find a male astronaut only wore underpants under a moon suit. I would expect a long-john type of garment, given the weather conditions of space. Therefore, the partial dress of the female character in Gravity feels gratuitous.

Also, how was Clooney going to beat Anatoly’s space walk record if astronauts apparently don’t wear either a diaper or a cooling garment under their spacesuits? That would be one smelly suit. Although I have to admit, that Sandra Bullock looked much sexier in her tank-top and boy shorts than I did when I took off my spacesuit.

What Does A Real Astronaut Think Of Gravity?

GENDER DIVERSITY

The Bechdel test sometimes needs a little modification, with commonsense applied depending on the film, and Gravity is no exception. In its most literal interpretation Gravity could never pass the test because there is only one female character and it is therefore impossible that two female characters exist who talk to each other.

However, there is a scene which violates the spirit of the Bechdel Test. I’m talking about the hallucination in which Clooney miraculously comes back to the cockpit to tell Bullock how to start a spaceship which is out of fuel. Clooney delivers an inspiring lecture just at the point where Bullock is about to give up. In fact, she has already lain down to die. Clooney’s character not only talks about technical aspects of driving the ship (his speciality and therefore appropriate to the story) but also gives Bullock’s character a personal life lesson which brooches the topic of her dead daughter.

I realise this is an hallucination scene, but in the context of fiction, it’s all made up, so I will ignore this point when I categorise this speech as ‘a man giving sage advice to a woman’. The ‘Fairy Godmother’ moment was delivered by a know-it-all man, even though ‘it didn’t really’.

And as I noted above, the final lines of speech — which are always the most resonant and important due to their positioning — were actually dialogue repeated from the male character.

If you’ve been looking forward to the rare Hollywood film in which an intelligent woman gets to save the day, you may be disappointed.

Update: I notice Cheryl Klein of The Narrative Breakdown was possibly even more annoyed than I was about the sexism in this film. I don’t think I’ll bother buying it for my six year old daughter after all, even though she loves space settings in stories. Still waiting for a riveting space story with good female characters. Still.

FURTHER READING